How scary is it?

The Wall Street Journal reports:

A sudden drop-off in investor demand for U.S. Treasury notes is raising questions about whether interest rates will finally begin a march higher– a climb that would jack up the government’s borrowing costs and spell trouble for the fragile housing market.

This week, some investors turned up their noses at three big U.S. Treasury offerings. Demand was weak for a $44 billion 2-year note auction on Tuesday, a $42 billion sale of 5-year debt on Wednesday and a $32 billion 7-year note sale Thursday.

The poor demand, especially from foreign investors, sent the bonds’ prices sharply lower and yields higher.

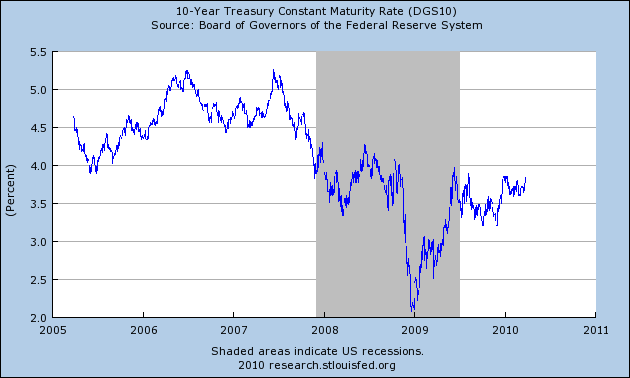

Paul Krugman (also here) and Brad DeLong are not concerned, noting we’ve seen lots of yield changes of this size or higher in the past.

|

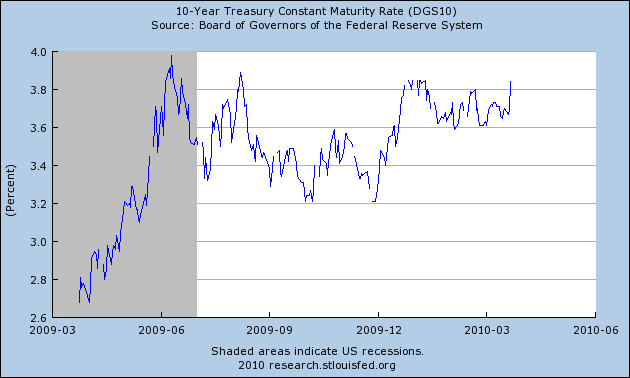

Even so, whether demand will continue to be there for burgeoning U.S. debt is obviously a question of great interest. Yields are now near the highest levels we’ve seen since the Lehman failure in September 2008, and if they continue to move up at their recent pace I wouldn’t want to dismiss it as an irrelevant development.

|

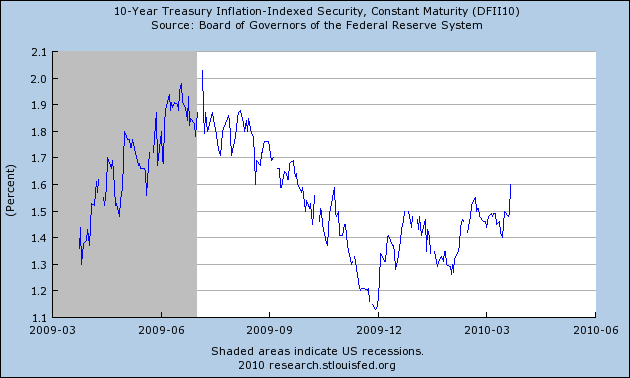

One possibility that I think we can rule out is that recent bond moves signal renewed worries about inflation. The recent surge in yields on Treasury Inflation Protected Securities is just as dramatic.

|

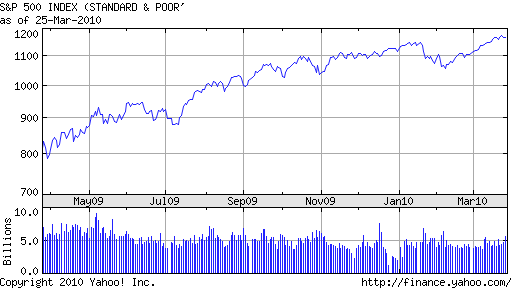

Also, if the WSJ explanation was the right one, I would have expected the increase in interest rates to depress stock prices. But stock prices have been going up along with bond yields.

|

When bond yields and stock prices rise together, I would usually read that as a signal of rising investor optimism about future real economic activity. The February numbers for home sales and other indicators that we’ve been receiving most recently don’t exactly support that thesis. Let’s hope that investors are correctly anticipating that better news lies ahead.

