William Sterling of Trilogy Global Advisors has an interesting new paper on the abrupt changes in financial markets subsequent to Lehman’s bankruptcy on September 15, 2008.

Sterling’s paper is in part a response to earlier analyses by John Taylor (2008, 2009) and

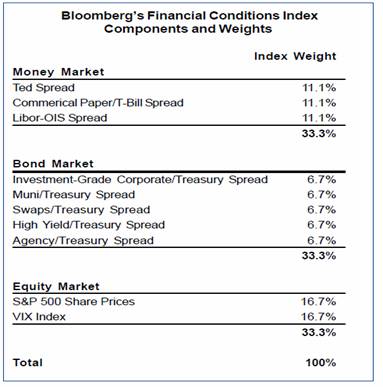

John Cochrane and Luigi Zingales who noted that the spread between the LIBOR interest rate (London Interbank Offered Rate) and the OIS (Overnight Index Swap) rose only gradually following the Lehman bankruptcy, leading these scholars to see Lehman as just one of many relevant developments at the time. But Sterling questions the meaningfulness of the LIBOR or OIS indicators during these weeks given that markets seized up and little trading activity was occurring in these instruments. Sterling instead proposes to take a look at Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index, which Bloomberg launched in August 2008. The index is based in part on the observations by Rick Mishkin on some of the regularities observed in earlier historical financial crises. The components of the Bloomberg index are as follows:

|

Here’s Sterling’s graph of the behavior of the Bloomberg index, in which the remarkable character of events following September 12 is pretty striking.

|

Even if the Lehman failure is agreed to as a definitive event, it is not clear to me that this establishes that all would have been fine if the Fed had only bailed out Lehman as they had Bear Stearns and AIG before. That question is inherently and unavoidably counterfactual. We can’t know– and decision-makers at the time couldn’t know– which domino might have been next to fall had this one been propped up.

But I think it is fair to conclude that the middle of September of 2008 marked a clear turning point in the unfortunate sequence of events through which we have recently come.

When a system is unstable, any number of small events can knock it over. If one disruptive event doesn’t do the job, another will come along shortly and take things down. Therefore it is not useful to ask if a particular event did the system in. It is much more interesting to ask if the system is fundamentally unstable.

An excellent analogy I’ve heard explained to me is as follow. Try standing a pen up on the tip of your finger. Eventually, the pen will tip over. We can attribute the pen tipping over to many events (e.g. shaky finger, breathing too hard, people walking by, etc.). We can even contemplate what if scenario where some of these distruptive events were prevented. However, in the end, even if we could prevent some disruptive events, something else will come along to knock the pen over. The main reason the pen tip over is because it is in a unstable state. Everything else are merely triggering events.

Clear pulse character with exponential decay. I wonder why no one ever has modelled ( or has) stock market etc as linear resonant systems with certain parameters L,R,C. R*L would determine the rise of pulse (drop in chart), C*R- exponential tail ( rise in chart) , R would ensure that system is over damped and generally stable.

Obviously, in financial markets, as seen also from this Bloomberg graph, L (information inductance) is smaller than C ( information capacitance) and R is big enough.

The existance of L and C means there is some resonance frequency, or periodicity of price amplitude (value) (or change speed) in the financial system of the USA, that does not change very fast over years, as its of fundamental, human network and information exchange nature.

The content of the ideas of information inductance, capacitance and resistance could be attributed perhaps to :

Inductance- reaction speed to information events outside market, kind of inflow of information currents

Capacitance- reaction speed to price events, so market changes, kind of changes in information voltage

Resistance- delay between these information events and decision, phase shift between information currents and voltage (price).

In essence, financial and any markets are exchange of information via money values , so that information flows to low information voltage regions with money returning from them.

Thus, the information current flow to these low information voltage regions is inverse to money flow from these regions to high information voltage regions, and is measured as USD/s^2 where s^2 is time squared-its a derivative of velocity of money in a certain information current loop.

So, I info = [USD/s^2]

U info = USD

R info – s^2 (time squared) .

Then, to be consistent:

Q info (information charge) = USD/s =money velocity

C info = Q/U = [1/s]

And L info = [1/s] to have sqrt(1/LC) = w resonance

Information POWER

P info = I*U = [USD^2/s^2] = money velocity squared , does not depend on sign

Information Energy:

E info = Power*time = [USD^2/s]

Information ACTION = [USD^2]

And so on, many analogies with physics can be found and utilized.

As noted in this Wall Street Journal article, we once again ignore Ludwig von Mises at our peril. If you are a serious student of economics you must understand Mises as well as you understand Keynes.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704471504574443600711779692.html

All this time to gather up some 20/20 hindsight in pretty chart form, and the chart still doesn’t reach back further than 2007…..still not getting it, are we?

Jim, Thanks for the nice summary of my paper. I cannot disagree with you when you say “it is not clear to me that this establishes that all would have been fine if the Fed had only bailed out Lehman.’ As you indicate, that type of statement is not falsifiable and therefore is not one that could be addressed by the scientific method.

