What is the significance of the fact that the most recently issued subprime mortgages are the ones that are running into the biggest problems?

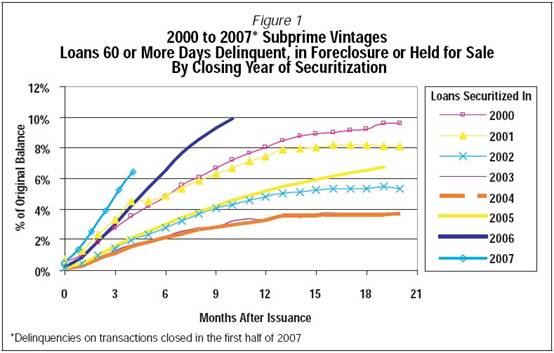

The following graph from Calculated Risk plots subprime delinquency rates (reported as percent of original security balance) as a function of number of months since issuance. The graph shows that the more recently the loans were securitized, the faster they have run into problems, with 2006 loans getting into a higher delinquency rate within 9 months of issue than previous vintages had after two years. Loans securitized in 2007 have been running into trouble even more quickly.

|

|

What is different about the most recently issued loans? For one thing, the borrowers are more likely to have experienced a capital loss, since they bought closer to the peak in house prices. If that’s the factor, it’s a fairly ominous trend, since it’s well within the realm of possibility that we are going to see much bigger drops in real estate prices than have been observed so far.

Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke commented on this trend Monday, and offered this explanation:

The rate of serious delinquencies has risen notably for subprime mortgages with adjustable rates, reaching nearly 16 percent in August, roughly triple the recent low in mid-2005. Subprime mortgages originated in late 2005 and 2006 have performed especially poorly, in part because of a deterioration in underwriting standards. Moreover, many recent-vintage subprime loans will experience their first interest-rate resets in coming quarters. With the softness in house prices likely to make refinancing more difficult, delinquencies on these mortgages are expected to rise further.

That the rising delinquency rates are due to weaker underwriting standards was also the conclusion of the analysts at Moody’s:

The data show that, as we have noted in previous communications, loan performance for the 2006 subprime vintage seems to be driven primarily by the proportions of stated documentation loans and high CLTV loans backing the transactions as well as the proportion of loans that combine (or “layer”) these risk characteristics. (Stated documentation loans are those loans for which the borrower’s income and assets are not verified by documentation during the loan approval process and therefore are more likely to be overstated.)

That’s also the conclusion of the analysis by Fitch, to which CR reader Bacon Dreamz calls our attention.

|

But that invites the natural question, why did underwriting standards deteriorate? Another important trend of the last few years has been a big increase in the share of securitized loans issued by the private sector rather than the government-sponsored enterprises.

|

Here again is the Fed Chair’s perspective:

At one time, most mortgages were originated by depository institutions and held on their balance sheets. Today, however, mortgages are often bundled together into mortgage-backed securities or structured credit products, rated by credit rating agencies, and then sold to investors. As mortgage losses have mounted, investors have questioned the reliability of the credit ratings, especially those of structured products. Since many investors had not performed independent evaluations of these often-complex instruments [emphasis added], the loss of confidence in the credit ratings led to a sharp decline in the willingness of investors to purchase these products. Liquidity dried up, prices fell, and spreads widened. Since July, few securities backed by subprime mortgages have been issued.

It is interesting to compare that description with the one that Bernanke offered last April:

[M]ost small retail investors are ill-equipped to provide effective market discipline because monitoring complex financial activities demands considerable time, effort, and sophistication. In the case of hedge funds, securities laws effectively allow only institutions and high-wealth individuals to invest in them. These investors generally have the resources and sophistication, as well as the incentive, to monitor the activities of the hedge funds. Large investors are not only well equipped to assess the management, strategies, performance, risk-management practices, and fee structures of individual hedge funds but they also have the clout to demand the information they need to make their evaluations….

