Jim Hamilton’s recent post “Bubble, bubble, toil, and trouble” elicited a tremendous amount of commentary — and incredulity — amongst the readers.

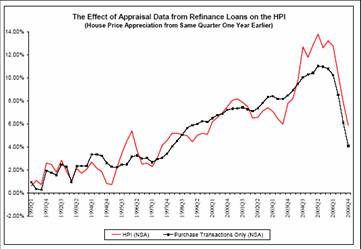

Figure 1: Annual growth rate in OFHEO Housing Price Index and in index of transactions prices. Source: OFHEO March 1st release.

One example of a skeptical view is provided by Aaron Krowne:

Some People Are Still Denying The Bubble

by Aaron Krowne

Sunday, March 25, 2007

“… I was just skimming some blogs I’ve missed, and found this surprising post from Econbrowser writer James Hamilton, attempting a dismissal of the “housing bubble” thesis (yes, you read that right), which I had to draw attention to. The analysis is rather weak — a conflation of early-stage delinquencies with price appreciation and declines — but that doesn’t stop Hamilton from resorting to it.”

I believe some of the excited commentary arises from the differences in how economists use the word “bubble” as opposed to how the general public uses the word. This is true despite the fact that Jim has laid out the logic quite clearly in one of his early posts on the topic, “What is a bubble”, from June 2005:

“All of which is a rather long diversion before getting to answer the promised question: what exactly is a bubble? Economists would say there’s a bubble in the market if home buyers are basing their expectation about the price that they can sell the house for in the future on something other than the affordability and desirability of that home to the future buyer. In a bubble, borrowers are assuming they’ll have a capital gain on their house big enough to bail them out of the deep debt they’re getting into, even though it would mean an even bigger debt burden for the next folks down the road. But one of those future buyers, if we looked ahead rationally, is going to be forced to say, no sale.”

Jim lays this argument out formally as follows. Let:

Ht = st/(1+it) + Ht+1/(1+it)

Where H is the price of a unit of housing, s is the housing services provided per period, i is the interest rate. Then by recursive substitution, one obtains (with a slight modification of Jim’s equation):

Ht = st/(1+it) + st+1/[(1+it)(1+it+1)] + st+2/[(1+it)(1+it+1)(1+it+2)] + Ht+inf/[(1+it)(1+it+1)(1+it+2)…(1+it+inf)]

…

Where “inf” is infinity. In other words, the price of a unit of housing is equal to the present discounted value of housing services provided over time.

Pursuing this further, one finds the general solution to this is:

Ht = f[(st+j)/(1+i)t+j] +

g[Ht+T/(1+i)T]

For it+j = i for all j, and f[.] denotes the sum from j=0 to infinity of [.], and g[..] denotes the limit as T goes to infinity of [..].

Typically, economists set g[..] to zero, although mathematically, there is no particular reason to do so. The g[..] object is the “bubble” term, insofar as it represents the possibility of price appreciation in excess of what occurs via discounting.

This expression can be made stochastic by re-expressing the future housing services and interest rates in expected value terms. A “rational stochastic bubble” is then defined as one where the price reflects some expected appreciation not linked to fundamentals. Unfortunately, testing for rational stochastic bubbles is not easy. That is because the time series process for expected fundamentals is not knowable, and indeed the presence of rational stochastic bubbles cannot be distinguished “process switching” (i.e., changes in the underlying process for the fundamentals, as discussed by Flood and Hodrick).

Let me say that while I allow that there might have been a rational stochastic bubble in the housing market, I think that the gradual revelation of improper lending practices and excess risk taking in an environment of inadequate regulation suggests to me another interpretation, laid out in a paper by George Akerlof and Paul Romer in the Brookings Papers in Economic Activity 1993(2), in the context of the Savings and Loans financial crisis of the 1980’s:

“Our theoretical analysis shows that an economic underground can come to life if firms have an incentive to go broke for profit at society’s expense (to loot) instead of to go for brok (to gamble on success). Bankruptcy for profit will occur if poor accounting, lax regulation, or low penalties for abuse give owners an incetive to pay themselves more than their firms are worth and then default on their debt obligations.