As Krugman pointed out the rate rise that the WSJ is making so much of is an increase in 10-year rates from 3.67% on 3/22 to 3.91% on 3/25.

As DeLong points out we’ve had many such spikes in the past. In July 2003 for example the 10-year rate rose from 3.56% at the beginning of the month to 4.49% at the end.

There weren’t a lot of stories calling that spike in rates a sign of imminent US bankruptcy back then. There were however a lot of stories about increased optimism about the economy.

One unusual result of the spike is that the spread between 10-year aaa Corporate bonds and 10-year T-Bonds went negative for the first time in history. I’m surprised the bond vigilantes haven’t made more of this fact.

However, although it may be unprecedented for the 10-year swap to be negative I still don’t think it has anything to do with default risk. Most research show that default risk plays very little role in determining aaa corporate bond spreads. On the other hand the spread does correlate very well with the slope of the Treasury yield curve. One rationale for this is that a steep yield curve is a optimistic sign for the economy.

The gap between the 10 year Treasury bond yield and the 3 month T-bill reached 3.67% in January on average. In the 682 months for which we have data (since 1953) that’s only happened in 6 months: August and September 1982, June 1984, April and May 1992 and May 2004. So it’s a “tail” event. The 10 year swap was narrow in each of those months as well. Friday the gap closed at 3.74%.

And why is the yield curve so steep right now? ZIRP. When was the last time ZIRP was effectively in place? 1941. Weird things happen in ZIRP and expect more in the months to come.

I strongly urge the deficit worrywart to put their money where their mouth is and short U.S. bonds. I know some investors that have done that for Japanese bonds 15 years ago… and lost their shirt as a result.

JDH,

The question is not, “why are rates rising?” The question is, “what is the implication of higher rates?”

Even a positive rising rate dynamic — one driven by recovery expectations — has an adverse effect on rate-sensitive parts of the economy. The stock market incorporates a view on this. That is, equity investors essentially bet that rate volatility will be low, mostly because the yield curve is anchored on the short end by ZIRP for an “extended period”. Rising stock prices tell us that a moderately strong recovery will make up for the negative effect of a slight rise in long term rates.

What equity investors will not like is a “100yr flood” in the yield curve steepness. That is, if rates rise quickly while ZIRP is still in effect — creating a 300bp+ 2/10yr spread — then the market will be “surprised” by a negative development. Rate-sensitive sectors of the economy may be so negatively affected as to jeopardize the overall recovery. This is a recipe for a steep equity market correction.

Given that the yield curve is already at record steepness, we are in uncharted territory. Call it “crowding out”, or call it something else, but a >4% 10yr does not fit with a 0% Fed Funds rate. It raises fears that deficit financing needs are keeping real yields abnormally high, and that this problem will not go away without additional QE. Another question to ask is, “how high would the Fed allow the 10yr to rise before resuming its Treasury bond purchase program?”

Krugman and others point out that nominal yields are relatively low historically. I would ask them, how high should yields be given that the short end is at zero and will remain so for an “extended period”?

The Chinese just reported a trade deficit for March, so there goes Timay’s best customer. Unless he can get Benny and the Inkjets interested again.

But esoteric finance aside, the classic interpretation of stocks up, yields up, is a bull economy and stock market.

That is a little hard to believe from an economic standpoint, and also volume is low on Wall Street, and it is the High Frequency Trading Super Computers that are selling stock to each other.

I’ve got my own theory. I think that yields have to rise to a point where people think they have somewhat normalized, then they will be more willing to make a 2,5,10, or 30 year bet on Treasuries.

If you buy now you can be trapped with a paper capital loss for a long time, and if inflation does pick up you either have to sell and take the capital loss, or hold to maturity and get your inflated away face value back.

But good news for economists, this is called “raising inflationary expectations”, a good thing.

