The macroeconomic implications of high oil imports

Replete with symbolism: “House Speaker J. Dennis Hastert switched to an S.U.V. last week after a ride in an alternative-fuel car.” from E. Andrews, “Conflicting Loyalties as Republicans Confront High Gas Prices,” NYT, May 5, 2006.

As gasoline and oil prices move to new nominal highs, energy has moved up to one of the top issues in Washington. Just a couple of days ago, the President had a photo-op with Congressional members on energy issues. The President was even moved to ask for authority to raise CAFE standards (without any statement on whether he would actually raise the standards if given the authority).

Of course, none of the actions he has forwarded would actually have a substantial impact on oil imports in the foreseeable future, as I noted in this post on the State of the Union address and tackling oil addiction.

The macroeconomic benefits of reduced energy dependence are well known. Increases in oil prices would then have less of a contractionary impact on aggregate demand (via imports). Reduced energy intensity (i.e., using less energy per unit of GDP) would mean that oil price increases would have less inflationary impact on the economy (even for a constant degree of monetary policy credibility, if the effective capital stock is sensitive to large changes to the relative price of energy).

But there is another reason to desire less dependence on foreign energy sources: the energy dependence has been an important force in driving global current account imbalances ever larger. As discussed in a new IMF report on the Middle East and Central Asia Regional Economic Outlook, reserves (mostly in dollars) are increasing rapidly.

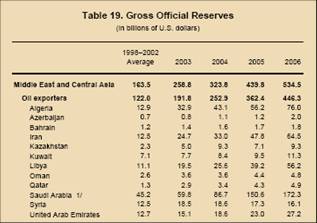

Table 19 from IMF, Middle East and Central Asia Regional Economic Outlook

The table indicates that the region’s oil exporters’ reserves have will have risen by about $250 billion from 2003 to 2006. Note that these figures do not include Russia’s reserves (which is outside of the region; similar numbers can be obtained for up to 2005 in the Treasury’s recent paper on petrodollars). This accumulation is partly due to the low proportion of spending of incremental petroleum revenues.

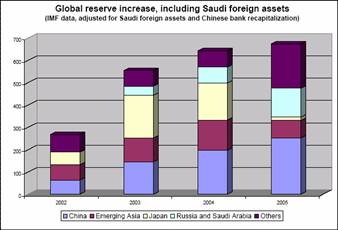

In fact, reserve accumulation by Russia and Saudi Arabia alone has now become a much larger share of increases in reserves. Much of the “other” category would include the reserves of the MidEast oil exporters, as shown in this figure drawn from Setser and Ramaswamy’s RGE Reserves Watch.

Figure 1: Setser and Ramaswamy, RGE Reserves Watch

Since most of the reserves are held in dollars, this has tended to depress yields on Treasury securities, thereby extending the spending boom in the US and spurring elevated levels of imports. Of course, this is not the first time this observation has been made; Brad Setser has made similar observation on a number of occasions, as have other documents (e.g., see the IMF’s World Economic Outlook chapter on oil). But it is worth stressing that China and East Asia are fast declining sources of dollar accumulation, proportionately speaking. This means that faster Renminbi appreciation, desireable as that would be, will not be enough in and of itself to resolve global imbalances; action on both the energy and fiscal fronts are necessary as well.

So in addition to making the US economy more susceptible to energy shocks, the disdain the Administration has had for energy conservation (remember Cheney’s views) has added to the forces distorting the world macroeconomy, placing us in the situation we now confront: intransigent global imbalances and our fortunes held hostage to state actors abroad. (Note that the figures reported above do not include accumulation by the government and quasi-state entities not directly involved in monetary policies, but Feldstein has highlighted as additional non-private-sector actors in the current situation).

Technorati Tags: href=”http://www.technorati.com/tags/oil+addiction”>oil addiction,

gasoline tax,

foreign exchange reserves, and

Middle East, and

Central Asia

I’m glad to finally have a glimpse of the RGE Reserves Watch subscription content. It graphically depicts just how much the Gulf oil exporters are stashing away as of late.

As an aside, Hastert needs a Prius (but whether he’ll fit is another matter as he appears to be, from the picture, what an old professor euphemistically called a “man of substance”).

These numbers don’t seem to include the vast accumulation of assets by Norway’s special oil fund. Norway, which is the world’s third largest oil exporter after Saudia Arabia and Russia, have a budgetary rule which says the budget should be balanced excluding oil revenues. Oil revenues are put in a special oil fund whose assets (composed of foreign equities and bonds) are now worth some $250 billion and growing fast, both because of the $50 billion a year in oil revenues which are put there and because of the rising value of the foreign equities it holds.

