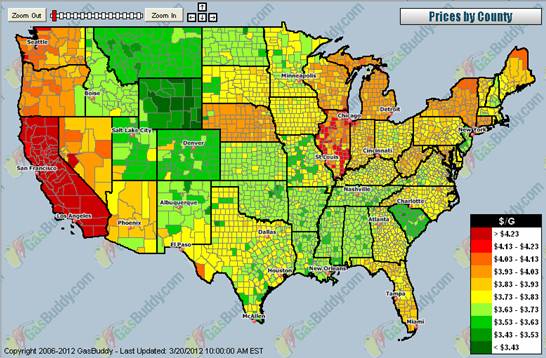

Gasoline prices differ substantially across different parts of the United States. For example, the average price in Illinois is currently 70 cents/gallon higher than that in Wyoming, and California motorists pay 86 cents/gallon more than the folks in Wyoming. Why is that?

|

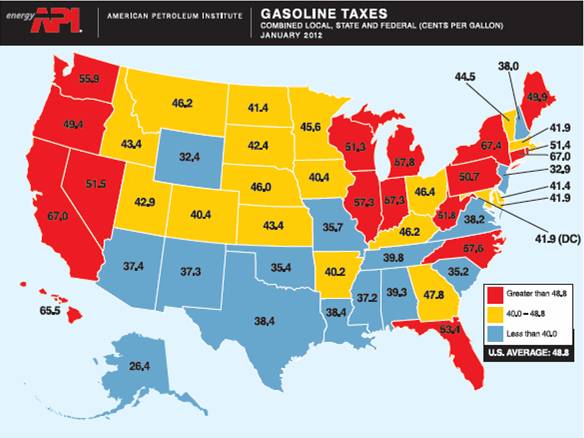

The biggest single factor is taxes. The tax on a gallon of gasoline in Illinois is 25 cents higher than in Wyoming, while the California tax is 35 cents higher.

|

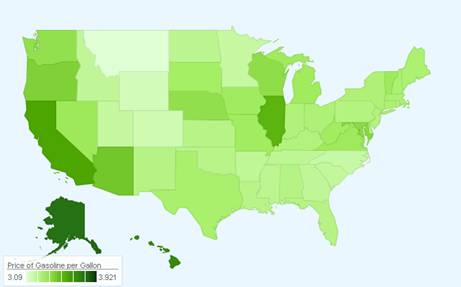

But that still leaves 45 cents of the Illinois premium and 51 cents of the California premium unexplained. Political Calculations has created a map of average gasoline prices once you subtract out taxes. (His original map, like that from GasBuddy above, also has a nice mouse-over feature if you want to see more details).

|

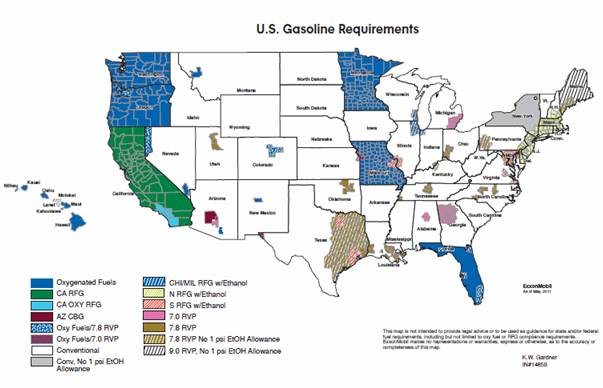

Another minor factor in the price differential is differences in the gasoline itself. Motorists in California, for example, are required to use a higher-quality fuel in order to help limit air pollution.

|

A more important factor is differences in the cost of crude oil available to refineries in different parts of the country. For example, sweet crude in Louisiana is currently fetching $125 a barrel, or $27 more than its counterpart in Wyoming. If the refined product market in Wyoming were completely separate from that in the rest of the country, we might then expect gasoline in Wyoming to be 68 cents/gallon cheaper than on the coasts as a result of differences in the cost of crude alone.