Thus far, the market-based approach to the regulation of hedge funds seems to have worked well, although many improvements can still be made (Bernanke, 2006). In particular, risk-management techniques have become considerably more sophisticated and comprehensive over the past decade. To be clear, market discipline does not prevent hedge funds from taking risks, suffering losses, or even failing–nor should it. If hedge funds did not take risks, their social benefits–the provision of market liquidity, improved risk-sharing, and support for financial and economic innovation, among others–would largely disappear.

So here’s my question– why did the “most sophisticated” investors apparently become less and less sophisticated as time went on?

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

housing,

fed funds,

Federal Reserve,

economics,

subprime,

Bernanke

“why did the “most sophisticated” investors apparently become less and less sophisticated as time went on?”

I guess it depends on how one defines “sophisticated.” I had a friend in college who hated that term because immediately thought of the sophists in ancient greece peddling falsehoods (personally, I think the sophists got a bad name–namely because Plato and Aristotle got to write much of the history).

Our sophisticated investors may be sophists.

As housing prices shot up, affording a house became an increasing stretch (particlarly as the interest rates were no longer dropping). So the sophist-sophisticated market responded, loosening standards, rather than responding to the public: “this house is too expensive for you to purchase.”

A lot of those charts (loan-to-value, debt-to-income) seem to indicate housing values rising above previous affordability levels, and the market therefore stretching to paper over this gap.

So in summary, there may be a plethora of sophisticated sophist problem loans that have to be cleaned up as prices drop, this will exacerbate price drops, but there may be a floor that firms up as the more solid loans predominate (those issued prior to 2004, for example).

Maybe my friend was right. Perhaps the sophisticated are sophists.

And maybe it’s that the investors, many of them hedge funds, were chasing yield. According to Satyajit Das, “Defaulting middle-class U.S. homeowners are blamed, but they are merely a pawn in the game…. Those loans were invented so that hedge funds would have high-yield debt to buy.”

http://articles.moneycentral.msn.com/Investing/SuperModels/AreWeHeadedForAnEpicBearMarket.aspx?page=1

I think he’s right. I was on the buy-side at the time and (together with all the other old-timers) found it hard to believe the quite obvious risks buyers were willing to take for another .01 bp.

Try this hypothesis:

Institutions and mechanisms were being created to expand home ownership via easier and cheaper credit. That worked well for a while but changing conditions (higher housing prices and rising interest rates) should have applied the brakes.

However, institutions try to continue to expand and resist extinction. While conditions changes, inertia in owner and buyer expectations (continual appreciation of prices) and in institutional survivial instincts (those new mortgage shops on every street corner) overshot the market.

In engineering terms, we’ve had a bang-bang control with a large deadband. On the other hand, a properly functional financial system is a well-tuned PID controller. (“PID” = proportional-integral-derivative. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PID_controller)

Professor,

The simple answer is that greed often overrides rationality. When it comes to the markets, why is that surprising?

Because this (from the NYT) is the current fashion:

In short, hedge fund managers thought that the sophistication of data crunching technology meant that it was possible to get good results using econometric analysis alone. What they got for their efforts was one big lesson in the fact that in order for data analysis to be valuable it must be founded on solid theory.

I was wondering if a couple standards have been tightened in 2006 – 2007. Two questions at the end.

In the earlier days of this bubble we had the house flippers. That seems to have died maybe back in 2005 when price escalation slowed or stopped. I have read where SOME of those folks got Pay-Option Interest-only Negative-amortization ARMS and because missing the first few payments did NOT put the loan in default they could make it almost a year avoiding foreclosure with few or no payments. Then they sold. profited and paid off everyone.

Others simply couldn’t afford payments or as the rate adjusted then they couldn’t afford the payments. Then as the market price rose under them they refinanced, paid off the old loan and started again.

I think Pay-option Interest-only Negative Amortization masked many defaults.

So… my questions

1. How prevalent are the Pay-option, negative amortization loans in recent periods compared with prior periods? If those lenient terms went away recently it would seem to unmask some defaulters.

