It didn’t look to me like a bubble on the way up, and it doesn’t look to me like a bubble on the way down.

First, let me define terms. I think of a price bubble as a market outcome in which the price rises for no reason other than the fact that everybody expects prices to keep going up. The first problem with that as an interpretation of the recent behavior of U.S. real estate prices is that surely it is clear to everyone by now that real estate prices have stopped going up. So, if expected price appreciation was the only thing propping up the market, we should now be seeing a calamitous price collapse rather than the slow fizzle that’s unfolding.

A second problem I have with the bubble story is that, as seen in the graph below (originally presented here in June 2005), there was substantial variation across U.S. communities in the amount by which real estate prices went up. If buyers’ expectations of price appreciation just appeared of the blue, how did they happen to come out so differently across different communities? These differences in realized price appreciation were at least weakly correlated with such fundamentals as population and employment growth.

|

Third, if this was all a bubble, then what we should be seeing now is a reversal of that process, with the states that are brightest purple in the graph above now taking the hardest hit. But, as Felix Salmon observed, if anything the opposite appears to be the case: the states that are now experiencing the highest mortgage delinquency rates are the ones where the previous real estate appreciation had been the most modest:

|

Indeed, when one calculates an ordinary least squares regression of the 2006:Q4 mortgage delinquency rate for state i (denoted di) on the 2001-2005 price appreciation (denoted pi) for the 48 contiguous U.S. states, the correlation turns out to be negative and quite statistically significant (t-statistics in parentheses):

|

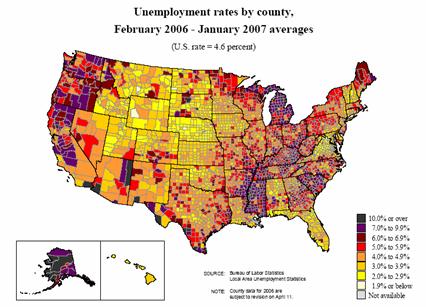

Why would states that had the smallest real estate price gains be the ones that are now having the biggest problems? I couldn’t help noticing a similarity in the appearance of both the above maps with the current distribution of unemployment rates across the U.S.– areas with higher unemployment today tend to be those that saw the least price appreciation and the most mortgage delinquencies.

|

Indeed the correlation between the state unemployment rate and state delinquency rate is positive and highly statistically significant:

|

So all of this looks to me to be consistent with the story I was telling two years ago, according to which the housing market, on the way up and on the way down, has been driven by fundamentals. Low interest rates and rapid population and employment growth relative to the supply of available housing were the main factors driving house prices up, and the reversal of those will be the main thing causing real estate prices to come down.

The one thing to which I think I was not paying enough attention two years ago was the role of lax credit standards and even fraud ([1], [2]) in addition to low interest rates as factors fueling the boom. I have been coming around to the view that there may have been some significant market failures behind that. My first worry here is about Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the second concerns whether some of our institutions have the right incentives for fund managers to properly value lower-tail risks. This ready availability of credit, over and above the low interest rates themselves, I now believe was an important factor contributing to the real estate boom.

Now, this may be how many in the “bubble camp” have been interpreting the phenomenon all along, and it is not my intention to engage in an argument over pure semantics. But I believe there are some conceptual and predictive differences between the notion of a “bubble” as I defined it in the opening paragraph and the alternative description of events that I just offered.

First is the question of whether the price appreciation of the last five years will be reversed on a community-by-community basis, with the biggest problems necessarily appearing in those communities that previously had the biggest price appreciation. The pure bubble explanation says that they would, while the market fundamentals story says that they will not.

Second is the question of what we can or should do about it. If prices can go to any arbitrary values for any arbitrary reason, then I am not sure what to propose in the way of policy recommendations. But if the price run-up was the result of a specific market failure, then correcting that market failure seems like something that should be getting everybody’s attention.

Bubbles? Bubbles? I see none. Toil and troubles? Could be plenty.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

housing,

bubble

I fear that “bubble” and “credit crunch” and “globalization” and lots of other terms that are used as short hand for a complex set of conditions more often than not obscure the issue under discussion. If one asserts that there is a credit crunch, without first defining what one means by credit crunch, then no real information has come out of one’s mouth. Same with “bubble.” You have defined bubble in your own way, and that is good, but you may not have answered the bubble crowd because they may be using a different definition, or no particular definition.

If evidence that a bubble existed would be a rise in defaults in the hot markets, that’s fine, but observing that there has been a rise in defaults in a non-hot market does not serve as evidence against a bubble. It is irrelevant to the issue. If a bubble advocate argues that defaults in areas that have enjoyed no unusual rise in prices represent evidence the bubble has popped, one can say it isn’t so, but that is as far as it goes. Midwest defaults are not evidence in either direction.

JDH,

Having looked at the state-by-state delinquency data for Novastar and New Century — both subprime lenders — I can tell you that in late 2005 you didn’t need a regression analysis to conclude delinquencies were inversely correlated to unemployment.

The situation changed dramatically during the course of 2006. California in particular went from negligible delinquencies to above-average in a space of three quarters. The inverse delinquency relationship simply broke down, and that is what took the writers of CDS insurance by surprise. The same is likely happening Alt-A. Together these accounted for about a third of national mortgage issuance.

Bottom line: the most recent experience in California is telling us that delinquencies are more correlated with lending standards than employment. This, of course, is consistent with “bubble” explanations of HPA. The factor that regression models don’t take into account is this: there is a binary relationship with lending standards. As they are falling, they are positively correlated with losses/delinquencies. When they are rising, they are negatively correlated. Logic tells us that this should be so.

A couple of comments:

Obviously using state-level data masks considerable regional variations. Take New York State–the housing market in the five boroughs and suburban counties obviously bears little relationship to the depressed conditions that prevail elsewhere in the state. I wonder if any trends have been missed.

Second, another possible reason why the areas with the most price appreciation also have lower delinquency rates is that in a sellers market, there is less reason to turn to buyers that would require exotic financing, as an ample pool of well qualified buyers is competing for the same housing. This would further support the fundamentals hypothesis.

With that in mind, I find it somewhat ironic that the markets where land use regulation suppresses housing production (say, New Jersey) will weather the housing slump better than those where demand better expanded to meet supply (say, Texas?). Talk about perverse incentives.

JH said: “The one thing to which I think I was not paying enough attention two years ago was the role of lax credit standards and even fraud ([1], [2]) in addition to low interest rates as factors fueling the boom…”

I don’t think those factors had nearly as big an impact on the housing boom as is widely believed. This is a letter from NACA (National Association of Consumer Advocates) to lawmakers/policy makers regarding the problems in sub-prime lending.

http://209.85.165.104/search?q=cache:mOITQUrDRLUJ:www.naca.net/_assets/shared/633081903109944364.doc+5+year+subprime+ARM&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=3&gl=us

Here is the part that caught my eye: “…Moreover, the loans in the subprime market are typically debt consolidation refinance loans and do not create new homeownership opportunities…”

What this says to me is that you’re absolutely right when you say that housing wasn’t in a bubble before and isn’t in a bust now. The housing markets were and are being driven by the fundamentals of population and employment growth. The current sub-prime lending problems aren’t strictly related to housing prices, but to mortgage size and debt servicing, not the same issues. A subtle point, but a critical one, IMO.

The homeowners with sub-prime loans that are being foreclosed on now already owned homes purchased at lower prices with mortgages that they could make. Where they got into trouble was when they re-financed and rolled-in their other debt into new, larger mortgages (or cashed-out their equity).

The difficulty these homeowners face is real, but it’s clearly not the same conditions that occur around recessions when rising unemployment forces a far broader group of homeowners into selling their homes at whatever price they can get because they’re unemployed.

“The fundamental things apply, as time goes by.”:) No housing bubble, no housing bust, no housing-induced recession. I don’t think any sweeping policy changes should be made or need to be made.

