The Oil Drum calls our attention to Satellite O’er the Desert, a website devoted to trying to interpret Google satellite images from Saudi Arabia.

Satellite O’er the Desert is produced by someone calling himself “Joules Burn” (who says scientists lack a sense of humor)? JB was inspired by the careful effort by Oil Drum’s Stuart Staniford to sift through the limited information publicly available to try to ascertain the current production status of Ghawar, the world’s greatest oil field, which in recent years has accounted for perhaps 6% of total world oil production all by itself. I discussed the implications of Stuart’s findings in a post at Econbrowser and an article in Atlantic; (by the way, the publisher has now made the latter openly available to all).

JB’s contribution is to note that the satellite images from Google Earth allow us to identify the precise location of individual wells in the Arabian Desert. For example, the photograph below shows two wells side by side. By following their respective pipelines (an arching northeast curve from the well on the left, and a jagged southeast line from the well on the right), JB determined that the well on the left was producing gas, while the one on the right was producing oil.

|

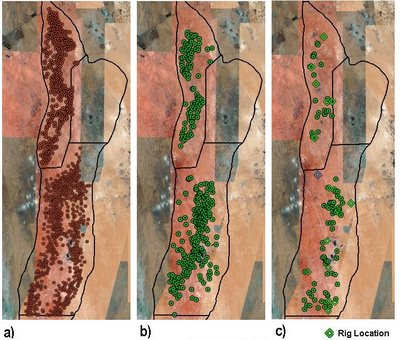

You can then line up the locations of all the oil wells with known maps of the Ghawar oil field.

|

JB further is able to date specific Google images,

and in many cases match picture details against other known dates. The left panel below identifies the oil wells JB found for the northern part of Ghawar. The middle panel shows wells drilled some time since 2000, and the right panel wells drilled since 2003.

|

One of the most surprising things to me about JB’s results is how much of the recent huge increase in Saudi drilling effort seems to have been devoted to Ghawar itself, particularly the northern field which, if I am reading this correctly, cannot have much production potential left.

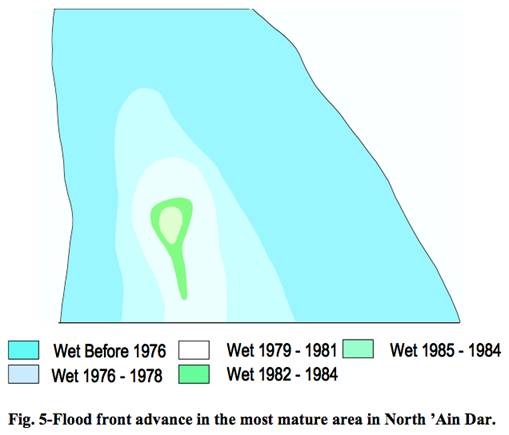

JB’s next task was to line these well sites up with publicly available technical reports (which typically intentionally concealed the exact location discussed) and with some of the conjectures and inference that Stuart arrived at. For example, Stuart concluded that the following published schematic of the height of the water-oil contour at different dates described the northernmost thumb of Ghawar:

|

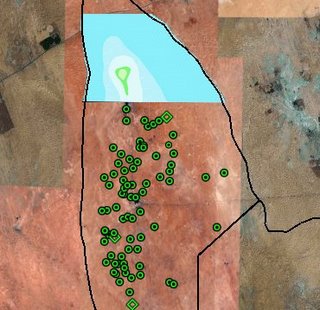

JB superimposed Stuart’s inference on the satellite map of new wells and confirmed that no new wells have been drilled in the area presumed to have been all water by 1984, though there has been a surprising amount of activity just south of that area.

|

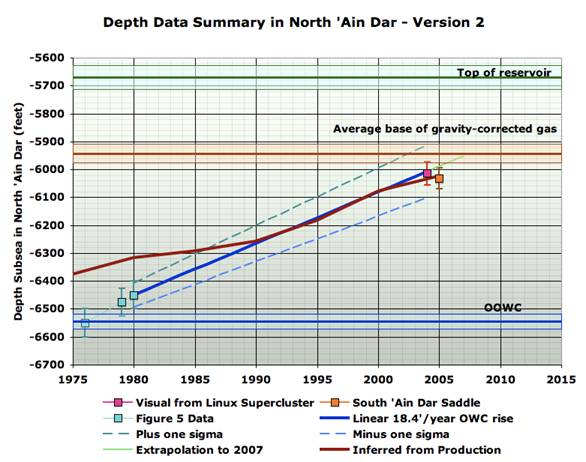

On the basis of the presumed alignment of the schematic with known depths, Stuart then inferred the three points indicated by the turquoise rectangles on the graph below, which plots the date on the horizontal axis and the depth of the oil-water contact on the vertical axis. If the trend that Stuart inferred from a number of other sources is accurate, Stuart’s graph implies that recent production would have come from about the 6000′ depth, near the top of the original reservoir.