Tis true, they don’t include Norway’s special oil fund or Kuwait’s investment authority or Abu Dhabi’s investment authority or the various investment vehicles of Dubai and Bahrain. They do include Russia’s oil fund, b/c Russia’s oil fund is on deposit at the central bank and shows up in Russia’s reserves.

Menzie — nice post. Hassert and RGE rolled into one.

I have to disagree with some elements of this analysis. First, although I know it is not the main point you are making, I object to your paragraph beginning “The macroeconomic benefits of reduced energy dependence are well known.” This paragraph can be reworded and will apply just as well to practically any commodity:

“The macroeconomic benefits of reduced rubber dependence are well known. Increases in rubber prices would then have less of a contractionary impact on aggregate demand (via imports). Reduced rubber intensity (i.e., using less rubber per unit of GDP) would mean that rubber price increases would have less inflationary impact on the economy (even for a constant degree of monetary policy credibility, if the effective capital stock is sensitive to large changes to the relative price of energy).”

Likewise you could say the same thing about copper or zinc or sugar or anything else. Ultimately, production process require inputs. Sure, it would be great to reduce the inputs and make things out of thin air. But that’s not going to happen.

Commodity prices change all the time, and yes, when something gets more expensive, we need to try to use less of it. This is a natural adjustment that happens through the market system. Do we need CAFE standards for this? Is that really the problem? If so, why don’t we need the equivalent of CAFE standards for copper or rice or textiles? Why can’t the market be trusted to choose energy inputs for cars, but can be trusted to choose zinc inputs for cars? Would the country really be better off if the government set efficiency standards for optimal use of every single commodity and production input? I don’t think so.

In short I think the above “macroeconomic argument” is fundamentally misguided if it is taken to mean that the government should be setting energy efficiency standards. On its face it can be used equally to justify government intervention in every element of the economy, and we know how badly that works out.

I also have a complaint about the main point, the supposed horrors of growing petrodollar reserves, but I will put that into a separate message.

With regard to the petrodollars, you have some good data and insights regarding the effects of the massive increase in spending on energy resources and associated money flows. If oil exporters are not spending their money, they are investing it, and much of it ends up being lent back into the U.S. What are the bad consequences of this?

“Since most of the reserves are held in dollars, this has tended to depress yields on Treasury securities, thereby extending the spending boom in the US and spurring elevated levels of imports.”

In short, this is leading to economic prosperity within the United States and the West in general! Now obviously there are problems and you are right to point them out, but at the same time let’s not ignore the silver lining here. Economic prosperity is a good thing, and the U.S.’s appetite for imports has helped to raise Chinese peasants out of a starvation level of income. These trends are arguably highly beneficial for the welfare of people all over the world.

I understand the worry that the situation is unstable and is poised for collapse. But nobody knows for sure that will happen. There is still hope that things can unwind gently.

Characterizing the accumulation of petrodollars as a terrible thing requires the assumption that the unknown future consequences of current monetary flows will be disastrous. But we don’t know that. What we do know is that the actual, visible impact has been positive so far, increased prosperity for both wealthy Western nations and fantastic economic growth for countries like China and India.

“The macroeconomic benefits of reduced energy dependence are well known. Increases in oil prices would then have less of a contractionary impact on aggregate demand (via imports)…”

Just wanted to point out, as an implication of your remarks on reserve increases, that it is not clear that high oil prices are a net drag on US aggregate demand. Oil producers sell to the entire world, but lend primarily to the US. On a cash flow basis, that means it’s possible that the US receives more incoming funds in the form of debt purchases than are drained as payments to oil producers for every dollar increase in the price of oil. If this is the case, then the contractionary impact on aggregate demand of a hike in oil prices might be more than offset by an expansionary effect via the “capital account surplus”.

The title ought to read “The macroeconomic benefits of reduced oil (or hydrocarbon) dependence….”

Energy does the work instead of humans. Without energy we would have nothing-no lights,computers, airplanes, you name it. We would all be manual laborers or farmers. Energy allows people to live a better lifestyle than they would without it. So to be dependent on energy means a higher standard of living. There’s nothing wrong with being dependent on energy,if one wants a better standard of living.

Being dependent on a depleting source of energy located in a hostile part of the world is another matter.

Hal:

You’re deluding yourself. For the current account imbalance to be benign, the excess dollars must actually be invested. This means they must be placed productively. Trillions of dollars of government securities don’t count.

Read about the “Pitchford Thesis”. The distinction is lost on most apologists for the status quo.

Hal and Jim Miller: Of course, one could logically make the case that any input dependence would be better reduced. But that is an analogy with little relevance. Consider natural rubber; there are substitutes, where the degree of substitutability is fairly high. Such does not apply to oil. Then the degree of intensity is also much higher for oil. I bet that for any of the other commodities you can think of, the amount of the economy tied up in its consumption or transformation is much less.