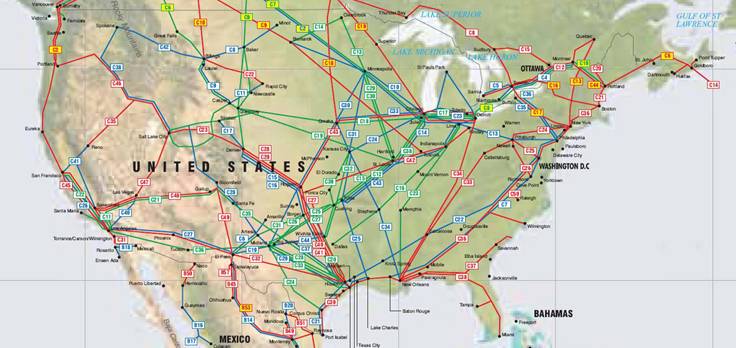

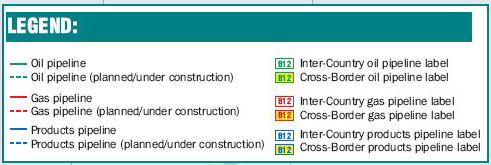

But the refined markets are not completely separated, and no producer would want to sell gasoline in Wyoming if you had an easy way to get it to somebody willing to pay 68 more cents per gallon for it. Although America’s pipeline system for transporting crude oil is not up to the task of moving all the crude available in Wyoming to refineries in Louisiana, the infrastructure for transporting refined products is somewhat better. The result is that Americans in the middle of the country pay more and those on the coasts pay less than they would if the product markets were completely isolated geographically. The equilibrium price differential is the one that equalizes the return from selling in different markets after taking into account transportation costs.

|

|

In fact, refiners in the central U.S. have such a competitive advantage through their access to cheap locally produced crude that they have turned the U.S. into a net exporter of refined products like gasoline, despite the fact that we of course are still a huge net importer of the crude petroleum itself. We use pipelines to ship gasoline and diesel to the Gulf of Mexico, and tankers from there to sell refined products around the globe. The flip side of this is that refiners on the East Coast find themselves at a huge disadvantage. Refineries accounting for half of East Coast capacity are set to close.

That means that if you live in New York and complain about paying more than drivers in the central United States, you could soon see that differential increase even more.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but doesn’t the Energy Bulletin article you linked to at the end refute its own argument? If refineries on the East Coast are shutting down because it has become unprofitable to refine and distribute gasoline in that part of the country, then wouldn’t this mean that the price of gasoline isn’t likely to rise very much after the refineries close? After all, if gasoline prices were to spike after these refineries go offline, then that will increase the profitability for any refinery operating in that part of the country. Unless the refineries shutting down plan to immediately reopen after the price of gasoline spikes on the East Coast – which would be a nonsensical business decision – it would suggest that prices probably will not rise too much even after these refineries are taken offline.

Professor, could you comment this article http://www.businessinsider.com/a-spike-in-us-oil-production-is-about-to-make-it-the-new-middle-east-2012-3

Excellent post. Very clear and informative.

Can you comment on how the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would change the geography of prices seen in the first figure?

“The U.S. has 22.3 billion barrels of proved reserves, a little less than 2% of the entire world’s proved reserves, according to the Energy Information Administration. But as the EIA explains, proved reserves “are a small subset of recoverable resources,” because they only count oil that companies are currently drilling for in existing fields.”

http://news.investors.com/article/604303/201203141303/oil-abundant-in-the-united-states.htm

Gasoline prices are inversely correlated to the freedom to extract oil from all sources… if your argument holds that nearby oil sources and nearby refining reduces gasoline prices.

Illinois sticks out like a sore thumb, even after taxes. I wonder why that is. Indiana and Illinois have the same level of taxes, but IL is still 30 cents higher. The first maps seems to indicate that prices are high throughout the state and not just in the Chicago area where the EPA requires a different blend of gasoline.