|

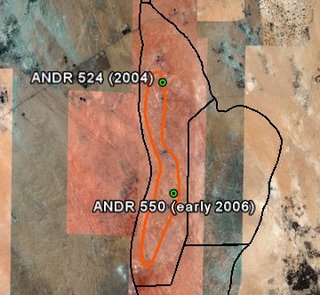

JB believes he has been able to infer the specific locations of two wells described in a recent Saudi Aramco technical report, described as having been drilled in 2004 and 2006, and both placed near the 6000′ contour (indicated by the orange line).

|

Let me end by quoting a couple of JB’s own conclusions from this effort:

the re-drilling of Ghawar– even excluding the much lauded Haradh III increment– can justifiably be classified as the largest Saudi Megaproject, at least in terms of wells drilled. And given the observed fact that virtually all of Uthmaniyah and ‘Ain Dar have been filled in, there is considerably less room for further development to maintain current production rates.

At the time reflected by these graphics, there was probably remaining oil to be had in a thin layer at the top and in isolated pockets of stranded oil, but it can’t last long at historical production rates for this part of Ghawar.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

Saudi Arabia,

peak oil,

Ghawar

I just have to say that stuff like this illustrates why the internet is one of the greatest inventions since the printing press. This type of analysis would have been impossible by an individual 15 years ago. Millions of smart people can now accomplish more than all of the analysts at the CIA — and make the results available to the public.

There is a reason why they cannot increase producion. Peak oil is probably here.

Jeff

Great detective work by JB! Seems plausible, his conclusion.

I am more skeptical about this type of analysis. Granted that we can’t do much better due to the secrecy of the regimes involved, still we need to keep in mind that the quality of the data is incredibly poor. It is to their credit that analysts are able to pull anything out at all, but at the same time we need to be skeptical about the details and not push the analysis too far.

In March 2007, Stuart Staniford published an article at The Oil Drum titled, “A Nosedive Toward the Desert …Or, Why the Decline in Saudi Oil Production is Not Voluntary”.

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/2331

At that time Saudi production had been falling for several months. Stuart’s analysis claimed, “Since late 2004, KSA have entered a new era where they cannot raise production in response to demand side needs, and instead the major features of the production curve correspond to supply side events.” He extrapolated the trend forward based on his analysis and foresaw continued production declines. His graph suggests a production level of 7.6 Mbpd by the end of 2007:

http://www.theoildrum.com/files/ksa_scenario_0.png

However, instead the Saudi decline was arrested almost as soon as Stuart wrote, and in fact production then increased over the course of 2007, up to about 8.8 Mbpd in the most recent reports.

In general, I don’t think this kind of analysis has a very good track record. We will know more of course in the next few years, but at this point it seems highly speculative to put much credence into these attempts to read the Saudi tea leaves. The CIA has got to have the best people in the world at this kind of thing, and as we know they have had a number of notorious intelligence failures in recent history.

“The CIA has got to have the best people in the world at this kind of thing”

I don’t know if that is a justifiable or accurate statement.

Hal,

Your use of that picture out of context is quite misleading. In the text of that piece I wrote:

The green line was never intended as a specific quantitative prediction as I quite clearly said in the text, and indicated in the chart with the question mark. Nor did I take a position on when declines would be arrested in that piece – “anyone’s guess” was my statement about timing.

(In the very first piece in that series, Saudi Arabian oil declines 8% in 2006, I did say that “Declines are rather unlikely to be arrested, and may well accelerate” without any evidence for that conclusion. I think it would be fair to criticize that sentence, which was written in too much haste. By the following week I had realized that the declines had to stop at some point and that I didn’t know when that would be.

)

Of course, in subsequent analyses, we have discovered a far more detailed and comprehensive picture of what stage of depletion various parts of Ghawar are in. By and large, the incredibly diligent work of JoulesBurn appears to be confirming the broad conclusions that Euan Mearns and I reached.

If you want to criticize the work, you would be better addressing that rather than engaging in misleading cherry picking exercises from the early pieces.

Couple observations on Hal’s critique:

1. Introducing the CIA is a red herring, and not only because of the potential politicization of that famous failure.

2. What are the specific aspects of Stuart and Joules Burns analysis that you think may be wrong, or induce errors? E.g. are they not finding wells using the satellite imagery?

