Paul Krugman may not be that concerned by the Obama administration’s new projection that the unified federal budget deficits will sum to $9 trillion dollars over the next 10 years. But I am.

Here’s the argument Paul Krugman gave for why $9 trillion maybe isn’t as huge a sum as it sounds:

even if we do run these deficits, federal debt as a share of GDP will be substantially less than it was at the end of World War II. It will also be substantially less than, say, debt in several European countries in the mid to late 1990s.

Political Math (hat tip: Russ Roberts) takes a closer look at Paul’s first comparison:

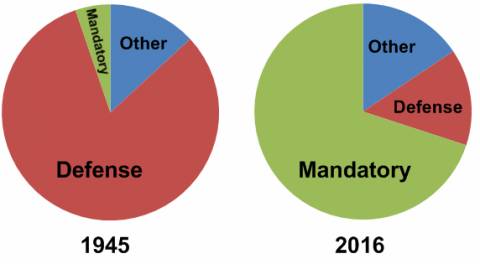

implicit in his observation is the concept that since we did fine after WWII, we’ll do fine now. But the years after WWII saw drastic reductions in the inflation-adjusted debt driven by drastic reductions in spending. Mr. Krugman points to no similar possibility in the post-Obama world…. Back in 1945, at the height of the spending that saw our national debt rise so dramatically, entitlement spending and interest on the national debt made up a meager 5% of our total budget.

|

And whereas in 1945 Americans could reasonably look ahead to a huge decrease in military expenditures, in 2009 when I look ahead what I see is a looming increase in federal medical expenditures.

I also believe it is relevant to compare these deficits not just with GDP but also with current federal tax revenues. $1 trillion is approximately the total personal income tax receipts of the federal government in 2006. My preferred metric for what each additional trillion dollars would require from me personally is to take what I paid in federal income taxes in 2006 and double that amount. To pay off $9 trillion, I’d have to do that for 9 years.

Unfortunately, $9 trillion may not be the whole iceberg.

Diane Lim Rogers highlights the Concord Coalition estimate that current policy would imply a cumulative $14.4 trillion deficit over the next ten years.

You also can’t ignore the off-balance sheet federal liabilities, such as the $5 trillion in debt and loan guarantees from Fannie and Freddie. A quarter trillion dollars worth of those loans we’ve guaranteed are currently nonperforming. That’s just Fannie and Freddie– doesn’t include FHA, FDIC, Federal Reserve,…

If the government tries to double taxes on people like me, it’s in real political trouble. If it doesn’t try to double taxes on people like me, it’s in real solvency trouble.

It looks like we may have a problem here.

Except for the fact that Krugman states right before he makes that argument, “Dont get me wrong: this is bad.”

I guess I personally would paraphrase it differently than, “Krugman may not be that concerned.”

A couple points I would make here are the following:

1. No doubling of personal income taxes is needed. The level of personal income tax receipts by the end of the decade will be substantially higher, probably nearly double because of the rate of nominal personal income growth. CBO estimates that by 2014 personal income tax receipts will stand at $1.729 trillion. Social security taxes, of which half are paid by the individual, will be at $1.121 trillion. Let’s use the approximate halving of that for $560 billion of revenues from individuals, though arguably we should look at the whole amount as being paid by individuals. Add those two together you get to $2.3 trillion.

The deficit projected in 2014 is $558 billion. This would be about 1/4 of the total amount of personal taxes to close the deficits in the out-years. Granted, that would be a substantial amount, but not unmanageable.

2. The deficit is predominantly front-loaded. The deficit in the first five years is substantially larger than in the next six years. There’s not much we can do about this portion. However, the deficits in the out years are manageable at between 3 and 3.5% of GDP. A combination of relatively modest tax increases and spending cuts, such as indexing Social Security benefits for CPI instead of wages, would be able to close the deficits almost entirely in the 2014-2019 period.

3. Assumptions about future revenues are almost always distorted by peaks and troughs of the business cycle. Remember in 2000 when we had the $5.6 trillion ten-year surplus estimate? That was never going to happen solely because economic growth estimates were unrealistic. Similarly, revenue forecasts in 2002 were too modest for the 2004-2007 period. Despite the care in modeling that CBO and OMB engage in, it is likely that they are underestimating economically sensitive tax receipts such as corporate income taxes and capital gains taxes.

The combination of these factors means that we can close the long-term deficit reasonably easily, if there is political will to do so, without drastic actions. Granted, such moves will harm long-term GDP growth so that has to be considered. However, if we eliminate the deficit by 2014-15 we can engage in a long term pattern of waiting for nominal GDP to grow large enough that the debt as a percent of GDP shrivels up, like we did after WWII. In the post-WWII period we barely reduced the nominal level of US debt at all compared to how much it increased. We just let nominal GDP grow over the course of two decades while maintaining a balanced budget.

What ever happened to “Reagan proved deficits don’t matter” from an undiscloosed location? I mean , just asking.

Professor Klugman states in his article “we actually need to run up federal debt right now and need to keep doing it until the economy is on a solid path to recovery.”

My worry is that after the dot.com bubble and the real estate bubble we are now entering a period of equally unsustainable government spending. OK, government spending is not a bubble but it will pop like a bubble when the Chinese stop purchasing our debt.

What if the solid path to recovery isn?t found? I think most people waiting for a recovery assume that before last October the economy was humming along and if we get enough money in the hands of consumers we will return to “normal” growth. But the growth in the economy during this decade was abnormal and unsustainable. That’s not coming back. The real estate bubble allowed the US to live beyond our means and the stimulus seems to continue this.

I’m obviously not an economist and realize my understanding of the subject is limited. I hope that I haven’t lowered the level of discourse with this post. I just can’t shake the feeling that the US economy is in for a brutal awakening. As a nation we cannot continue to rack up debt, public and private, without destroying ourselves.

Me-

Is that the best you can do – apocryphal quotes? Even if it were true, the deficits were much smaller and on a track to zero before the financial crisis. The current administration is completely heedless and seems bent on ramming through their agenda regardless of cost and consequences.

I don’t consider reading anything that quotes The Concord Coalition with Blackstone billionaire Pete Peterson’s “any reason to get rid of Social Security” ploy.

Any country that wastes $1 Trillion on Defense spending for 1950s thinking really ought to look there first. And then of course those wonderful tax breaks Pete Peterson gets from the government along with the subsidies (also read as corporate welfare).

D- on your article sir. Try better next time.

I have zero confidence in projections about future deficits “closing”. At the start of the decade, Bush told us about a new economic discovery called Supply Side Economics and it has a growth engine called The Laffer Curve which would close the then shocking $400B deficit, probably sometime in Bush’s second term. We got down to around $250B for about a year finally, then the economy exploded.

Clinton actually ran counter cyclical policy which gave us a year or two of balanced budget, which lead to the forecast that we would be sitting on a huge pile of money in Ft. Knox today, but somehow we blew that. Plus they add in the then sizable social security surplus as current tax receipts, spend the money, and stick a “non -marketable” treasury note paying 2% into the social security trust fund. So that source of income disappears late next decade and leaves us with a check clearing problem.

Post WW2 we had a top tax rate of 70%, then many, many years of inflation pushing everyone closer to it, until Reagan finally said…enough!

Then going forward, the nature of our economy looks a little murky. Some have great hopes that bio-tech will become the next big thing. So I guess with a little training maybe our displaced auto assembly line workers can become bio-tech scientists. Then we can re-tool auto plants with lab equipment, and get the the output gap to fill up seamlessly, which we all know is where real GDP growth comes from.

There is global warming and alt energy, which I’ve heard could be a big growth driver. And I believe taking our energy costs up by a factor of 3 or 4 could at least add to nominal GDP, if the consumer can find the money somewhere. Not absolutely sure about that since I see total debt numbers for this country have gone from 140% of GDP in 1980 to 375% now, but maybe there is a chance.

