The NYMEX May 2006 crude futures contract closed today above $71.

The explanation that one sees in the popular press often runs along the lines of this report from Bloomberg:

Crude oil traded near a record set earlier today amid concern tension over Iran’s nuclear research will erupt into armed conflict and cut exports from the world’s fourth-largest producer.

“The political tension over Iran is what has kept the market high, and the president seems to want to rub it in as much as possible,” said Bruce Evers, an analyst at Investec Securities in London. “We may see $70 remain through the end of the month. The situation doesn’t seem to be getting any closer to resolution.”

|

I’ve previously expressed some doubts as to whether worries about Iran are the only factor. For starters, it cannot be irrelevant that U.S. crude oil production in January was half a million barrels per day lower than it had been last summer. At last report, 340,000 barrels of oil production per day remained shut in as a result of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. And as noted by the Oil Drum, Energy Secretary Samuel Bodman testified before Congress last month that many damaged Gulf oil rigs are never going to be repaired. According to Reuters:

“By and large those production platforms that are out are not going to be put back because it’s not economically desirable to reinvest to put those facilities back in place,” Bodman told the House Energy and Commerce Committee during a hearing on the Energy Department’s proposed 2007 budget.

Bodman said the shut-in production platforms are mostly in old oil and gas fields close to shore.

“They tend to be depleted and it would not economically be viable to reinvest in to rebuild them and the companies haven’t done that,” he said.

Even if U.S. demand for oil were stagnant, the lost production would mean that much more oil the U.S. needs to buy on world markets. And we’re not going to get it from Nigeria, where the International Energy Agency reports that 470,000 barrels per day were shut in during late February as a result of ongoing turmoil in that country.

|

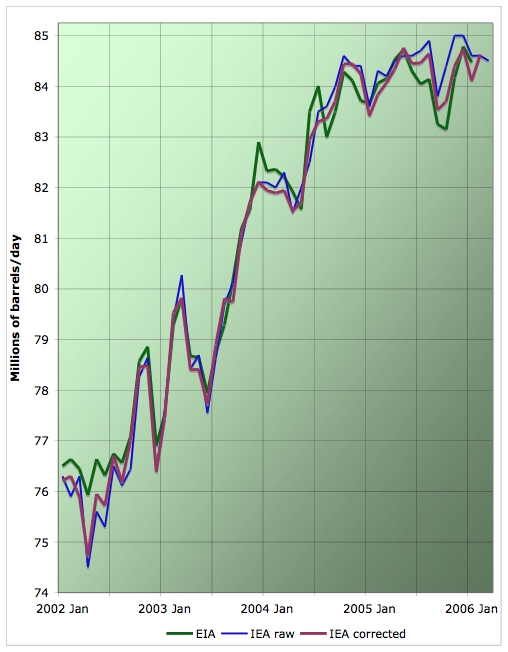

So far, production gains elsewhere have been insufficient to take up the slack. The graph above, taken from the Oil Drum, suggests that whether you use the figures from EIA or IEA, global petroleum production has yet to get back to the peak reached last year.

And demand remains strong, with U.S. economic growth resuming at a faster pace than some of us had anticipated, and Chinese use of petroleum continuing to climb. If demand is up and supply is stagnant, small wonder if we see the price continue to rise.

A more boring story, perhaps, than that reported elsewhere. But that doesn’t mean it’s not true.

Technorati Tags: oil prices,

oil, Iran

The problem I see with a straighforward supply-shortage explanation is that crude oil stockpiles are at multi-year highs:

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=10000100&sid=acy5toMILYyw&refer=germany

“April 13 (Bloomberg) — Crude oil fell in New York as U.S. inventories at an eight-year high eased concern of potential shortages because of threats to supply from Iran and Nigeria.

“Oil declined yesterday after the Energy Department said U.S. stockpiles gained 0.9 percent to 346 million barrels last week, the highest since May 1998. Prices also fell after failing to close above their high this year of $69.20, reached on Jan. 23, analyst Dariusz Kowalczyk said.”

That day oil fell to $68.62, not too far from current levels.

If these high prices are due to supply shortages, why are stockpiles at these multi-year high levels? One would normally expect to see stores being drawn down during a shortage. This is why analysts are looking more to anticipated future shortages, I think.

Here’s an explanation that ties together both of these perspectives:

The “excess” build-up of inventory is due not to a matching increase in actual consumption, but rather is a play on oil contango.

That is, market participants are anticipating higher crude prices in the future, so they are buying at today’s lower prices (that is, buying more than usual), storing the excess, and planning to sell the crude in the future at higher prices. In fact, they probably have futures contracts locked in to do this.

This would result in present-time prices for crude being “time-arbitraged” higher than usual, and storage build-ups resulting as the arbitraged oil awaits sale.

