Last week was a tough one for the optimists.

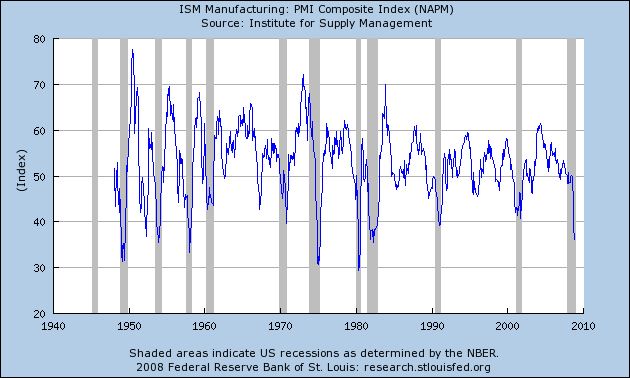

In addition to dreadful numbers for auto sales, last week the Institute for Supply Management reported that its manufacturing PMI index fell to 36.2 in November. A value below 50 indicates that more facilities are reporting deterioration rather than improvements in categories such as orders, production and employment. The index never fell below 39 in either of the previous 2 recessions.

|

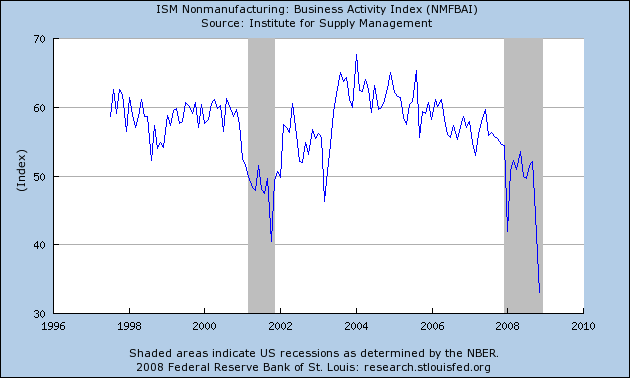

ISM’s related index of business activity constructed from a survey on nonmanufacturing establishments fell to 33.0 in November. We don’t have a long enough track record of that index to know what it requires to get a reading that low.

|

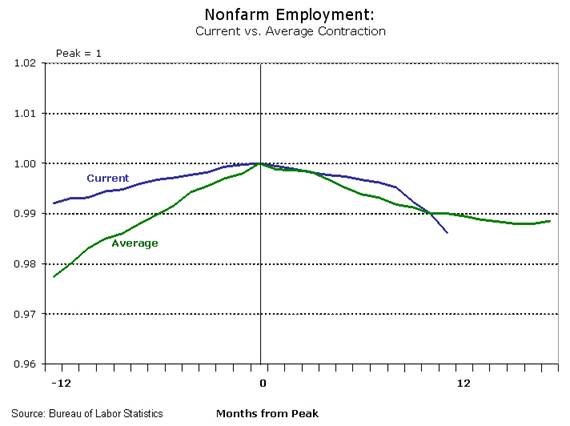

But the real attention last week was on the loss of 533,000 jobs during the month of November reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Friday. That’s a 0.4% drop, the biggest percentage drop in 28 years, and part of broader employment picture that Ian Shepherdson called “almost indescribably terrible.” Notwithstanding, Dave Altig did his best to describe it, perhaps as something not so terrible after all, by comparing the decline in employment since December with what was seen on average during previous postwar recessions.

|

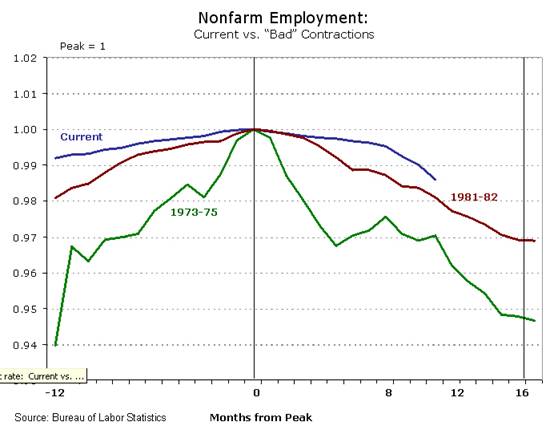

By that measure, this looks a little worse than the average postwar recession, in part, Dave notes, because it’s already lasted one month longer than the postwar average. If you compare the current recession with the two longest and most severe postwar recessions (1973 and 1981), we’re maybe not quite as badly off now as we were then, at least if you trust the preliminary data.