That said, it strikes me that the Bloomberg data still permits some interesting questions to be asked such as “is it highly risky to let systemically important financial institutions fail?”

One way to look at the Bloomberg data is in terms of a simple contingency table. Suppose you define a financial and economic catastrophe as a 4 standard deviation worsening of financial conditions in one quarter. We now have 74 quarters of observations on the Bloomberg Index and in only one of those quarters did we experience a catastrophic worsening of financial conditions. That happened to be the only quarter that policymakers let a systemically important financial institution fail.

Correlation is not causation, but any statistical measure of association would suggest there is something worth considering here.

Very rich contributions of all parties,as consigned by the Ny Fed grimoire of events.

Would it be wrong to read a tentitative and natural rebasing of the Bloomberg Financial conditions index as of 1998 till 2004.The same events being contradicted by forcefull and may be inapropriate financial steps throughout this time frame,an explanation for today s ongoing and aggravated imbalances?

Agree that the Bloomberg measure is more indicative of conditions following the Leh,man failure. Economic and financial devastation would have been unleashed if Bear jhad gone into bankruptcy, Merrill, or even more so AIG. The lesson is that some institutions are too big to fail — even if they deserve to fail. It was an error to let Lehman or any other large financial institution go. What is needed to prevent this in the future is far better regulation and oversight than what we’ve seen. Regulation has been a joke. What would our country look like if we largely eliminated the all police forces? What has happened in financial markets is bad behavior that has happened because it can. We need to make it more difficut for Wall Street to mess up the rest of the country.

Joseph Tibman,

Author, “The Murder of Lehman Brothers, An Insider’s Look at the Global Meltdown”

lehmanbook.blogspot.com

Non-economist here. I notice that the Bloomberg index was negative from 1998 onward through 2005. ’98 is well before the accepted onset of the Tech Bubble burst and 2005 well past the onset of recovery. Would some economist care to comment, please?

Significant percentages of the Bloomberg index are dominated by government/fed purchases. Most of the others are affected by guarantees and liquidity injections.

These indices have the predictive value of soviet era economic reports.

i really enjoyed reading the report on the consequences of Lehman failure. although I am not a major statistician myself, and some of the terms threw me off, i got the gist of the paper. the index at the moment sheds a light on financial conditions. however, i do agree with the paper’s conclusion that the inclusion of some factors (LIBOR-OIS) can be ommitted, and replaced perhaps with CDS indices, municipal bond insurance (forgot the name of the index) indices, which can better gauge the risk factor inherent in the financial markets. all in all, good job.

even though we are talking retrospectively here, it is important to understand where we came from, to understand (and better equip ourselves) where we are going.

cheerz

KFritz, It was pretty much one thing after another that kept the Bloomberg Index down in the 1998-2003 period. The Fed started raising interest rates in mid-1997 but then the Asian financial crisis started and created a lot of market volatility and financial strains. That turbulence and downward pressure on financial conditions forced the Fed to go on hold for a while. Then in 1998 Russia defaulted on its debt (due in part to low commodity prices created by the Asian crisis) and in August 1998 the LTCM hedge fund (“When Genius Failed”) imploded and created the risk of a systemic meltdown. The third quarter of 1998 was the second most negative quarter in the entire period in terms of a decline in the Bloomberg index. In response to the Russian debt/LTCM crisis the Fed cut rates and financial conditions began to improve in 1999, but a combination of rising oil prices and excess demand associated with the tech boom prompted Fed tightening in 2000. That triggered the “tech wreck” recession of 2001, followed by highly volatile markets associated with 9/11, bankruptcies of Enron, WorldCom, Global Crossing, etc. No wonder Alan Greenspan’s recent book was called The Age of Turbulence. A key point from all of this is that even though economics textbooks often talk about Fed policy as being all about setting “the interest rate” (r), their policy actually has to work through money, bond and credit markets that can have a mind of their own. I hope this helps.

It’s pretty clear that Lehman blew the doors off the hinges. However, it is also clear that there were a number of other problems in the financal system. My personal sense is that employment is higher by perhaps a percent of so due to Lehman.

I personally subscribe to the ‘repository of rights’ model, in which big banks contain not only their own property rights (equity values), but are repositories of client and partner property rights–mortgages, time deposits, demand deposits, etc.– in a more general sense. Therefore, a big bank failure creates externalities because it takes down not only investors in the given institution, but also those who rights are managed by the institution, and possibly creating uncertainty about the durability of rights in the entire system. Mervyn King and George Soros have also made a similar point recently, suggesting that the ‘utility’ functions of an investment bank–transaction execution for third parties, managing of current accounts and money markets, etc.–should be separated from proprietary risk taking. Worth considering, I think.

I wish I read as many headlines about that in the New York Times as I do about bank executive compensation.

I think I explained it pretty well in this post

http://brontecapital.blogspot.com/2008/10/1934-securities-exchange-act-and-all.html

And I think the explanation is right.

John

“if the Fed had only bailed out Lehman as they had Bear Stearns and AIG before.”

Only Bear was before; AIG was after.