Once rates are high enough, I think the Treasury market will eat the stock market, because the stock market is overvalued, certainly based on 2% forecasted GDP growth combined with the Great Bull Market PEs it sells for now.

So this way we can fund federal deficits without a lot of foreign investment. But there is a caveat, we need $9 trillion in new treasury sales over the coming decade (the thing that Krugman and DeLong are only mildly concerned about) and that would mean the stock market would be closer to DOW 3600 instead of DOW 36000. (And there goes the university endowment fund!)

Unless Benny and the Inkjets get interested in buying stocks. Could happen I guess. GLD 36000 too, most likely.

The other caveat is that maybe no one buys and holds bonds anymore, the market is all traders, and we don’t know what they are thinking while trading 30 year bonds.

Unless Benny and the Inkjets …..

Odd that you don’t mention the influence of Treasury’s ongoing deposits into the supplementary financing account, since you’re one of the few who mentioned it when it was announced.

Since late February, Treasury has been selling an additional ~$25 billion a week of Treasuries above its actual financing needs, and depositing the proceeds in the supplementary financing account. That simultaneously increases the supply of Treasuries and decreases the volume of dollars in private hands.

This monetary de-stimulus is scheduled to run for another roughly four weeks, coinciding/overlapping with the Fed’s winding down of the monetary stimulus of MBS purchases. It appears that the build-up of reserves hit its peak between two and four weeks ago, and the Fed is now testing some mild tightening.

There is another way to explain why Treasury markets sold off while stock market bulls took it in stride and kept on rallying: The former are closer to the fire.

Probably some optitmism, but mostly it seems like investors see treasuries as a less safe place to park their money. If only they could feel the same way about commodities.

Investors may be raising cash to invest in the supposed spike in GSE MBS rates when the Fed stops their purchase program. Plus there is the usual end of quarter dressing the balance sheet with cash.

“Even so, whether demand will continue to be there for burgeoning U.S. debt is obviously a question of great interest.”

As opposed to what, holding non-interest-bearing cash? For the private/foreign sector in aggregate, those really are the only two options. Any individual can decide to invest in stocks, corporate bonds, whatever, but whoever he buys that asset from now has a pile of USD and the same choice of cash vs. bonds. The money has already been created, when the deficit spending occurred. If its holder prefers the liquidity of cash instead of the income of a bond, that’s fine by me. Or maybe, or Mark suggests, people are preferring short-term assets (of which cash is the ultimate) because they expect short-term rates to be higher in the future than now. That’s a policy variable controlled by the Fed, so expectations of a rise are a reflection of optimism about the recovery. There is no “financing crisis”.

Stocks and nominal interest rates rising together could also indicate rising inflation expectations.

A Picture of well monitored and effiscient economies

There are many paradoxes in the financial markets,but the one of savour ” The more one borrows the more expensive it becomes” please see P50 the Debt ratio of non financial corporations and P51 the net interest rate burden of non financial corporations in Europe.

ttp://www.ecb.int/pub/pdf/mobu/mb201003en.pdf

Not to worry as Inflation expectations by professionals is very low P58. It is interesting to compare the barometer of inflation perception throughout the age with the inflation as recorded by SGS.

http://www.shadowstats.com/

“The credit-rating firm’s annual report on risks faced by weaker companies and their investors found that 995 of the 1,300 companies Moody’s rates as “junk” have debts maturing in the next five years. The debts are largely tied to the last decade’s leveraged-buyout boom.

Moody’s said these companies could face trouble refinancing their balance sheets and avoiding default should the economy and lending markets remain weak. The biggest maturities come between 2012 and 2014, when about $700 billion in bank and bond debt comes due, Moody’s found. Maturities over the next two years are much smaller, at about $100 billion”

Everything is for the best in the best possible world,the most accurate perception will always be the tax collection if savers are still alive,and the most worthy club, the club de Paris (the club debenture is still low,no doubt it will increase) if tax payers are still alive.

The rise in stock prices thus far seems to have been warranted given the improvement in after tax corporate profits that has occurred over the past three quarters. Additionally, I think it is very difficult to argue that macroeconomic indicators have not improved since this time last year.