Sebastian

You compare rises in prices with mortgage delinquincies to conlcude there was no bubble. Wrong comparison. Try looking at bubble areas where prices are now falling. For instance, from CNN/Money YOY price change (source NAR):

Palm Bay-Melbourne-Titusville FL (-17.0%);

Sarasota-Bradenton-Venice FL (-18.0%);

Cape Coral-Fort Myers FL (-11.7%);

Reno-Sparks NV (-8.9%);

Barnstable Town MA (-7.8%);

Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Miami Beach FL (-6.2%);

Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk CT (-4.9%);

San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos CA (-4.5%);

Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville CA (-4.1%);

Prof Hamilton –

Michael Palumbo (Board of Governors, head of the Flow of Funds) and I have written on this topic, and when we report our results to others, their intuition about the housing boom has changed.

The paper is forthcoming in the Journal of Urban Economics, and can be downloaded here:

http://morris.marginalq.com/2007-02-Davis-Palumbo.paper.pdf

If you think of housing as a bundle of land and structures, Palumbo and I argue that the the structures are elastically supplied, but land (really, location) is not. That is, a shock to demand causes land prices and thus house prices to increase. Restated, if housing in the United States was all mobile homes on valueless land, then a shock to demand would result in more or bigger mobile homes, but (assuming no adjustment costs in production) not necessarily a change in the price of mobile homes.

Thus, it seems important to try to measure changes to the price of land to understand if an area has experienced a sizeable demand shock for housing. Palumbo and I do just that: We measure the price of developed land containing a residential structure in 46 U.S. cities starting in 1984, and find that almost every city in our study has experienced a sizeable and pronounced increase in the price of its land starting in 1999. The appreciation of land since 1999 is a continuation of a trend that Palumbo and I show began in 1984.

(Jonathan Heathcote and I show, in a different paper, that in the aggregate, land has been appreciating at a real rate of about 5 percent per year since 1950.)

The finding that land everywhere is appreciating rapidly argues against the notion that the boom was a “coastal” boom. In fact, the appreciation of residential land over the 99-04 period in places like Minneapolis, Milwaukee, and Houston was of the same order of magnitude as New York, Boston, and San Francisco.

The reason that comparisons of house prices across metro areas do not yield identical comparisons of land prices across the same areas has an easy intuition. Think of a house as a portfolio of land and structures. In areas where the portfolio weight is high on land, house prices and land prices should increase at roughly the same rate. In areas where the portfolio weight is high on structures, house prices and structures costs should increase at roughly the same rate.

The reason we are able to identify that land prices increased rapidly in many cities in the Midwest is that, in 1998, the portfolio weight on structures in many midwest cities was quite high (and the land weight quite low). So, a-priori, we would have expected house prices to track construction costs. The fact that house prices significantly outpaced construction costs in those cities is directly informative about appreciation in land.

Feel free to email etc. I enjoy reading your blog.

“So, if expected price appreciation was the only thing propping up the market, we should now be seeing a calamitous price collapse rather than the slow fizzle that’s unfolding.”

I’m not sure. Even liquid-asset bubbles sometimes take years to deflate, and housing is not a particularly liquid asset class. If houses were traded on the Big Board with continuous quotes and fraction-of-a-second execution, the picture’d be quite different. Obviously.

Small Investor Chronicles

“…if this was all a bubble, …[we should the most delinquencies where the prices rose most] … [but] states that are now experiencing the highest mortgage delinquency rates are the ones where the previous real estate appreciation had been the most modest”.

You seem to fail to consider:

(a) that in the current high-delinquency states prices might have been falling in the absence of the bubble forces, so that even nominally modest appreciation was in relative terms a bubble,

(b) when combined with falling interest rates even that slight appreciation enabled some hard-pressed people to use cash-out refinancings and HELOCs to stay temporarily afloat, and

(c) that in the states with high appreciation, cash-out refinancings and HELOCs could be used to leverage purchases of “investment” homes, and prevented slowdowns in the local economies.

Of course the relative strengths of the underlying economies set the “baselines” above which the bubbles rose and influenced their relative intensity, but that doesn’t mean they weren’t bubbles. A bubble rising from the ocean depths is still a bubble, even though its absolute altitude is negative.

Denominating Housing prices in terms of Gold also paints a no-bubble picture:

http://investmenttools.com/median_and_average_sales_prices_of_houses_sold_in_the_us.html

The real story seems to be the dollar which lost a good deal of its value in the 2000s.

Bad link in the above. Try:

http://investmenttools.com/images/re/re_div_gold.gif

No one buys houses for gold. No one gets paid in gold. I’m for honest money as much as the next guy, but this is the reality. Comparing prices of different assets maybe interesting and even useful, but it does not stand scrutiny as a yardstick in a dollar-denominated world.

Small Investor Chronicles

Full Ack.

I consider this whole thing much more to be a credit bubble than a price bubble.

Prices are “somewhat elevated” 😉 but the credit side looks horrendous.

And I’m not sure that the effects of a blasting credit bubble are any better than the effects of a blasting price bubble …

Your resistance to acknowledging the housing bubble is quite interesting. Just a few weeks ago I went back and looked at a few of your 2005 posts on the issue. After this post, you are now part of my contrarian indicator. The day you accept that there was a housing bubble, I will be a significant day closer to becoming a real estate investor.

First, the flaw in your bubble definition is to assert that a disconnect between values and fundamentals can only occur when values are rising – you choose to ignore the fact that fundamentals can deteriorate. Given the continued depopulation of the Midwest, as well as the difficulties of the manufacturing industry, it may well be the case that the disconnect between fundamentals and values of housing are larger despite the relatively stable prices than in areas where prices rose faster.

See this recent Reuters article about Detroit http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,259907,00.html . Like your chart above notes, housing prices in Detroit barely increased over the past couple of years. Note this quote “Steve Izairi, 32, who re-financed his own house in suburban Dearborn and sold his restaurant to begin buying rental properties in Detroit two years, was concerned that houses he thought were bargains at $70,000 two years ago were now selling for just $35,000.” $70k to $35k is pretty drastic. Even more eyeraising are these quotes ” With bidding stalled on some of the least desirable residences in Detroit’s collapsing housing market, even the fast-talking auctioneer was feeling the stress. “Folks, the ground underneath the house goes with it. You do know that, right?” he offered. After selling house after house in the Motor City for less than the $29,000 it costs to buy the average new car, the auctioneer tried a new line: “The lumber in the house is worth more than that!””

A more data driven challenge to your analysis is how do you account for oversupply. If a builder builds a home for $100k, expecting to sell it for $150k, and can’t even get a rustle up a buyer, where is that going to show up in your data analysis. In affect the builder is buying a home for $100k, and can’t sell it. Isn’t the value of the house $0, and the loss 100%?

I don’t know why you have a bias against accepting that there was a housing bubble and that it is bursting, but as a human being and thus very reliant on experience, I can see by DT’s data that your community hasn’t yet felt the pain. But you will, as we all will soon enough, just like the people of Detroit are, Cleveland http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/23/us/23vacant.html?_r=1&oref=slogin, and Sacramento http://flippersintrouble.blogspot.com/index.html

Thanks for you great blog!

Alex,

Why do housing bubble vigilantes always get so emotional? 🙂

I think it is quite reasonable to use Gold as an unbiased proxy for the general price level. Using it that way obviously paints a far different picture than simply looking at nominal housing prices.

Again the big story doesn’t seem to be the so called “housing bubble” but rather the dollar loosing a good chunk of its value.

egghat,

Fair enough! If it was (is?) a credit bubble its hard to argue that it has already burst.

Professor-

Seems like a post expressing doubt about the housing bubble draws comments similar to those where doubt about peak oil is voiced (although somewhat smaller in number). There is a faction that loves bad news, and absolutely salivates at any perceived economic crisis.

