We know the glass is both half empty and half full. But the real question is whether liquid is being added in or draining out.

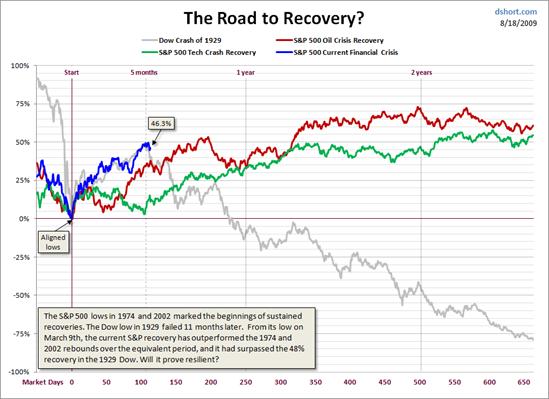

Calculated Risk had been calling attention to Doug Short’s graphical demonstration that the 2007-09 bear stock market was worse than those of 1973 and 2000 and comparable to the first year and a half of the Great Depression.

|

With the remarkable stock-market surge since March, that unfortunate sense of deja vu had seemed to be behind us. But now Short is suggesting that we align the March 2009 bottom with what proved to be a temporary low at the end of 1929, inviting the interpretation that we’ve just turned down on a long, long descent.

|

Among the factors that turned the hoped-for recovery of 1930 into the debacle of the Great Depression were a sharp hike in interest rates in October 1931 and a decline in the overall price level of 10% per year in 1931 and 1932. Whatever else happens, I don’t expect those particular mistakes to be repeated by the Bernanke Fed.

But let us at least agree on this much– stock prices can go down as well as up.

“Among the factors that turned the hoped-for recovery of 1930 into the debacle of the Great Depression were a sharp hike in interest rates in October 1931…”

The current target rate is .25%. If I recall correctly, the Taylor Rule says the current target should be about -6.5%.

“…and a decline in the overall price level of 10% per year in 1931 and 1932.”

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?chart_type=line&s%5B1%5D%5Bid%5D=PPIACO&s%5B1%5D%5Btransformation%5D=pc1

Sorry, professor, I just couldn’t resist.

Only possible if investors feel there is no control over what is happening. Which is not the case.

The initial drop in 1929 was so dramatic as seen from the picture that it overstretched the system, causing a rupture, which destroyed real economy because of lack of motivation to take risks again. The drop was psychologically too much, information too scarce. 2008-2009 drop is peanuts compared to that.

At the risk of sounding like a smartass, I want to pass along a final thought.

As a businessman who is preparing for what will probably be yet another restless night, I can still recall–in detail–some of the economics lectures I attended as a student many decades ago.

Liquidity traps, the profs declared, were a thing of the past. They had been banished–forever–thanks to Keynes and informed monetary policy. It could never, we were told, happen again.

We know how that worked out.

I have a lot of respect for your work, and that of CR, as well as professors Chinn and Thoma. I don’t comment here very much, but follow your work as closely as time allows. Having said that, and with respect, I think you fellows need to get back to your drawing boards. We’re not out of the woods yet–you fellows know that–and some really good ideas would help right now, if for no other reason than to preserve some respect for the economics profession as a whole.

“Among the factors that turned the hoped-for recovery of 1930 into the debacle of the Great Depression were a sharp hike in interest rates in October 1931 and a decline in the overall price level of 10% per year in 1931 and 1932. Whatever else happens, I don’t expect those particular mistakes to be repeated by the Bernanke Fed.”

Do we really know for sure how Bernake and Company would respond? I mean you forget to mention that the October 1930 interest rate hike was in response to an international currency/goal standard crisis. The Fed had no good choices then and if there was a dollar crisis now (which while low in probability is not out of the question), there would be equally few good options.

The fact that interest rates were raised at the beginning of the Depression is not simply A difference between then and now – it is THE difference. The CPI change was positive last year and positive so far this year. We have had the most dramatic global monetary stimulus in history. To claim that the current economic environment and the depression are similar simply indicates a lack of historical knowledge. But yes, stocks can go both up and down.

The initial drop in the fall of 1929 was 48%; the drop from the DOW high of Oct. 10, 2007 to the initial low of Nov. 20,2008 was 47%(by the way, the initial low of 1929 was also on Nov. 20). It seems to me to be a fairly comparable decline.