Many also make the mistake of simply examining the magnitude of the increase in stock prices and declaring it to be unwarranted given the rate of improvement of macroeconomic indicators. What these commentators seem to always neglect is that the S&P 500 in the mid 600s was horrifically undervalued by nearly every measure and that the implied expected future economic conditions were far far worse than what we have seen. The simple truth is that the stock market should never have declined anywhere near as much as it did.

Mr. Hamilton,

Um, I can’t speak for you, of course, but I’m seeing generally deflationary pressures in the economy (total aggregate credit in the Z1 is declining) and we’re also on the verge of institutional and sovereign defaults, which would add more to deflationary pressures–and we still have yet for the over expansion of credit to implode in the Canadian, Australian, Chinese, and even parts of the UK economy. On top of this the money multiplier is bottom bouncing.

Someone like Mr. Krugman’s opinion you can usually throw out as it is typically politically motivated to cover up a previous bad assessment on his part–he has done good work in some of his academic work, but for whatever reason it almost always fails to translate into his editorial rabble rousing (as we’re seeing with his recent support of health care and all the great benefits it would bring us–and now we see very puzzled congressmen like Mr. Waxman issuing letters to AT&T and other companies demanding that they immediately begin saving money on the reform in accordance with Congressional assessments).

Rising interest rates in the face of deflationary pressures? That doesn’t sound like a rosy picture to me.

And there’s investors in the stock market? The only people I see, Mr. Hamilton, are traders playing the volatility and the March bounce–people are actually withdrawing their money from the stock market.

In 2009 there was a “flight to quality” that depressed treasury yields. In 2010 there is a “flight to equity” as people fed up with non-existent yields jump on the stock bandwagon. This may be irrational and dangerous investment behavior, but it certainly has nothing to do with inflation fears.

Some evidence coming out that gold and silver are really paper too, so those commodity ETFs may not be such a good idea either.

Probably better to buy your cornflakes at the supermarket. If you find out the cardboard box is empty, you probably can get your money back.

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/former-goldman-commodities-research-analyst-confirms-lmba-otc-gold-market-paper-gold-ponzi

I would hope that by now political partisans would stop looking at short term stock market movements to justify one-way-or-another their political views.

But the Treasury market is a much scarier place. Remember that the primary dealers *HAVE* to bid. They bid back 5 bps thinking that would get them out of the auction. That’s the only reason this sorry deal didn’t tail by 15bps.

Historically, inflation expectations largely determined the premiums in money market yields. Now its “crowding out”. But by what calculation can we measure the increased demand for loan-funds associated with our bloated bureaucracies?

It’s my discovery. Contrary to economic theory, & Nobel laureate Dr. Milton Friedman, monetary lags are not “long & variable”. The lags for monetary flows (MVt), i.e., the proxies for (1) real-growth, and for (2) inflation indices, are historically, always, fixed in length. However the lag for nominal gdp (the FED’s target??), varies widely.

Assuming no quick countervailing stimulus:

2010

jan….. 0.54…. 0.25 top

feb….. 0.50…. 0.10

mar…. 0.54…. 0.08

apr….. 0.46…. 0.09 top

may…. 0.41…. 0.01 stocks fall

Should see shortly. Stock market makes a double top in Jan & Apr. Then the real-output of final goods & services falls/inverts from (9) to (1) from Apr to May.

Recent history indicates that this will be a marked, short, one month drop, in rate-of-change for real-output (-8). So stocks follow the economy down (presumably with yields moving sympathetically)

The rate-of-change in inflation should top in Mar. (e.g., CRB index). Later on this year, the inflation rate drops sharply/inverts after Sept month-end.

Mark says: “There weren’t a lot of stories calling that spike in rates a sign of imminent US bankruptcy back then.”

By “back then” do you mean 2003?

I am not sure of the number of stories calling for a plague of frogs but wasn’t it Mr. Krugman who in 2003 said that he’d be switching to a fixed-rate mortgage because of mounting deficits and the inevitable insolvency of government?

Whereas it is true that we have had rather rapid rates of change of interest rates in the past, what has not been of concern in the past was the impact of these changes upon the valuation of interest rate swaps. This should be of concern now. (Yes, I have a propensity for understatement.)