JDH,

Great analysis and right on target. Thanks for the regression analysis, econometrics used properly to support the facts rather than “create” the facts. Also, you certainly did make the “bubble” proponents cringe.

Fullcarry,

Spot on! Your gold analysis runs parallel to the analysis of JDH. It is sad that there are so many reasonably intelligent economists who are blind to the role of gold.

Fullcarry, I didn’t mean to sound emotional. What I’m trying to say that this cannot be adequately explained by the dollar/gold ratio. Salaries did not grow with the gold, and salaries are what, in the end, pays for houses. Houses kept appreciating like mad in the fist half of 2005 despite dollar strength, and are depreciating in 2006-07, despite dollar weakness.

Perhaps the more correct term is asset inflation.

People using the housing market as a way to “get ahead” and as an ATM machine to spend money they don’t have as housing prices were forced upward by loose credit standards.

When I saw friends buying houses as their “retirement investment”, I knew we were in big trouble.

DickF

Check out economist Michael Darda. He uses Gold extensively in his models.

Alex,

I am not suggesting housing is affordable at current prices. I just don’t think the bubble label fits what actually happened the past 5 years.

And keep in mind after a currency devaluation prices don’t all adjust at the same time, salaries always lag. In fact we are starting to see wages catch up. 2006 saw the largest increase in wages since 1999.

Excellent perspective. Thanks. The Fed funds rate post dot-com was a repeat 1929/1930. Even a the 0 cost of capitial, housing was in the tank ’till 1934-5 and foreclosures were the norm [“George, we lost the farm”]. So whats different now? Good employment prospects kept people happy and available to take on risk [George, were only gettin’ 1.5% interest in our savings account]. So, with a good job as back up, folks started to look around for mays to make more interest/return on their capitial. Add to this lax lending practices and Wall Street’s need to generate fees – presto, instant money [George, leave our money in the Bank and we get a no-money down mortgage and go into the property business – we are gunna make a killin’]. The Fed has mentioned that in some of the markets where there has been the greatest price appreciation, up to 40% of the RE purchases were by investors, guys named George.

In a brisk market, any brisk market, it is easy to make money. Not so in a slow market. And, it is investors (not necessarily “homeowners”) that are quick to jump ship if the headwinds are too strong. I think 2006 was a investor-led retrench in the housing sector even though the paperwork might read “Owner Occupied”.

My fear is the collateral damage that is left in the wake of this investment bonanza. Homeowners getting depressed ’cause the home may not be the retirement nest egg. Remember,in 4 years the boomers start moving out of the workplaces in droves causing less demand for houses). Homeowners who used their home as an ATM or to consolidate debt and signed onto risky mortgages in the refi process (causing credit/savings/spending contraction so to come). And, potential new homeowners who will get caught in the tightening lending standards and the Dream is stalled a few years.

So, if we cant call it a bubble maybe we can call it a correction – as in the stock market correction of 1929 – which actually took 3-4 years after the infamous three day long shock on Wall Street and the next 38 years to break even.

So two bright spots on the horizen: the US will now accelerate immigration (new homeowners on the way); and a little infaltion (assets improve); and lenders/investors will be a bit more humble (writing off losses unlike Japan’s silly banking rules which depressed, for 17 years, the RE market); a God forbid more Government in the mix to help out the situation.

Oh, it’s a bubble alright, Professor: price-to-income way out of whack, price-to-rent way out of whack. Prices up for no apparent reason.

It appears to be confined to locales, when I look at the OFHEO data; yes to a bubble in California, no to a bubble in Texas.

Things will be interesting as the year progresses and as more ARMs reset. I’m guessing that price reductions will accelerate here in California, San Diego, and La Jolla.

Fullcarry,

A few years ago before MKM Darda and I were debating just these issues with some others of like mind (Mike Churchill). Mike is a great analyst who does understand gold, though he has at times drifted a little he is usually spot on.

Glad to see someone of like mind posting here.

“I think of a price bubble as a market outcome in which the price rises for no reason other than the fact that everybody expects prices to keep going up.”

I don’t think this really characterizes at least my view of what has been happening. A bubble starts for some fundamental reason. In particular, there are genuine and good reasons why California (with core competence in designing computer products, movies, etc) has been doing better than the Midwest (overly dependent on physical industrial production that is not cost competitive with Asia).

But the point of a bubble is that it keeps going past the point of any sense, because people get used to the environment in which prices are going up and start to make decisions that don’t make any sense except in that environment. I don’t need to perform a regression to know that paying $5000/month to buy a house in San Francisco that I can rent for $3000/month makes no sense whatsoever, unless I believed that prices would always go up in the future. I could (at least until recently) have gotten some interest-only/negative amortization creation that would have allowed me to “buy” the house for $3000/month. But that would carry far larger risks to me than just renting it, and only has advantages in a world in which prices keep going up. And lenders made many decisions which worked great until prices stopped going up, and now don’t look so great. I think the fallout of that risk repricing has only just started. In particular, we are not yet in a position to observe the effect of the contraction of subprime credit on the house sales statistics, but no doubt that effect is going to be negative and significant, that in turn is going to create some further negative pressure on house prices, which is going to further weaken the credit quality of other recent loans. I don’t think we know how far these feedback processes are going to go yet.

History teaches us that house prices are very sticky. People resist selling their house for prices much less than what the person down the street got six months ago. So house prices only descend rapidly when there is enough economic carnage to force people to sell (as there is in the Midwest, but not, at least not yet, in California). Here in California, prices are now floating down very gently (in real post-inflation terms). I anticipate this continuing for years, till the point where it actually makes sense to buy houses again with a sensible mortgage (like a 30 year fixed with 10% down). Right now, any renter planning to buy a house is seriously misguided.

I also think one shouldn’t neglect the sentiment. In the last few years houses turned from a roof over one’s head to “the best investment”, “always goes up”, “they ain’t making any more of it”, etc., ad nauseum. I am waiting for houses to be called “money sinks”, “worst investments” and other such nasty names. Then the “bubble” will be truly over.

Small Investor Chronicles

Alex,

A few things.

The dollar began recovering from a serious deflation in the latter half of the 1990s. Moving into Y2K Greenspan ran the dollar down past the equilibrium point and the foundation was laid for inflation.

Y2K was a joke but the FED took it seriously and overreacted by injecting a lot of money into the system. To counter their error, in mid-2000 (beginning around April) they began pulling a lot of money out of the system. The whiplash of deflation to inflation back to deflation pushed the economy into recession. They could have prevented the recession right up until the spring of 2001 by lowering interest rates but Greenspan held firm because of his fears of inflation.

Bush was elected and attempted to jump start the economy with a tax cut, but it was a Keynesian demand side tax cut rather than a supply side tax cut (a clear demonstration that Bush did not understand supply side economics) and the economy continued to groan.

Thankfully Rep. Bill Thomas got involved and created a powerful supply side tax cut which Bush signed in 2003. The economy immediately responded and has continued to react positively.

But right now the future is uncertain. The FED is once again attacking the economy with increased interest rates in a futile attempt to hold down inflation, and the Democrats are in the process of dismantling the tax cuts that have given us our recovery. It is possible that the FED and the Democrats will attack the economy in tandem and send us nose-diving into stagflation and another recession.

I am actually a little more optimistic. Bernanke has given some signs of acting responsibly and I am hoping that the Democrats get so frightened by the polls that they repent of their tax increase rhetoric.

Finally understand that wages are a lagging indicator. With the lowering of interest rates wages actually do not have to go up to drive up prices. A family making $50,000 will have the same house payment but a lot more home at 4% than at 8%. This is why I say that the comments of JDH and Fullcarry are complementary, increased home prices from lower interest rates and other fundamentals (JDH) and inflation (Fullcarry).

