Oil prices can go down as well as up.

|

Last week Secretary of Energy Samuel Bodman warned that high gasoline prices might be here for some time, stating “we are going to have a number of years, two or three years, before suppliers are going to be in a position to meet the demands.” Other analysts have renewed their forecasts of $100/barrel oil by next winter. Given how volatile oil prices have been historically, that is certainly a possibility, though the same volatility means that a big price decrease is also conceivable. Since concerns about a further move up in price have been well represented, I thought there might be some value in trying to provide some balance by calling attention to a few of the possibilities on the downside.

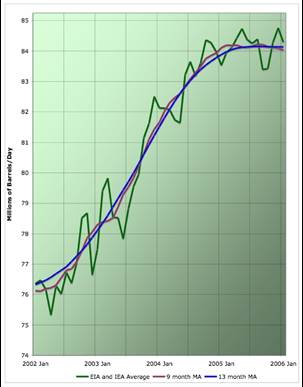

First let’s review how we got to where we are right now. Global oil production has failed to increase over the last year, in part due to what is now looking like a permanent loss of over 300,000 barrels per day from the Gulf of Mexico and shut-in production from Nigeria. Given the current limited excess production capacity, fears about the possibility of additional supply disruptions from places such as Iran and Nigeria translate into a higher current price for crude oil. As prospects for continued global economic growth appear strong, oil prices have been bid up.

So how’s any of that going to change? There remain a number of big new projects that will be coming into production over the next several years (counterargument here). And obviously if the worries about production cutbacks from Iran and elsewhere fail to be borne out, that could bring prices down. A third factor that I think deserves more attention is the effect that $70 oil and $3 gasoline will have on quantity demanded.

Gasoline demand can be difficult to predict, in part because many of the adjustments that consumers and firms make can take a long time to have their full effect. For example, the lower mix of SUVs being sold in the American market today will influence the quantity of gasoline demanded for many years to come. Given the long-run nature of such commitments, it’s hard to predict the point at which people start to make those kinds of adjustments. But at current prices, I certainly expect to see some significant moves in those directions.

|

The graph at the right displays the quantity of gasoline supplied to U.S. wholesalers. One needs to be a little careful interpreting this series as demand, since we don’t observe changes in wholesale and retail inventories, and since large week-to-week fluctuations are common. I have reduced the influence of the latter somewhat by using a 4-week moving average. These data seem to suggest that the April gasoline price increases may have been sufficient to reverse the usual tendency for the U.S. public to use more gasoline each year than the previous year. Certainly that’s what we observed last fall when gas prices were around their current values, and I see no reason not to expect to see the same thing to be repeated now.

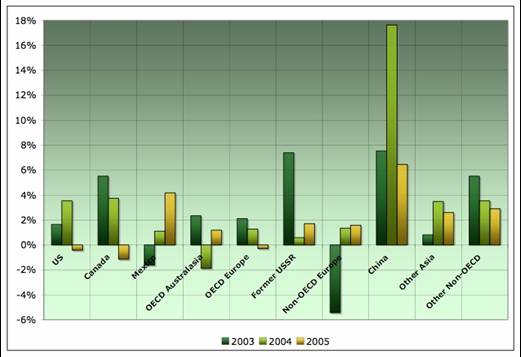

Stuart Staniford (figure below) argues that the free-market economies such as the U.S., Canada, and Europe, in which consumers have not been protected from the price increases, are the places we have seen reductions in the quantity of oil consumed so far, whereas the growth in demand is strongest where the price remains subsidized.

That is a very interesting observation, and I agree that the oil producing countries with their growing incomes may make an important contribution to global petroleum demand in the years to come. But I would hesitate to dismiss the role of the incentive to conserve even in those consuming countries where the governments currently appear inclined to pretend none of this is really happening. Even if consumers don’t have an incentive to respond, the governments themselves, however unenlightened as they may be, are surely going to notice the effect of trying to maintain a subsidy on their own budgets, and eventually will find themselves without the resources to keep their fingers in the dike.