But, truly, why be concerned? Certainly institutions are now more than sufficiently capitalized to compensate for the (potential) resulting changes in swap cash flow requirements and associated basis risk. Surely.

Optimism is increasing. I suspect that President Obama inspired confidence by passing the health care package. Paradoxical as that sounds. His obvious snub of the Israeli prime minister also helped.

The fed should confirm the recovery by raising rates a modest 25 basis points. Sooner than later.

My take:

Increasing debt over the last 20 years is shortening the leverage cycle, but the tools we use to go through these cycles is an order of magnitude more accurate. We are an older nation, also, we have all seen this before.

So we do this minor double dip, almost on schedule, as if planned. A quick inflationary spurt lasting a few months followed by the exit strategy for Congress and the Fed.

As if the “Hidden Hand” is saying, OK, I have figured this out, so now I go through my scheduled double dip and then get back on track.

“I strongly urge the deficit worrywart to put their money where their mouth is and short U.S. bonds.”

I don’t gamble with the bond money. I think that Treasuries are very high, and I expect them to move lower. I am looking for 5.5 — 6% over the next couple of years. But, I am patient. The markets can be irrational longer than I can stay liquid.

The question is not, “why are rates rising?” The question is, “what is the implication of higher rates?” – David Pearson

Um, not a very health rhetorical device, that. Rather like saying some intellectual puzzles are better than others. “Why” is an entirely legitimate question, right along with “what”. The fact that one questions suits David better than another doesn’t mean Hamilton’s question is not “the” question. It is Hamilton’s blog, after all.

Tom,

True enough. Treasury has, at the behest of the Fed, returned to its “normal” schedule of 56-day bill auctions. The drop to a $5 bln auction size from $25 bln was done to accommodate the debt ceiling, so the Fed essentially eased a bit up to late February, then re-tightened when the debt ceiling was increased. Problem is that the big rise in ten-year rates took place took place about a month after the return of $25 bln 56-day auctions. It’s not obvious why we should have a sudden rise rather than a progressive one, a month after the onset of the drain, if the drain is the culprit. Doesn’t mean the re-tightening is not a factor – it makes sense – but just that the evidence is spotty.

Badger,

If we saw consistency across inflation-expectation indicators, inflation expectations would make a good story, but we don’t see that.

Joseph,

Tsk tsk. How dare you say that people are fleeing to equity? The all-knowing and all-seeing “Brian” has informed us that he sees “people” withdrawing their money from the stock market, with the only reason that it appears to be going up (or at least not definitely down) due to presumably non-human “traders playing the volatility and the March bounce.” Get with the program, tsk tsk.

What puzzles me is not the movement in interest rates, but the spreads.

As noted above, yields on commercial AAA 1-yr are below 10 yr treasuries. I’m also hearing that yields on t-bills are above LIBOR and above the yield on Berkshire-Hathaway notes. While I have not checked this against primary data sources, I understand that all of these are highly unusual events.

Is that what everyone else is seeing?

I just came across this perspective on the interest rate spike. Steve Randy Waldman also looks at yield curve slope but uses different terms to compute the gaps:

http://www.interfluidity.com/v2/603.html

I crunched the numbers and it turns out the gap between 10 year and 2 year T-Notes reached an average of 2.83% in February which is a record on data going back to June 1976.

@Simon van Norden,

Thanks for the heads up on the LIBOR and Berkshire-Hathaway notes spread. I am going to investigate. I’d thought I’d seen everything when t-bills went negative in December 2008. Fascinating!

OK, Treasury yields are up, yield curve is steeper, and swap and AAA bond spreads are negative. Its tempting to draw broad conclusions about “what it means” but I tend to look at it fairly mechanically.

More supply of long term Treasuries: As all investors are aware, the supply of Treasuries has been increasing, and Treasury is looking to move out on the curve to protect the Federal governments income statement against future rate increases.