Well,

1. The idea that it was the tax cuts that drove the economy is interesting, but it is just an opinion, not a fact. I agree with Dr. Hussman that it was the massive government spending that did the trick. Aside from the fact that a tax cut without a spending cut is a lie.

2. Yes, a given house will sell for the higher price at a lower interest rate. Until the rates go back up. This wouldn’t be a concern if those mortgages were traditional 15 or 30 y. fixed with 20% down. They are not. The pain is just beginning.

3. Supply side economics is fraud. If Mr. Laffer could quantify at which level of taxation the revenue is maximized (and obviously the point is dynamic), there would be at least an attempt at credibility; otherwise it is not worth the napkin he drew it on.

Small Investor Chronicles

I think your ‘fundamentals’ theory has a big hole in that it is not ’employment’ per se, but INCOME (along with AFFORDABILITY or CREDIT availability) that is relevant to housing prices.

Even in near full-employment areas like NoVA where I live, houshold income has hardly gone up anywhere near the levels needed to justify the huge price rise. You can have areas in Florida, for instance, where there is near-full employment at what MacDonald’s pays.

A serious economist has to look at the disposable income as well as savings and other assets of an area. And more importantly, psychology.

That precise data on such things are hard to obtain is not a valid reason to explain it ‘away’ and ignore market ‘manias’, which is part of human nature in general, but more stark in capitalist societies.

Your hedgehog-like insistence on the ‘no bubble’ theory is not compatible with your academic position–just as a believer in God can never be a genuine scientist, a person who explains ‘away’ the bubble in terms of ‘fundamentals’ can never be a genuine economist.

You’re missing two big variables: time and space. (Can’t get much bigger than that.) The bubble begins at the center — of a graph of value, not the country. The center is in this case the coasts — NY, CA, FL. The bubble reaches its highest levels in these markets. But the bubble eventually makes its way to the periphery — in this case, the center of the US — OH, MI, MO, etc. The process then reverses itself. The declines begin at the periphery (of value) and work their way to the center. That’s why time is so important — the process has only just begun and is only visible at the periphery. It be will many months before it is obvious in NY and other core locations.

TedK said: “…Even in near full-employment areas like NoVA where I live, houshold income has hardly gone up anywhere near the levels needed to justify the huge price rise. You can have areas in Florida, for instance, where there is near-full employment at what MacDonald’s pays…”

It seems to me that there’s a fatal flaw in the argument that “housing is too overpriced to be affordable, so high housing prices are unsustainable.” It doesn’t explain what’s happening in housing. What DID cause the huge price rise, if no one could afford those houses and no one was paying those prices? The price of a house isn’t just what the seller says it is, it’s the price the seller and the buyer agree to.

People in the middle- or lower-income strata may be priced out of housing, but there are clearly other people that aren’t and they’re the ones that can “support” the high prices.

Sebastian

Dr Hamilton – are delinquencies the proper metric to measure the ‘anti-bubble’? And also if a bubble appreciates at price appreciation rate X, does it necessarily have to go down at a similar rate? How do economists measure or account for ‘stickiness’?

BTW – many of us accused of being ‘bubbleheads’ didn’t like the term ‘bubble’ either… but there was clearly something fishy going on as RE prices quickly outstripped ‘normal’ peoples ability to afford ‘normal’ homes.

Thanks for a well thought out & presented case.

house price appreciation has very little (not nothing at all, but very little) to do with delinquency. Delinquency is driven by cash flow problems, such as unemployment (and ARM resets). The probability of a foreclosure, given default, is what’s driven by house price appreciation (if you have a cash flow problem and houses have appreciated, you sell, if not, you get foreclosed on). And that process a) takes time because months pass between delinquency and foreclosure and b) for someone who bought their house 1 year ago, it’s appreciation over the last year that matters, for someone who bought 5 years ago, it’s appreication over the last 5 that matters. I wouldn’t expect much relation at all between delinquency and appreciation, and I wouldn’t expect a relationship between foreclosure and delinquency to be a leading, or even coinceident, indicator.

Wouldn’t a much better measure of the bubble or not bubble be the correlation between house price changes over the last quarter or so and house price changes over the previous 5 years? If high appreciation in the past was a bubble, and expectations have changed, then those are the areas that will show high depreciation now. I haven’t tried it, and you are welcome to, but I have looked at the OFHEO MSA data, and except for Detroit and a couple of nearby areas heavily into autos, I suspect you’ll find exactly the correlation that would indicate a bubble.

er – make that relationship between foreclosure and house price appreciation, not foreclosure and delinquency. more than two variables can make my brain hurt.

RE: S. Staniford’s comment about CA. We are currently seeing a shift in the measures for CA and it seems to be rather interesting, indeed. Is this the second wave?

CA – Updated: 03/23/07 6:13 PM

Foreclosures: 18,339

Preforeclosures: 62,646

Bankruptcies: 25,805

FSBOs: 1,185

Tax Liens: 259,541

(Source foreclosures.com…yes I too have some issues with the tabulation but ya work with what ya got on a timely basis and the point is I have never seen CA at this level. Kinda looks like Detroit numbers in November/December 06. A blip beyond measure)

“I think it is quite reasonable to use Gold as an unbiased proxy for the general price level. Using it that way obviously paints a far different picture than simply looking at nominal housing prices.”

At the end of the day people will have to pay their loans with money, dollars, not gold. Salaries are paid in dollars not in gold (at least for the most cases that I know)

Wages and salaries have been increasing at about 2.5% to 3.2% annual rate for the past five years (see ECI index). Prices can rise faster for a period of time as long as extra money flows into the sector. If the support doesn’t come from salaries then it probably comes from extra credit. If you compare the price increases with wage increases, they look somewhat different. But if you consider that and add the increase in mortgages (see flow of funds), compare them compound with the increase in median house prices, it begins to make some sense. And loans must (or at least should) be paid back so there is a limit how much credit can increase demand and prices on an asset that doesn’t really produce anything..

“Why would states that had the smallest real estate price gains be the ones that are now having the biggest problems?”

Seems pretty simple to me. If I’m in a high appreciation area, I can sell my house for more than I paid, and that keeps me out of trouble.

In very few words. Could the people of say California or the city of Phoenix afford to buy houses at the current income to house price ratio using a conventional fixed rate or variable rate?

I see job growth as important but are salaries growing to to accomodate the increased home prices. I think not.

So how do you explain a 6x-10x income to mortgage rate? How would you maintain that as a norm? 3% interest 30yr fixed loans? Traditionally for fiscally prudent individuals the ratio is closer to 1.3-2 and 2-3 if you’re pushing a little harder.

“The price of a house isn’t just what the seller says it is, it’s the price the seller and the buyer agree to.”

Sebastian… consider this:

The price of a [tulip] isn’t just what the seller says it is, it’s the price the seller and the buyer agree to.

Just ’cause sellers sell & buyers buy doesn’t mean there is or isn’t a bubble.

Sebastian asks: “What DID cause the huge price rise, if no one could afford those houses and no one was paying those prices? The price of a house isn’t just what the seller says it is, it’s the price the seller and the buyer agree to.”

Are you not aware that all manias start this way?–Initially, a very small percentage of buyers, flush with cash–either because they earned it or because they were able to get easy credit, are willing to engage in a bidding war and that causes the prices to go up a bit more than what was seen previously. So in that sense what you say just the initial catalyst. But you are missing the point?what is interesting is what happens after that.

As stories about easy riches (and fears of being priced out forever) spread, and more and more people get into the action, often stretching themselves beyond what they could afford, with creative financing, etc.. This process spreads the mania and sustains higher prices over a period of time. Manias don’t and cannot reverse quickly. The full after effects of lending to people who couldn’t afford loans?(and creative financing) haven’t yet started. The truth is the bursting of the bubble has just started.

The professor is WRONG on a number of counts.

