The Keystone Gulf Coast Expansion Project is now entering its fourth year of regulatory review, and is currently on indefinite political hold. In the mean time, the market is figuring out other alternatives.

A key demonstration of the need for better oil transportation infrastructure in the United States is the price gap between West Texas Intermediate, a light, sweet crude traded in Cushing, Oklahoma, and Brent, a similar crude from the North Sea. The Law of One Price suggests that these very similar products should sell for a very similar price, and indeed for most of their history, they did exactly that.

|

However, a remarkable spread between Brent and WTI began to develop at the start of last year. New production of crude from North Dakota and Canada, decreased U.S. demand, and pressure on European supplies of light, sweet crude from developments in Libya all changed the relative supply and demand situations in the central U.S. and Europe. Brent began to break away completely from WTI, with the spread last week bumping back up near $20/barrel. The spread between Brent and North Dakota crude is even more dramatic, with the latter selling at up to a $40 discount to Brent.

That price differential is a very loud market signal that we’re using available resources extremely inefficiently, and impoverishing ourselves in the process of paying so much to import oil from places like Nigeria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela. That market signal is also a strong incentive to anybody to try to figure out a way to transport the lower-cost crude now available in the northern and central United States to refiners on the U.S. coasts, who are currently paying inflated prices to obtain oil from overseas.

One logical solution would be TransCanada corporation’s Keystone Gulf Coast Expansion proposal

to build a major new pipeline to carry oil all the way from Canada and North Dakota down to refiners on the Gulf of Mexico. As obvious and logical as this is from an economic perspective, it unfortunately became a political symbol for some broader controversies, whose net effect has been to paralyze the Obama Administration from moving forward.

|

But there is more than one way to skin a cat. Enbridge, another Canadian company, has purchased half-interest in the Seaway Pipeline, which historically had been used to carry oil from the Gulf of Mexico to refiners in Oklahoma. Enbridge’s plan is to invest in the infrastructure necessary to allow oil to move in the opposite direction through that pipe in order now to bring crude oil from Cushing down to refiners on the Gulf. Enbridge announced on Friday that this process is well under way:

The initial 150,000 barrels per day (bpd) of capacity on the reversed system could be available by the second quarter 2012. Following pump station additions and modifications, which are expected to be completed by the first quarter 2013, capacity would increase to 400,000 bpd assuming a mix of light and heavy grades of crude oil.

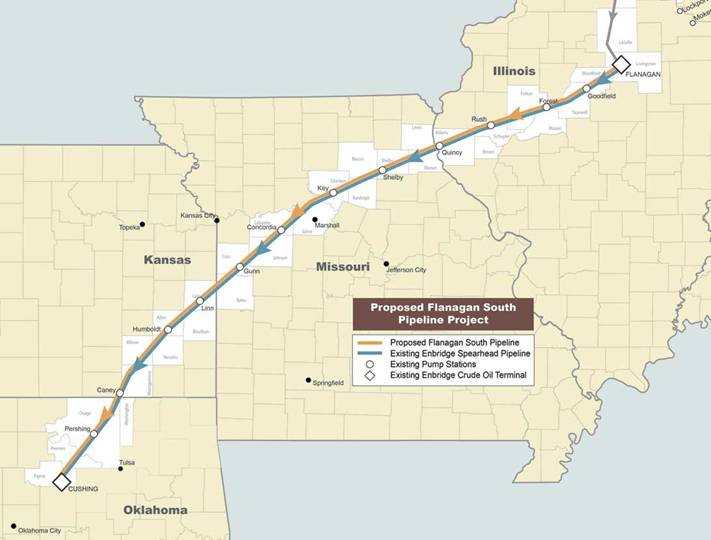

A separate plan is Enbridge’s Flanagan South Pipeline Project, which would lay a second set of pipes twinning its existing system to carry oil from Illinois to Cushing. It would serve a similar function as part of Keystone, adding capacity to get more oil from the north down to Cushing, albeit at greater cost and less efficiently than Keystone. But it’s much harder to frighten the public with images of a pipeline that goes right next to one that’s already there, and the regulatory obstacles are much more modest. Again from Enbridge’s Friday statements:

Enbridge announced that it secured sufficient capacity commitments from shippers to proceed with its Gulf Coast Access initiative offering crude oil transportation from its terminal at Flanagan, Illinois to the United States Gulf Coast. Enbridge also announced that, in response to shipper requests, it would hold a second open season early in the year to provide an opportunity for shippers to subscribe for additional capacity. The Gulf Coast Access initiative will involve construction of an additional line from Flanagan south to Cushing, Oklahoma following Enbridge’s existing Spearhead Pipeline right-of-way. This line is expected to be in service by mid 2014 at an estimated capital cost of approximately US$1.9 billion depending on the final scope of the project. From Cushing, crude oil will move to Houston and Port Arthur, Texas on the Seaway Pipeline system, a joint venture between Enbridge and Enterprise.

|

In yet a third development, TransCanada is recognizing that even if it can’t get the full Keystone Gulf Coast Expansion approved, a great deal could still be accomplished with just the segment from Cushing down to the Gulf. TransCanada is reported to be pursuing the possibility of proceeding just with that segment alone even as the broader project still waits for approval ([1], [2]).