Less demand for long term Treasuries: As the US economy recovers, investors are looking to diversify their portfolios and reduce rate sensitivity. Where can they go? For mid-tier and high-yield corporate credit, spread compression has run its course, so you take profits and sit in cash. Munis? Credit risk is a worry. Other sovereign debt? High deficits. Equities? Well, maybe…

The MBS trade: One way to cautiously diversify is to start buying higher-quality MBS. The Fed is ending its $1.25T purchasing program (20% of the market), but says it will start again if needed. For a 114 bp yield pickup, you can own paper with some liquidity backstop.

So you focus on staying liquid and not losing any money while you consider your next move. This means lighten up on Treasuries, especially on the long end, hold cash, shift into scarce top-grade corporates, and buy MBS (also near record low spreads).. Is it any surprise that credit spreads are low (negative) and the curve is steep?

One other comment on swap spreads. To the extent they reflect counterparty risk, it makes sense they are at historic lows. Since Lehman, the industry has put a lot of focus on minimizing this risk — liquidity, cash collateralization, faster and more efficient settlement, clearing initiatives, etc.

If the Treasury market was anticipating higher inflation, today’s news on iron ore and steel prices certainly justifies that. Keep in mind there are many kinds of inflation and the official calculation of CPI is a peculiar mix of select ingredients, including a big portion of fictional “owner equivalent rent”, that has been strongly negative and thus balancing out gradually accelerating positives in most of the other ingredients. The TIPS market only measures expectations of officially estimated CPI.

kharris: One would expect such big increases in the volumes of weekly Treasury sales to have a quick effect on prices, and the evidence is plenty clear that they did. As for the decrease in money supply through the SFA deposits draining reserves, that so far has been quite minor relative to total money supply and would not be expected to have much effect.

Tom says: “The Fed is ending its $1.25T purchasing program (20% of the market), but says it will start again if needed. For a 114 bp yield pickup, you can own paper with some liquidity backstop.”

30 yr agencies are 4.48%. 10 year treasuries are around 3.8%. 30 year bonds are 4.76%. Yes, the agencies have duration characteristics similar to a 7-10 yr bond, that is until you have a significant interest rate move up. Then suddenly it has more in common with a 20 year bond.

Historically, the agency MBS are about 25-50bp above 20-30yr treasuries I believe. I don’t know what sort of “114bp pickup” you are talking about. I see instead a 30 year MBS that needs to go to 5-5.25%. (75 bp higher than here).

Mike, I was using Bloomberg data on MBS spreads. Not sure if they incorporate extension risk (probably not, I think it was just vs 10Y Treasury) or what vintage the pools are using, so I wouldn’t suggest anyone trade on the data. Interestingly, the spreads Bloomberg calculates are near their lowest point, but I would guess, with all the underwater mortgages out there, average duration will be greater than originally modelled even without higher rates… which merely reinforces your point that the yield is too low. My main point is that investors are looking for safe diversification out of treasuries, driving spreads down on scarce alternatives like hi-grade corporates and quality mbs. All that fixed income money that went into supposedly AAA MBS before the meltdown fled into Treasuries, and is still looking for a new home. No wonder spreads are all over the map.

Spreads are another concept that went the way of the dinosaur.

Riddle me this. Yahoo quotes the 30 fixed mortgage at 5.11%. The data on GSE MBS default rates is now up to 5.5% (from less tha 1% historically), and this doesn’t include the “shadow inventory” that banks haven’t recognized yet, due to current “extend and pretend” policies.

Does this imply a complete failure of the public school system in teaching us math?

Not completely, methinks, but it must mean we have total confidence in Mulligan(do over) Banking and Investment. So GSE explicit guarantees factor in greatly.

A funny corollary is Barney Franks’ statement on MBS is not guaranteed (at least older ones) made the market figure out he’s wrong about that(confirmed afterwards by Treasury itself), and an even funnier result is that the stock of mortgage insurers have been on a tear recently. So no downside there either, because Uncle SIV has your back.

Charts and data here.

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/january-fannie-mae-delinquency-rate-climbs-new-record-552-14-bps-higher-january-double-year-

Barkely – Re your comment to brian – I really wonder what is going on in the equities market. Who would be buying shares in across-the-board indexes? For the past year or so, you could get the appreciation on equities without forgoing the interest on your capital by going long in the futures market. Better than that, actually. The spot price is about 50-60 points above the 90-day futures price, so you get an automatic 2% or so annual gain on roll-overs, plus you can still get interst on your capital. The cost of the contract and the margin requirements are negligible, so why buy equities directly?