If rats and pigeons can respond to price incentives, don’t assume we won’t see the same thing from homo sapiens.

|

Technorati Tags: gas prices,

gasoline prices,

oil,

oil prices,

oil demand

James

A few points

– opportunity cost of holding oil prices below world levels

– inelastic supply and demand for oil

– role (this time) of financial speculation

1. I think the key point is that for those countries which charge a lower than world market price for oil:

– they are incurring the opportunity cost to their economies of not selling that oil on world markets

This gets more (and more) painful as the price goes up. So far, the likes of Indonesia are prepared to pay that price (a subsidy where the cost is a lost revenue to the Treasury, rather than a cash payout, is always easier to bear).

When we had Pierre Trudeau’s ‘made in Canada oil price’ oil price during the 1970s shocks, the professor Len Waverman, then of U of Toronto, wittily pointed out, in a letter to the Prime Minister, that we should also have a ‘made in Canada Mercedes price’.

The question comes when emerging markets will crack on this, and who first. My guess is China first, as they seem to be working towards more market based incentives.

Generally, though, price elasticities of demand for oil related products are low, and with long lags.

2. Given very low supply elasticities (it takes a long time to bring on new supplies, conversely once pumping, supplies don’t stop even if prices fall) and low demand elasticities (most oil is used for transport, with few alternatives), it is unsurprising that oil spikes up in price.

One would also expect it to spike ‘down’, for the same reasons

3. a big factor in oil pricing, right now, is the amount of institutional money and hedge fund money going into managed commodity funds. That is likely to exacerbate spikes in the short run– because it is typically leveraged and arbitrage against an upward moving price series is typically difficult (that famous paper by Schlifer, that in the presence of ‘noisy’ traders, the rational arbitrageur, with a borrowing constraint, might jump on the bandwagon, not short sell against it).

I wonder what’s going on with the Gulf of Mexico production? You’d think that if it was worth drilling those wells in the first place when oil was $20, it would certainly be worth fixing the damage and putting them back into production when oil is $70! It’s hard to believe they’re just going to write off those damaged rigs and forget about the Gulf.

I agree Hal. 300,000 barrels a day is $1.5M at $50/bbl. You’d think that would be worth some investment.

I know old wells tail off, to just a few barrels a day (they call them strippers?) and that on land people let them run for years. Some of the ones over in Huntington Beach look ancient (and maybe are).

Oh well, maybe they think they’ll go back and get them at $250/bbl.

doh, bad math

Hal: I don’t have a reference at hand, but I remember reading that some of the lost capacity in the gulf was produced by wells nearing the end of their successful life. Perhaps many years of production in front of them, but still a significant way along its depletion curve. The reference indicated companies are not interested in devoting capital to reopening these wells. They would prefer–given what must be a limited resource environment (equipment and expertise, not dollars)–that they are focusing on accelerating new production already planned.

Without references, it’s speculative, but still worth considering.

You’re right, T.R. That was the claim Bodman made when he described some losses as “permanent.” My link to the news article has also gone dead, but he was definitely talking about the depletion issue.

But Hal and Odo make a good point (as always), in that maybe it would pay to redrill them at $70, or, if not here, at a higher price, so the lack of enthusiasm for redrilling may be related to the lack of enthusiasm for a lot of other projects that seem to make sense if you take the current price as permanent. So, I think I was too casual in repeating Bodman’s characterization of these losses as “permanent.” Better to say that I’m not expecting them to come back up any time soon.

I agree with comments above. Also I had forgotten the characterization “permanent” until you just mentioned it. I agree that the definition of permanent is a function of oil price. In the near term (next few years), intuition tells me that resource constraints may argue for accelerating projects under development and then revisiting these “lost” fields in perhaps five years.

Whether it’s permanent or not, it seems that they’ve stopped fixing Gulf oil rigs for the year, anyway, at this point.

We’re about to get into hurricane season again. Most forecasters agree that we are likely to see increased hurricane activity for at least the next decade, and some claim that global warming will produce ever-increasing waves of hurricane intensity. Maybe the oil companies (or their insurance carriers) see too much risk of continued hurricane damage to justify new investment in the gulf.

And as has been discussed before, oil companies persist in using $30-40 as a baseline oil price for judging the profitability of new investments. Whether this is excess timidity or cautious prudence will be more obvious in a few years, no doubt.