But I get your point that each commodity should be used up to its marginal cost equalling its marginal benefit. In a freely operating competitive economy where the first and second welfare theorems are relevant, you’re right. My point, perhaps too colloquially put, was that there is a negative externality to oil imports and perhaps oil use, due to macroeconomic concerns. (This is aside from environmental concerns, which provide another channel for arguing for taxes on energy consumption).

Suppose aggregate demand and aggregate supply is perturbed by shocks from energy prices. (If anybody is curious, I’m using the model laid out algebraically here, with an additional net export factor added to the AD curve). In re: Steven Waldman’s point, aggregate demand is usually modeled as being reduced by energy shocks because increases in energy prices for the US constitute an almost pure transfer abroad to agents with a lower propensity to spend on US goods than US residents have — e.g., Keynes on the the Versailles treaty and the IMF report cited in the post. The aggregate supply schedule is shocked upward.

Finally, append to the standard model a social welfare function that says welfare is decreasing in output and inflation variation around target levels — say with quadratic penalty. This would mean actions that reduce variability (coefficient on net export factor in the aggregate demand curve, and the magnitude of the Z factor — itsef a function of oil’s importance in the production process — would enhance welfare. Of course, in the real world, one would trade off the benefits of reduced variability against the cost of affecting the coefficients. So as always, one would want to balance marginal benefits against marginal costs.

Dr. Chinn — First, thanks for a very fine blog, and for taking the time to respond. Although I agree that an energy shock is usually (and quite properly) considered a drag on aggregate demand, I think we live in interesting times. True, oil exports represent a transfer of wealth abroad to agents with a low marginal propensity to spend in the US.

But I think a simple Keynesian model breaks down here. In a normal system, we would get the normal nightmare — low marginal propensity to spend, high marginal propensity to save, but nothing profitable to invest in because of low aggregate demand. But what if agents with a low marginal propensity to spend “invest” by lending wealth to those with the highest marginal propensity to spend? This is stupid, on the one hand, because lending to agents who consume rather than invest is likely to lead to defaults. But, if these pseudosavers do “invest” in this way, the net effect of an energy shock is transfer of wealth to those with the highest marginal propensity to spend! And if the same pseudosavers receive transfers from the entire world, but “invest” by lending primarily to those Americans with the highest marginal propensity to spend, an energy shock becomes net stimulus to the US economy in particular!

I know this is unusual. But is it wrong?

Steve Waldman: Interesting viewpoint, and stranger things, no doubt, have happened. But each time there is a positive oil price shock the transfer effected from the US and rest of the net oil importers to the oil exporters is a “real” one. The lending of financial resources by the oil exporters to the US is a temporary transfer of resources that should have net present value equal the amount loaned. In other words, US spending should be affected only to the extent that credit market distortions exist, there’s a bubble (or for some reason, Americans don’t expect to have to pay back the loan in its entirety). So I see your point, but I don’t think this can be a general characterization of how the shocks will play out, even if it looks like it’s got some relevance to the current situation.

Stefan Karlson — do you have a source for the size of the addition to the Norwegian oil fund. Tis relevant for something I am working on. Thanks. Brad Setser

It was not the administration’s disdain for conservation which caused a five year delay in the passage of an energy bill. Neither did it cause the Congress to write such a bad bill. Cheney’s view was and is correct. American cannot conserve its way out of the current situation and alternatives are still years away from making any significan contribution to the country’s energy supply. People should have listened when he said it all those years ago. The benefits of energy independence are endless, and need not be listed. Now, there is a need to hurry to develop sources of the old fuels while alternative are developed at the same time. It will take all approaches.

when you want to heat your home, drive to work, or run your company, you have two choices: you can improve efficiency, or you can buy more (or alternate) fuel.

the number i’ve heard thrown around is that efficiency is cheaper than any alternative. the ROI is better. that’s the reason companies (with steely eyed accountants) are ahead of consumers on conservation. they run on numbers more than emotion.

now, keem, if you want to say “hurry to develop” why don’t you pad that out for me? do you have a contender that actually has better ROI than efficiency?

odograph, I assume there is something to conserve or companies would have no energy with which to operate. One can conserve so much, but that will never be the total solution. If sources and uses of oil, natural gas and coal cannot be found or alternatives are not developed the lights go out, and you can quit worrying about conserving.

it is the nature of natural resources that their supply tails off, and does not switch off in a binary fashion.

we are on “lifeboat earth” and somewhat blessed, really, that all the supplies are not equally accessible and consumable.

if we think of things in broad historic timelines, it becomes apparent that we are facing a resource pinch, and conservation will make that pinch easier, as we figure out what comes next.

And conservation alone will not solve the problem.

why do people first argue against conservation, and then when that fails, fall back to “conservation alone?”