The original contango’d structure of the crude futures market could be attributed to both worries about more conflict with Iran (or in Nigeria, Iraq, or Chad), as well as a heavy summer consumption season.

Ooops… the first sentence in the above post should read something like “due not to a matching increase in production or decrease in consumption”.

Note that 1998 oil consumption was ~18 Mbpd:

http://powerlab.fsb.hr/OsnoveEnergetike/1999/bpstat/tables/oilcon2.htm

Today, U.S. oil consumption is ~21 Mbpd, or 17% higher.

Thus, the U.S. stockpiles of 346M is proportionately less. Stockpiles may be the same as 1998 in absolute terms, but they are smaller relative to higher demand.

The contango might be due to a sort of bottleneck or

“cobweb effect” in the oil futures market. Yesterday’s WSJ indicates that a lot of investors (maybe “indirect speculators” is a better term) have put money into the oil futures market in a small amount of time. These principals presumably aren’t very price-sensitive on a day-to-day basis, and their agents have a mandate to put money into oil futures.

Oil settles at over $70 per barrel

Crude oil closed above $70 a barrel yesterday for the first time despite the fact that U.S. oil inventories are at their highest levels in nearly eight years. Thus, this current price spike appears to be a reflection of a…

“Oil goes higher and higher”

Econbrowser takes a look at the underlying causes for the recent increase in oil prices.

…

A lot of people interpret inventories as Hal is suggesting, and it makes a good deal of sense. I’ve never been entirely comfortable with this way of thinking, however.

Suppose you are a seller of oil (or just a speculator looking for a profit opportunity), and there is a shortfall of supply. Do you respond by selling out of inventory or by raising prices? If you thought the shortfall was strictly temporary, then I agree you would run down your inventories. But if you thought that the situation was going to be even worse in the future, you might respond by raising prices so much that inventories accumulated. For this reason, my view is that an increase in inventories sometimes signals that demand is weak relative to current production, but need not always be indicating this.

I agree that there must be some forward-looking or speculative element of the current situation, though this could in part be an assessment that U.S. and Nigerian production are not coming back up in the near future, while demand will continue to grow. And I do not mean to be claiming that Iran fears are playing no role– surely they are. I’m only suggesting that other factors besides Iran should not be overlooked.

Is there any relationship between the falling dollar and rising crude oil prices? If the dollar falls, shouldn’t it take more dollars to buy crude? After all, it seems the Fed favors a policy of firing up the printing presses:

http://www.federalreserve.gov/boardDocs/speeches/2002/20021121/default.htm

The price of copper is a great leading indicator of the price of oil — for the last 20 years the price of crude this month has about a 0.93 correlation with the price of copper in the prior month. Both prices are generally a signal that world economic growth and demand is very strong.

Moreover, the inventory situation in oil may be similar to the situation for copper stocks at the London Metals Exchange. Falling LME copper stocks generally lead falling copper prices. But over the last couple of months copper stocks at the LME have started to build while copper prices have continued to rise.

Something worth watching.

One point with regard to the production graph from theoildrum.com. It is important to remember that to close order, production equals consumption; so this can also be interpreted as a consumption graph. When you say, “global petroleum production has yet to get back to the peak reached last year”, you could also say, “global petroleum CONSUMPTION has yet to get back to the peak reached last year”.

The fact that we see a plateau in both production and consumption does not tell us that we have a supply/demand imbalance. Now you might say that, in conjunction with record high oil prices, it does in fact have that implication. But really, you don’t need to know that production and consumption have leveled off to draw that conclusion. It is really the high prices which provide evidence of a supply shortage relative to demand.

Even if both production and consumption had been climbing in the past year, if we had the same price history as we have seen, we would still have evidence for production shortages. We would just say that, although supply had risen, it had not risen as much as demand, hence the high prices.

So I don’t particularly see that the production/consumption stagnation in the past year is evidence for shortages in and of itself. It is the high prices that make the case. Given high prices, if production & consumption had both been falling in the past year, we’d say we had supply shortages; if they were level we’d say we had supply shortages; and if they were climbing we’d say we had supply shortages. The production/consumption history is an ambiguous piece of evidence that could be consistent with almost any story.

The NT Times has a good story by David Sanger (“China’s Oil Needs Are High on U.S. Agenda”). It has the typical scary graphic (extending yours at the same slope out to 2030[!] of China’s projected oil consumtpion (from the Energy Intelligence Group, whoever they are). And he quotes some of the Bushes accusing China of “mercantilism” in trying to sewing up political relationships with oil producers. (They should talk!)

BUT, not to worry: Sanger quotes a bunch of experts outside the Bush Administration who think that “the competition can be overblown.”

“I sense that there is a diversity of views on this among the Chinese I speak to, and there are some who are questioning this mercantilist policy,” said Elizabeth C. Economy, of the Council on Foreign Relations, and the author of “The River Runs Black,” a study of the environmental impact of China’s growth.