Bubble theorists did NOT say expectations of price rise is the ‘ONLY’ thing propping up the market. But it certainly contributed more to move the prices sky high. And given that this irrational belief in ‘fundamentals’ prevails among Sebastians, University professors and Fed Reserve bankers, it is obvious that the psychology that generated the bubble hasn’t reversed yet significantly–yes appreciation has stopped, but too many people I know still think that after a brief pause, prices will rise again. That belief has certainly propped it up. So the culprits propping up the bubble include the irrational minds of professors and bankers and bloggers as well.

The professor’s second argument is again WRONG, because prices did go up much more than what one would have expected based on historical appreciation locally even in the areas where the rise was relatively tepid. Prices went up significantly more than the norm in such places as West Virginia, Missouri, Kansas, Texas–hardly places of significant job and population growth.

That the initial catalyst for the mania is stronger in areas where job growth and population growth are strong, and therefore the resulting mania will be stronger in such areas is self-evident. The same explains why delinquencies and foreclosures are high in less bubbly areas, but it is just the beginning of the bursting. The professor doesn’t understand the meaning of ‘psychology’ and doesn’t know how to handle this in his forecasting models. That is why he keeps repeating these stale, discredited arguments, much like a believer in God repeats arguments discredited hundreds of years ago..

As for population growth, it doesn’t rise so sharply within one year to cause 40% appreciation in prices per year. To think population increase caused the bubble prices between 2003 and 2005 is so irrational that I am sorry to question the professor?s credibility as a scholar.

What he could have said is that there is always hidden demand due to population growth–what is normally missing is affordability and availability of credit, and when creative financing and fraud cater to that hidden demand from growing population, that add to rising prices.

.

My logical conclusion: Prices will fall for much longer as more people like Hamilton and Sebastian slowly learn the market’s reality, and by year 2015, I am convinced that the prices in many areas will be at a level seen in 2004–2006, in nominal terms. In ‘real’ terms, the prices seen in 2005–2006 will not come back for some decades until another mania starts and people with short memories poor understanding of psychology forget the history if this current bubble.

Wow, what a long, strange thread.

JDH, nice post.

That said, the rational thesis isn’t “bubble” (housing isn’t the type of traded good that conforms to that model). Barry Ritholtz and others have suggested “souffle” which suits my recollection of the last two slow in-/deflations of residential property values.

Mr. Davis, I like your paper. I am not sure I quite buy it yet, but then I am less focused on land value and more on unit housing costs. Whether or not your conclusion holds, the datagathering exercise alone is fine work. Kudos.

Speaking of data, I find the harbingers of a souffle start to appear in the data quite late, but unmistakably. Shorting homebuilder stocks (which trade for the moment I have exited, but may want to reenter on rallies) has been quite wonderful since just after the homeowner vacancy rate spiked in mid-2005.

Sometimes when refuting the straw man (“it’s a bubble”) you miss the truth. Here, prices went high enough and rates low enough and incomes held up enough to create a classic oversupply. That souffle needs slowly to deflate, as I expect to happen over the next half-decade.

There is no “bubble”, but that was never the issue. There are too many units now, and too few people to fill them. As a result, I wouldn’t bet on any more 5+%-real-price-appreciation decades the way we saw from 1997-2006. Not soon, anyhow.

People in the middle- or lower-income strata may be priced out of housing, but there are clearly other people that aren’t and they’re the ones that can “support” the high prices.

True, high prices in my neighborhood are being supported by the few who can afford to buy here. But California’s problem is that vast numbers of new houses have been built within a 250 mile radius of high-income population centers, probably with the hope that if you build it, the affluent will come. Sorry, there just isn’t enough income and wealth to soak up all that housing, but if that’s not a bubble to you, so be it.

Professor Hamilton,

My compliments on an excellent post – and I would be very grateful if you and your commentors could help a confirmed non-economist with a couple of questions.

1. Obviously the very definition of a bubble is contentious. Should the pace of asset value growth, just by itself, carry greater weight in the definition than it seems to?

To use my own experience in the British housing market as an example, we bought our apartment for 77,500 in 2005 (five years fixed rate – Deo Gratias). The seller had bought it for 49,500 in 2000. It’s not Buckingham Palace but it’s not a hovel either, and the neighbourhood is relatively pleasant but not particularly fashionable.

Assuming it to be relatively average, should a growth increase of over 50% in five years by itself constitute evidence of a bubble? Particularly when reported inflation has been low?

2. It’s noticeable that the states which have the highest failure rates are Louisiana and Alabama. Without wishing to move the thread into either the climate change or FEMA minefields, could there be any connection between this and these states’ failure to recover from Katrina?

And if that might be the case, what could possibly be done to reverse that rot now without implementing ‘New Deal’ style works programs? Or is the New Deal just what might be needed to kickstart a recovery, because those very dark blue bits on the map don’t look healthy.

3. The most startling aspect of Calculated Risk’s delinquency map is that, with one exception, a state with a delinquency rate of at least 4.96% is very likely to border another. Not being either a housing or labour economist, it’s hard to see how the two cannot be connected – graphically, it’ just too neat.

Any thoughts?

From a post by a suburban Chicago realtor:

“… 27 sellers reduced their asking price this week. There were 51 new listings … and 20 sales contracts were written. …”

Figures from that post for March 21:

Avg Days

Listings Avg price on Market

3 bedroom houses:

178 $410,675

135

4+ bedroom houses:

221 $701,798

168

Condo’s/Townhomes:

322 $249,832

149

(See original post for eight more weekly samples dating back to September 2006.)

But the Chicago Sun-Times listings for actual sales in this suburb in 2006 show us that only 51 homes sold for $700k or more (the avg. 4-bedroom asking price above), while the MLS shows 98 4-bedroom homes at $700k+ asking (and 94 at $735k+ — let’s allow for the pre-bubble custom of actual sale price 5% below asking).

Since we are often told that a lot of the homes on the MLS are just being listed by people who don’t need to sell, and are just thinking that if someone wants to meet their wishing price they’ll sell and move up to something nicer, what’s most interesting is the fraction of those $700k+ homes that stand vacant: 70%. Yes, seventy percent. I just spent two hours clicking up every damned one of them on the MLS and checking the photos. Another 5% are clearly occupied by people not in the income bracket you normally associate with million-dollar homes (house-sitters?). So not only is there two years’ worth of inventory on this market, there’s more than a year’s worth of vacant inventory. Almost all of this is newly constructed spec homes built on lots cleared by teardowns in a mature community of about 50k population. Sure looks like a speculative bubble to me.

Alas, preview does not show what the actual formatting will be — I took great pains to make the above look right in preview mode.

The figures are, in order, the number of listings, the average asking price, and the average days on market.

Arlington Heights home sales, 2006

Arlington Heights home sales, 2005

What Conundrum?

Mohamed A. El-Erian of the Harvard Business School and Noble laureate in economics Michael Spence say there’s nothing puzzling or hard to understand about global imbalances, declining risk spreads, flattened yield curves, and declining market volatilit…

Professor i think you need to redefine your terms.

The bubble creates a *peak* price that could not be obtained without bubble mania, but this is not to say that many aspects of the price were not sensible components to the price.

Prof. Hamilton asks why, if bubbles are based on expectations, would expectations have suddenly shifted only in some areas. Um, aren’t those areas almost entirely areas with inelastic housing supply? If there’s a nationwide increase in demand (looser lending standards) won’t that show up as higher quantity in Charlotte and Columbus (surrounded by farmers willing to sell to developers) and higher price in Los Angeles, Miami, and Las Vegas (surrounded by oceans and mountains, ocean and the Everglades, and BLM land that the govt. dribbles out in small lots, respectively)? Wouldn’t a plausible trigger for “expectations of rising prices” be “prices are actually rising?” I don’t think it’s a surprise that expectations of ever rising prices broke out only in places where housing (land, especially) is inelastically supplied.