Back to the topic of the blog entry, there is one problem with the theory that oil prices could fall substantially. The reason offered is that demand could fall. But if demand falls, and then prices start to fall in response, demand will stop falling as soon as the prices drop back a bit.

We saw this in Q1 when SUV sales started to come back after the post-Katrina drop. In fact there were all these rather moronic headlines in April marvelling at “High SUV sales even with record gas prices”. That was dumb because the data was from Jan-Mar, and gas prices were relatively low back then, well below $3. Since then the April data has come out and already things were turning around, and I’m sure May will be even more so if gas stays high.

But the point is that in Q1, when prices moderated, demand largely returned to its historic pattern of growth. If we do start to see a softening of prices over the next few months, my guess is that demand will bounce right back. Only after years of high prices would we get enough structural change (such as a significant increase in fleet MPG) that demand might stay low even as prices fall.

If the Fed raises interest rates hig enough, holders of physical and long contracts will have to dump and buy T-Bills.

The end of the confounding contango?

This post from a couple of weeks ago noted the rise of crude oil prices to over $70 per barrel, and this subsequent post examined the unusually long contango period that has existed in the oil trading markets during the…

Hal

I can’t recall where I read it (The Oil Drum? http://www.theoildrum.com) but there is a plethora of evidence that higher gas prices cause a switch towards more fuel efficient cars, but not less driving.

UK traffic congestion continues to grow by 3% pa despite rising gasoline prices (until the petrol tanker strike of 3 years ago, gasoline taxes were escalating at more than the rate of inflation). Petrol here costs almost 1/litre ($6 per US gallon).

Less driving would require really big structural changes in society — eg more dense suburbs, living closer to where we work, more high street shopping, etc. Not likely unless the market becomes convinced high gas prices are a permanent feature *and* urban planners and developers are allowed to alter zoning to increase densities. Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) as we say, here.

Another factor is that the cost of petrol, in car ownership, is about 20% of the cost of owning a car for the average driver (again I saw a discussion on the web recently, cannot remember where — range is 20-28% of total ownership cost).

The big costs of owning a car are depreciation, parking, insurance *not* petrol.

So again, a pure price signal won’t have a big effect on driving. What seems to happen is short term it does, but in the long run, income rises and people go back to driving as much as before, buy houses further out, etc.

1/12 of cars bought here are SUV class, and of the richest part of the country (London) it is as much as 1/8. I can assure you it has been many years since I saw an unpaved road or a snowdrift in London! Granted our SUVs are smaller than yours, mostly, but still it is a measure of the degree to which the petrol price is just not an issue for many (most?) drivers.

It’s one of the reasons I think, reluctantly, that CAFE is a good idea. Because there is no way politically a price signal of the necessary size to improve fuel economy by, say, 40%, can be generated. I can’t see the US taxing petrol to $6/gallon.

CAFE with an option to trade rights between car companies is probably the best solution. If you want to make low fuel economy sports cars, you may simply have to pay another car company $2000/ unit to make those cars.

Interestingly, here in London, pure electric runabouts (built in Bangalore) are proliferating– they do about 30mph max I believe. Pace a 1k government subsidy to buy them, they cost about 8k I think (gross) ie under $13k US. And they are exempt from the Congestion Charge (8/ day) and I believe the central Council (Burough of Westminster) gives them free parking for 4 hours (Parking is about 25/day).

Very simplistic and arguably not very useful analysis, looking at little things when what probably matters is big things.

John is right, demand is quite inelastic. Yes behaviors will change, but certainly not hugely in the short term, an less so with an overly indebted American consumer especially. They might love to own the new Civic hybrid, but the math adds up that it’s much much cheaper even at current prices to keep paying at the pump than the price of the energy-saving car. Also, with a healthy economy there’ll be a healthy call for energy.

But the reason JDH’s analysis is much too simplistic is the nature of the timeframes involved. If it’s correct (and JDH makes no contrary claims) Stuart’s graph points out that peak oil may be here as regards supply. Let’s grant that for purposes of argument. Let’s also grant for purposes of argument that over the short timeframe substitutes (like shale, sands, etc) are more expensive than oil. Then the only way for prices to fall is for demand to drop. If demand for energy is relatively inelastic over the short term, then it’s a battle of timing. How soon will demand wither enough to make a difference? But in fact global demand is growing.