As we develop reasonable alternatives to get lower cost oil to refiners on the U.S. coast, the price differential between WTI and Brent has to narrow. The conventional wisdom has been that this would mostly be accomplished by the U.S. price coming up rather than the world price coming down, primarily because the world is a bigger market than just the U.S. But it’s interesting that if you look at futures prices for WTI and Brent, these do indeed show the gap narrowing to $4/barrel by 2015, but that narrowing comes entirely from Brent falling down below even the present WTI.

|

It seems to me there is something “funny” about these markets that isn’t readily explained. Why aren’t these large price differences more easily arbitraged away? A truck driver could make $6000 for a day’s drive hauling oil. A railroad tank car could earn $20,000. It must be more complicated than just the lack of a pipeline.

As you noted, any oil from the US Mid-continent and Canada that reaches the US Gulf Coast will be sold at the world price, which is currently around $120. Note that Tapis crude is selling for about $130.

Many analysts point toward slowly rising US crude oil production (up from 5.4 mbpd in 2004 to about 5.65 mbpd in 2011) and a slow increase in global total liquids production (inclusive of low net energy biofuels) as evidence that we don’t have any supply problems. But they are asking consumers, in effect, not to believe their lying eyes in regard to a doubling of annual global crude oil prices in six years, from $55 in 2005 to $111 in 2011–which is fundamentally a result of the ongoing decline in Global Net Exports of oil (GNE), with the Chindia region consuming an increasing share of a declining volume of GNE*.

At the Chindia region’s 2005 to 2010 rate of increase in their combined net oil imports, as a percentage of GNE, the Chindia region alone would consume 100% of GNE in about 19 years.

The dominant trend we have seen since 2005 is that the US, and other oil importing OECD countries, are being forced to consume a declining share of a declining volume of GNE. The bottom line is that the volumetric decline in ANE (Available Net Exports, or GNE less Chindia’s net imports) was about one mbpd (million barrels per day) per year from 2005 to 2010, from 40 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2010. I estimate that this volumetric decline rate will accelerate to between 1.4 and 2.0 mbpd per year between 2010 and 2020, with ANE being between 15 and 21 mbpd in 2020, versus 40 mbpd in 2005.

The fact that the US recently became a net exporter of refined petroleum products is simply evidence that the US is being forced to reduce our oil consumption, via price rationing.

Incidentally, the seven major net oil exporters in the Americas and the Caribbean are: Venezuela, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador, Trinidad & Tobago. Their combined net oil exports fell from 6.0 mbpd in 2005 to 4.8 mbpd in 2010 (BP)–a one-fifth decline in only five years.

Slowly increasing net oil exports from Canada could not come close to even offsetting the ongoing regional net export decline.

*Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, Primarily BP data base, total petroleum liquids, minor EIA data input

Incidentally, if you look at the five year WTI crack spread, in recent years it has averaged around $10, but last year it approached $30, as the Brent/WTI spread widened. It recently fell into the teens, but has since climbed back to the $25 to $30 range. Here is a link to the graph (click on five year range):

http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/CRK321M1:IND/chart/

Gasoline prices are probably somewhat cheaper in the Mid-continent than on the coasts, but you also have to account for differences in state taxes and EPA requirements.

However, what the crack spread shows is the only real winners from the WTI/Brent crude oil price spread are the Mid-continent refiners, as they pay WTI based prices for crude oil, but charge Brent based prices for refined products.

In effect, Mid-continent refiners are offering a multi-billion dollar incentive to Canadian producers to take their oil elsewhere.

Note the extraordinary amount of backwardation in Brent, $20 to the end of the strip. What would cause oil prices to drop like that? Do traders think China will stop growing, or that oil production will somehow miraculously increase? We’ve added all of 300 kbpd of crude production since 2007–that’s effectively nothing. And that growth has been fueled by large oil price increases, which are just about played out. I am simply baffled by futures prices right now.

With the concentration of refineries in Louisiana, would it be better to encourage more geographically diversified refineries? Why not build refineries in North Dakota, near the new oil fields?

It should be noted that up to their capacity limits, railroads provide an alternative way of shipping oil, (indeed the original way thats how John D Rockefeller got his start, conniving with the railroads). BNSF just built a 100k bbl/day loading rack near Williston ND. While rail is more expensive than pipeline, is not clear that it raises the price $60/bbl. Of course if you look at the railroad network, there is a problem in that you have to go almost to Mn to get south, as there was not a lot of north south traffic in the old days. The alternative is the Powder River Basin route, but thats already 4 tracks wide and full of coal.