I tripped in the first paragraph:

“So, if expected price appreciation was the only thing propping up the market, we should now be seeing a calamitous price collapse rather than the slow fizzle that’s unfolding.”

I think that implies a more liquid market than we have in residential real estate.

… I don’t know, this morning it seems to me that society went debt-crazy and that home defaults are just one part of it. Does that make a “bubble?” What are auto loans doing?

Oops …

“Among other things, auto finance organizations are facing a rising tide of subprime auto loan defaults, escalating application fraud and issues concerning customer retention, while mortgage lenders are seeking to reduce their losses caused by the rising tide of non-prime loan defaults, the fall in housing prices, and the rise in mortgage fraud, among other things.”

http://press-releases.techwhack.com/8112/impact-2007/

Tedk, I offer in support of my conclusions maps, graphs, R-squareds, and t-statistics, and you offer in support of yours anecdotes and invective. And you conclude that one of us is holding to our preconceived notions as if to a religious conviction.

The price appreciation was primarily driven by low interest rates, not by population growth. What population and the availability of housing matter for is for why different communities responded differently to those low interest rates.

Kharris, Stuart, Martin, Donna, and others– The semantic distinction I’m really trying to draw here in the definition of a bubble is between two classes of mathematical models. In one, there is a unique mapping from economic fundamentals into an equilibrium price of housing. Those fundamentals would certainly include interest rates, credit requirements, population, incomes, and supply of housing, among others. In the second class, there is not a unique mapping, but a given set of values for the fundamentals could be associated with an infinite set of possible price outcomes, depending on an “expectations” variable that comes out of the blue and is not pinned down by economic theory.

Of course expectations do matter a great deal in anybody’s model of the housing market. But in an economic fundamentals framework, they are themselves the endogenous outcome of the particular fundamentals, rather than a separate exogenous variable you can add as a free variable to the system.

I realize that this is slightly treacherous ground here, since the word “bubble” has been appropriated by the popular public as a term they all feel free to use. But the problem is that no two people are using the term “bubble” in exactly the same way. Indeed, many of the commenters above seem to be describing what they call a “bubble” in terms of a framework that I would instead describe as an “economic fundamentals” way of thinking about things

For what it’s worth, what I heard most often from first-time buyers here in Orange County, California, was fear. Fear that if they did not leverage with those loans to get into the market, it would leave them behind and they’d never have the chance at home ownership. That sounds bubble-like to me, but I take a somewhat fuzzy approach to … most everything.

Is adaptive expectations an economic theory, by the Prof.’s definition? If adaptive expectations generate wild, predictable price gyrations (and I think they can), can we not call this result a bubble, because the expectations variable is endogenous?

If we can call the result a bubble, then doesn’t our current situation pretty much follow perfectly? In the flat lands, easy credit generates an increase in demand that doesn’t ramp up price, price expectations stay flat, and no bubble forms (but if the easy credit reverses itself, prices will drop, as housing is pretty much a putty-clay model). On the coasts, easy credit generates an increase in demand that does ramp up price, people cocnlude that since prices rose a lot last year they’ll continue to rise a lot, ramping up demand, hence price, even further, until a limit gets hit where the process hits a wall, prices flatten, the expectation disappears, and prices tank. Sure sounds to me like the San Diego or Miami Beach condo markets.

The Prof. asks why price expectations would only break out in certain areas? Then goes on to assert that a fundamental driver of price appreciation was low interest rates. I might ask why low interest rates would only generate high prices in certain areas?

mort_fin, I would include adaptive expectations models (in which the expected price appreciation is a function of past price appreciation) as an economic fundamentals model, since, when you solve it out, the price is a function of the current and past fundamentals. A rational-expectations and adaptive-expectations model could behave similarly or could behave quite differently, depending on the parameters. However, when they behave very differently, one then gets into the further question of how the lenders of mortgages could base their expectations on something so far removed from what happens. And then I think you are getting back to the issue of possible market failure, which is where I’m trying to steer the policy discussion.

mort_fin, on how interest rates interact with local growth rates, see my discussion here.

If wild price gyrations (beyond those that can be explained by changes in discounted expected future streams of benefits) are not bubbles, by definition, if they result from adaptive expectations, then we’ll have to agree to semantically disagree.

On lender behavior (a better term would be ‘bearer of credit risk behavior) I agree that it’s the most fascinating question. I don’t have an answer beyond a vague principal-agent issue. Everyone assumes that everyone else is minding the store. The investors trust the rating agencies, the rating agencies trust the lender’s modelers, the lender’s modeler’s trust the investors.

Let me back this vague assertion with an anecdote (at least it’s a true one). A friend had gotten his PhD. from a top 20 econ dept. and was taking a job as an assistant prof. at a top 20 econ dept. Just before flying out to find a place to live, he asked me about search strategies for housing, as he figured I knew something on the subject. I gave him what I thought was lots of good advice. When he came back he had found a place. I asked him about my advice, and he told me that a search strategy would have been far too expensive. Instead, he talked to an asst. prof. with a similar demographic who had moved there in the previous year, and moved to the same place that the other guy had moved. Why search when I can free ride on someone else’s information? That works well for awhile.

I think the main problem that with assuming that everything fits the rational model is that information isn’t free. Data comes with lags, models aren’t proprietary, and the principles and the agents don’t always have incentives that align. Relying on last year’s decision process is cheap, and works most of the time.

I think it’s also interesting to note that the players with the best private data have not been driving the lending boom. The GSE’s have reduced their market share, the PMI’s have reduced their market share. The growth in lending has come from subprime lenders who sell their packages through Wall St. to hedge funds and overseas investors, and the first loss position is being born less and less by PMI’s and more and more by holders of second liens.

When the entities that have the data are backing off, and the entities that don’t are expanding, I’d be a little reluctant to endorse the ‘everyone’s rational’ point of view.

Thanks, Professor.

Jim,

Going all the way back to your first point. Calamitous price collapse after a peak does not necessarily happen after the peak of a bubble. I suggest people look at Appendix B to one of the later editions of Kindleberger’s Manias, Panics, and Crashes. He lays out the time detaiils of 46 of history’s most famous bubbles, although Jim and Peter Garber might argue some of them were not bubbles. Only in a few did prices drop sharply right after the peak. Some declined very gradually, with no crash ever. That is what happened to Japanese real estate after its peak in 1991, only turning around finally in 2005.

The majority of the bubbles in Kindleberger, including most of the biggest and most famous, experienced a “period of financial distress” for some period after the peak, anywhere from a month or two to over a year. That is a period of gradually declining prices that precedes a crash that finally does happen. I have a freshly updated paper on this topic on my website at

http://cob.jmu.edu/rosserjb, entitled “The Period of Financial Distress in Speculative Markets: Interacting Heterogeneous Agents and Financial Constraints,” coauthored with Mauro Gallegati and Antonio Palestrini.

Also, Kindleberger makes it clear that most (apparent) bubbles at least begin with some “displacement of a fundamental.” So, just noting that interest rates went down and employment went up (although not as fast as in teh 1990s), along with land-use supply constraints is not enough to disprove that there was a bubble. Of course, Jim, you are along with Garber the “misspecified fundamental” guy who has argued that one cannot disprove that a particular price series does not reflect some rational expectation of the future path of fundamentals (even as Shiller showed the highest price to income and price to rent ratios for housing recently ever seen in US history).

Of course in the earlier thread on subprime mortgages, you never did comment on my point about closed end funds… (For others I note that I have a paper on bubbles in closed end country funds around 1989-09, “Complex bubble persistence in closed-end country funds,” with Ehsan Ahmed, Roger Koppl, and Mark White, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Jan. 1997, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 19-37, that was before I became editor of JEBO, just for the record.)