Then we can invest in health care in the beginning, increase coverage, and not fear supply-demand-price curve action because we will get cost reductions in Obama’s second term. I know little about the health care industry, because the last time I was in a hospital was when I was born, and doctor visits are infrequent too, but I think this process will deserve some monitoring to see if it plays out as planned.

But I could be wrong about all these things, and maybe the right way to do it is extrapolate economic data from the past.

Uh, oh, the tinfoil hats come out. Watch out, now anyone who wants a balanced budget will be tarred and feathered.

We should return to the PayGo plan used early in the Clinton administration. Now that the stimulus is in effect, there’s no real reason not to. We can write the second stimulus out of money returned from the bank investments in the $700 billion bank bailout. The banks supposedly don’t need the money any more; they can pay back the public money and raise capital out of their executive salaries, as should have been done anyway.

Krugman is counting on a 1% real borrowing cost for the additional debt 40% of gdp. Enough said.

Bumticker – I am an economist and think that your post sums up quite nicely the anxiety a lot of ordinary, non-economists have about the future.

Thanks

It’d be nice to see interest in there. Both government and total.

I have to laugh at Krugman and his followers. He says twice that “this is bad”, but the body of his post completely undercuts those comments. His analysis is superficial and selective, and devoid of nuance. But this is what his fans have come to know and love him for, and the good professor keeps serving it up. Why mess up a good thing?

No need to worry about the Chinese, the fed will just buy the bonds instead.

What are these guys talking about? He’s regularly made comments about how we need to reform some programs to cut spending and how small reductions in Medicare spending can reap enormous savings over the next few decades. Better yet, this doesn’t appear to require huge sacrifices when it comes to quality care. From what we’ve seen, the money that can be saved is, for lack of a better word, now wasted. Just take a look at his column from today:

“As Ive said, those 10-year projections arent as bad as you may have heard. Over the really long term, however, the U.S. government will have big problems unless it makes some major changes. In particular, it has to rein in the growth of Medicare and Medicaid spending.

That shouldnt be hard in the context of overall health care reform. After all, America spends far more on health care than other advanced countries, without better results, so we should be able to make our system more cost-efficient.”

He also makes the point, in the same column, that the various bail out efforts aren’t all being thrown away. At the same time as we are putting money on the table, we are acquiring assets, and while it’s unclear how much we’ll get back, it’s not a total loss.

Now, let’s just say that we added a financial transaction tax that added about $100 billion a year or so in revenue for the next ten years, at least. I’m not skilled enough to know how this would closely affect the numbers (by way of interest costs and so on), but we are essentially looking at an extra $1 trillion in revenue over the same time period. What’s that good for as a reduction of debt-to-GDP?

James, the problem with your argument is that it treats all deficit spending as equal. Deficit spending that is an investment (such as spending in education, infrastructure, and, to a lesser extent, health care) yields future economic growth, growth that reduces the debt/GDP ratio. This is particularly appropriate when fiscal stimulus is needed because monetary policy can no longer be used.

Paul Krugman addresses that in some of his recent blog posts following up on the post you referenced, saying, “The irresponsibility of the Bush years has left us poorly positioned to deal with the current crisis, turning what should have been an easily financed economic rescue into a more difficult, anxiety-producing process.” He then later followed with, “There was a case for temporary fiscal stimulus in 2002, when the economy was close to the zero bound, but most of the Bush tax cuts took effect during a period in which interest rates were well above zero, in fact during which the Fed was raising rates to keep the economy from overheating. This means that fiscal expansion wasnt needed. Now, by contrast, were hard up against zero and have run out of monetary ammunition.”

It’s sad to see Obama’s economic policies being defended most avidly by that proven buffoon Krugman. I’m afraid that with his huge gamble on the Keynesian free lunch theory, Obama is squandering his potential as a leader in moral and social values.

Krugman used to be a pretty good macroeconomist before his current career.

When I want to read macroeconomics, I go to Econbrowser.

“It looks like we may have a problem here.”

Problem? No, just tough choices.

What is the upside of a massive US public debt? It provides unsophisticated investors with a safe secure asset whose real return will likely increase over time. (On this subject see David Andolfatto’s blog post Why the Growing Level of U.S. Debt May Not be Inflationary.)

The USA can choose to implement Nordic level excise/green/pigouvian taxes on fossil fuels. The USA can choose to stop running its foreign policy for the benefit of small, highly focused rent-seeking special interest groups. In that regard, the USA can choose to end US$3 to US$4 Billion in aid, mostly military to the territory and resource-ambitious state of Israel. It can also choose to stop invading and occupying countries that are at odds with this glorious colonial agenda.

Or the USA can choose to slowly fade away just like previous European imperial regimes.

Hemingway —

There’s not much money there — eliminate $1t of spending and you eliminate 11% of the expected debt.

Jim-

I reread your post just to make sure, but the chucklehead Krugmanauts have failed to grasp your argument, and have provided little more than hand-waving counterarguments.

I particularly enjoyed “Now, let’s just say that we added a financial transaction tax that added about $100 billion a year or so in revenue for the next ten years, at least. I’m not skilled enough to know how this would closely affect the numbers (by way of interest costs and so on), but we are essentially looking at an extra $1 trillion in revenue over the same time period.”

Let’s spread that wealth around – for the people!

A country that issues its own non-convertable currency cannot become insolvent or bankrupt; any economics professor should know that! Can anyone explain Japan? More than a decade of deficit spending resulting in a debt to gdp ratio of almost 200%, short term interest rates set at nearly zero for a decade, yet no insolvency, no inflation, no drop in the value of the yen. Anyone explain that? Anyone… Anyone.

Please check out the work of modern monetary economist like Warren Mosler or PROFESSORS Bill Mitchel, Randy Wray, and Scott Fulwiller.

The categories used in those pie charts seem silly.

In my view, the only REAL “Mandatory” category is interest payments on the debt to bond holders. As a corollary, EVERYTHING else is negotiable.

“…If the government tries to double taxes on people like me, it’s in real political trouble…”

Quote by Obama from the beach at Martha’s Vineyard, after reading this column: “If I’ve lost the Professorariate, I’ve lost the nation.”

James, the problem with your argument is that it treats all deficit spending as equal. Deficit spending that is an investment (such as spending in education, infrastructure, and, to a lesser extent, health care) yields future economic growth, growth that reduces the debt/GDP ratio. This is particularly appropriate when fiscal stimulus is needed because monetary policy can no longer be used.

This assumes many things. First, it assumes that federal spending on education is actually improving education. There is little evidence for this. Federal education spending has skyrocketed in the last decade, and no objective measures of outcomes indicate a real improvement in education.

Second, it assumes that that all infrastructure spending increases economic growth. Japan’s experience would prove otherwise – by overbuilding infrastructure, they simply creating a maintenance liability and used up resources that would have been better allocated elsewhere.

Third, it assumes that increasing spending on health care will lead to higher economic growth. Given that the majority of health care spending goes to retired people, I find that dubious at best.

Finally, you are totally ignoring the fact that there are optimum investment levels beyond which additional spending will simply lower economic growth. Build too many schools, and you’ll perpetually eat up resources in building maintenance and custodial salaries that could have been used more productively elsewhere. Spend too much money subsidizing secondary education students, and you’ll drive up the price and divert resources where they would otherwise not go. ‘Invest’ more in health care funding without increasing the supply of doctors and nurses, and you’ll simply create shortages, waiting lists, and drive up costs.

Jim-

I read the full post at Political Math and his critique was pretty devastating. His video on Mass Universal Health Care could be made into a great commercial contra ObamaCare (or should I say KennedyCare).

Thanks for the tip.

“…even if we do run these deficits, federal debt as a share of GDP will be substantially less than it was at the end of World War II… It will also be substantially less than, say, debt in several European countries in the mid to late 1990s.”

As noted, the WWII deficits were temporary and everyone knew it — and that’s not happening this time.

From 1945 to 1948 federal spending declined by 17.2% of GDP — and deficits and the debt came down with it.