2. How many of the late 2006 and early 2007 defaulting loans are refinancings of prior deadbeats? Perhaps we are seeing mortgage companies trying to save their butts by figuring out creative ways to keep the game going so they don’t get caught as the BKs they truly are.

What I see when I look at the first graph is that 2000 and 2001 were pretty bad, and then 2002 got better, and then 2003 and 2004 were significantly better. It is reasonable to think that investors looking at those results might believe that those packaging these products had ‘fixed’ whatever was wrong with their methodology in 2000 and 2001. 2005 started off like 2002, though recently it has performed worse, and it wasn’t until 2006 that the performance started as bad as 2000 and 2001. Now 2006 is performing worse than 2000/2001, and 2007 has started off as the worst of the bunch. But that graph does not tell a story of steadily decreasing performance over time.

I agree with SotT’s conclusion — that the substitution of econometrics for reason accounted for the “unsophistication” of investors. I’ve argued as much on this blog’s forum for the past year or so. The question why market participants put so much stake in econometrics modeling. The answer, IMO, has to parts:

1) There was a general attempt to raise investing to the level of “science”, which coincided with the economics profession’s attempt to do the same with their discipline. The mantra was, “if you can’t model it don’t say it, and if you can model it, believe it.”

2) The models were good marketing tools for hedge funds and even pension funds (we know what we’re doing, because the people we give money to are disciplined). Some knew the models would go wrong and didn’t care (hedge funds have perverse incentives), and some fell for them completely.

The reason is it takes guts to be a Robert Shiller, or a Calculated Risk, two of the preciously few people who saw this coming and dared speak about it. I note that our esteemed blog host, presmuably a sophisticated observer, did not either.

There\’s a lot of Monday-morning quarterbacking going on, but precious few were out there when it mattered.

JDH, dare you step up to the plate and comment on where we\\\’ll be couple years from now?

Repastin JDH’s BB quote from last April:

If hedge funds did not take risks, their social benefits–the provision of market liquidity, improved risk-sharing, and support for financial and economic innovation, among others–would largely disappear.

Now people, wipe those cheshire cat smiles off yo face and suspend all that ‘2 and 20’ fee structure from yo cynical minds and concentrate on that:

their social benefits–the provision of market liquidity, improved risk-sharing, and support for financial and economic innovation, among others

and why any regulation might impair those great benefits.

Would you say that the current “liquidity crisis” is an example of this “improved risk-sharing”, or was the ususal tag, “disintermediation of risk”, a little torn to shreds –that this was a conglomeration of recklessness? We don’t need any more “financial support and economic innovation” like this.

We don’t.

As an originator my only incentive is to originate the loan ( fund the borrower and off load the asset off my balance sheet). I make my money on every loan originated. The quality of the borrower over the life of the loan does not interest me. That is airbrushed by the credit rating agencies for the repackaging houses on wall st. And the investor is handed a nicely packaged cookie tin, so that his fiduciary responsibility is met.

I dont think anybody was naive or ignorant in the process. The money ‘was/is/will be’ in the skim.

I think it was less about the first packaging and more about the second packaging of these loans into CDOs.

This is what seems obvious to me. There is actually some benefit to the ability of banks to be able to sell loans to investors willing to take risks. It means that banks aren’t necessarily the ones taking huge risks on other people’s liquidity deposits which need to be redeemed at par. Investors have no need to redeem anybody’s money at par. The securitization of loans is a baby we don’t want to throw out. There’s a whole lot of bathwater. The incentivization structure of hedge funds is obviously perverse towards taking on too much risk. The use of the sharpe ratio as a measure of risk is also perverse. It equates risk with volatility of returns and thus which hedge fund you should choose. Spread trades are inherently low volatility, until they’re not, but if you make a few million on the way on OPM, who cares? The deeper question to me is not why did the lending standards loosen, they loosened because investors still provided the funds to do so and lenders found increasingly inventive ways to get people to afford homes. The bathwater then, is incentivization structures (which should be easily enough regulated by markets, if they were to choose to do so), idiotic ideas about risk in finance and why on earth the securities could get the ratings they got? The idea of the fat tail has been around for a long time. There should be triggers for estimating a fat tail when you start to see all of the above factors coming in – higher LTV ratios, Debt to Income, Documentation of loans and — wonder upon wonder, maybe a cap rate estimation on equivalent rent.