Given that a whole lot of people bought greatly inflated assets from 2006-2008, their 6% interest rates are really more like 9%. Kind of puts a crimp in the budget. We need to get nominal rates down to ~4% before they can really dig themselves out. When the treasury is pushing 3.75% guaranteed out the door buy the freighter-load, it kind of dries up the market for refi for people who are safe but no longer able to save, invest, or consume.

By initiating a large and poorly structured stimulus before rates got lower, we kept locked in all the risk that made those CDO and MBS so worthless last year and we had to save the banks from.

I don’t see good things in the near future.

“Harvey Firestone, Pres. Firestone Tire & Rubber, states America is on eve of greater prosperity than past 10 years. Expresses belief in Ford’s statement there will soon be work for everybody. Says company has met depression by cutting overhead and lowering prices; plant now running night and day, 6 days a week.” Wall Street Journal, August 19, 1930.

from : http://newsfrom1930.blogspot.com/

worth to read.

Not sure about the deflation. I bought an AV amp for $800. It had just gone on sale from $1000. 56 days later, and well beyond the 30 day price guarantee, the damn thing goes on sale for %550. That is big time deflation. It is galling because I had done my homework.

Given that consumers were over-leveraged in 1930 and capacity utilization had fallen off a cliff, would lower interest rates have made much difference?

Can we agree that in the U.S., and a number of other countries, a credit bubble was building since the mid-1980s, with particularly steep growth 2001-2007? And that production rose to meet the demand created by that bubble?

What difference does it make to Alcoa if interest rates are 4% or 2% when there is huge over-capacity? And consumption isn’t falling because interest rates rose, it’s falling because many households were near insolvent, then saw there assets fall 30%, their income stagnate or fall, and there access to credit contract.

I think we need a new mantra, a la the Clintonista’s:

It’s the deleveraging, dummies.

The lesson I take from the graphs is that the harder and faster we prop things up, the worse they are for a longer period of time.

Because the Asian mercantilists have insisted on running huge trade surpluses, the status quo ante depended on the US being willing to take on ever more debt to them.

Now the means for increasing the debt load of US consumers have broken down, because consumers willing and able to repay don’t want any more debt (and are increasingly thin on the ground), and the mechanisms for lending to those unwilling or unable to repay have in particular broken down.

Moreover, as Americans come to realize they are must pay down debt and increase saving because neither stock market nor real estate appreciation is going to fund their retirements, they have increased their purchases of US Treasuries so greatly that the mechanisms for recycling the Asian surpluses back through US government borrowing seem also to be breaking down.

So there is no way that the economy will return to the status quo ante of consumption at 70+% of GDP. This means there is going to be massive dislocation in all sectors that must shrink as a result.

So let’s be agnostic;

1) Let’s take all periods in which the S&P500 rises by 40% or more in 100 days. What’s the historical distribution of realized returns over the following 500 days?

2) Now let’s restrict our attention to those of the above cases in which the starting point is at least 40% the maximum value over the preceding 5 years. Again, what does the historical distribution look like?

Banks leveraged up day by day week by week year by year for ten or twenty years. Sending false signals to the real economy, creating false volume on the exchanges, creating false price levels and price points on goods of every class and level. Bush removed the last bulwark against banks leveraging up massively. When the banks went from ten to one to 70 or 97 to one against reserves a shadow banking system, a fake currency was created so to speak, a virtual money, we were all paid in real money, and that pay did not rise very fast, but the prices of all the fake economy, housing prices, luxury items etc, for example a Prada belt costing 950 that costs ten dollars to make and ship and market. Now we reap what the banks sewed.

I don’t think that any analysis that tries to find out what is coming with respect to US- and world economy is any worth it, if it doesn’t take it into consideration the biggest debt bubble maybe in history, which we can diagnose currently. The total US credit market debt to US GDP ratio was at a new record of about 375% as of Q1 2009. This is far higher than the debt bubble before and during the Great Depression, which deflated back then. What implications does the current debt bubble and it’s deflation that is probably coming have for the future? Isn’t this a or even the major issue for the world economy (and therefore also for the markets) in the next years?

rc

“Among the factors that turned the hoped-for recovery of 1930 into the debacle of the Great Depression were a sharp hike in interest rates in October 1931…”

I am increasingly dumbfounded how everybody seems to believe the FED can continue to suppress interest rates at will, while the government is running ever bigger deficits! And to top it off the implied assumption that in 1931 it was a deliberate, completely unforced rate hike!!