While from here on forever, the track for

spending-driven deficits is up, up, up, up, up.

So the comparison by Krugman is plainly disingenuous, in support of an agenda.

Let’s recall what Standard and Poor’s

has projected. Maybe Krugman thinks that’s not a problem.

(And that projection was made before all the recent recession/Obama deficit increases. All the trillions of new debt and lost revenue since then moves those dates forward.)

“As I’ve said, those 10-year projections aren’t as bad as you may have heard. Over the really long term, however, the U.S. government will have big problems unless…”

Except the “really long term” is barely long at all now — about half the length of a conventional home mortgage away.

“James, the problem with your argument is that it treats all deficit spending as equal. Deficit spending that is an investment (such as spending in education, infrastructure, and, to a lesser extent, health care) yields future economic growth, growth that reduces the debt/GDP ratio.”

Greg,

That argument needs a little more info to flesh it out. What is the RoI of education spending? Is it the same no matter what discipline it is spent on? Is it the same no matter what age it is spent on? This current plan is spending on the right discipline at the right age for maximum RoI in NGDP terms? Could anyone possibly predict that decades in advance without devolving into wild guessing? If so, tell me now so I can buy the stocks.

Infrastructure is important to maintain for smoothing commerce. What part of this infrastructure spending is going to make things not just the same but demonstrably better? Faster, more efficient, or less expensive, etc.? I’m not saying we don’t need to maintain our infrastructure, but without some real advance in its effectiveness, you aren’t going to make _more_ money, you just aren’t going to make _less_.

I will posit a theory. I think the current educational opportunities and the nation’s infrastructure are at levels that do not permit large incremental gains. A few new bridges financed with deficit spending are not going to replicate the installation of railroads or the interstate highway system. Between public, charter, and private schools, libraries and the Internet most people that would like to have an education can obtain one. Many states even offer “free” college tuition to their citizens. I am not arguing that everyone in America is well educated, only that the opportunities exist so that they could be. It is no longer a matter of offering something which people desired but lacked the power to obtain; you are now in a position of trying to make them desire it. Like with infrastructure, I do not think the large gains are obviously possible. And, as above, education is in some ways even more sticky than infrastructure. A road can be made without requiring active participation from the dirt, but one cannot force someone else to learn against their will.

Cedric,

Bush wouldn’t know supply side if it bit him in the butt.

Bill Clinton ended up being the second greatest supply sider since the 1920s even if it was by accident. He held down government spending because of his feuds with the Republican congress. He signed welfare reform resulting in a reduction in government largess and an increase in taxpayers. He signed a reduction in capital gains taxes. And additionally the beginning of the Clinton administration is when Greenspan was still using a gold price policy and the price of gold was extremely stable allowing businesses to focus on production rather than protection from monetary errors.

You mentioned the Laffer curve but from your commnet you don’t understand it any better than George Bush. Bill Clinton moved us down the Laffer curve for the reasons I mention above plus he kept us out of any major military conflict.

On taxes pre-WWII, actually Andrew Mellon reduced taxes during the 1920 leading to an extended period of prosperity. Just more proof of the warnings – and blessings – of the Laffer curve.

But generally you are on the right track. Keep studying and keep an open mind.

Professor,

I think you know from my previous comments that I totally agree with your analysis. Keep up the good work.

Thanks for more absurd Krugman quotes. I don’t read everything he writes. His illogic tends to depress me.

Obama has the perfect strategy if he is worried about deficits. Get Congress to move progressive taxes higher. Then the Republican cost cutters get elected to Congress.

Supply and Demand in action. The higher the price of government the less we buy.

ThomasL wrote, “What is the RoI of education spending?”

According to the CBO, it’s 10%. See

http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/91xx/doc9135/AppendixA.4.1.shtml

We can borrow at 4-5%, so investing in something that yields a 10% return seems like a no-brainer.

As for your argument that we have saturated that investment opportunity, I don’t see how you can make that argument in the face of data such as only 70% of kids graduating from high school and only 23% of kids graduating from high school showing readiness for college in reading, math, science, and English. The data clearly indicates that we have a long way to go before every child is educated up to their full potential.

Mattyoung,

You just outlined the road that has been leading us to disaster since WWII – with the exception of a short breather during the Reagan administration. The liberal Keynesians (Democrats) increase spending and deficits to stimulate growth. They then increase taxes driving the economy down.

The electorate then votes in the conservative Keynesians (Republicans) and they begin to cut government spending and also raise taxes to balance the budget. The economy continues to tank so the electorate reelects the liberal Keynesians (Democrats) and the cycle starts all over.

For me: The graphs by Political Math get it right concerning “deficits don’t matter.” It is not the amount of the deficit that is the problem, but what has moved us to a deficit. When we are fighting for our very survival as in WWII, a deficit that is 70% of GDP could very well be our best option, but when we are at peace a deficit of 10% of GDP could be prohibitive.

Once again this takes us to the Laffer curve. The equilibrium point, “E,” on the Laffer curve depends on the needs and will of the taxpayers. War moves point E higher while in peace it will be lower. This can be seen in a tangible wya in the UK tax structure after WWI when they retained the war taxes and their economy tanked resulting in continued high employment. The US on the other hand, through the leading of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, lowered taxes and the US entered the low unemployment of the prosperous 1920s.

Krugman’s repose to this post:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/28/the-burden-of-debt/

Remember, just 8 years ago Greenspan was warning us that if we did not pass the Bush tax cuts that all the bond traders would lose their jobs because they would have nothing to trade.

I think we should take all partisan deficit projections with a very, very large grain of salt.

“If the government tries to double taxes on people like me, it’s in real political trouble. If it doesn’t try to double taxes on people like me, it’s in real solvency trouble.”

Actually what is very interesting to me is that over the past eight years the accumulated debt increased around $4Tr, and according to an article referenced today at Mark Thoma’s site, merely extending the Bush era tax cuts would incur an additional $3Tr over the next.

So effectively, people like somebody, though not necessarily like you, had on average four times as large a tax cut over the past eight years, that wasn’t really a tax cut at all, just a deferral, and now an extension of that logic is on order.

As with the large amounts of debt that have built up over the last thirty years, something seems collectively wrong the operation of the intertemporal budget constraint.

Matt: charts I’ve seen from CBO (or maybe Ross Perot) show spending growth essentially unchanged regardless of the party of Congress or the White House – it’s just the composition of spending that changes. Do you have some good charts that show Republicans *actually* cut costs?

DickF

I was just making some quick bullet points of what the highlights of the last 50-60 years looked like to me.

Bush probably thought Supply Side and the Laffer Curve was something new, but I’m pretty sure Cheney and the Neos new better.

Art Laffer and Robert Riech talk to me all the time via CNBC, so I, Robert Riech and/or Clinton may very well be confused that Robert Riech would have suggested the Laffer Curve to Clinton back when Robert Riech was Clinton’s chief economist. But a lot of economic theories have overlap, so that sort of thing can happen.

Exactly what is the damage you expect from running large deficits?

From 1950 to 1980 we ran very small deficit and the debt to GDP burden contracted. Yet economic growth was strong and the secular trend was fro rising interest rates.

Starting in 1980 we started running large structural deficits. Per capita real gdp growth slowed significantly but the secular trend was for sharply falling interest rates. The slower growth may have been due to poor productivity that had little of nothing to do with deficits.

Are you worried that large deficits will crowd out private investment and reduce growth?

Are you worried that large structural deficits will cause a secular rise in interest rates?

Exactly what economic damage do you expect these deficits to create that large structural deficits since 1980 did not create ?

Spencer: I’m worried that we could see a currency crisis.

Am I getting the wrong impression, but it seems a majority of the commentators to this blog are devotees of the “minimal government” concept. Any dollar spent above the “minimal government” amount is necessarily a dollar not spent by free, always much more productive private agents.