Here is my understanding of the events leading to the sub-prime debacle. The Fed first dropped interest rates in response to the dot-com crash, recession of 2001 and 9/11 attacks. This set off a home refinancing boom that required many more mortgage brokers to be hired. When the refinancing boom came to an end, these additional people employed in mortgage financing increased competition in residential lending. Rather than compete in the prime mortgage segment of the business with lending behemoths like Wells Fargo and Chase, they entered the sub-prime segment.

Sub-prime mortgages originated in 2002 had respectable CLTV and Debt-to-Income ratios. The MBS and CDO assets that had these mortgages as underlying assets performed as expected. However while the ratings agencies that were backward looking continued to rate the top tranches very highly, the underlying mortgages originated had progressively worse characteristics. At this point the ratings arbitrage or more accurately bait-and-switch takes place.

The poor characteristics of the sub-prime mortgages were obscured for a couple of years by the high home price appreciation. But when home prices peak problems in the mortgage market are revealed and defaults shoot up. The “most sophisticated” investors did not become less and less sophisticated as time went on. The took their eyes of the ball and were victims of a bait and switch scheme.

My impression is that the major failure here was in the regulatory response. No one had the charter AND the will (given the political climate) to address fairly glaring gaps in underwriting standards and in transparency rules for those assembling the CDOs/etc.

But of these, the originations seem the biggest problem. Would there have been any crunch if the defaults had not started climbing so rapidly? And would they have climbed so rapidly if the borrowers had been credit-worthy at market interest rates (vs. teaser rates)?

Joseph Somsel: Thanks for introducing the mathematical language of control theory here. It’s a pity the word “control” is used since it has a very pejorative ring in a political context. The type of regulation needed would not have involved suppressing innovation or “controlling” behavior beyond ensuring accountability. You originate it, you suffer (to some degree) from a default — something along those lines. No need to go ban a lot of financial innovation, just common sense rules like “no NINA loans”.

Distributed controllers can be used rather than centralized governmental controls. Markets are self-correcting and efficent markets behave like PID controllers if information is fast, transparent, and correct. Maybe too many market participants at the loanee level lacked information and self-control?

Jaqa’s post supports my thesis about institutional inertia at the originator level.

What’a a “NINA” loan? Looks like the market is suffering from too many “NINI” loans!

Perhaps “sophisticated investors” in the financial regulatory sense of the word were taking on all this nutty risk, but it doesn’t look like “knowledgeable investors” were. Portfolio lenders and especially the GSEs, the most experienced investors, were dropping market share, while hedge funds, pension funds, foreign central banks, etc. were all jumping in. And PMIs were losing market share to whoever the heck it was buying all these securitized piggyback loans. It certainly looks like the most knowledgeable investors were backing off during this time period, while the rubes were pouring in.

oops. Anonymous was me

Joseph Somsel,

My guess is the PID loop was linearized about a point where the system was stable but then the system shifted too far from the linearization point and blewup.

I’ve played with PID controllers and observed that behavior.

I have a feeling that economic/financial systems are way to complex for simple control theory.

Why did the “most sophisticated” investors apparently become less and less sophisticated as time went on?

Because hedge funds start out chasing arbitrage, and found it, in financial vehicles that “always” moved counter to each other, and other things. As more and more chase the same arbitrage, the yields naturally drop. When yields drop, you leverage in order to get those same yields, because, hey, the model is right except on events of measure zero. Except everyone has figured out your same model, which means by your very theory that that arbitrage isn’t going to last. Eventually that low-probability event becomes a large enough probability that it happens. If you’re leveraged too much, you may not have enough liquidity, and boom.