Unless of course we have a recession. That will indeed drop demand and probably prices. And bring a host of other problems.

But for now, Stuart works with data and JDH works with speculation. For now, I’ll go with Stuart.

John, my views overlap with yours considerably. I think that folks will hang onto “personal mobility” as long as they can, and that we have a lot of room for improvement here with our 23 miles per US gallon fleet average. (You don’t happen to know the UK fleet average do you?)

I hate CAFE, as something that should have worked buy now, if it hadn’t been broken in several important ways. I think it’s too lake to reform it, and anything that leaves the US Congress will be too weak or too late to matter.

If it was me I’d slap taxes and credits on new car models immediately. Taxing guzzlers and rewarding fuel sippers (regardless of their base technology). The political problem with that of course is that it would be the nail in GM’s coffin, and so we can’t do that either.

On a practical standpoint we will be left with natural market adjustments as “improved” CAFEs are devised to take effect long after it matters.

RN: In a general sense, you are correct. Stuart is looking at past production (up to the present). And JDH is laying out some possibilities for the near-to-middle future (e.g. the next five years). Quite clearly, that is speculation. Saying you’ll go with Stuart and now with JDH is largely meaningless because all that statement really says is that you are looking at the past and not at the future.

I’ve repeated this phrase many times on this board: I was long oil at $30, long at $50, but am not buying at $70, for some of the speculative reasons JDH mentions. The future is always speculation, so it’s a matter of laying out several possibilities, trying to determine probabilities that go along with them (by looking at the past, e.g. Stuart’s production data and past examples of elasticity), and then guessing.

My intuition all along with this whole issue of peak oil is that we will hit a peak/plateau, the price will drift upwards, and we will finally find a price at which demand destruction will take place. The world economy is strong today, but I still think imbalances are unsustainable, the end of the housing boom will place large negative pressures on spending and jobs, and the many anecdotal stories I’ve been reading about vacations postponed and spring breaks cancelled amongst those with little disposable income will broaden to reduce demand.

oh, and anybody who saw 60 Minutes last night on TV is aware of the crime of misinformation we are committing with regard to the ethanol solution.

more at the R-Squared blog

that’s just one more thing that will slow our real response.

Oil production and megaprojects

Stuart Staniford of The Oil Drum discusses the Petroleum Review’s fairly optimistic projections of future oil production based on new megaprojects coming on line over the next few years.

The executive summary is that while I think this report

…

As prices are now demand driven, we should see seasonal rises in spring and summer, falls in fall and winter, on a backdrop of increases due to growth, and decreases due to recession. More problems ahead seem more likely in the next few years as markets adjust to unstable governments, and production is as likely to decline as increase due to more intervention by these governments. Rising overall until the next recession which is probably not too many years off now. Only then will production catch up with demand leading to a supply driven market.

About drilling in the Gulf – have read that drilling rig ships are renting for $500,000 per *day* – might be more a matter of supply/demand for getting fields up and running again instead of simple “worth” – there just might not be the resources – for now – to get them pumping again.

Not unsimilar as to what happened with barges and the grain markets last fall – barges were wanted – just couldn’t be had.

I live in the Gulf Coast and agree with Jon and TR…the maintenance and construction resources are basically running at capacity…rigs, engineering companies, welders, pressure vessel shops etc.

I think the construction activity we are seeing today is more a reflection of the rationalization that occurred during the oil bust 8 years than the current prices.

Having professionally lived through several busts, I hope the industry has the discipline to maintain steady, ratable growth without getting out of control on the upside…

Oil subsidies for fishing industry?

Subsidies to reduce the impact of the oil crisis? See “Fishery layoffs loom if costs keep rising” (business, page 3) By Jon Fernquest Are oil subsidies justified? Can oil subsidies keep businesses from changing and adapting to higher oil prices?…

By the end of 2006, we should have a much better handle on the future of oil production. That one TOD graph says it all.

Demand destruction is an interesting phrase. If we have indeed peaked, the destruction may include more than just simple demand.

There are just too many problems coming at us all at onceand we have no coherent plan to address any one of them.

I am always amazed that at this critical juncture of our history we have choosen an ideologyprivatization of everythingand a leader (GW)that are the antithesis of what we need.