Forgetting for a moment that few people can actually agree on what’s minimal, I’d like somebody to explain to me why Europeans manage to spend less and get more health care? Is it just that we are all putzes on this side of the Atlantic?

I also notice that Europeans have higher taxes, or at least I am told they do. And they don’t spend anywhere near what we do on the military either. Why aren’t they rioting in the streets? Am I missing something here? Are they the putzes not us?

Finally, I consider my taxes a bill to be paid. You know, for some service or another. I may think I’m overpaying, but I notice that thought doesn’t pop up when I need or use the service.

I wonder what a Dell would cost if it was made by a non profit?

I remember the Niskanen study, but it seems to have been buried. The question for me is how to raise the price of government, progressive taxe hikes of VAT. That is a difficult question requiring someone like Jim Hamilton to tease out the equilibrium conditions.

Start with this link:

http://www.parapundit.com/archives/003467.html

and drill down from there.

“One of the proponents of the theory that tax cuts increase spending is William Niskanenn, chairman of the very libertarian limited government Cato Institute. Will Wilkinson, also of the Cato Institute, summarizes Niskanen’s argument.

Tax hawks like Grover Norquist, of Americans for Tax Reform, maintain that we should “starve the beast”: create pressure on Congress to reduce spending by cutting the government’s intake of taxes and running up deficits. This is the approach prescribed last year by Milton Friedman and Gary Becker, both Nobel Prize-winning free-market economists, in separate Wall Street Journal op-eds. Friedman predicts that “deficits will be an effective… restraint on the spending propensities of the executive branch and the legislature. The public reaction will make that restraint effective.”

However, economist William Niskanen, chairman of the Cato Institute (also my employer), has presented econometric evidence that federal spending tends to increase when tax revenues decline, flatly contradicting the starve-the-beast theory. Furthermore, according to William Gale and Brennan Kelly of the Brookings Institution, members of Congress who signed the President’s “No New Taxes” pledge were more, not less, likely to vote for spending increases, which is hard to square with the starve-the-beast theory. ”

The dollar fell sharply under the Nixon, Reagan and Bush deficits.

I do not remember republicans complaining about the falling dollar under these regimes.

So why are you worried about it now?

Actually, a weak dollar may be exactly what we need to revive manufacturing and generate solid growth.

For over a decade we have known that social security and health care spending was going to create large budget problems in the future.

The responsible fiscal policy was to run surpluses over the past to prepare for those problems and to be able to use deficit spending in case of a severe recession.

But Republicans did not do that, they supported the deficits creation under Bush.

Now, all of a sudden you have discovered that we have a deficit problem.

I’m sorry, I can not take your crocodile tears seriously now.

You supported fiscal irresponsibility under Bush,

so do not expect me to be fooled by your suddenly getting religion about fiscal responsibility.

JDH

I can’t figure out why it hasn’t happened to Japan already. They seem to defy anything suggested by macro economics or finance.

During the Reagan years it was tax cuts for the rich and rising deficits. The conservatives said that deficits don’t matter. Then during the Clinton years they demanded PayGo and fiscal discipline. Suddenly they again reversed track during the GW Bush years with more tax cuts for the rich and an unnecessary, off-budget war, doubling the debt in just 8 years. Cheney’s famous quote was “Reagan proved that deficits don’t matter.” But with Obama in the White House, the deficit scolds are again demanding PayGo.

Where was JDH’s deficit scolding during the Bush administration? If Bush hadn’t frittered away those trillions in tax cuts and wars in the last few years we wouldn’t be in the difficult position we are now. Where was JDH’s voice then?

Truth be told, conservatives are fine with deficits if it means transforming social security taxes on workers into tax cuts for the rich. Deficits only seem to be a problem when liberals try to reverse the process. Funny how that works.

Huge deficit spending may be just a method to redistribute the wealth … someday if the lenders call in their chips the wealthy could be asked to pony up huge dollars to cover these chips.

Matt Young: Were the last two paragraphs in your post written by Will Wilkinson?

Interesting. Maybe American conseratives just have more trouble than others saying “NO” to special interests. Canada’s “Trust me I’m an economist” Prime Minister Stephen Harper cut the value-added federal sales tax (GST) twice during the height of this last out-of-control commodity-driven bull cycle, and put Canada on the road to a structural deficit.

Spencer: whatever the historical record of say, partisan budget (im)balances, there is still a current question outstanding based on the deficit numbers, which do not lie.

Ex ante, Dr. Hamilton’s final question still stands – we are making a choice today which will necessitate the choice tomorrow between a politically impalatable tax increase or a fiscally impalatable solvency crisis.

Moreover, we have seen individuals, companies, and governments relentlessly back themselves into that kind of dilemma over the past 30 years as Martin Wolf’s chart indicates (http://blogs.ft.com/economistsforum/2009/01/why-dealing-with-the-huge-debt-overhang-is-so-hard/)

So just looking at the trend of increased deficits, why isn’t a currency crisis the most likely outcome? I.e. by this I mean what do you see as likely to change so that the fiscal position improves over a reasonable time horizon?

I also notice that Europeans have higher taxes, or at least I am told they do.

You should look at what else they have. Take a look at “Sweden/the Scandanavial model”, so often invoked by those on the left as an example of how a high-tax, high-social spending model can work out fine.

The rest of the Swedish Model includes privatized operation of public transit (saving 40% on cost!) … privatized, no-monopoly, competitive postal service … 100% voucherized public schools … slashed corporate tax rates (down to 26% top, versus 35% in the US, over-40% including state tax) … private investment accounts in social security … the place has become a veritable CATO front!

Why? Exactly because of the high cost imposed on their society by their very high taxes for social spending. They get that cost back through the efficiencies of privatizing govt services.

After watching Krugman for many years I believe the reason he’s not really upset about all this new red ink is because he’s always believed taxes are going to go way up to cover social spending here, and that it is well and good that they do, and since they are going to this is really no big deal in his world view.

I’ve seen and read Krugman many times saying that our taxes could go up to European levels with no problem. He told the Asia Times “We should be getting 28% of GDP in revenue. We are only collecting 17%” — indicating a preference for the equivalent of a 90% income tax increase. (Although he’s never had the nerve to write that in the New York Times.) Well, if you’re idea is to collect so much more revenue, what’t the big import of a little deficit increase like this?

OTOH, I have not ever heard Krugman say anything like: “We should collect 11 points more in revenue to support Medicare, national health, Social Security and social spending — and in exchange, to make up for the resulting efficiency cost to the economy, we should privatize our transit systems, post office, public schools, other government services generally, and cut corporate taxes too … as per the Swedish model!”

Greg,

“We can borrow at 4-5%, so investing in something that yields a 10% return seems like a no-brainer.”

Let’s invest the whole stimulus money in it, then let’s borrow 400 trillion and invest that, and then let’s invest all of GDP, like bit of icing on top to round out the investment portfolio. I hope you would at least acknowledge that the function is not f(a) = a*1.1 . If it isn’t, we’re just disagreeing over where the curve begins. It also doesn’t answer anything about disciplines and age ranges.

Also, IIRC, isn’t this section of the CBO report based on a study where they:

A) Did highly intensive, interactive levels of teaching. The teachers often taught the kids one on one at home, had extra class hours, etc.

B) Had little to no evidence that the effort expended had long term effects on the children’s education.

I could be mistaken, but I really do think these estimates were based on that study.

“As for your argument that we have saturated that investment opportunity, I don’t see how you can make that argument in the face of data such as only 70% of kids graduating from high school and only 23% of kids graduating from high school showing readiness for college in reading, math, science, and English. The data clearly indicates that we have a long way to go before every child is educated up to their full potential.”

This has nothing to do with it. For the 30% that dropped out entirely, it was because the school had nothing left to teach them? They had utterly exhausted its capabilities? ~77% of the ones that stayed hadn’t, as I’m pretty sure one can reach reading proficiency within the 12y span of primary school. On the other hand, if the high school is both freely available to them all and offers access to more knowledge than they currently possess, how is spending more supposed to make them better educated? They didn’t even avail themselves of what they already had access to. I’ll quote myself and then ask another question:

“[It] is no longer a matter of offering something which people desired but lacked the power to obtain; you are now in a position of trying to make them desire it.”