“If China has a prayer of continuing to grow at this rate, they have to move to far more efficient ways of using energy,” she said, making a point that President Bush has made repeatedly in recent weeks.”

“Bates Gill, a China scholar at the Center for Strategic and International Studies here, warned recently that the United States had “thus far tended to over-exaggerate this issue of energy in our ever desperate search to find yet another major competitor with which to pick a fight.”

That sounds about right to me.

(http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/19/world/asia/19china.html

I work in project controls in the EPC (engineering,procurement, & construction) side of the petro/chem industry. The industry here in Houston is running flat out. Lead times for equipment have grown. The Chinese have already driven up the prices of stainless and inconel among many other plant commodities. Engineering firms are short personnel and those that stay hop scotch from one firm to the other for more money.

Our HR guy says he needs 50 engineers and he can’t find them and we are a smaller player.

The oil companies that lost rigs/platforms in the shallow parts of the Gulf will spend hundreds of millions to demo and retrieve what the can from the topsides. Day rates for services in the Gulf have gone up because of demand. Shell, Chevron and the others are competing for the same limited offshore services.

Well, I guess we don’t have to worry about the increasing-supply paradox anymore:

Oil prices rise to new record above $72 US a barrel as gasoline supply shrinks

That didn’t last long.

A question for Professor Hamilton,

Could another factor be the devaluation of the US dollar?

Please, look at the price of gold and silver these days.

Thanks

Marconi, yes, in principle depreciation of the dollar could certainly be a factor. But the dollar is only down about 4% against the Euro over the last two months, so I think this could explain only a minor part of the rise in the dollar price of oil.

And if the argument is based on fears of future dollar depreciation, there are other more straightforward ways to profit from this (e.g., buy Euros forward)– such fears would show up dramatically elsewhere.

You certainly also make an excellent point about gold, which I’ve also discussed here and here.

I remember a time before oil futures markets made all of these interesting possibilites possible. Until the 1970s, the price of oil was stable, and production was controlled largely by the big American and European oil companies.

The 1970s threw this tidy oligarchic world into confusion. The Arab oil embargo in 1973 signaled the rise of OPEC. (I remember standing in gasoline lines, due to misallocation of supplies by the companies!)

For producers and users of oil, price volatility became serious problems. They needed a way to hedge the voltatility in Short term physical markets. A group of energy and futures companies founded the IPE in 1980 and launched the first futures contract, on Gas Oil, the following year. In June 1988, the IPE launched Brent Crude futures.

I dare say that if we were still doing it the old fashioned way, we might have blundered into a war in the Middle East over access to oil–Oh, wait … Never Mind! The Wikipedia entry on the IPE:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Petroleum_Exchange

What does today’s price really tell us? A few months ago, oil was selling for $56/barrel. Has the supply or demand situation really changed in one or two months to justify the price increase on fundamental economic supply/demand analysis of the physical market ? I don’t think so.

In one month, copper climbed from $2.12 to $3.00 while the physical market stabilized and went into surplus. Ditto aluminum.

I think the price discovery mechanism is broken. Certainly the case can be made that the resource sectors of the world are in need of capital and that moderate price increases can be justified. But the current acceleration and subsequent decelerations are artifacts of a speculative frenzy driven by execess liquidity and organized price fixing in the financial arena.

The futures market, in it’s current state, is not an efficient price discovery mechanism. It is a vehicle for big money to dominate short run pricing, at it’s whim.

I can’t tell where the price of commodities should be. The rolling bubbles in the world economy, the massive printing of money by the world’s central banks, the short term impacts of the Republican spending spree, and the mass industrial build out of the offshore factories, have distorted the short run economic landscape beyond analysis.

$75.13 bbl on Friday. Jumped $1.48 in one day.

Join the resistance!!!!

I hear we are going to hit close to $4.00 a gallon by next summer and it might go higher!! Want gasoline prices to come down? We need to take some intelligent, united action. Phillip Hollsworth offered this good idea.

This makes MUCH MORE SENSE than the “don’t buy gas on a certain day” campaign that was going around last April or May! The oil companies just laughed at that because they knew we wouldn’t continue to “hurt” ourselves by refusing to buy gas. It was more of an inconvenience to us than it was a problem for them.

BUT, whoever thought of this idea, has come up with a plan that can really work. Please read on and join with us! By now you’re probably thinking gasoline priced at about $1.50 is super cheap. Me too! It is currently $2.79 for regular unleaded in my town. Now that the oil companies and the OPEC nations have conditioned us to think that the cost of a gallon of gas is CHEAP at $1.50 – $1.75, we need to take aggressive action to teach them that BUYERS control the

marketplace….. not sellers. With the price of gasoline going up more each day, we consumers need to take action. The only way we are going to see the price of gas come down is if we hit someone in the pocketbook by not purchasing their gas! And, we can do that WITHOUT hurting ourselves. How? Since we all rely on our cars, we can’t just stop buying gas. But we CAN have an impact on gas prices if we all act together to force a price war.