Bankruptcy for profit occurs most commonly when a government guarantees a firm’s debt obligations. The most obvious such guarantee is deposit insurance, but governments also implictily or explicitly guarantee the policies of insurance companies, the pension obligations of private firms, virtually all the obligations of large or influential firms. These arrangements can create a web of companies that operate under soft budget constraints. To enforce discipline and to limit opportunism by shareholders, governments make continued access to the guarantees contingent on meeting specific targets for an accounting measure of net worth. However, because net worth is typically a small fraction of total assets for the insured institutions (this, after all, is why they demand and receive the government guarantees), bankruptcy for profit can easily become a more attractive strategy for the owners than maximizing true economic values.

…

Unfortunately, firms covered by government guarantees are not the only ones that face severely distorted incentives. Looting can spread symbiotically to other markets, bringing to life a whole economic underworld with perverse incentives. The looters in the sector covered by the government gurarantees will make trades with unaffiliated firms outside this sector, causing them to produce in a way that helps maximize the looters’ current extractions with no regard for future losses….”

Some observers may consider this phenomenon to be the same as their definition of a bubble, and so dismiss this post to being a matter of semantics, but I think this characterization of this episode is more revealing of the underlying forces. And it informs us more of what public policy should seek to do in response to the coming shakeout.

And of course, there is no reason that all three explanations could not be in play — namely that fundamentals (interest rates, unemployment rates), elements of a rational stochastic bubble, and looting all pushing up housing prices in an unsustainable fashion.

Technorati Tags: housing, bubble,

moral+hazard,

looting.

As, for instance, a shock to fundamentals that creates market buzz which looters, among others, might exploit. Could different T-horizons among rational traders at the time of the shock allow for some to have a rational expectation of appreciation at their intended exit, given the shock —which opens the door to all three effects— or are we strictly adhering to representative agents?

Thanks Menzie.

Most would call this the “moral hazard” debate. The market works because of its discipline of the actors. When the government short circuits this discipline it creates malinvestment. There are very few who actually seek bankruptcy for profit, but when conditions create a system where it pays to take extreme risks for extreme profits with no consequences is anyone really going to resist?

So when we talk of the “moral hazard” problem with housing and subprime what are we talking about?

blah blah blah. There is a bubble, it is bursting, period end of story.

pd130: In the models presented in the paper, there are types of agents, but within each class, they are the same.

DickF Your faith in the marketplace is inspiring. However, I think that even without government intervention, there has been and will remain examples of looting, as long as asymmetric information is a characteristic of the world. My question is — how does one know there are very few that would seek bankruptcy for profit? It could be that regulations properly enforced limit the extent to which looting occurs. When there is a patchwork quilt of (uneven) regulation, especially in the context of rapid financial innovation, looting is almost inevitable. (In a different context, see NBER WP 7091).

manhattangirly: Not a particularly illuminating perspective.

“In a bubble, borrowers are assuming they’ll have a capital gain on their house big enough to bail them out of the deep debt they’re getting into, …”

There is abundant evidence that that is exactly what’s been going on. Dean Baker of CEPR, in particular, has laid out in detail why the price appreciation has not been based on fundamentals of demography or income. That a vital enabling element has been the looting behavior described above doesn’t make it not a bubble, unless you want to argue that people were behaving “rationally” in response to it having become possible for people of uncertain future earning ability to buy enormously expensive assets with near-infinite leverage using teaser-rate loans. Since many of us out here who hold the conceit that we are rational consider it utterly irrational to believe that such insanity could continue for very long, and that it’s ending would spell doom for housing price appreciation, we consider this a bubble.

Well, part of the argument that US housing has not been a bubble has been that even though prices have been at all-time historic highs relative to income and rents, mortgage interest rates have been very low, and although they rose some in the past year or two, they have still not done so much, being kept down at least partly by the willingness of foreigners to buy US long term bonds, keeping the rates down that drive mortgage rates. So, blame the Chinese, like Brad Setser likes to do.