How much money must one invest to make someone want something that they already know they could have? And the natural follow up: is the answer to that one still a linear function?

GNP,

Yes, a hearsay paraphrase. Three links away from the original research, such is my effort at finding the original report!

I respect JDH, so I take his criticism of Krugman seriously. But it grieves me to see two such good economists disagree when I know this is mostly a matter of relative emphasis on values that I know they both share.

Imbalances are never sustainable. As they say “what goes up, must come down.”

But on the whole I have to agree with Krugman. We are looking at budget figures ten years out, and the biggest problem is actually in the near term. We will run up about $4 trillion in deficits in FR 2009, 2010 and 2011. Nearly half of that has already taken place without incident. (As Brad DeLong put it, “the markets have swallowed it without so much as a burp.”) Despite all the naysayers, there has been no shortage of buyers for the debt.

This is a liquidity trap after all, a once in a lifetime event. We (or at least I) will never see such a crisis again. I’m far more worried about prolonged double digit unemployment than a currency crisis. Based on analysis done by Glenn Rudebusch it is unlikely that the federal funds rate will rise above 0% during each of these three fiscal years.

Thinking further out we see deficits in 2012-2019 in the range of about 3% of GDP. We can easily close this gap with a mere 15% increase in relative tax burden. This is not insurmountable, and what’s more, we already knew this was coming nearly ten years ago, before the profligate years of the preceding administration made this rather more problematic.

> A quarter trillion dollars worth of those loans we’ve guaranteed are currently nonperforming. That’s just Fannie and Freddie

Why bring this up? It’s negligible.

Ok, so $250B of loans are non-performing. Pessimistically, half of them will default. The loans the GSE have are 80% LTV or better so it would be quite extraordinary if they suffered loss rates greater than 50%. So we are down to $62.5B. That’s under .5% of GDP, ie noise.

The GSEs have or soon will have reserves which could cover this. These reserves include the money lent them by the govt (at 10% interest — govt making about $10B/year on interest alone here), but there is absolutely no reason to believe that absent a large collapse (say another 20% leg down) the losses will exceed what the govt has already lent to the GSEs.

On the other hand, the government now owns the GSEs (ie has warrants which could be exercised to get 80% of the stock) and the GSEs own the US prime mortgage market. This is a very profitable market in normal times. Given time, if the government wants these entities on its books, it will make money for taxpayers. Alternatively in time the GSEs can repay the government and then be sold off to private stockholders.

The implicit government guarantee on GSE issued debt is another issue but this guarantee holds equally for all large financial institutions (lesson of this crisis for sure) so that is no reason to shut them down.

Ouch, Prof. Hamilton, I think Prof Krugman just gave you a public beat down:

I’ve got my popcorn; your Economic Manhood demands an answer.

Bumticker, I think you have made the most sense here. Even if we could “get back to where we were”, would we want to? We have always been takers: first the land and its resources, then slaves, then overseas commerce, and finally borrowing. We have always taken more than we have given, and lived high on the surplus. The people that are leading us now are those that are paying off debt and saving. It’s time to grow up or fall flat on our faces.

“We can borrow at 4-5%, so investing in something that yields a 10% return seems like a no-brainer.”

Let’s invest the whole stimulus money in it, then let’s borrow 400 trillion and invest that…

If the subject is the return on federal money used to support education, are we talking about these kinds of results on the money used to help NYC currently pay $19,000 per student with such efficiency as just reported in The New Yorker, and with such accountability as previously reported by this

NYC school teacher?

If so, I’m not so sure about that 10%.

OGT,

Granting license to Krugman to neglect JDH’s point that much of the current debt is not held by the public, is PK suggesting we are in material ways comparable to 1950, such that we can expect explosive (and since unrepeated) growth ahead of us?

Even the most obtuse can see the multitude of ways in which the U.S. is far, far worse off today vis-a-vie 1950.

Re Krugman’s:

~~

… But let’s take a slightly later start date: in 1950, federal debt in the hands of the public was 80 percent of GDP, which is in the ballpark of what were looking at for 2019. By 1960 it was down to 46 percent, and I haven’t heard that anyone considered America a debt-crippled nation when JFK took office …

… How, then, did America pay down its debt? Actually, it didnt: federal debt rose from $219 billion in 1950 to $237 billion in 1960.

~~~~

GDP rose faster than the debt. Duh.

What Krugman obfuscates, ignores, hand-waves away — I’m not sure how to describe it, it’s so blatant — is that ALL projections have debt rocketing up faster than GDP from here on.

Before the recent economic problems, CBO projected primary spending just for Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security would rise by

6 points of GDP — and thus that annual deficits would rise by the same (not counting the rising cost of debt service) — by 2030. Which why both Moodys and S&P projected the credit rating of the US would start falling in 2017, with S&P saying it would be “junk” 2027.

Now Krugman’s is saying: Hey, maybe 2019-2030 will be just like 1950-1960, with GDP rising faster than debt normally, and us not doing anything dramatic to cause it.

“Denial” is not strong enough a word.

“your Economic Manhood demands an answer”

Oh, well, one answer came from Paul Krugman — who used to be one heck of a lot more alarmist about the debt when the other party was in power, even though the debt and deficit projections were much lower then.

In his column “A Fiscal Train Wreck” he wrote that he’d just paid more to lock in a fixed rate mortage because he feared the fiscal wreck coming

would create inflation driving up interest rates within the life of his mortgage.

~~ Krugman, quote ~~

… C.B.O. was projecting a 10-year surplus of $5.6 trillion. Now it projects a 10-year deficit of $1.8 trillion.

And that’s way too optimistic. The Congressional Budget Office operates under ground rules that force it to wear rose-colored lenses … it’s clear that the 10-year deficit will be at least $3 trillion…

[Republicans] say deficits don’t matter. But we’re looking at a fiscal crisis that will drive interest rates sky-high.

A leading economist recently summed up one reason why: “When the government reduces saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises.” Yes, that’s from a textbook by the chief administration economist, Gregory Mankiw.

But what’s really scary, what makes a fixed-rate mortgage seem like such a good idea, is the looming threat to the federal government’s solvency.

That may sound alarmist: right now the deficit, while huge in absolute terms, is only 2, make that 3, O.K., maybe 4 percent of GDP. But that misses the point.

“Think of the federal government as a gigantic insurance company (with a sideline business in national defense and homeland security), which does its accounting on a cash basis, only counting premiums and payouts as they go in and out the door. An insurance company with cash accounting … is an accident waiting to happen.”

So says the Treasury under secretary Peter Fisher; his point is that because of the future liabilities of Social Security and Medicare, the true budget picture is much worse than the conventional deficit numbers suggest….

… the conclusion is inescapable. Without the Bush tax cuts, it would have been difficult to cope with the fiscal implications of an aging population. With those tax cuts, the task is simply impossible. The accident, the fiscal train wreck, is already under way…

I’ve done the math, and reached my own conclusions, and I’ve locked in my rate.

~~~~

Yes, I added the bold to his “the looming threat to the federal government’s solvency”. He wasn’t so sanguine then, eh?

So who to believe? Krugman or Krugman?

James (Hamilton),

Thank you for that post. I’ve been making a similar point in the blogosphere* about the absurd neglect of the context of our projected long-term fiscal imbalance (beyond 10 years) by Krugman and his partisan parrots, including conveniently simple-minded comparisons to the immediate post-WWII years, as they belittle the 10-year growth in our debt-to-GDP and dismiss with ridicule those of us who see it as a problem. (* for example, here http://www.prospect.org/csnc/blogs/beat_the_press_archive?month=08&year=2009&base_name=the_debt_to_gdp_ratio_is_not_a#comment-6287174 )

And I posted the following comment on the NYT site on the thread of that Krugman column today. It appeared, then a few hours later was gone, apparently deleted:

Krugman writes:

what about all that debt we’re incurring? That’s a bad thing, but it’s important to have some perspective.”