Oh yes, a further extension of the misspecified fundamental argument is to argue that there really is no fundamental, or not one that can be identified. Besides ratex econometric arguments like Jim’s and Garber’s (see his fascinating, _Famous First Bubbles_), the Post Keynesian Paul Davidson has argued this on Keynesian uncertainty grounds, and some econophysicists have also argued it, most prominently Jean-Philippe Bouchaud, who edits the journal, Quantitative Finance, when he is not teaching physics and managing a highly successful hedge fund in Paris.

JDH: “I offer in support of my conclusions maps, graphs, R-squareds, and t-statistics, and you offer in support of yours anecdotes and invective. And you conclude that one of us is holding to our preconceived notions as if to a religious conviction.”

Professor, I am sorry about using strong words like ‘genuine economist’, ‘credibility as a scholar’ etc.

Anecdotal experiences are relevant when we know economics is only an imperfect and dismal social science and not a science. I did my PhD in Electrical Engineering from a top 15 engineering school, and am not easily impressed by simple math, charts and graphs from economists.

Before I explain some reasons for the ?religious conviction? issue, let us take your other comment. “The price appreciation was primarily driven by low interest rates…”

The numbers in your original post in 2005 assume an interest rate on 30-yr mortgage changed from 8.5% in 2000 to 5.75% in 2005. However, the bulk of the price appreciation was between 2003 and 2006, during which interest change was only from about 6.5% to 5.8%. In other words, can your simple math using interest rates explain a 70?80% price appreciation between 2003?2006 ? Your assumption of a 50% rise between 2000?2005 is not valid for the coastal areas?it was much higher.

Another mistake is in taking the time period for your calculation as 2000?2005 since the bubble era post-2003 is smoothed over by relatively smaller appreciation during 2000?2003.

.

And can you show that the extra population during that period that pushed up the demand (it is your claim) because of lower interest rates, could finance their homes using 30 year fixed mortgage, as opposed to creative financing?interest only, ARM, etc., and downright fraud?

Now let me explain why I make reference to believers in God. Those who are easily taken in by misleading arguments and deny the bubble have the same thought processes as believers in God. Despite evidence to the contrary and despite centuries of rational thought, a majority of the world?s population continues to believe in some form of God. Why? Because a critical part of the brain which is responsible for reality-checking and innate skepticism is deficient in believers

The same is what leads people to ignore evidence of bubble everywhere and continue to believe that it was market fundamentals that caused the prices to skyrocket. That is not to say that the latter set of people are all believers in God, but they have the same deficiency of thought and make the same mistakes.

Despite believers being in a majority, non-believers have truth as well as accomplished people on their side. The same is true of Bubble theorists?though in the minority, they have facts and the likes of Shiller, Krugman, Roubini, Warren Buffett, George Soros, Gary Shilling, Jim Rogers, et al on their side.

I am reminded that Medical doctors are best advised not to say anything critical of coca cola because (I am told by a doctor) that coca cola sponsor medical research.

Seems news channels have similar restrictions about Monsanto products.

Obviously if academia calls a bubble it would not be good for the economy. Obviously it is in the interests of the economy that the bubble deflates very very slowly or simply remains inflated until wages rise to fundamentally support it.

California itself seems to have areas of horrific public financing relying on assett prices remaining strong?

Bubble? I see no bubble!

We have both assumed, to some extent, that lenders are crazy to be lending in bubble areas. The Prof conditionally (IF there is a bubble, then musn’t lenders be a little nuts) and me rather less so (there is a bubble, so lenders must be nuts). I fell into a vague answer because I suspect that lenders have been a little nuts. But there is a more rationally satisfying answer.

Lenders don’t have to be nuts for there to be a bubble. If a bubble is happening, but you can’t forecast how long it will run or how high it will go, then lending in a bubble area involves a heightened risk, but not a certainty of loss. With heightened risk, all you need is the ability to charge enough extra to cover it. It is certainly possible to have a bubble, have the lenders know it is a bubble, and have lending in support of the bubble happen anyway, so long as a) home buyers are irrationally optomistic enough to pay the risk premium for the loan on top of the high price for the property and b) the length and magnitude of the bubble are stochastic.

While I think both lenders and borrowers have been nuts, you only one to be nuts to get gyrations beyond the fundamentals.

From an AP story:

“Many families, though, likely never would have become owners if not for the tremendous growth over the past decade of a new kind of mortgage business called subprime lending. It long seemed like a winning proposition for all parties. Now the costs are becoming apparent _ and they are very unsettling.”

Professor, you may choose to play with words and switch terms around- call this housing mess what you so choose. But in the real world there is a housing bubble brought about by a reckless credit bubble which is just in the beginning of playing itself out.

TedK said: “Anecdotal experiences are relevant when we know economics is only an imperfect and dismal social science and not a science. I did my PhD in Electrical Engineering from a top 15 engineering school, and am not easily impressed by simple math, charts and graphs from economists”

Economics is a construct of academia. It is not science. Thus explains the crazy ideas on this blog.

Nor am I impressed by simple math, charts and graphs from economists, Tedk. I called your attention to these again in my comments to you above not in the hopes that you would be impressed by a t-statistic, but rather because I thought that you might recognize these as objectively grounded in statements of fact. And on that dimension– whether one is making an objective statement of fact or simply asserting a strongly held ideological opinion– I at least was quite struck by the contrast between the character of my original remarks and your response. Hence my amusement at the vehemence of your insistence that anyone who holds a different conclusion from you must simply be blinded by their faith in their prior beliefs.

I think all PhD Electrical Engineers should just get it over with and give themselves Nobel Prizes in Everything. Why do they torture everybody else with this…insecurity?

Of course James is right that a housing “bubble” is not like the one in your bathtub that perishes suddenly, and of course he has this knowledge of previous housing booms (also called “bubbles”?) and knows this unwinding takes years, not days or months.

And so the catastrophe (downside) time frame has this elongation rather than that dramatic “Pop!” that some (greatly exaggerated, I think) apparently were expecting taking the bath water too seriously.

But that balances out the media’s “soft vs hard landing”, somewhat, yes? who do not use the terms “attenuated vs extended correction”. In fact it may just be the media’s failure to use the histrionic language on this occasion (that viewers are so accustomed to) that cultivated this public inclination to talk this ‘boom’ into a more exciting and precarious “bubble”.

I believe I will borrow a term from Herbert Stein.

Banana.

We are now experiencing a residential real estate banana. (Ben Stein…are you reading this thread?)

This banana will play out zip code by zip code…what happens in Oakland County, MI will have just about as much in common with what happens in Oakland, CA as an amoeba has with an ant.

“Why would lenders continue to loan in bubble areas”?

The manifestation and rapid evolution of the securitized mortgage market over the past five years has contributed to a blind faith in credit risk management. The mortgage broker does not care about the risk as he is paid a fee and often enables the soft crime of mortgage application fruad (stated income loans, etc.).

The correspondent lender does not care about the loan as they too are paid for thier bulk loans passed on to hungry securitizers. Volume is the key to thier business.

The large securitizers believe that the risks have been vetted and can be statistically controlled by mixing them in large batches with other prime loans, the resulting concoction sold off as tranches with buy back “guarantees” and financial hedges. These CDOs appear to have little risk (risk compression has been coincident with the rise of CDOs over the past five years). The preceived lower risk translates to a lower interest rate which is of course passed back to the beginning of the loop.

JDH’s analysis often reminds me of Morgan Mafia, the originators of derivatives/CDOS/CLOS/CDS etc or perhaps of GAVECAL’s polyannas.

Do an analysis, include lots of fancy regression, probabalistic, faux risk analysis (all new age math so to speak) and come up reinforcing preconceived notion by unconscionably excluding some vital factors in their equations..

Such an analysis pretends to be predictive and reassuring to the laity, but the market forces at the end betrays its faulty reasoning….