I noted in an earlier comment on one of these postings that both Kindleberger and Minsky argued that fraud is something that tends to emerge during a bubble. I have not done the numbers, but it looks to me rather like the use of subprime mortgages spread more after 2003 or so, well into the US housing bubble, if one assumes that it has been a bubble (my view, actually, I largely go with Baker and Shiller on this). They may have helped keep it going, allowing people to buy who could not otherwise have done so given the record high price-income ratios, but they (and the “looting” more genearlly) did not trigger it.

Regarding the rational stochastic bubbles, the model of Blanchard and Watson from 1982 that underlies this analysis assumes that the bubble must rise at an accelerating rate to provide enough capital gain to cover the rising risk of the inevitable crash, and that when the crash comes, it goes all the way back down to the fundamental suddenly, no “period of financial distress,” that Kindleberger saw in the majority of historical bubbles. Of course, JDH used the lack of such a sudden crash as evidence that this has not been a bubble.

One of the curious aspects of the rational stochastic bubbles is that at a certain point they go to infinity. The econophysicist, Didier Sornette has used this to forecast the crashing of bubbles. He has had a mixed record on that.

An example of a possible stochastic crashing bubble was in forex markets in Europe around 1990 and the German reunification, when there were definitely bubbles on some closed-end country funds, with the Germany fund going to premium of around 100% before crashing hard in the spring of 1990. For the exchange rate bubble, see “State-Space Estimation of Rational Bubbles in the Yen/Deutschemark Exchange Rate,” S. Kirk Elwood, Ehsan Ahmed, and J. Barkley Rosser, Jr., Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 1999, vol. 135, no. 2, pp. 317-331, and for an analysis of the bubble on closed-end country funds at that time see, “Complex Bubble Persistence in Closed-End Country Funds,” Ehsan Ahmed, Roger Koppl, J. Barkley Rosser, Jr., and Mark V. White, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, Jan. 1997, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 19-37.

Getting more to Menzie’s usual turf, that while one does sometimes see exchange rates collapse in crises, the wider swings that are sometimes suspected of being bubbly often do not do so. This would include the long upswing of the US dollar in the early to mid-1980s that simply was not supported by any fundamentals and went against the predictions of both the forward markets and all the experts for several years in a row. Wheh it finally turned around, it did not crash, but just went back down again in a pretty steady way.

This was an important part of the data in the famous 1990 paper by Charles Englel and Jim Hamilton that appeared in the American Economic Review on “Long Swings in the Exchange Rate…”, but on this blog more recently JDH backed off supporting the significant existence of such potentially bubbly long swings in the face of arguments in support of the random walk in forex markets by Menzie. Among those arguing that the dollar did bubble back then was Jeffrey Frankel, in his 1985 “The Dazzling Dollar” article in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity.

You seem to me making this all very complicated

>>Let me say that while I allow that there might have been a rational stochastic bubble in the housing market, I think that the gradual revelation of improper lending practices and excess risk taking in an environment of inadequate regulation suggests to me another interpretation

It is the very nature of a bubble that lenders buy into the idea that they too can bail out before the bubble bursts. Or in the feds case make adjustments to prevent collapse. Everybody feeding the bubble and feeding off it all believe together that they wont be caught when the music stops.

Greenspan was the maestro…….now look at the dork!

There’s a (prevalent) misconception here, key to the discussion about whether or not there’s a housing “bubble”: The problem with subprime loans is NOT that they were being used to buy too-expensive housing, thereby artificially “driving up” the price of housing to unsustainable levels.

Consumer watch-dog groups point out that the typical subprime loan is a re-fi on a pre-existing mortgage, NOT a recently-made loan to buy a house. Borrowers who were overloaded with debt outside of their mortgages re-financed, rolled-in the additional debt or cashed-out their equity, and wound-up with much larger mortgages (and un-manageable mortgage payments when the low “teaser” rates ended).