I agree with that, except that he should have used “and” instead of “but”, as in “and what reveals it as even worse is when we put it in perspective”. The rest of his column is disingenuous, misleading spin.

What is the proper “perspective”? St art with this CBO projection of their Alternative Fiscal Scenario, which, as awful as it is, actually understates how rapidly our debt-to-GDP ratio would rise to astronomical and unsustainable levels on our current policy course http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/104xx/doc10455/Long-TermOutlook_Testimony.1.1.shtm#1091064 Also take a look at a more plausible projection of how much we will add to our publicly-held debt over the next 10 years ($14 trillion added to our debt, not $9 trillion per official projections that are limited by methodology in the case of CBO and politics in the case of OMB, and thus make some unrealistic policy and budgeting assumptions) http://www.concordcoalition.org/learn/budget/concord-coalition-plausible-baseline . And read at least the Summary and Chapter 1 at http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/102xx/doc10297/06-25-LTBO.pdf

Reading the above information will provide enough of a sense of the scale of the fiscal imbalance over the long term per (roughly) current policies. Now, with that massive scale in mind, along with any reading of expert analysis and commentary outside of highly partisan liberal circles, one will easily see through the slippery, deceptive language Krugman uses when he implies that we will be just fine if we “reform” health care in ways that simply make it “more cost-efficient” — the implication being that there will be no sacrifice in the quality of health care to achieve the enormous savings that would be needed to solve our fiscal imbalance, and even as we expand coverage to 40+ million more people, increasing projected total federal spending on health care net of the level of savings (considered realistic) from cost-control mechanisms in the “reform”. (Let me repeat that again: the “reform” Obama envisions and contained in the bills would increase, not decrease projected federal spending on health care over the short, medium, and even long term)

So what do we have here? Well, Krugman is a smart guy. He knows that the only way we can expand federal coverage to 40+ million more people AND reduce projected long-term federal spending on health care enough to enable us to prevent our growing fiscal imbalance from destroying our economy and inflicting enormous pain in various ways would be for the federal government to cut Medicare and Medicaid so substantially that it would substantially reduce the quality of health care and health outcomes in a variety of ways. There are indeed substantial inefficiencies in our current system, but there simply isn’t enough to solve our fiscal imbalance problem through painless efficiency gains.

Krugman knows there is no free lunch here, let alone a free “All you can eat” buffet, with all gain, no pain. He’s simply, deliberately misleading people because he wants more overall spending for at least the short-term, and he wants (obviously permanent) universal coverage, and he apparently thinks dishonest rhetoric (falsely claiming an all gain, no pain free lunch)is a better way to sell those policies than honest argument, and he has no integrity constraint keeping him from the former.

In Krugman’s rebuttal to Jim’s post (http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/08/28/the-burden-of-debt/), he does a lot of dancing but never addresses the main point, which is that the current context of our projected, unsustainable long-term fiscal imbalance (and the level of sacrifices needed to solve that problem) makes comparison of a given level of 2019 debt-to-GDP to the early post-WWII era not just apples-to-oranges, but apples-to-[fill in here whatever you consider the most un-orange-like object in the world].

And Krugman writes:

the lesson of the 1950s or, if you like, the lesson of Belgium and Italy, which brought their debt-GDP ratios down from early 90s levels is that you need to stabilize debt, not pay it off; economic growth will do the rest. In fact, Id argue, all you really need to do is stabilize debt in real terms.

So where Jim Hamilton has us paying $1 trillion a year to service $9 trillion in debt, I have us paying $225 billion 2.5% real interest on that sum.

Here’s just a handy formula: Assuming (for simplicity) a constant deficit % of GDP and a constant GDP growth rate, debt-to-GDP will eventually stabilize at the ratio of deficit as a % of GDP to % growth of GDP. In other words, divide the former by the latter to get the debt-to-GDP that will be approached and at which it will stabilize. So if we choose (all things considered) a target of a stable debt-to-GDP at 60%, we would achieve that with a combination of deficits at 1.5% of GDP and GDP growth at 2.5% of GDP, or deficits at 3% of GDP and GDP growth at 5%, etc., as long as the ratio stays at 60%.

I don’t know what debt-to-GDP Krugman thinks is acceptable or desirable for the sake of what (supposed) benefits from his preferred policies, nor how he would reconcile the relatively pain-free reductions in projected spending to which he alludes in his first post with the magnitude of reductions we would need to stabilize debt-to-GDP at a given level. He doesn’t address such matters in any substantive way or even at all really, because he’s engaged in pretense — just say that we can solve the problem with pain-free efficiency gains in healthcare and Presto! Long-term fiscal policy problem solved and no one (except maybe a few rich meanies) has to sacrifice at all! I guess “cutting waste in healthcare” is the new “cutting waste, fraud and abuse” to solve all our spending and deficit problems. What a joke.

The real problem with Krugman’s argument — though I generally agree with him — is that our post-WWII prosperity was in major part the result of that military conflict. The war destroyed all of the industrial competition. We (the US) then began to collect rents from the rest of the world.

These rents are steadily diminishing as (for example) China climbs the value chain. They have been eroding for a long time of course. But now that world transportation and communication networks have made it so easy for developing nations to bring their vast labor pools to world markets, the pace of erosion is accelerating.

The US is in a continuing process of *relative* (NOT yet absolute) decline. Our economic ruling class are profiting mightily from the labor arbitrage and simply treating globalization as a big “portfolio rotation”. No sweat, really. What’s the fuss about? Unfortunately for the average American making a living from not-really-so-world class skills, this is a bit like trying to make ends meet in the rich folks’ neighborhood. You might not be *poor* in absolute terms, but you sure feel shabby and deprived in comparison to your wealthy neighbors.

In this we’re not dissimilar to post-WWII Britain. But there’s this important difference: our political culture hesitates to cushion the decline with social spending. Where a Churchill could enthusiastically support the creation of the NHS, an Obama feels he has to apologize — over SIXTY YEARS LATER — for any minor resemblance between his soft-soap reform proposals and the NHS.

Thanks to Jim Glass for pointing (on another blog) to a 2003 column by none other than Mr. Paul Krugman himself saying:

the conclusion is inescapable. Without the Bush tax cuts, it would have been difficult to cope with the fiscal implications of an aging population. With those tax cuts, the task is simply impossible. The accident — the fiscal train wreck — is already under way.

How will the train wreck play itself out? …my prediction is that politicians will eventually be tempted to resolve the crisis the way irresponsible governments usually do: by printing money, both to pay current bills and to inflate away debt.

And as that temptation becomes obvious, interest rates will soar. It won’t happen right away. With the economy stalling and the stock market plunging, short-term rates are probably headed down, not up, in the next few months, and mortgage rates may not have hit bottom yet. But unless we slide into Japanese-style deflation, there are much higher interest rates in our future. http://www.nytimes.com/2003/03/11/opinion/11KRUG.html

And now, with the fiscal outlook even grimmer, Krugman belittles the long-term fiscal imbalance as nothing to worry much about. Simply amazing the extent to which hyperpartisanship can generate bias or (more likely) insincerity.

Thanks again, Jim (Glass). Great catch.

I dont know that it is entirely fair to compare Japans fiscal deficit with the US. A big chunk of the deficit can be attributed to Japans use of general funds to subsidize shortfalls in the off-budget National Pension Plan funding sources (payroll taxes and trust fund reserves).

If you assume that the categories Social Insurance and Public Health Service equate to Social Security and Medicaid in our system, the chart linked below indicates that this accounted for about 42% of the deficit in 2003.

http://www.mof.go.jp/english/budget/pamphlet/cjfc.htm

(You could argue that this distortion is cancelled out by higher level of defense spending in the US but this is assumed to be already understood)

Pages 26-28 here

http://csis.org/files/media/csis/pubs/pension_profile.pdf

detail the recent history of cuts in benefits and increases in payroll taxes Japan has had to make to adjust to their changing demographics.