|

But there’s another comparison we can look at along these lines that’s much less reassuring. One of the developments that helped get us out of previous downturns is that the Fed responded to the recession by lowering interest rates. The blue line in the graph below shows the average behavior of the fed funds rate in the months following the recessions of 1957, 1960, 1969, 1973, 1990, and 2001. I’ve left out the somewhat anomalous 1980 and 1981 recessions, in which rapidly changing inflation expectations played a key role. The red line shows the fed funds rate during the current recession. The Fed cut rates more quickly and farther this time around than in any of the other 6 comparison downturns.

|

Why does that trouble me? It means that the Fed did everything it could from the very beginning this time, and it wasn’t enough. The average fed funds rate in November was 0.39%, meaning that even if the Fed cuts its official “target” for that interest rate to 0.5% or even 0.25%, it’s not going to do anything for anybody. The main weapon we’ve always used in the past in this kind of situation is now out of bullets.

If a recovery begins soon, Dave’s diagrams indicate that this wouldn’t be regarded as all that serious a recession. But I see no signs that a recovery is about to begin.

Technorati Tags: employment,

recession,

macroeconomics,

economics

This recession was caused by the use of the blunt tool of FED monetary policy, when they started hiking and kept hiking right into the teeth of the debt bubble. The FED in addition was hiking as oil was rising, all through 05 and 06.

What should have occurred instead was a tightening of lending standards.

There is a current little myth going around that Bernanke understood that oil’s price rise this decade was not inflationary. I see no evidence for that. On the contrary, he totally took the bait that it was inflationary, never considering that oil was already tightening conditions during the housing bubble. Oil re-priced above 40.00 in 2004.

The FED left rates too low for too long. Then brought rates up too fast. They did this in conjunction with oil rising, and, simply spooled out their rate hikes without any help from regulation. Then, at the end of the hiking campaign, in 2006, Bernanke roared hawkish language at the market in 2006, and acted a little strangely, confusing everyone.

Conclusion: the FED was completely unaware of the size of the bubble they had already created, when they started hiking.

In short, the monetary policy mistakes were all made earlier in the decade. So, it really didn’t matter that Ben was giving back the hikes starting last Summer.

Bernanke is a smart guy. But, appears to have had less appreciation for the bubble than many smart posters and commenters on the better macro chatboards. At Silicon Investor’s Credit Bubble Board, most of us picked out the pathway of this situation years ago.

Monetary policy lag? Seems like you’ve cut the lag down drastically from what it historically has been to declare that it wasn’t enough. How much lag do you think we should see?

The Commercial Paper release today showed some relief in the A2/P2 spread, albeit still historically high; could be a fluke, though… as the 30-year Treasuries haven’t weakened. Credit markets seem to affirm your assessment.

As defense analyst Colin Gray Writes in a recent book about the near-term possibilities of major conflict, “Another Bloody Century,”* when considering optimism and pessimism, “optimism is apt to kill with greater certainty.”

— Fear of China by Robert D. Kaplan in The Wall Street Journal, on page A14, on April 21, 2006.

Nice graphs, Professor.

To me, it seems that the key indicator of how severe this downturn is going to be is the ratio of household debt (L.1 in the Z.1) to GDP (F.6 in the Z.1). Over ’46-’79, the ratio never got above 50%. Beginning in ’81, the ratio went monotonically up from 48% to 100% in ’07.

Until that ratio returns to historical norms (i.e., debt is written off; all efforts to stimulate GDP will fail, as it is nothing but taking from the more productive and giving to the less productive), households will see increasing pressure on their finances and will continue and accelerate their rational efforts to save.

Yep, unfortunately, the rise in unemployment has just gotten started.

Secretary Mellon had the correct solution for the ’29-’33 downturn, and his solution is the correct answer, today.

Really great post, James.