That might make this a subprime debt “bubble”, but NOT a housing bubble. Policy changes to address the looting, lax lending standards, etc., for subprime lending, SPECIFICALLY, might be in order, but not for housing generally.

There’s also no reason to think there’s going to be a housing “crash”, either. The subprime borrowers weren’t the ones “at the margin” bidding-up housing prices to the sky, because they weren’t buying houses, they were refinancing houses. Since they weren’t driving prices higher with their home-buying, they haven’t been driven out of the housing market by tighter lending standards, either. They simply aren’t that big a factor.

So who was driving housing prices higher, and who’s supporting them now (preventing a dramatic crash)? The better-qualified buyers in the mainstream. That would account for why the housing markets with the worst foreclosure rates and the housing markets with the most subprime loans are NOT the same. The areas with the worst foreclosure rates are the ones with the worst local/regional economies.

JDH’s original blog and the data supporting it are correct, with population, employment and other related fundamentals driving housing.

Sebastian

Are exotic loans and easy access to credit considered to be fundamentals too?

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=965068

I actually would also be interested in Professor Hamilton’s assessment of his colleague’s work.

Note: I have no economic background whatsoever.

So now subprime loans were not being used by first time buyers, flippers, criminals, and those who wanted to leverage to the max to get massive exposure to a bubble being created with the blessing of the powers that be who felt this was all new and wonderful??

And all of the above activity was only limited to the smaller subprime space and not prevalent in all sections of lending??

I suppose it is to be expected. Each bubble needs its sales people to encourage more fools to come along or enable them to bail while there is still time.

It is strange to me how those who point out reality are regarded as “excited” or somehow delusional or just unable to understand the finer points of mathematics and language.

I guess you all deserve what you get

Because the easy availability of sub-prime refinancings enabled over-extended borrowers to avoid foreclosure or sale, they reduced the supply of housing on the market. (A friend of mine who was nearly bankrupted by a spendthrift spouse was in exactly that situation.) Also, the percentage of subprime loans that were refinancings has certainly been elevated by refinancings of earlier subprime purchase loans. Moreover, we know that some subprime refinancings were done to buy “investment” properties.

As Dean Baker of CEPR has shown, there were no demographic underpinnings to this boom.

Menzie wrote:

“…how does one know there are very few that would seek bankruptcy for profit? It could be that regulations properly enforced limit the extent to which looting occurs. When there is a patchwork quilt of (uneven) regulation, especially in the context of rapid financial innovation, looting is almost inevitable.”

Menzie,

You answered your own question. The nature of government is that it creates “a patchwork quilt of (uneven) regulation.” To understand market motivation we must understand how and why the actors are paid. In the free market the actors are paid for providing a good or service to satisfy a need or want, but government employees are either paid in votes, or they are paid by the one who gave them their political appointment. What that means is that satisfying the needs of “customers” is secondary to covering for political reasons. The result is that regulations are a patchwork quilt depending on the whim of the politician or party in power.

With the free market you get choice on top of choice. In the government you get one size fits all.

This then provides an environment where the charlatan can reign.

Professor Chinn,

Your last line holds great promise, in my view:

“And of course, there is no reason that all three explanations could not be in play — namely that fundamentals (interest rates, unemployment rates), elements of a rational stochastic bubble, and looting all pushing up housing prices in an unsustainable fashion.”

I believe most reasonable people on this blog and elsewhere will agree that a comination of factors drove real estate prices well above trend.

I think Professor Hamilton painted himself into a corner by arguing that it was almost exclusively one of the three factors (fundamentals) that accounted for this run-up. He largely missed the importance of the other two factors until recently.

Going forward, I would suggest that a more balanced view taking into account the three factors you list (and others, as appropriate) would yield more light and less heat.

I would further submit that arguing “yes, there is a bubble” vs. “no, there is no bubble” produces little value.

Thanks, Menzie, have found the delicious paper.