Here in sunny south florida, inventory is at 3 yrs…median home prices at ~8X median. Buyers since 2005 are yet to be convinced that their purchases were borne out of fundamentals..Even though, the respectable professor had told so..

i also wonder if timing of this post had anything to do with the global markets’ 78% FIB retracement since FEB 22 debacle..

If at all this tells us the extraordinary liquidity that still exists in the system even as some measure of credit crunch is seen in mortgage business..

However persistent inflation and significant unemployment by year end remains a very serious threat..

One of the problems with standard economics training is that the econometrics focuses on linear regression and tends to skip over non-linear functions. Most economists would never consider a curve may be, say, a Poisson distribution. Many sem to think adding a squared or cubed term to their model is the height of sophistication!

Lets look at just a few things that are up in price more than real estate the past six years:

Corn

Wheat

Oil

Gold

Euro Currency

http://investmenttools.com/images/re/re_median.gif

During the tech bubble, tech stocks outperformed everything else decisively. So did tulips during the tulip mania in Holland. In the past six year real estate prices in the US have underperformed some basic goods like oil and corn.

“In the past six year real estate prices in the US have underperformed some basic goods like oil and corn.”

Houses are not a commodity like gold, oil, wheat and corn.

Actually real estate and commodities share a key attribute the world over. People use them as a hedge against currency depreciation. The reason it is useful to look at other prices is to see whether what happened to real estate was unique. Obviously it wasn’t. It seems like a host of prices went up since 2001 and many of them more than housing prices.

And interesting that you left out the Euro currency, since from the point of view of Europeans real estate prices in the US didn’t even appreciate. So this could have been more about the dollar than about housing.

Morris Davis above touches on an important point: the decomposition of house prices into structures and land. In many cases, those municipalities that have the most unaffordable house prices (in terms of income multiples) are also subject to some form of government-mandated supply restrictions, while those with more affordable markets have fewer restrictions. Good old-fashioned supply/demand dynamics still appear to work in determining house prices, it seems.

Anyone who loves to ponder on housing affordability and housing bubbles is welcome to take my quiz on ten international markets.

Bubble, bubble, toil and trouble…

Thank goodness that Prof Hamilton didn’t start a thread on how many angels can fit on the head of a pin.

mort_fin,

Actually, if the borrowers and lenders all know there is a bubble and are building the probability of it crashing into their pricing with appropriate risk premia, then they are not nuts. This is in fact the model of the rational, stochastically crashing bubble presented in 1982 by Olivier Blanchard and Mark Watson. Of course, we have seen little evidence of any risk premia in recent financing of the US housing market, clearly part of the problem.

calmo,

It was me, not JDH, who raised the possibility of bubbles dying slowly. His opening remarks imply that a price series is really a bubble only if it crashes right after it peaks. This is indeed compatible with the conventional theory, based on representative agents models with rational expectations. The price rises only on the self-fulfilling expectation that price will rise, and when it stops, “nothing is holding it up,” so therefore it must crash instantly.

This view is contradicted by the more realistic one that agents are heterogeneous in expectations and wealth and cannot be represented by a representative agent. Their heterogeneity matters, and shows up in the historical fact that most bubbles have declined slowly after their peak, with most eventually crashing, but some just continuing to decline slowly, as for example Japanese real estate.

However, real estate can crash suddenly, e.g. the Florida land bubble of 1925.

Frothy cyclical highs are often mistaken for bubbles. Frothy highs are common. Bubbles are not.

Bubbles burst and collapse. Cyclical highs decline over time. No collapse no bubble.

Sudden external factors can cause a sudden collapse when there was no bubble. They can also cushion a bubble to prevent the sudden collapse. However, barring a (perfectly timed) sudden and significant new force there will be a sudden collapse if there is a bubble. Dont hold your breath for this one.

Prof. Hamilton,

I think your bubble analysis is spot on.

As a decades-long real estate investor I find your disciplined analysis to be consistent with my own casual observation. I remember what it was like during the ups and downs of four full cycles since the 1960s. In addition to my casual observations, I began studying the real estate cycle during the 1970s using data for the preceding 50 years. I update my data and analysis regularly. History supports your assertions.

What we are experiencing is a typical asset price cycle that is driven by measurable forces that are predictable. Fundamental forces such as demography, incomes, interest rates, employment, supply costs and others rule the day in the long run. In the short run the market is also significantly affected by expectations that range from pessimism to exuberance. These are also predictable.

So far this cycle has played out in magnitude and timing just as I expected before the run up in prices started. Accordingly, I bought as much real estate as I could from 1998 through 2003, and sat tight until 2006 when I sold some property. Now I am waiting for the bottom, which I expect will come no later than 2009.

There is/was no bubble by correct use of the term. But there have been frothy bubble-like characteristics present in the market. There are frothy elements in every cyclical high. I think people misuse the term bubble to describe a frothy market that has merely exceeded its fundamental supports (as all markets do). This is not really a bubble in the true sense – merely a cyclical high. But most people miss that distinction, and perhaps it is not important.

I greatly appreciate the high quality of your blog. I hope you will avoid the trap of trying to teach Econ 101 here.

Zephyr,

I suggest you go read Kindleberger and his accounts of the great historical bubbles. Among those that did not immediately collapse after their highs were reached include the French Mississippi Bubble of 1719-20, the British South Sea Bubble of 1720 (both of these had roughly four months of gradual declines before they collapsed), the 1929 US stock market bubble (peaked at beginning of September, crashed on October 24), and the 1987 stock market bubble (peaked in mid-August, crashed on October 19).

For that matter, regarding the ones that decline slowly, would you seriously argue that the sharp runup in real estate prices in Japan in the 1980s was not a bubble? It rose simultaneously with the stock market. The stock market did crash suddenly in early 1990. Real estate peaked in 1991 and then came down more slowly than it rose, not bottoming out until 2005. Was the stock market a bubble and real estate not? If you make such a claim, then I think you are much too taken in by simplistic theoretical models.

BTW, for what it is worth, I can tell you that from personal communication with him, I know that the late Professor Kindleberger most definitely viewed the two bubbles in Japan as both bubbles and deeply linked with each other, although he was somewhat mystified at the peculiar behavior of the real estate one. Its behavior remains even today something not well understood or explained.

Four months of lull before a collapse is not a gradual decline. It is a brief wobble at the top preceding the collapse. All of your examples are collapses not gradual declines.

Four months of slippage is nothing. The collapse is the story.

As for bubble markets in Japan, a collapse can be followed by a prolonged decline. The fact that the continuing decline lasted a long time does not negate the collapse phase.

Sorry Barkley for assuming James was using the term “bubble” as per his definition:

First, let me define terms. I think of a price bubble as a market outcome in which the price rises for no reason other than the fact that everybody expects prices to keep going up. The first problem with that as an interpretation of the recent behavior of U.S. real estate prices is that surely it is clear to everyone by now that real estate prices have stopped going up. So, if expected price appreciation was the only thing propping up the market, we should now be seeing a calamitous price collapse rather than the slow fizzle that’s unfolding.

which nails down for him what this publicly used term “bubble” means –no matter it being a publicly used term that does not recognize James, Barkley, calmo, or any other august authorities. [We public users of the term are not about to shift our meaning and sense of the term to align with James’s technical specification.]

But I think this tech spec of “bubble” is close enough to the bathtub variety, (but I demand you ignore this as authoritative).

We care about what ordinary people mean when they use the term: it’s the bathtub variety…and they mean to convey roughly (this B it: no precise specifications about what the hell they really do mean) that it’s a rather sudden ending.

All you physicists out there that are about to launch your missiles on The Surface Tensions of Soap Bubbles can take a hike.

Zephyr,

Well, first of all there was no crash for Japanese real estate, not right after the peak and not later. Went up very fast and came down very slowly and gradually for a good 14 years after.