I am a bit intrigued by the hyperbole, the “Great Recession” and even “Second Great Depression” talk. On what basis are such concerns grounded when the unemployment scenario is far far FAR from dire? (as shown on “Current vs. ‘Bad Recessions’ employment” graph)

This recession doesn’t feel as bad as the 1980 recession yet. The main difference was then one couldn’t afford to borrow money at 20%. Now no ones qualifies. Unemployment if I recall was around 10%. Gas was $1 a gallon. We all turned conservative from dress to politics.

Se the referenced link for an “animal spirits” argument that the recession will end soon, although GDP will stabilize at a much reduced run rate, and “animal spirits” (confidence) will recover shortly.

There is one single fact that matters wrt predicting what is coming. There are no good statistics coming out, and most data releases are worse than the useless economists predicted. And many of the data are getting worse. We haven’t even hit an inflection point yet, let alone a turn around.

The only bullish argument anyone is making is “Look how long things have been bad. This has gone on longer than usual.” That is not an argument, and it has no predictive value. i.e. there is no bullish argument.

@ Keith,

They said the same thing during the Great Depression…… hmmmm.

I know its a cliche but maybe the credit card really is maxed out. after all, what did private equity do but push the central banks logic to its conclusion?

… so much for the “great moderation”! 😉

JDH wrote:

One of the developments that helped get us out of previous downturns is that the Fed responded to the recession by lowering interest rates. The blue line in the graph below shows the average behavior of the fed funds rate in the months following the recessions of 1957, 1960, 1969, 1973, 1990, and 2001. I’ve left out the somewhat anomalous 1980 and 1981 recessions, in which rapidly changing inflation expectations played a key role. The red line shows the fed funds rate during the current recession. The Fed cut rates more quickly and farther this time around than in any of the other 6 comparison downturns.

Why does that trouble me? It means that the Fed did everything it could from the very beginning this time, and it wasn’t enough.

We live in a strange world. I can remember a time when people would try something and when it didn’t work they admitted it and then went back to find out what would work. Today we live in a world where when something doesn’t work it is because it just wasn’t enough. If only we could do it just a little more. Not only that when the data doesn’t support the theory the data has to be wrong not the theory so just leave “out the somewhat anomalous 1980 and 1981 recessions.”

But you know what. The men who actually began political economics are not confused at all. They would look at our economy and say it is just what should result from such policies. Oh well….

Pegging the curves for Non-farm Employment in the center is a nice trick, in the “Mathematician Reads The Newspaper” sense. It pretends that employment begins each period at some magically calibrated equivalence point, even though everyone knows job growth has been lackluster after the last two recessions….by pegging the center, you get to lift the starting point, when in reality the entire curve probably should be below the average curve.

It was the Fed cutting interest rates into a “solvency” problem while inflation was still a worry that precipitated the current problem. The response of the markets to the Fed rate cuts was a collapse in the dollar and a spike in commodity prices particularly oil. That jump destroyed what little solvency households had.

In the recession employment graphs, the big takeaway is the portion to the LEFT of the 0 start of the recession.

In this recession, the job gains in the year before the recession were very weak, compared to all other recessions. This indicates that while the job losses have not match 1974 or 1980-82, those recessions were preceded by strong job gains.

In other words, this recession has already gone below the t(-12) job number. That rarely happens, even in severe recessions. Even 1974 did not have that.

Again, the t+12 job number is already below the t-12 job number. That has rarely happened in prior recessions, and only happened in 1981-82, because of the 1980 recession.

So the ‘Great Moderation’ is alive and well. Look how jagged the 1974 line is.

Indeed, we have only added 3.6M jobs in the last 8 years. If there are 1M fewer jobs by the end of 2009, then there would have been only 2.5M jobs in 9 years. The Jan 2001 peak was an unusually high peak, but still.

no GK, the great moderation is not alive and well. read the bernanke speech again. he ascribes the greater stability (which we now know was illusory or deceptive) to more advanced macroeconomics and its influence on policy makers, particulary monetary economics and its influence on central bankers. now contrast that with what jim hamilton is showing in his post.