Nowadays at some point the bond markets will leave the FED no choice than to increase rates. That’s when things will turn REALLY ugly.

The reason we will not experience a deflationary spiral akin to the depression is because Bernanke has made it profoundly clear that the Fed has both the tools and the motivation to increase prices in nominal terms.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/BOARDDOCS/SPEECHES/2002/20021121/default.htm

Yes the consumer is over-leveraged just as in the depression, but overleveraged in an inflationary environment is vastly preferable to being overleveraged in a deflationary environment – and no argument can be made that our current environment is more deflationary than the depression at this point.

Two points :

1) A repeat of the GD will not happen, as in that case, the whole world was in depression, whereas now, emerging markets have bounced back enough to keep world GDP positive even if the US has negative growth.

2) Even when measured against the 1975 and 2003 rallies, the current level is appearing to be a top, and no one has much upside from being long right now. Arguing about the downside or lack thereof is one thing. But there appears to be little scope of another 20% rise from here, so why be long?

CalculatedRisk is a great blog, but comparing index charts is magical thinking. If you look hard enough, you can find a comparable historical series from any trading index, from tulip bulbs to pork bellies.

The shape of the curve is a red herring. It’s the price level, the YIELD AT CURRENT PRICES, that shows the danger.

Earnings yield on the S&P is now around double the 1970s low, just before the last bull market began. So price levels have fallen, but are not especially low compared to earnings, by historical standards.

Moreover, the 1970s low came at a time when interest rates were high, and had room to fall for decades, making equities ever more attractive. The opposite is true now: interest rates are almost certain to rise over the next decade, putting ever-increasing pressure on equities, whose prices must fall for their risk-adjusted earnings yield to compete with rising yields in other asset classes.

And this is before considering inflation, which will squeeze the real yield of all assets.

SvN asked the right questions :

1) Let’s take all periods in which the S&P500 rises by 40% or more in 100 days. What’s the historical distribution of realized returns over the following 500 days?

Answer : Usually less than a 10% rise.

2) Now let’s restrict our attention to those of the above cases in which the starting point is at least 40% the maximum value over the preceding 5 years. Again, what does the historical distribution look like?

Well, note that the 2007 top was a weak top (i.e. not much higher than 7 years earlier), and that the 1929 top was a very strong top.

The closest analogy to the GD would be to compare the Nasdaq peak in March 2000, and project out the next 9.5 years. That is where the accurate comparison lies.

Per William Mitchell’s comment…

So you are arguing that equities are an unattractive asset class given coming inflation and higher interest rates. So given coming inflation, what should you own now? Cash yielding .5%? Treasuries yielding 3.5%? Or the S&P 500 with a yield of 2.66% – a real yield? Unless you think inflation will run less than 1% annually over the next ten years it’s hard to make the case against stocks. You may argue that stocks will go lower in the short term, but in that case you are relying on your market timing ability and not on the long term fundamental outlook for asset classes.

National Bureau

of Economic Research

BULLETIN 50

APRIL 18, 1934

A NON.PROFIT MEMBERSHiP CORPORATION FOR IMPARTIAL STUDiES IN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL

BROADWAY, NEW YORK

Recent Corporate Profits in the United States

Copyright 1934, National Bureau of Economic Re.rcarch, Inc.

SOLOMON FABRICANT

AGGREGATE NET INCOME OF ALL CORPORATIONS IN

THE UNITED STATES, 1919-1932

(Excluding tax-exempt corporations and life insurance companies)

(In millions of dollars)

Aggregate net income Income- and Aggregate net income

Year before payment of

income taxes and

dividends1

profits- taxes

paid2

after payment of income

taxes but before

payment of dividends

1919 9,320 2,410 6,910

1920 5,920 1,640 4,280

1921 640 710 —70

1922 5,070 770 4,300

1923 6,640 – 920 5,720

2924 5,740 870 4,870

1925 7,990 1,160 6,830

1926 7,840 1,210 6,630

1927 6,840 1,110 5,730

. 1928 8,670 1,170 7,500

1929 9,130 1,180 7,950

1930 1,960 700 1,260

1931 —2,850 390 —3,240

1932 —4,600 330 —4,930

* Preliminary estimates.