DanC, the regulatory hurdles to building a refinery in a new location are probably much bigger than those to building a new pipeline.

The dirth of ‘shovel ready’ jobs has a lot to do with our choking on regulation.

transcanada is planning a new route around the sandhills…it now indicates it cannot start the pipeline until 2015 at the earliest…

http://money.msn.com/business-news/article.aspx?feed=AP&date=20120214&id=14791477

It’s very telling that this post is narrowly focused on a $20 differential between WTI and Brent without any recognition of the larger issues facing us: climate change, pipeline leaks, peal oil, the extreme damage to the environment by extracting oil from the Alberta tar sands. We really need to take our blinders off and do a complete cost/benefit analsyis.

Jeffery Brown wrote:

In effect, Mid-continent refiners are offering a multi-billion dollar incentive to Canadian producers to take their oil elsewhere.

Jeffery, wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that the US government is offering the incentive rather than the refiners? The refiners are simply working under the constraints they have been given. Good comment, BTW.

Climate change is a good thing, leaks can be cleaned and the environment is resilient. And peal oil is an elaborate banana prank.

Longer term, the cancellation/delay in the Keystone pipeline project is certainly a very large incentive to Canadian producers to find an alternative route to coastal markets, but my principal point is that there is not much evidence–given the enormous WTI crack spreads–that anyone besides the Mid-continent refiners are currently benefitting from the WTI/Brent price spread.

But I’m sure some refinery executives are getting some very nice bonuses.

Thanks for this post. When the latest Keystone decision was announced, one of my questions was how the markets would adjust. Not being an oil & gas maven, I was hearing about this and only this alternative. Markets work around problems when there’s money to be made.

Thanks also for highlighting – finally, IMHO – that much of the issue is not the areas in the Dakotas but Cushing, OK to the Gulf.

Putting on my tinfoil hat, maybe Obama isn’t a selfish idiot. He might be doing a slow play. If US, Gulf, and South American oil production is poised to overwhelm US refinery capacity in several years, it makes sense of Canada to go west, both for them and us, and it makes sense not to make a point of it to drive a response from OPEC like affiliations.

Aaron,

One small problem with your scenario. There are seven major net oil exporters in the Americas and the Caribbean: Venezuela, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, Ecuador, Trinidad & Tobago.

Their combined net oil exports declined by 20% in only five years, from 6.0 mbpd in 2005 to 4.8 mbpd in 2010 (BP).

There are only two major net oil exporters in the entire Western Hemisphere that showed increasing net oil exports from 2005 to 2010:–Canada & Colombia–and as noted above, they could not come close to offsetting the regional net export decline.

The more likely scenario is that refineries in the US will continue to shut down, as we continue to be forced to consume a declining share of a declining volume of Global Net Exports of oil.

Ricardo, your head appears to be buried in the tar sands. Please remove it and do some objective research.

A long time Peak Oil Critic, John Hofmeister, former CEO of Shell Oil Company, continues to develop a much more nuanced outlook for global oil supplies. He was on CNBC this morning.

John Hofmeister link (2/21/12): Gas to Hit $5 By Summer?

http://video.cnbc.com/gallery/?video=3000073805

Hofmeister:

“(Oil) Demand globally is not down. That’s the issue. Demand continues to rise in Asia and whether we (the US) use less or not, doesn’t matter. Price is going up because supply can’t keep up with the demand . . .

I think OPEC is about maxed out. When people talk about spare capacity in OPEC, I don’t see it. I just don’t see it coming through and I’m not sure it’s there. And it’s not just that they’re greedy, but they’re really producing what they can produce.”

Dave L wrote:

Ricardo, your head appears to be buried in the tar sands. Please remove it and do some objective research.

Dave, Thanks for adding such brilliant insight to the discussion.

No problem Ricardo. Hopefully, you have an open mind and will heed my advice. Start with “The End of Growth” by Richard Heinberg or “The Great Disruption” by Paul Gilding

Dave,

I guess those were just rumors that Malthus was dead.

I’m not really sure of the relevance of your statement. Yes, we have shown that we can continue to feed billions of people, but market failures, climate change, neo-liberalism are why one billion are still starving. Of course, the main reason that we have been able to feed so many is that we have industrial agriculture which requires cheap fossil fuels which is therefore not sustainable in the long run.

Corruption is main cause of inadequate food distribution.

I agree Aaron…if by corruption you mean neoliberal policies which allow land to be taken away from the local populations who feed themselves off the land and then multinationals grab it and do large scale industrial agriculture for single crops for food such as soybeans or for biofuels such as sugarcane and palm oil. Studies show that we can feed the world with small scale organic farming which is also better for the environment (no pesticides and less fossil fuel inputs) and mitigates climate change since the healthier soil will sequester more carbon.