Although our demographic transition in the US wont be as sharp as Japan experienced, it does give one pause when considering social security goes into net outflow mode in 2016 and Medicare trust fund reserves are depleted in 2017 (http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TRSUM/index.html).

About that $9 trillion in added debt, should be just a blip when 2016 rolls around.

And then we can start on all of the underfunded pensions across the country at the state and local level. I know that in California the vast majority of the large pensions are guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the taxpayers of the state so we can expect to see further tax increases.

Not even Prop 13 can save you:

http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/2074209/embattled_lausd_to_raise_los_angeles.html?cat=8

taxes function to reduce aggregate demand.

in other words, the only reason to raise taxes would be too cool down an overheating economy.

so if we run large deficits now (i prefer a payroll tax holiday so people can make their payments which also happens to fix the banks from the bottom up, and $500 per capita revenue sharing for the states) taxes will only need to go up later if, as i would expect, the economy does so well and unemployment go so low (probably well under 4%) to the point where there’s risk of inflation. In other words, if high deficits today mean a booming economy and the possibility of the need for higher taxes to cool it down, that would be a good thing, not a bad thing.

http://www.moslereconomics.com

In bringing the 1950’s into the discussion, Krugman fails to mention the tax increases during the Korean War (after tax decreases in the immediate aftermath of WWII).

Tax receipts as a percent of GDP went from 14.5% in 1949 all the way up to 19% at the height of the war and averaged 17.8% for the period of 1952-1960.

If Krugman had said the $900 trillion was not that big a deal because we will also increase the tax burden by 23% like we did during the 1950’s (without any impact to GDP or employment) then it would be a fair argument.

It seems odd that he leaves this part out since I cant recall very many articles over the past 9 years where he hasnt mentioned increasing taxes as our only way out of avoiding fiscal catastrophe.

Greg, I think you’re mostly right about education being something good to spend on. But, a couple points.

At best, the CBO gets the sign right and is far off in scale. And I don’t think they consider the cost of debt. An example is CAFE vs gas tax. All they get right is they are both a net cost, they say a gas tax is much less costly. Reality is that they are probably close to identical and CAFE may actually be slightly better because it decreases operating costs producing a stimulus in economic growth.

How gullible! I guess when you want to believe Krugman you fail to see even the obvious flaws in his own black and white arguments. Let’s take one which has been repeated by some of the entries in defense of Krugman.

He writes that “let’s take a slightly later start date: in 1950, federal debt in the hands of the public was 80 percent of GDP, which is in the ballpark of what we’re looking at for 2019. By 1960 it was down to 46 percent–and I haven’t heard that anyone considered America a debt-crippled nation when JFK took office.

“How, then, did America pay down its debt? Actually, it didn’t: federal debt rose from $219 billion in 1950 to $237 billion in 1960. But the economy grew, so the ratio of debt to GDP fell, and everything worked out fiscally.”

Does Krugman really make his case? By showing that the debt actually went up by 8 percent? Duh! Has anyone checked the actual numbers in the revised OMB budget proposals? Let me suggest you go to table S-1 at page 25 of the Mid-Session Review issued on August 25, that you can find at http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/MSR/

There you will see that the White House proposes to increase the debt from 5.8 to 17.5 trillion, almost exactly three times or 200 percent. Like in the 50s, that too would happen in ten years. How can you possibly equate the effects of an 8 percent increase with those of 200 percent or a tripling of the debt? Krugman conveniently ignores other important effects like inflation.

DickF

The road to disaster compared to what?? If you compare the American economy 100 years prior to the New Deal with the period since, I think it’s kind of hard to conclude that the Nineteenth Century was better. The longest depression in our history was in 1893 when we had the small government conservatives long for — no income tax, no regulatory agencies, no federal reserve or FDIC and no social safety net.

In fact, look at this history of recessions/depressions on Wikipedia.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_recessions_in_the_United_States

What you see is that during the reign of the free market in the Nineteenth Century you had very long recessions/depressions. In the Post War/Post New Deal era recessions have been milder and much shorter on average (at least until now)

Now I’m sure that conservatives have some fancy economic theory that just absolutely proves that the prosperity of the United States and the power of its economy in the post war era is just a coincidence that has nothing to do with the huge changes made during the 30s. But liberals have their own theories about why those changes were pivotal and if we’re right, then the conservative agenda, if implemented, will actually run the country right into the ground, to a far greater disaster than if we simply try to manage the crisis as we traditionlly have over the past 60 years.

I like how people keep saying world war II spending was coming to an end. How many bases do we have in Europe still? How many bases did we have in the Pacific after the war? If you count that spending as Cold War spending, then you can add in The Marshall Plan spending. World War II has been done for a while but I am sure there are many ways to count that we are still paying for it, including the many veterans of WWII

The government announced its frightening prediction the federal deficit would total $9 trillion in the next decade, increasing the current $12 trillion debt to $21 trillion in 2019, a 75% debt increase in only 10 years. All experts say the deficit is not sustainable.

The federal debt in 1979 was $800 billion. During the next decade it rose to $2.7 trillion, a 235% increase in only 10 years. As that increase was proportionately three times greater than the increase currently predicted, it might be instructive to see what it did to our economy.

In 1979, GDP was $2.5 trillion. Ten years later, GDP was $5.5 trillion, a 120% increase. That 235% increase in federal public debt resulted in a 120% GDP increase.

To achieve the same debt and GDP growth, today’s federal total public debt would have to increase 235% to $40 trillion by 2019, a total deficit of $28 trillion.

So, please tell me again what historical evidence exists to show the projected deficit is not sustainable.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

rmmadvertising@yahoo.com

The situation of the US vis-a-vis its economic competitors is vastly different now than it was following WWII.

After WWII most of the US trading partners had no factories. All the major european and asian countries had remaining was ragged, war-ravaged economies and depleted populations.

The fact that the US was able to climb out of the WWII debt is probably attributable to being the only intact industrial base at the end.

That is not the case right now. We are in a post-industrial economy and what industry remains is in deep deep trouble. We will never be able to repay this debt in a FIRE economy. Too much of the FED’s liquidity is concentrated in to few hands, and US wages are dropping. This is precisely the opposite of the post-WWII situation.

Jim Glass points out:

“A leading economist recently summed up one reason why: “When the government reduces saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises.” Yes, that’s from a textbook by the chief administration economist, Gregory Mankiw.”

A couple questions. I’ve always wondered about the two sides of bond sales. Is it true that for every dollar spent by government financed by a bond purchase there is a dollar of savings being invested? I’m pretty sure they have to be equal, otherwise the bond isn’t sold (purchased).

So isn’t the disagreement really about the efficacy of the investment? The value of the purchase?

If it’s a poor investment, then the interest on debt becomes burdensome. If not, then heck, leverage up and gain the profit even more!

I suspect that there’s more than a little bias towards capitalism’s ability to lever debt better than governments. No?

This is not a law, by the way, as anyone who’s watched the efficacy of private investment funds lately will acknowledge.

So, shouldn’t the debate center on the probable efficacy of the debt (someone’s invested savings) on future development and revenues as much as on it’s absolute level?

I found Krugman’s “grow our way out” blog a lot like Cheney’s “deficits don’t matter.” Cyclical ones do not, and that’s why I’m less concerned with the numbers from the next 2-3 years. But the overall debt and the $500 billion structural deficit (based on Menzie’s post with the CBO projections of full employment in 2013) are issues that need to be addressed.

This is why adjustments to Medicare and health care costs are appropriate, and why it’s hilarious to see “fiscal conservative” Michael Steele try to score points by saying “We’ll keep Medicare as it is.” The GOP really has no clue on this issue other than clinging to tax cuts, which the last 30 years have proven to be a failed thought.