I think it is interesting, for comparison, to note the size of the 1997 crisis in this graph. Before last year it probably would have looked pretty big.

The Lehman failure revealed to the rest of the world a new reality which had been hidden before the event. The new reality was that large private financial institutions in the U.S. did not have enough financial resources to meet all the obligations they had undertaken. When Goldman and others insisted to AIG pay off on their bad bets and AIG could not do so, investors all over the world now knew that private banking had failed in the U.S.

What happened after Lehman failed was due to the fact that debts could not be paid by large private institutions in the U.S.

We cannot wish away the reality by pretending that the U.S. government could have somehow hidden the reality from the rest of the world.

Certainly Lehman was a hugely important event. It was undertood as a signal that the government would not generally bail out every major US financial institution, but would instead selectively choose which ones to bail out and which ones to let fail, without any understandable selection criteria. Since all major US financial institutions were insolvent, the result was immediate and severe panic, to which the government reacted by changing its mind and generally bailing out every major US financial institution. It then took a while for markets to understand and trust the new policy.

The fact that Lehman’s bankruptcy is still dragging on demonstrates pretty clearly that sending most of the US financial system through ordinary bankruptcy would have been a nightmare. On the other hand the quick bankruptcies of GM and Chrysler demonstrate that the US government does have enough muscle to push through restructurings of very major companies that wipe out equity, swap out debt at deep discounts, and keep the companies mostly operating through the process. That is what I think should have been done with the banks and AIG.

It was a crisis that demanded leadership. George didn’t see it coming, then went into denial when it became obvious, then dithered, and then finally decided you can solve problems by throwing money at them after all.

Ivars: It is a system. It does resonate, at times. It is not linear, so forget your electrical engineering equations. It has damped oscillations at times, and un-damped, expanding oscillations at other times. But you are on to something by thinking of it as an interacting system of stocks and flows.

I have been reading some of Milton Friedman’s writings for layman. He maintains that free markets are the solution to every problem. Economic problems arise only because markets are not free.

I wonder what he would have said about the falures of Lehman Brothers and AIG?

Mike: Thanks, thats encouraging. Non-linear oscillating systems – of course.

I just wanted to say that reaction to Lehman panic delta pulse is mostly linear, for some reason, as if nonlinearities are damped, bound together by viscous forces of trend following. Its get so viscous that it becomes elastic. So this elasticity is the reason of system loosing its usual turbulent character.

Time constants revealed via this deep pulse could be sitting very deep in the system. Its a time constant that tells how fast system gets viscous and elastic from turbulent, and how fast it relaxes back. During elasticity regime, stock market is easily predictable.

As panic wades, viscosity gets reduced, system gets more degrees of freedom, becomes viscous liquid from elastic material, non-linearity returns, turbulence restarts.

The interesting stuff is then to note when system enters elastic regime and when it hits the bottom in it since it will come back every time. A sharp drop in price is the first sign of approaching elastic , linear regime.

Something like that.

Jim is being polite. The fact is that on July 15, 2008, oil burst big time and went straight down in a vertical plunge, unaffected by the Fed, Lehman, the election or anything else, straight down.

Our energy based economy deflated to get better control over constrained oil supplies. We know who did it, the suburban, automobile based consumer.

Taking the sequence in its proper order, it’s fairly easy to see that One of These Things is Not Like the Others:

Bear, acquired by Jamie Dimon and JPMChase in March. It’s custodial business being put into bankruptcy proceedings would have frozen a large portion of the U.S. financial markets for the next four weeks (at least). Contagion effect galore, major systemic risk. Had to be saved in some form.

Lehman – Had six months to decrease its exposure and/or merge, in a steadily declining environment. Did jack. Exposure mostly limited, no contagion effect beyond counterparty risk that other firms had had six months to manage/neutralize.

AIG – Should have been bankrupted, perhaps, but contagion effect again–most especially with major European banks as well as most major U.S. banks who counted on netting and put on contracts that were ridiculous (in magnitude, not concept). Needed to be kept functional, even if we agree that the subsequent firm management has been a cf than Warren Buffett, Jamie Dimon, and others were too smart to allow.

Lehman fails on Monday. AIG is saved on Tuesday. The second act allowed the survivors to play Chicken with impunity, knowing that a wholly-owned-and-operated Treasury Department and Federal Reserve were willing accomplices.

Cochrane and Zingales contend it was Bernanke & Paulson’s overblown response to Lehman, rather than Lehman.

If you look at their data, however, the “response” of Libor does not align with the announcement of TARP details… It aligns almost perfectly, however, with the failure of Washington Mutual…

The markets took Lehman amazingly well – but until the Fed let WaMu go down, there was a notion that Treasury/Fed would take a softer line with commercial banks. WaMu tore the rug out, and the subsequent failure of the Fed to respond with anything other than “sterilized” monetary action (as Hamilton argued elsewhere) put the nail in the coffin.

I’ve argued this in comments at Scott Sumner’s blog in a bit more detail.

http://blogsandwikis.bentley.edu/themoneyillusion/?p=2810#comment-9547