For example, if you invest $100,000 directly in equities for one year, you get the appreciation plus dividends on the equities. If instead you buy a DOW futures contract (with margin of a few thousand and transaction cost less than $40), you get the appreciation on over $100,000 of equities, plus 2% on roll-overs, plus 2% or so in interest on the money you would have sunk in the equities. Since dividends are nowhere near 4% for the broad market, it seems the only broad index equity purchasers would be those who can’t access the futures market.

If you don’t like brian’s story, do you have a better one?

The Chinese run a trade deficit with their regional trading partners. So a good strategy for them would seem to be thus: Use surplus of dollar assets to pay down Chinese trade imbalances. Also invest heavily in global oil production knowing that a surplus of dollars will cause dollars to migrate to the oil producing nations. This dollar migration though could be made less noticeable if channeled through the largest possible number of nations, thereby hiding to some extent the fact that the supply of dollars is rising at an increased rate. The Chinese could then, during this window of time, stock-pile oil and they might also encourage their trading allies, especially those in the new ASEAN-China trade arrangement, to also store as much oil as possible. This would create the illusion that the demand for oil is rising. As the cost of oil rises that could provide a hedge against the ultimate fall of the dollar if the Chinese are able to divest enough dollars into oil and other commodity investments.

The Chinese Government announced as part of its 11th 5 year plan, back in 2006, that it wanted to diversify its portfolio away from dollar related assets. The Chinese also formally announced that they believe that they are being made the victims of the Triffin Dilemma (2008).

The USA on the other hand, caused a global meltdown, and that allows the Chinese the political capital to act in accordance with whatever they deem to be in their best interest. A cheaper dollar could of course improve US exports and thereby the job situation, but in conjunction with higher energy costs, and higher interest rates due to falling demand for the dollar, the Chinese might in the end might say: “be careful what you wish for” (or some equivalent).

More on mortgage insurers. Looks like you can buy insurance (spread down), but not get paid on insurance (spread up). State insurance regulators are trying to help, moving capital requirements down (spread down), but payment picture on insurance payment gets worse (spread up). These MIs also insure muni bonds, so I guess we shouldn’t be surprised that the state regulators get confused about what their job is again.

But this is another tidbit that needs to go to whoever it is that figures out what spreads should be. Along with phoney CDS.

http://www.zerohedge.com/article/gse-delinquencies-hit-all-time-highs-what-about-monolines

Dr. Hamilton and others,

In regards to Mr. Pearson’s comment about the Fed engaging in a ZIRP and the difference of said policy’s impact on yields now vs. in the past, could we also apply the the Taylor rule, allowing us to speculate a rate below zero, and see that the steep rise may even be steeper?

In other words, if the Taylor rule gives us an idea of the Fed rate needed, and a way to move lower than the zero bound is through fiscal stimulus, could the yields be seen as more dramatic when combining current fiscal policy in addition to monetary policy? Could investors be pricing both into the yield?

I have not heard anyone looking at it this way, so I could be way off, but was curious to hear anyone’s thoughts.

Finn,

…could we also apply the the Taylor rule

People should only talk about the Taylor Rule when unemployment is at exactly 6%, because that is how John Taylor intended his rule to be used.

…allowing us to speculate a rate below zero,

No, because the Taylor Rule is empirically derived, and that would be like saying water freezes at 32F, and freezes even more at 0F.

…and see that the steep rise may even be steeper?

That is something that some economists would do, but any investors that still have their net worth, and would like to keep it that way, would not.

Bond traders get confused enough with bull flatteners, bear flatteners, convexity and butterflies. If you give them the Taylor Rule to consider, I’m afraid their brains would explode.

Cedric,

Thanks for the help and analogies. In reading Taylor’s paper I didn’t see the reference to unemployment at 6%; do you have a source where it is stated (for future ‘discussions’ with friends)?

Finn,

I’ll disclose that the “exactly 6%” was my idea, sort of an alarm that goes off when crossed from either direction. But after seeing the Taylor Rule intellectually raped across the blogosphere, I decided John Taylor needed the help.