A crack spread reminder:

WTI Crack Spread ($32 Currently):

http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/CRK321M1:IND

Brent Crack Spread ($15 Currently):

http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/ACK321A:IND

The difference between WTI and Brent crack spreads, $17, is the as the difference between WTI and Brent crude oil prices this afternoon, $17.

In other words, Mid-continent refiners are paying WTI prices for crude, but charging Brent based prices for refined products.

The weekly WTI spot crude oil price in the first week of March, 2008 was $103, and the average Midwest gasoline retail price was $3.15 (EIA).

The weekly WTI spot crude oil price in the first week of March, 2012 was $108, and the average Midwest gasoline retail price was $3.82.

So, an increase of 12¢ per gallon of WTI crude, from 3/08 to 3/12, corresponded to an increase of 67¢ per gallon of gasoline.

Note that from the first week of March, 2008 to the first week of March, 2012, the price of Brent increased from $102 to $125, an increase of 55¢ per gallon of crude.

So, are product prices in the Midwest more closely tracking WTI or Brent crude oil prices?

Re: Filibuster, Here was my response:

We have seen two annual Brent crude oil price doublings since 2002, from $25 in 2002 to $55 in 2005, and then from $55 in 2005 to $111 in 2011.

In response to the first price doubling, we did of course see a substantial increase across the board in global total liquids production (inclusive of biofuels), in total petroleum liquids, in crude + condensate (C+C), and in Global Net Exports (GNE) and in Available Net Exports (ANE). GNE and ANE numbers are calculated in terms of total petroleum liquids. ANE are defined as GNE less China and India’s combined net oil imports.

In response to the second Brent crude oil price doubling (2005 to 2011), we have so far seen a very slow rate of increase in total liquids production (up 0.5%/year from 2005 to 2010), virtually flat total petroleum liquids and virtually flat C+C production (through 2010), and a 1.3%/year and 2.8%/year respective decline rate in GNE & ANE (through 2010).

GNE fell from 46 mbpd (million barrels per day) in 2005 to 43 mbpd in 2010, while ANE fell from 40 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2010. (Top 33 net oil exporters in 2005, BP + Minor EIA data, Total Petroleum Liquids.)

I estimate that there are about 157 net oil importing countries in the world. If we extrapolate the Chindia region’s rate of increase in their combined net oil imports, as a percentage of GNE, in 19 years just two of these oil importing countries–China & India–would consume 100% of GNE.

US annual crude oil production rose from the pre-hurricane level of 5.4 mbpd in 2004 to 5.65 mbpd in 2011 (through November), versus the 1970 peak rate of 9.6 mbpd.

This is helpful, but John Hofmeister, the former CEO of Shell Oil described it as a “trickle” of higher production, and we remain dependent on imports for about two out of every three barrels of crude oil that are processed in US refineries.

We do have of course have production from thermally mature shale formations, like the Bakken and Eagle Ford, but there is no commercial production from the “shale” deposits in Colorado (the Green River Formation), which is really a kerogen rich marl deposit that has to be “cooked” in order to produce a liquid that can be refined. In any case, I suspect that the net energy to be derived from these kerogen deposits is, at best, minimal.

And of course, Canada has shown increasing net oil exports, which are calculated in terms of total petroleum liquids, but the combined net oil exports from the seven major net oil exporters* in the Americas and the Caribbean fell from 6.2 mbpd in 2004 to 4.8 mbpd in 2010, a 23% decline in six years.

The dominant trend we are seeing is that the US, and most other developed oil importing OECD countries, are being gradually priced out of the global market for exported oil, as annual global (Brent) crude oil prices doubled from 2005 to 2011, and as developing countries like the Chindia region consume an increasing share of a declining volume of Global Net Exports of oil.

For more info, do a Google Search for: Peak Oil Versus Peak Exports.

*Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, Argentina, Ecuador, Trinidad & Tobago

And a metaphor:

Consider the first 15 minutes after the Titanic hit the iceberg versus the last 15 minutes before the ship sank. In the first 15 minutes, only a handful of people knew that ship would sink, but that did not mean that the ship was not sinking. In the last 15 minutes, it was readily apparent to everyone that the ship was sinking, but by then it was far too late to try to get to a lifeboat.

Let’s assume that the water was flowing into the ship at a rate 10 times faster than the rate that water was being pumped out of the ship.

Should one focus on the water being pumped out (a slow increase in US crude oil production) or on the water flowing in (the decline in the volume of net exports available to importers other than China & India)?

Gas prices are high in VA, MD, DC, and Illinois.

Socialist car hater Obama successfully raises gas prices everywhere he has lived.

Any explanation for why the parts of Indiana that require Chicago gas still have gas prices that are 20 cents cheaper than in Illinois? Sales tax?

Price elasticity is going to vary with regional incomes. Operating leverage is going to vary with the size of regional markets. Achieving target return on capital is going to require different gross margins from market-to-market. Uniform pricing is not a goal of business men, meeting minimum required return on capital is the goal. Pricing will vary across segments as segment separation allows.

Outstanding Professor. You give a lot of information to chew on. Thank you.

And tankers carrying oil from a US port to a US port must be US flagged. The Jones Act, which is from 1920.

I don’t see how regional differences wouldn’t exist in a country this size. Markets require time – and money – to shift infrastructure. Population growth in one area. Supply changes in another. These don’t flow seamlessly through the system.

I forwarded this link to my Dad and this was his reply:

“Great to see this. It would be interesting to see the breakdown of cost from the ground to the pipeline ie extraction transportation and refining PLUS speculation. Then you add on the taxes etc

–Dad”

Any thoughts on what I should tell him?

Mike,

My 2¢ worth:

Global (Brent) annual crude oil prices increased at an average rate of one percent per month (12%/year) from 2005 to 2011. Actual prices have of course been above and below this trend line, but this is the average six year rate of increase.

Furthermore, refinery profit data (crack spreads) show that US refined product prices are closely linked to global crude oil prices, and not to WTI prices. The average annual Brent price in 2011 was $111, and it is currently at about $121 this morning.

Given the fact that our study shows that the volume of Global Net Exports of oil (GNE) available to importers other than China & India (what I define as Available Net Exports, or ANE) fell by one-eighth in five years, from 40 mbpd in 2005 to 35 mbpd in 2010, I don’t think that “speculation” had a material impact on crude oil and product prices. Oil prices had to go up to balance demand against declining volumes of GNE & ANE.

I personally expect to see a continuation of this trend, subject to what happens to overall global demand.

i wonder what it would take supply-wise, in terms of pipelines and whatnot, to get the oil to the east coast – after all there is a lot of demand there.

Other factors include retail outlet cost structure. Some states have greater requirements for gas station equipment and environmental protections. Some states have higher property values, thus the real estate the gas station sits on is more costly. Some states have higher property taxes.

And some states charge flex excise taxes on gasoline. How they do that is to charge a percentage of the price of a gallon of gasoline sales instead of a flat rate per gallon.

Thus, if the price of a gallon of gasoline goes up – the tax automatically goes up too – keeping their revenue percentage constant, so there is no need to change the tax rate legislatively when the price per gallon changes multiple times over the course of a year.

If one thinks about it, this can explain a lot of why there is so much of an average regional difference over time.

@JSeydl

The price increase may not be great enough to cover the cost especially if the volume is low.

@Kevin H

Right. That’s exactly my point: Sure, prices might move up a tad, but it’s not going to be a dramatic spike. My original issue was with the Energy Bulletin article that Prof. Hamilton linked to. That is, the article gives the impression that gas prices are going to skyrocket in the East Coast and that this will be very damaging for consumers in the region of the country, when in reality there’s probably not a whole lot of upside to gas prices once these refineries go offline.