Statutory net income plus tax-exempt interest, adjusted to secure

Anyone knowing which year we are, when backscaling the comparison?

Anyone knowing in these years the US was a net exporter of capital and oil?

Industrial component was a large component of GDP

I like graphic representation they drive a Pavlovian reflex.

@Garrett:

“The reason we will not experience a deflationary spiral akin to the depression is because Bernanke has made it profoundly clear that the Fed has both the tools and the motivation to increase prices in nominal terms.”

So he thinks. However, Bernanke’s thinking like the one of neo-classical economists generally, is based on the money-multiplier model, which has been empirically falsified. They just have notoriously ignored this. See Steve Keen’s essay “The Roving Cavaliers of Credit”, http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/2009/01/31/therovingcavaliersofcredit

Even if the money-multiplier model were to reflect reality correctly, the Fed would have to increase base money 25 times compared to pre-intervention level. The interventions so far have barely had an effect.

rc

GK: “The closest analogy to the GD would be to compare the Nasdaq peak in March 2000, and project out the next 9.5 years. That is where the accurate comparison lies.”

So, what we saw between 2000 and 2008 was a massive deleveraging of the economy, just like the 1930s?

um, right…

Warren Buffett has kindly decided to weigh in on our inflation/deflation debate today.

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/08/19/opinion/19buffett.html?pagewanted=2&hp

GK said: “…The closest analogy to the GD would be to compare the Nasdaq peak in March 2000, and project out the next 9.5 years. That is where the accurate comparison lies.”

For anyone who was around for the tech bust, this is precisely the same comparison bears used at the time (2001) to “prove” that the U.S. was headed for either: A) A new Great Depression or B) a “Lost Decade” like Japan had. The near-vertical rise and subsequent collapse of the Nasdaq Composite was (allegedly) our generation’s version of the 1929 crash of the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the collapse of the Nikkei Average.

Sebastian

“So let’s be agnostic; Let’s take all periods in which the S&P500 rises by 40% or more in 100 days…”

I believe projections based on past averages is a big factor behind present troubles. You are trying to apply “what usually happens” logic to processes that are by definition irregular. Statistics said buy and hold after the SP500 dropped 10% to 1200.

jm, I really like your thinking.

If Asian mercantalism breaks down, they could always turn to internal growth. The Chinese could easily be like America was during the 19th Century, developing itself not through exports, but exclusively through internal growth. An appreciating currency would actually help in that regard, as it would make the average Chinese person much wealthier.

Professor, until we bring down household debt to income, this is easily a replay — amped up — of The Lesser Depression.

Unfortunately, it looks like things will take a turn for the worse.

Weimar Germany had inflation, then hyperinflation, over ’19-’23. The cause of such was deficit spending at the federal level, accompanied by money printing by the central bank.

Germany’s federal deficit in ’18 was 33%. In ’19, it moved to 70%.

Our ’09 federal deficit YTD is 43%.

In June, the Chinese and Russians were net sellers of our Treasury notes. As soon as the Japanese and Brits join them, the game is over.

Look at the CPI; since January, the index has been moving up, again. The liquidity is working its way back into prices.

Inflation and hyperinflation, combined with depression, is coming our way.

No (serious) deflation, no Great Depression, sorry. 1929-1933 was under a deflating gold standard.

Japan’s “Lost Decade” is much more likely though.

“I am increasingly dumbfounded how everybody seems to believe the FED can continue to suppress interest rates at will, while the government is running ever bigger deficits! And to top it off the implied assumption that in 1931 it was a deliberate, completely unforced rate hike!!

Nowadays at some point the bond markets will leave the FED no choice than to increase rates. That’s when things will turn REALLY ugly.”

The belief in the Fed’s omnipotence and its ability to easily manipulate the economy like the gears of a machine is born of the 25-year “Great Moderation.” Witness the poster Garrett claiming that a speech delivered by some wonky policymaker in 2002 is sufficient to levitate inflation expectations and asset values in the tens of trillions of dollars.

To anyone who cares to actually look at the data it is painfully obvious that the market, not the Fed, controls interest rates, even on the very short end of the curve. 3-month T-bill yields have consistently LED, not followed, the Fed’s decisions on short-term rates. (http://www.elliottwave.com/freeupdates/archives/2009/08/18/Interest-Rates-Think-Central-Banks-in-Control-Think-Again.aspx) This does not necessarily mean that higher short-term rates are in our future, but it does mean that what Bernanke & Co. want matter much less than Mr. Hamilton presumes it does.