My concern with this type of analysis is not with the specifics, but with the general methodology. I would like to see some evidence that this kind of indirect detective work can be successful in making predictions.

Apparently I was wrong to take Stuart’s early 2007 analysis of Saudi production as predicting that production would continue to decrease. I would like to know what predictions he actually did or does make, or what predictions Joules Burn is making today.

I’d also like to see some examples of how this methodology has been successfully applied in the past.

Let me add some specific points to justify my skepticism. Cognitive science researchers have studied for decades how people interpret data, make predictions and execute plans. Generally, they have found that people are bad at all of this. Interpretation and analysis is full of biases and errors. Plans and forecasts are completely mistaken and unrealistic. Where things succeed it is often because the errors fortuitously cancel out.

I would encourage Stuart, and anyone else interested in pursuing efforts to make predictions regarding peak oil or any other such difficult topic, to study the field of cognitive biases. These problems are far more pervasive and insidious than most people realize. Only by becoming aware of the scope of the problem can researchers be informed of the magnitude of the task they face.

A classic example is overconfidence bias. People who make claims of which they are 99% sure are actually right only about 80% of the time. The tendency to place too much confidence in one’s ideas and abilities is nearly universal, and is one source of incorrect forecasts. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases for a long list of similar biases and errors.

Another relevant example is Kahneman and Lovallo, “Timid Choices and Bold Forecasts: A Cognitive Perspective on Risk Taking,” Management Science, Jan. 1993. This describes two different approaches to forecasting, the “inside” and “outside” methods. An inside forecast depends on details of the present situation and brings together as much scenario-specific information as possible. The outside approach instead looks at how the current problem compares with other similar problems in the past, and draws conclusions based on generalizing to this larger class. Their conclusion was that the inside view is overwhelmingly preferred by analysts and is the natural approach to take, despite its manifest failure to deliver adequate results. Stepping outside to compare the present situation with related cases is an unnatural approach that is seldom adopted spontaneously.

The kinds of predictions which have been highlighted on The Oil Drum and similar peak oil sites seem to me to have all the hallmarks of inside-view analysis: highly detailed, case specific, focused on scenarios and extrapolations from present conditions. These are exactly the characteristics which tend to indicate poor quality predictions. An outside view would instead compare with other cases of claimed near-term resource exhaustion, of which there are many examples over the past century or so. It would focus on why this case may be similar to or different from those other examples. Research shows that this kind of analysis is usually going to be more accurate than inside-view detail-based forecasts.

Hal: Your point is well taken.

I tend to ignore any predictions, thinking more probabilistically in an extremely fuzzy way, e.g. the housing market seemed increasingly overpriced but when it would end, and how, seemed impossible to predict. With energy, it has seemed that the spread between supply and demand were under pressure and with Stuart’s previous data, and this information, I continue to believe that this will be the case for both geological and production reasons (CERA notwithstanding).

Like I said: extremely fuzzy.

Hal,

Satellite o’er the Desert probably won’t make a lot of predictions about when Saudi (or world) production will peak, as I feel there are too many variables. What I am trying to do is bring to light objective information about the state of the Saudi fields. Counting wells and comparing with earlier published surveys is rather objective, although mistakes can be made. I might make conclusions based on the amount and concentration of drilling activity and other information about the state of the field, and these will of course be subjective. However, other people can look at the same data and come to their own conclusions. My aim is more to ask and provoke questions rather than to provide all the answers.

Much of Stuart’s work is slanted towards determining an independent estimate of how much oil is left. You might quibble with the quality of the information used to make this estimate, but it is certainly not “reading tea leaves”. And based on the additional information I have gleaned from Saudi Aramco publications, his estimates appear reasonable. Saudi Aramco of course has much better information on which to base a prediction of future production potential. However, their potential for bias by them is much higher. Why? Because they really want to believe, and want the world to believe, that their oil endowment will ever run out. At what point does the potential for bias overwhelm objective data? Bias is always present. The key is to remain open to evidence contrary to one’s position. Many other outside analysts make wildly optimistic predictions with absolutely no objective data behind them. Are they beyond scrutiny or immune from the biases you cite?

As for me, I have come away rather impressed by the Saudi Aramco engineers and scientists but much less so by the talking heads at the top. The geology and history beyond the oil fields of Saudi Arabia is fascinating, and I invite you to look over what I have posted so far as well the articles to come.

Stylized facts:

At the risk of hi-jacking the thread….

One policy option on the supply side would be encourage or somehow facilitate the exploration and development of new light, sweet crude oil basins.