Does anybody remember what the gold price was when JDH posted how bad an investment gold is? 😉

Paul – therein lies the difference between a lousy investment – and a good trade….

Jon – Quite the contrary. The gold play began 6 years ago. It’s a macro investment call.

Paul – so you’re liquidating now, correct?

Some. But indeed the dollar adjustment down hasn’t even begun in earnest yet.

I’m ready to ride out some volatility, but at some point China will decide the benefits of a pegged Yuan are not worth the costs. When that decision comes everything will change, not just because of China, but because of a rush for the exits. Somewhere at the height of that chaos I suspect it’ll be time to liquidate.

Odograph

I think the UK fleet economy is around 32mpg, but that is Imperial Gallons which are 20% larger. I would have to check to give you a proper number.

The big factor here, now, is the shift to diesels, which is driving fuel economy up even though engine sizes are growing.

I keep a track of how many Prius’ I see (they get a ?8/day exemption from the London Congestion Charge, so there is a strong incentive to own one) and I have counted 3 in 2 years. However small electric cars, the G’Wiz, are going like hotcakes, at least in central London. They are a 100% battery powered 2 seater, exempt from congestion charge and with one Council, at least, allowing free parking. You wouldn’t want to be in one when a Range Rover hits you dead on, though!

On CAFE, I think it is worth a go– not economically optimal v. simply a very high gas tax, but still capable of producing real gains. My scheme of trading rights between car makers to produce fuel inefficient cars, would have similar effects to the taxes you propose.

Licensing at car in Singapore costs something like $20k, but they still have major traffic problems. Raising the entry cost of a new car simply reduces the percentage of the cost that derives from driving.

TR Elliot

The Hotelling Model of an exhaustible resource is basically a long upward sloping curve, with price on the y axis and time on the x axis. When the last unit of resource is consumed, is also the point where price rises to infinity.

That is the standard economic model. Of course, it hasn’t predicted the price of oil very well to date.

Probably because the fixed costs of finding and producing oil are so huge. So once the wells start producing, the incentive is not to adjust supply to the cash price of oil, but to produce as much as you can.

(the Saudis of course work the opposite way: they have the lowest cost oil in the world, but they have systematically underproduced, thus allowing higher cost oil producers to compete)

But the basic intuition of the model is probably correct. As the world’s supply is exhausted, prices will rise. Those price rises will bring in new, marginal sources of supply, as well as ‘backstop’ technologies like oil sands.

The prospect is therefore for great volatility in oil prices (a product of highly price inelastic supply and demand), but a general upward trend over time.

The problem for the world economy is that doing without oil is probably a 30-40 year task, at least, in terms of replacing our existing physical capital with non-oil dependent technologies.

Unfortunately we may only have 15-20 years to do it.

In which case, recession or depression is likely, as a lot of existing capital (be it cars, planes, filling stations, far flung suburbs etc.) will suddenly become uneconomic, and the ‘switching’ cost will be one of slack resources.

The latter is more or less what happened in the 70s. Oil intensive industries, and the car industry, were caught with the wrong type of physical plant for a world of expensive oil. As a result, they went into a slump, and took the whole economy with them.

It’s likely that that negative ‘supply side shock’ was what triggered the stagnation in productivity and standards of living through the 1970s and 80s.

To those who haven?t seen the loose change I will highly recommend them to spend time and see it through:

http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=-2023320890224991194&q=loose+change

I am sure the main stream media coverd the

Full Text : The President of Iran?s Letter To President Bush

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/

this how on put it:

“One day the Americans will wake up from their nightmares and rebuild the USA all over again. The White House will be turned into a museum and renamed The House of Whitewash and in it will be exhibits that detail all the evils that the USA had committed inside and beyond America. The Ahmadinejad-to-Bush letter would most likely occupy a niche in it, representing one of the many advices from the forces of good to the occupiers of the former White House who had been responsible for the anihilation of a large part of our world during the early 21st century”

Oil economics 101

Last week GM chief executive Rick Wagoner said he didn’t “expect [oil] to get to a price range when it would affect behavior.” Wagoner obviously knows as much about energy as he does about selling cars. From the (paid-subscription) Wall…