Modern economists who carp that the depression of the 30s was caused by “bleedingly obvious” policy blunders are betraying immense hubris about their own ability to diagnose, and prescribe & implement the correct remedies for, major structural shocks in the economy (such as, say, the revulsion against debt which is only JUST getting started in the U.S. and around the world).

Sorry jg, but no “inflation” is coming. Let it go and move on. You also use CPI which is a poor measure of inflation.

Right now we have deflation and it shows. We will probably be having deflation for a long while.

Those who think it was a decline in prices, strangly called deflation need to look at the decline in 1920-21 and remember that when the FED and Treasury did nothing it was over in less than a year. Look at the chart “mp” referenced. Also note that tax rates were reduced after 1920-21, they were increased by Hoover especially in 1931, then after a short bout with foolish austarity they were reduced after WWII. Everytime there was an economic decline and tax rates were cut we saw a recovery. Tax increases made things worse. Monetary stimulus did nothing at all.

Graphite said: “…Witness the poster Garrett claiming that a speech delivered by some wonky policymaker in 2002 is sufficient to levitate inflation expectations and asset values in the tens of trillions of dollars.”

It’s funny that you mention policymaker jawboning, because I’ve been theorizing that Paulsen’s and Bernanke’s unreasoning fear contributed to (triggered?) the worst part of last year’s financial crisis. Especially now that we can see where we stand just about a year farther on.

Remember when those two characters went to Congress in September, 2008 and confronted them with “You have to give us $750 billion immediately or the entire global financial system is going to collapse”? The bond and stock market panic happened *after* that. Their “sum of all fears” mindset went viral and that became the benchmark for the worst-case scenario that investors had to discount.

And the reason I characterize them as “panicked” instead of simply being messengers accurately conveying the bad news?

First, how would these guys really know *what* would happen? If they had been that omniscient, wouldn’t we have avoided all this unpleasantness in the first place?:)

And what about their Keynesian solution of flooding the economy with liquidity? I’m no economist but wouldn’t it take months, quarters, or even years for such a massive amount of money to really make itself felt? There’s some evidence that the recession may have already hit a trough, far too soon for the Keynesians to claim that it was them what “saved” us from a Depression. (Paul Krugman should have known this, surely?)

JMO, but I think the economy simply did what it was always going to and the Fed is just a lead-foot with the gas.

Sebastian

These simplistic comparisons to GD1 make rather more sense to me than econometric estimates based on experience in other post-war recessions. The current situation is more nearly comparable (the large debt overhang) to GD1 than the other recessions.

As to the Fed’s better knowledge, a new wave may yet appear and make obvious the true state of the financial institutions (with their large overhang of existing losses) and require new bailouts that will threaten to sink the Treasury. At that point, we may rediscover how it is possible that the Fed could raise interest rates when the economy is in dire straits. Just as we rediscovered how liquidity traps can happen.

A lot also depends on whether or not the government follows the same path they did in the 30s:

– creating temporary jobs that will end (and thus a 2nd dip in employment)

– passing legislation and/or taxes that worked against any ability for the economy to correct itself naturally.

kurt, don’t forget the resurgence in protectionism as seen in the “buy American” provisions of the stimulus and the central banks’ desperate attempts to beggar their neighbors by weakening their own currencies.

Sebastian,

I tend to think that the “Paulson & Bernanke caused the panic” idea incorrectly attributes economic power and influence to policymakers in the same way that “the Fed will save us from a second Great Depression” does. There’s plenty of evidence that there was a genuine banking panic building in the fall last year (as seen in, e.g., the huge withdrawals from money market funds that were taking place after the Reserve Fund broke the buck). And it’s perfectly reasonable to believe that such a panic WOULD have occured after roughly 70 years of the government and Fed suppressing banking panics and shoving credit into the system, which built leverage to historically unprecedented and totally unsustainable levels.

It’s not 1929, because the banking system did not fail.

Here in Houston, the recession seems well over. I could barely get a flight down, had to beg for a rental car, and the hotels are gouging me. This is a huge change from just a couple of months ago. We are going up hard on the “V”.