Sure, growth helps the overall situation, but it shouldn;t be relied on because of the variances of events and human behavior. The structural imbalances are things governments can control, and while it should have been dealt with from the position of strength 8 years ago, it makes it all the more critical to take care of it now.

And it won’t take doubling taxes of any working person to do it. I can think of a lot of cash still going to the Middle Eastern sands that could be saved right now.

A dollar crisis is the nightmate scenario. Given its weight in global finance, that would be a calamity truly comparable to the Great Depression.

But the more inevitable result of using deficit spending to boost consumption will be a deceleration, stagnation or even reversal of growth of real incomes. As amazing as this may be for some of you, this effect does not depend on which party is doing the deficit spending. It truly is exactly the same as when a person consistently consumes more than he earns. Over time, he gets poorer.

Deficit spending to fund sound investments, such as truly valuable infrastructure, can pay off. But take an honest look at where the current deficit spending is going.

Re: Japan, the relevent figure is net debt (after subtracting reserves), which was less than 20% of GDP as recently as the early 90s but is now about 100% of GDP. Real income has been stagnant since the early 80s, and the outlook is grimmer still. The fact that debts are in yen and mostly domestically held while reserves are in foreign currencies shields them from the threat of a currency crisis.

Rodger, you keep posting this same thing on different sites, but ingore every answer you get.

======

Jim Glass points out [Krugman saying]:

… “When the government reduces saving by running a budget deficit, the interest rate rises.” Yes, that’s from a textbook by the chief administration economist, Gregory Mankiw….

… I’ve always wondered about the two sides of bond sales. Is it true that for every dollar spent by government financed by a bond purchase there is a dollar of savings being invested? … So isn’t the disagreement really about the efficacy of the investment?

The explanation as to why a smart guy like Krugman would spew such nonsense is this: For the rhetorical purposes of proponents of currently proposed healthcare “reform”, supposedly harmless efficiency gains in health care are the new “eliminate waste, fraud and abuse” as the panacea of our long-term fiscal imbalance. So anything one can say that in any way makes that premise seem plausible to some people is deemed worth saying, regardless of how absurd. Or, along the same lines, anything that makes those who realize that this “reform” will exacerbate, not mitigate, our long-term fiscal imbalance problem think that this exacerbating factor (the “reform”) is no biggee (because the problem itself is supposedly no biggee) is deemed worth saying.

It’s very hard to believe that Krugman doesn’t know that he’s grossly misleading people and spinning so fast he’s affecting weather patterns.

I like Jim Glass’ idea of looking at the debate between Krugman (2003) and Krugman (2009), when the partisan objective changed. http://www.scrivener.net/2009/08/krugman-versus-krugman-on-deficits-and.html Well done, Jim.

Historical models:

Britain after WWI (cited above).

California, starting a few years ago.

Keep your eyes on California; that’s where the nation is heading.

@Jim Glass,

I noticed you mentioned the Swedish postal market. It’s my understanding that although it is demonopolized, that Posten AB, the government owned postal delivery enterprise, still is responsible for 93% of regular mail delivery. Furthermore it receives a somewhat generous subsidy in order to fulfill its universal service obligation. Are you suggesting that such a system would be an improvement over ours and if so why?

We all know that Krugman could come up with an argument that the sun rises in the west and sets in east if the liberal agenda needed it. And with macroeconomics as your tool, it’s not hard to do that.

The gist of his reply to this post seems to be that we are not paying for 9 Trillion, we are just paying the interest on it, so no big deal.

Plus interest rates are only 3%…a pittance.

Plus we can inflate out of the debt, right?

Another point he may not be aware of is that the duration of treasury debt is now only 4 years. So higher interest rates can quickly increase our debt service cost.

Then the Chinese, OPEC and/or Wall Street may not be happy with the combination of falling dollar, rising inflation and low interest rates that could easily materialize over the next few years.

@Jim Glass,

While I’m waiting to hear about your argument in favor of the Swedish postal system, I’ve been researching some of your other claims about Sweden. Everything so far is coming up rather short.

For example, private investment accounts in social security represent only 2.5% out of the 18.5% of funding. Since the inception of the system in 2001, the average yearly return for savers has been -0.8 per cent. The Premiesparfonden, the default fund in the Swedish premium pension system, and the most “popular” fund, fell by 36.2 per cent in the past year. Authorities are now thankful that the private investment accounts were limited to 2.5% since the blow to retirees would have been much worse, and it would have further destabilized the staggering economy.

It’s true that a significant majority of Swedish public transit uses competitively tendered contracts, and where this has been employed there has been no apparent reduction in service or quality. But the savings are slightly less than 20%, not the 40% you cited, and the system is still massively government subsidized to the tune of about 56% of total cost.

Using competitively tendered contracts may have achieved some measurable gains in efficiency in public transit, but for the most part these free market reforms you’ve cited have been a net loss. Frankly it all just sounds like CATO Institute propaganda to me.

10-year-projected deficit, what a joke… are they counting on not having another recession ever? we had a reccession in the early 90s, another in 2000, another in 2008. How will you pay the “stimulus package” of the next one? lol.

I’m tired of these Partisan attacks on Keynesian policy.

Here’s a new rule, next time you bring up Keynesian policy, also bring up Your Solution to Depression Economics, and how it has No track record of success. Unlike this year with a successful avoidance of a Depression.

Also, these Bank Bailouts were caused by Republicans and Republican sellouts to UBS. Corporate takeover of Democracy. You solve that first. Corporate Deregulation or Unregulation, and Management Capitalism where Short Term Profit came before all else. The Management Paycheck comes first ahead of shareholders, workers and the Nation. That’s the primary problem.

With $27.3 trillion in overall federal backing for the US financial system (via TARP, PPIP, monetization of Frannie debt, commercial paper facility, etc), the distinction between public and private debt is almost meaningless.

DS,

Even with you wikipedia numbers 1893 was not the longest nor the deepest depression. The Great Depression was much longer.

Then any numbers after leaving the gold standard in 1971 are questionable. Inflation distorts measurement under a fiat currency standard. Our economy was declining throughout the 1970s but inflation was roaring.

You need to dig a lot deeper into recessions pre-Federal Reserve to understand.

Cedric Regula writes (regarding Japan’s ultra-low interest rates and big deficits):

“I can’t figure out why it hasn’t happened to Japan already. They seem to defy anything suggested by macro economics or finance.”

Maybe they should try the George Costanza method and do the opposite?

Professor Hamilton: A sovereign currency issuing monopoly with a nonconvertible currency and floating exchange rate can never have a solvency issue. US Govt can never be insolvent in US dollars since they are the monopoly issuer of USD. In fact the currency comes into existence when the govt spends and the currency gets destroyed when the govt taxes. A sovereign currency issuing monopoly with a nonconvertible currency and floating exchange rate need NOT fund their deficits. What is the difference between currency and a bond? A bond is just an interesting paying currency. Bond issuance is just an interest rate maintenance mechanism. The only concern about deficit spending is inflation and with 10% unemployment we are very far away from that concern. In fact basic national accounting says that Govt has to go into deficit to maintaining the Private savings desires. Please refer to the lost decade in Japan and explain why they havent had the insolvency issue that they should have had since the 1990s. Thanks Econorebel

Cedric Regula writes (regarding Japan’s ultra-low interest rates and big deficits):

“I can’t figure out why it hasn’t happened to Japan already. They seem to defy anything suggested by macro economics or finance.”

Thats because Macro economics begins with the wrong premise that the current day fiat currency is convertible to some commodity and Sovereign monopoly currency issuer needs to finance debt and Deposits/Reserves create loans. In reality Loans create deposits. Sovereign monopoly currency issuer does not need to finance deficit. In fact national accounting suggests that Govt NEEDS to go into deficit to FUND the savings desires of the private sector not the other way around. May be one of these days neo-liberal/neo conservative economists will drop their dogma and start learning economics as a science and not as some ideology. Thanks