Here’s the idea:

For the rest of this year, DON’T purchase ANY gasoline from the two biggest companies EXXON/MOBIL and Chevron. If they are not selling any gas, they will be inclined to reduce their prices. If they reduce their prices, the other companies will have to follow suit.

But to have an impact, we need to reach literally millions of Exxon/Mobil and Chevron gas buyers. It’s really simple to do! Now, don’t wimp out at this point…. keep reading and I’ll explain how simple it is to reach millions of people.

I am sending this note to 30 people. If each of us sends it to at least ten more (30 x 10 =3D 300) … and those 300 send it to at least ten more (300 x 10 =3D 3,000)…and so on, by the time the message reaches the sixth group of people, we will have reached over THREE MILLION consumers. If those three million get excited and pass this on to ten friends each, then 30 million people will have been contacted! If it goes one level further, you guessed it….. THREE

>>>>HUNDRED MILLION >>>>PEOPLE!!!

Again, all you have to do is send this to 10 people. That’s all. (If you don’t understand how we can reach 300 million and all you have to do is send this to 10 people…. Well, let’s face it, you just aren’t a mathematician. But I am, so trust me on this one.)

How long would all that take? If each of us sends this e-mail out to ten more people within one day of receipt, all 300 MILLION people could conceivably be contacted within the next 8 days!!!

I’ll bet you didn’t think you and I had that much potential, did you?

Acting together we can make a difference. If this makes sense to you, please pass this message on. I suggest that we not buy from EXXON/MOBIL or CHEVRON UNTIL THEY LOWER THEIR PRICES TO THE $1.30 RANGE AND KEEP THEM DOWN.

THIS CAN REALLY WORK.

How about this radical line of economics: over the past two years the price of oil has risen from approximately $45 per barrel to $75 per barrel and production has risen from 83-84 mbl/day to 84-85 mbl/day.

Isn’t there information in the lack of a supply response to higher prices?

My own expectation (Hubbert stuff) is that global oil production won’t rise over 90 mbl/day anytime in the next five years regardless of price. Just consider the Saudis, for one example. Their official, optimistic production schedule calls for investing $50 billion over the next 2-4 years to increase production from 10.5 mbl/day to 12.5 mbl/day by 2009 . . . . . but global economic growth is producing a “natural” increase in oil demand of 1-2 mbl/year, so the Saudi projects at best will only satisfy about half of demand growth through 2009. And if you believe that the Ghawar field may peak, the Saudi’s may need 2 mbl/day of incremental new production just to keep NET production flat at 10.5 mbl/day.

Anyway, the immediate problem this summer isn’t oil or Iran, it’s gasoline. Shortages have already begun on the east coast and driving season isn’t underway yet (and to my untrained economic mind, shortages mean the price of gasoline hasn’t gone up nearly enough yet). My best guess for this summer would be a peak gasoline price at the pump between $5 and $10 per gallon, based on development of a classic “commodity price spike” sparked by the combination of a real short supply of gasoline as the driving season kicks in, widespread outages initially caused by a reluctance of megaproducers to raise prices fast enough to “clear” the market and hoarding by consumers panicked by the outages who start topping off their tanks.

My sources tell me the largest single pool of inventory (with flexible untapped storage) in the gasoline market is in the on average half full tanks of millions of vehicles on the road.

Anyway, stay tuned. Should be a wild summer. Might as well start blaming Bush now.

My admittedly sophomoric understanding of global oil investment is poignantly pragmatic, you know, lacking the usual nuanced understanding of the pros.

But here goes.

Somehow, oil went into contango, probably around November 2004. Since then investment in long oil has gradually risen and has now greatly spiked; investors are essentially transferring oil that usually resides in the ground to above ground storage. Refining in the US has been limping along since the natural disasters in the gulf and oil not refined has been stored.

If it pays more for investors to store oil, that’s what the investors are doing. Demand to pump oil out of the ground, to simply store it, is contributing to the high demand of oil. Oil not being refined (because it is being stored) is adding to the rapid rise in the gasoline price.

Oil investing has become a feeding frenzy, I think similar to the irrational exuberance of the tech crazy years. Are we looking forward to a dramatic downward correction?

I seem to agree with the fellow who concluded investment mechanisms are being used to game the system. When oil storage tanks are completely full and no storage space is available then what? Do we build more above ground oil storage to contain every drop the fields can produce, or do we simply start shipping oil into orbit, allowing oil to float about in wonderful amorphous shapes of it’s own physical properties. Long oil futures would just flip out then, to the tune of $10,000 pound.