More evidence? US petroleum products inventories are down 11 million barrels in a week. I monitor this statistic every week, and the biggest weekly change I can recall is perhaps 5 million barrels. Normal is 2-3 milllion barrels. 11 million barrels is huge.

So, strong “V” recovery, straight into the next oil shock. That’s my call.

Why don’t we discuss Rescission?

There seems to be No National Coverage of Rescission.

Some important questions:

1) What is total number of Rescission’s in 2008

2) What percentage of policies with health care coverage in the 20% of costs are Rescissioned?

3) Why isn’t there a FRAUD investigation of the insurance industry.

to Steve Kopits

“So, strong “V” recovery, straight into the next oil shock. That’s my call.”

I agree. Economy ( or rather, human psychology) has become rather volatile after huge Lehman panic and instant real time information dissemination via Internet that feeds the animal spirits. So it likely that huge up and down swings will continue with relatively big amplitude and relatively short periodicity ( less then 1-2 years) – until they get so fast that governments are not able to coordinate actions anymore…

But what about inflation?

Garret, it depends entirely on which prices are going up, which are going down, and who’s overleveraged. Right now we don’t have inflation, but prices that matter are sticky, rising, or not falling enough. Two in particular are food and interest rates for existing debt.

I wish more people, including Mr. Bernanke, spent more time actually looking into the great depression from a chronological perspective (I know hes suppose to be the expert, but I still wish I had more faith in his understanding of the series of events that actually occurred). The problem too many people have is that they talk about the October ’29 crash and then move right to bread lines in 1933-34. The GD was caused by a series of events that lead to a complete meltdown of the US financial system. In comparison terms we’re in the summer or fall of 1930. Unemployment and economic contraction are comparable. The economy is in pretty bad shape. The question is what will the next event be and will we be able to navigate?

In the fall of 1930, the US had its first banking crisis (before the FED had raised rates in 1931). In a great paper written by Gary Richardson in 2006, (http://www.econ.berkeley.edu/~eichengr/corresp_richardson_9-15-06.pdf) you will find out that the leading problem in the early 1930s was a flawed payments system. Successive shocks to this system lead to its collapse and the final meltdown of the US financial system.

While the payments system we have today isn’t prone to the flaws of the 1930’s, our economy is very weak and the banks are lying about how bad there balance sheets really are. What other crisis tips the banks back into failure and financial panic? That question is yet to be answered. How and can the FED stop the next panic is also yet to be answered. This ride is not over yet.

Steve Koptis might be right, but I think incomes need to rise and consumer prices need to fall relative to interest expense before a real recovery can take place. Anything else will be temporary and with more pain later. I also think how this winter is weather wise will be important. If we have another bad winter, especially globally, I think it will proclude that a steep V regardless of how much fiscal stimulus we do.

Do we really know for sure how Bernake and Company would respond? I mean you forget to mention that the October 1930 interest rate hike was in response to an international currency/goal standard crisis. The Fed had no good choices then and if there was a dollar crisis now (which while low in probability is not out of the question), there would be equally few good options.

The option of simply letting the dollar fall and have a bit of inflation would be pretty reasonable. Inflation is treated as the huge bugaboo, but currently a bit of inflation would be preferable. What we have is a massive debt crisis, and inflation decays debt, which is exactly what is needed to work balances out.

Currently the markets have absolutely no short or medium term inflation expectations. The TIPS spread is still well under 1%, and has started dipping lower again, after rising from near zero in the second quarter.

In spite of base expansions and low interest rates, money is still fairly tight , partly because of the fed’s current policy of paying interest on excess reserves. That means a fair amount of the expanded monetary base is sitting in vaults at the fed, rather than out inflating prices and the economy. Scott Sumner thinks they should scrap that policy and even introduce a charge. Bernanke seems to like the banks holding excess reserves as a hedge against overleveraging again.

Note that nominal interest rates were very low in 1930 also, but retrospectively it is clear that money was, in fact, *very* tight due to loss of velocity combined with a tight gold standard.

Right now, our strong dollar is actually the problem, keeping the fed from putting too much into the economy without risking further overleveraging, and keeping debt balances high. a spot of 4-5% inflation would work those debt balances out over a few years of sluggish real growth with minimal pain. The problem is, dropping 10% of real capacity in a 0% inflation environment involves companies going bust, people defaulting on debt and mass layoffs into a weak employment market thus causing further defaults on mortgages and consumer loans, and then the bankruptcies and defaults just cause more economic weakness.