Yet, US Mid-East foreign policy has consistently acted to discourage investment, exploration and development in two key countries: Iraq that once had the world’s 2nd largest reserves of light sweet crude, and now Iran, estimated to have the world’s 2nd largest reserves of light sweet crude.

This is a very curious puzzle. It suggests two perhaps three possibilities:

1.) Oil is no longer the strategic commodity it once was.

2.) Something else in the Mid-East is one helluva lot more important than national security or material per capita wealth.

3.) Or, maybe the leftist analysts are right; it is indeed cost-effective to militarily procure oil reserves.

My out-of-the-window peering suggests that aggressive colonialism since the mid-20th century has resulted in massive losses of social wealth for the aggressor. (Typical leftist assumptions are wrong.)

I’m also inclined to believe that this is an area where American economists, in fact all economists, could indeed have an enormous social impact. Buy/take decisions are well within the mandate of the profession. best wishes -Erik

Much of Stuart’s work is slanted towards determining an independent estimate of how much oil is left.

If that’s true, it strikes me as a bit of a fool’s errand. How much oil is left in the earth isn’t really all that relevant; we care only about how much of it we will be interested in extracting, which depends much more on future developments in exploration, extraction technology and the economics of alternatives.

But the peal oil “proponents” seem instead to be relishing with glee the impending slide into chaos, anarchy and mass extinction they foresee. Armaggedonites of any stripe strike me as ridiculous.

A little article in the WSJ on the subject

http://blogs.wsj.com/environmentalcapital/2008/02/12/big-peak-oil-debate-redux/

“only about how much of it we will be interested in extracting”

And if we are interested in extracting it, the amount of oil in the ground is very important. As you can see from the price of oil in the last few years, we are still very intereted in extracting it.

The question of how much oil is in the ground is very important today. Particularly to those who have money to invest.

“peal oil “proponents” seem instead to be relishing ”

Straw man. I wish we could get beyond this type of labeling and characterization. Those who investigate the phenomenon of peak oil fall into many different categories: technologists, economists, survivalists, racists, extreme-environmentalists, etc.

Hal:

FWIW I have read quite a bit about cognitive biasses. My best guess is that overconfidence in one’s projections is adaptive – evolution has selected the degree of overconfidence humans have as the optimal way to function in an uncertain environment.

Thinking about this with some background in AI, it strikes me that this is likely because the world is much too large and uncertain for any rational agent to solve any meaningful optimization problem in it. An agent that sat and waited to act until it has fully analyzed all problems and then produced an optimal unbiassed forecast on which to make planning decisions would take too long to act, and also would fail to gather the additional information that taking some course of action would result in. In the business community this is known as “paralysis by analysis”.

So evolution has endowed us with a tendency to overconfidence in our predictions, and then a tendency to stick to our plans in the face of mild contradictory evidence (confirmation bias). This avoids the problem of thrashing back and forth between multiple plans when small changes in the available information switch what is the optimal prediction/plan.

So, rather than seeing these cognitive heuristics as bad and irrational, I see them as the best available tradeoff evolution was able to come up with for directing a primate of limited rationality in a very large and complex world. Since the world has only gotten more complex, they probably still have value.

The question about peak oil is one of whether societies natural tendency to ignore it (confirmation bias supporting our existing working assumption that we can continue to grow our civilization without worrying about resource constraints) is still a reasonable course of action in the near-term or not. I don’t see any way to settle this question other than detailed investigation of the issues, debate with others interested in the question, etc. If indeed it’s a serious near-term concern, then the number of people thinking so and searching for solutions will continue to grow. If it’s not a serious near term concern, then falling prices will ultimately make that clear and everyone will move onto other more useful concerns.

As to what I really predicted – I suggest that what I was willing to bet money on might be a good guide for the positions I had the greatest confidence in.

Posted by: E. Poole:

“3.) Or, maybe the leftist analysts are right; it is indeed cost-effective to militarily procure oil reserves.”

Remember, the key is whether or not it’s cost-effective to the *decision-makers*; the rest of us can just suck it up.

“My out-of-the-window peering suggests that aggressive colonialism since the mid-20th century has resulted in massive losses of social wealth for the aggressor. (Typical leftist assumptions are wrong.)”

See above.

I think this is pretty genius.

I agree it’s not concrete to make projections, but it does lend meaningful insight. You have to make best of the information available.

Ever since oil crossed 60, I have been thinking the Saudis are hitting peak oil, at least for existing drilling plays.

IAre rising prices not suggest this? ESPECIALLY when SA has tried and wants the price to be lower and not to have spikes. SA has been operating at max capacity and they would bring more online if they could. SA is waiting for new capacity to be built which takes a minute.