I am not sure if this is possible but is there a place to find this information to add to the charts, COLA, raises back in the 70s and 80s. I worked summers for a meat packing plant 81-82-83 and during that time pay went from $7.70 an hour to $11.19hr. I am not sure if that was unusual for most industries but how much did that cushion the down stream job losses.

What’s really worrisome about this recession is that it’s difficult to see what gets us out. We need to be drastically reducing expenditures, both public and private, on health care. Consumers need to drastically reduce debt. Government needs to be spending, but not wastefully, as it has with the financial bailout. By the time people figure out that most of the initial bailout money has been misapplied, will we be able to raise additional funds? And then there are the wars, which so far have yielded no stable solutions.

So… how does the economy get re-started?

In basically every recession people always fret about “what gets us out”. The thing about recessions is that they always appear to be a downward spiral. The fact is that reduced borrowing costs at some point will have an effect. Government spending will also have an effect. There are some substantial private cash reserves out there, though they are not reflected in the savings rates. We do have the tools to recover. One thing we have going for us is that inflation is not the slightest bit of a concern right now.

Brian D Quinn: “appear” to be a downward spiral? As opposed to, say, actually being in a downward spiral:

http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/census_economy;_ylt=AvJgNgJMWf4eJXhbuiRTyrYDW7oF

Sometimes it’s better to acknowledge what’s broken,

since it’s a prerequisite step to fixing anything and

everything.

As far as ‘what gets us out’, the elements of a recovery are already in place :

1) Low oil prices

2) Low interest rates for several months now

3) A stronger dollar than before

4) Technological advances continue uninterrupted

5) Population growth slowly starts to mop up housing inventory

The only thing in the way is fear. Once fear subsides and people resume their ways, a recovery happens.

The only thing in the way is fear. Oh, and real wages. Our two main weapons are fear and real wages and overindebtedness….our three main weapons are…

@GK ..”The only thing in the way is fear. Once fear subsides and people resume their ways, a recovery happens”.

No, not that way.

Obama is going to shift just the people in place,

the establishment behind him want to see. Summers, Geithner, Romer are all members of the goldman sachs clique. Their interests are not driven by emotions like “fear”, rather want a strong cashback after a 750 mill investment named Obama.

Buffetts 5B investment in goldman sachs is dead right:

“www.huffingtonpost.com/2008/05/19/warren-buffet-backs-obama_n_102451.html”

“latimesblogs.latimes.com/money_co/2008/09/warren-buffett.html”.

Fear has not been his advisor.

KnottRP : So a recovery will never happen, according to you.

John Lee : That is an unrelated subject. We are talking about the end of the recession.

@GK ..”The only thing in the way is fear. Once fear subsides and people resume their ways, a recovery happens”.

In full respect for your opinion, again :

No, not that way. Fear is not the only thing in the way to recovery. The end of the recession is dependent also on other factors, e.g. people in power driving the business cycle according to their need. A very related subject indeed. But GK, keep your opinion “As far as ‘what gets us out’, the elements of a recovery are already in place”- you might have a better sleep next night. Cheers.

GK> KnottRP : So a recovery will never happen, according to you.

I never said that.

overindebtedness has several routes to a cure

(default, or dollar devaluation).

real wages have several routes to recovery also.

Folks trot out “fear” as some magical thing that

can be wished away….I submit that there is irrational and rational fears, where the later is grounded on a sound basis which must be addressed.

I get tired of the whole “mental recession” meme…no one is buying it.

This is the deal:

In this harsh environment, the advantages to strapped companies of outsourcing and offshoring persist and are intensified.

This means there is no source of job recovery, none, nada, zilch – under any feasible scenario.

There is one caveat. If the scenario changes wrt our trade policies, then we have a source of job growth.

We need tariffs. They will be an advantage to us. This is so because the flip side of American overconsumption is Chinese overproduction. Tariffs will result in import substitution, resulting in American jobs.

This will be harsh for China, but they’ve been employing mercantilism for their own purposes for quite awhile now, and that’s the breaks.

nyet,

Such tariffs would be in violation of the WTO.

I wish we could put a tariff on oil, though.

James,

Can you extend the two employment charts in both directions, from t-24 to t+24? I think that would be very informative.