Dropping 10% capacity in a 5% inflation environment may just involve hiring freezes, stagnant wages, occasional layoff, financial losses that don’t bankrupt companies, etc. All stuff that is bad, but doesn’t tend to spread contamination further because it doesn’t cause enough defaults to have a chain reaction.

You don’t want inflation in a booming economy and you don’t want highly unpredictable or hyperinflation, but in a struggling economy, inflation is a *good* thing.

I find the assumption that inflation will always shrinks debt very disconcerting. It will only do so if it falls on the assets backing the debt and income and not simply drive up other prices.

If, as James Hamilton analogizes, the economy were a glass, the answer to the question, “…whether liquid is being added in or draining out” cannot find a consensus on this blog. Maybe its a wash.

Nobody on here seems to wonder where the jobs to address unemployment are going to appear from.

There is some very articulate, high level, theoretical argument and confusion going on here, but let me ask. In economics, do jobs just sort of pop up on some kind of cue? Jobs and then income are the leaders where I am.

Tell you what. I think if the lenders went back to lending we’d have a real good start on ending this recession and then we could figure out what problems globalization create and work on a solution so we don’t wander into the abyss again.

Not one word here about Great Britain going off the gold bullion standard in the fall of 1931!

Really!

The Fed kept interest rates low prior to support a Pound Stirling rate of over $4.59 to the Pound, until the end of autumm of 1929. When the peg finally finished with the British economy and the British government went off gold, interest rates skyrocketed as everyone wanted buy gold with incredible shrinking pounds. Pound, dollar and bullion were the reserve currencies in 1931.

The Fed was trying to defend its gold reserves in 1931.

Now, it is dollar, yen and Euro. No gold but a flow of credit flushing hither then thither. All are @ ZIRP and with much finger pointing.

The difference between now and 1931 (or 1831 for that matter) is the underlying problem is the cost of crude and impact on the overall economy. $70 crude is too expensive, businesses cannot make a profit buying it in any form unless they pay slave wages. This they do in China and India. China and India have temporary ‘growth’ while the US and Eurozone do not.

GDP deflation marches in lockstep with the decline in crude output. As the output of crude declines further, GDP will also decline further. This is worldwide; some countries will successfully steal some growth from their neighbors and some will have their growth ‘stolen’ by financial nonsense or currency games, but this is not sustainable.

Neither is our fuel use sustainable! We are long past peak oil. This can be seen by the inability of money investment to increase the output of oil.

Austerity – of a kind that is hard to imagine for most people – is coming and cannot be stopped.

Time to stick a fork in it; the world economy is done!

I find the assumption that inflation will always shrinks debt very disconcerting. It will only do so if it falls on the assets backing the debt and income and not simply drive up other prices.

If the debt is denominated in the currency being debased, then inflation will reduce the debtload relative to GDP, versus an economy with equivalent real growth and less or no inflation. How could it be otherwise?

Inflation only hurts debt resolution if too much of your debt is denominated in other currencies or in commodities or real assets.

So how and when will the Fed recall all the liquidity it created without creating negative effects? If the general economy started to revive, pulling that money back will hurt and retard it.

If they don’t reduce the money supply, inflation will result, would it not?

As someone on the front lines of the economy, I have to ask, just what factors or sectors will increase our prosperity and gets us growing again?

I see few candidates and a lot of dragging sectors.

Actually, a lot of people think a dollar crisis is overdue to hit. I think we just have to hope that we’re out of the woods of near-recession before the dollar crisis hits, or the Fed will have zero options left and we will see a repeat of 1930.

Now, as for sectors which will revive the economy: renewable energy and rail transportation are the only two really plausible candidates I can see. To a lesser extent, computing, but it’s going in the direction of being in-house and not-for-profit, so don’t invest in computing companies.

Mr. Nerode,

I suggest you look back at Professor Hamilton’s post on “Green Jobs; Brown Economy” to see a good argument why renewable energy efforts will hurt rather than stimulate the economy.

Rail transportation – with current rails and rolling stock or with new, expanded capital investments? Unless there was some big productivity improvements to be had (there are bottlenecks to be removed), this is an expense and will lag recovery, not lead it.