That part of the story has been repeated many times over in the markets. (Of course, to the degree that the hedge funds suffer the losses, I won’t lose much sleep.) One of the twists here is that, instead of just leveraging more, easier and easier standards on the high-yield debt were also sought.

The CBO’s testimony last month does still show that the change in foreclosure rates is very different depending on region of the country. The hottest markets are seeing the sharpest fall. (And Michigan, which was never that hot but has had a one-state recession for a while.)

Tim Duy’s statement over at Economist’s View in Fed Watch: Absolutely Maddening that,

“The central delusion that propelled housing to new heights the belief that housing prices only go up has been dispelled. No amount of easy credit is going to jump start the bubble now.” juxtaposes interestingly with the question above that asks, “What is the significance of the fact that the most recently issued subprime mortgages are the ones that are running into the biggest problems?”

Could it be that the supply of greater fools for real estate has been completely exhausted? That the age of “Peak Greater Fools” is behind us? That more can be extracted from the depleted Greater Fools Fields only by evermore intensive methods with side effects so obviously damaging even the US financial system will decline to employ them?

I remember as if it were yesterday the moment some young Japanese friends in Tokyo remarked to me that they were thinking of buying a condo, but had decided to wait a few years, because they’d be cheaper then.

It’s a long way down.

Why? Greed.

Greed is supposed to allocate resources efficiently …but unfortunately no one was watching the store.

This bubble should have popped a long while back, but it was kept alive by everyone involved …the mortgage companies, rating agencies, realtors, appraisers, CLO/CDO creators, flippers, etc. Pumping and dumping as efficiently as any internet ponzi scheme.

Now the bubble is huge. And all that debt has to be paid by someone.

I read another interesting article today. They said that yes, the subprime will be ugly and Banks will lose alot of money etc. But the 2nd wave is when a large percentage of non-sub-prime owners property value drops below the loan value. Will they walk away? I guess we will see…

Kind of interesting that while the underwriting standards steadily disimproved from 2000 onward, the loss experience on vintages actually improved from 2000 to 2001 and from 2001 to 2002 and from 2002 to 2003 as it peaked in 2003 and 2004, thence disimproving from 2004 to 2005 and onward.

Seems to me that there’s a conventional “asset inflation improves loss experience” cycle going on here that explains a lot of the data . . . . .

It’s like getting stuck with lots of overvalued tulip bulbs that you bought on credit….

As to the PID controller analogy, every market participant does something like a PID calculation in judging risk/return of market movements for their transactions.

It’s only an analogy although I think there is some underlying, common principles.

October 17, 2007

US Inflation numbers were announced today and seem relatively benign – while the headline number ticked up for the month and trailing year, the core rate remained steady at 2.1% for the year. Housing starts continued to decline to the horror of many s…

Why did the “most sophisticated” investors apparently become less and less sophisticated as time went on?

One idea that I would like to see explored is the the ‘most sophisticated’ investors were actually unsophisticated retail investors with a lot of money.

We’re hearing a lot in Canada of the hardship that is resulting from the freezing of the ABCP market – but to date, I have heard of only three actual institutional investors who have take a serious hit: National Bank, the CDPQ and Dundee Bank. The first two of those three may have had a strategic interest in the market, rather than it having been a straight investment (I’m speculating here!); Dundee was a very minor player of no importance to the overall health of the financial system that has been rewarded with a loss of its independence.

Those who have been hurt badly have been companies that happened to have a lot of cash (from a recent underwriting, for example) that was invested by the CEO or CFO … very smart men, I’m sure, and very good at mining or oil exploration or whatever it is their company actually does … but not people who necessarily have any more expertise regarding markets, risks, returns and diversification than my grandmother.

So they put a huge amount of cash into a single asset class – sometimes a single issuer – without much more reason than a single credit rating and a sales pitch from the dealer.

So … what’s needed is some analysis of just who, exactly, is taking the hits on this stuff. And who, exactly, is picking up AAA senior tranches at 85 cents on the dollar to hold until maturity?