I think Menzies is rewriting history a little in saying that Prof. Hamilton defines a bubble as prices in excess of discounted rental values. In the previous bubble thread we had the exchange below. Prof. Hamilton’s point was that any model capable of a solution based on fundamentals was not a bubble, whether or not that solution gave you something approximating discounted present value of rents.

“Is adaptive expectations an economic theory, by the Prof.’s definition? If adaptive expectations generate wild, predictable price gyrations (and I think they can), can we not call this result a bubble, because the expectations variable is endogenous?

If we can call the result a bubble, then doesn’t our current situation pretty much follow perfectly? In the flat lands, easy credit generates an increase in demand that doesn’t ramp up price, price expectations stay flat, and no bubble forms (but if the easy credit reverses itself, prices will drop, as housing is pretty much a putty-clay model). On the coasts, easy credit generates an increase in demand that does ramp up price, people cocnlude that since prices rose a lot last year they’ll continue to rise a lot, ramping up demand, hence price, even further, until a limit gets hit where the process hits a wall, prices flatten, the expectation disappears, and prices tank. Sure sounds to me like the San Diego or Miami Beach condo markets.

Posted by: mort_fin at March 24, 2007 07:52 AM

mort_fin, I would include adaptive expectations models (in which the expected price appreciation is a function of past price appreciation) as an economic fundamentals model, since, when you solve it out, the price is a function of the current and past fundamentals. A rational-expectations and adaptive-expectations model could behave similarly or could behave quite differently, depending on the parameters. However, when they behave very differently, one then gets into the further question of how the lenders of mortgages could base their expectations on something so far removed from what happens. And then I think you are getting back to the issue of possible market failure, which is where I’m trying to steer the policy discussion.

Posted by: JDH at March 24, 2007 08:11 AM

Sebastian and other seem to be making the point that since most subprime loans didn’t finance purchases, aggressive lending didn’t drive up house prices. There are several problems with this argument, starting with the fact that most loans, subprime or not, haven’t financed purchases. The % of subprime that are purchase isn’t the issue, it’s the % of purchase that are subprime that is the issue. Consumer advocates have stated that only 9% of subprime mortgages from 1998 (?) to 2006 were for first time home buyers. True, but less than 25% of the entire market was for first time homebuyers (I don’t have the exact percentages, but more than half of loans have been for refinancing, and less than half of purchase loans are for first time buyers), so that 9% of subprime for first time buyers could easily be 5% or more of extra first time buyer demand (by applying Bayes Theorem). And subprime is only one part of ‘expanded lending.’ Alt-A has also grown tremendously over the time period, and FHA moved in 1997 from 3% down payments to, effectively, no down payments. There is a lot of loosening that isn’t subprime that’s happened over the last 10 years.

As I recall, first-time buyers are typically about 30% of the market. I would expect a larger share of subprime borrowers among first-time buyers than among trade-up buyers.

Easier finacing was clearly a contributing factor to the frothy market. It was so in prior cycles as well. But the market would have been frothy without the loose lending – just a little less so.

The cycle peaks are driven by buyer exuberance. And buyer exuberance responds to price expectations much more than it dooes to lending standards.

When prices are expected to fall many people will be reluctant to buy without even considering the lending environment. When prices are rising fast many people will strive to buy with little concern for the borrowing costs.

All asset pricing cycles have some of this element. Some more so than others. Stocks and commodities are good examples of how this greed and fear can drive the market hard in the short run.

This speculator effect is mitigated in the housing market because the demand is mostly comprised of people whose fundamental need for housing will exist with or without the prospect of financial gain. Thus it is no surprise that housing markets rarely fall in a full year by as much as stocks sometimes fall in a single day.

The markets are very different, and the declines especially reflect that.

If there’s a bubble, it’s in people’s mistaken belief their house can appreciate 15% a year and never be vulnerable to a correction once it becomes over-priced. Honestly, popular media blows everything out of proportion whether it’s good news, or bad.

There is no bubble where I live but the media continues to tell stories of woe. Homes appreciate about 4% per year, here, and few have any illusions of making a fortune by over-extending their finances to “invest” in a house. Those few who do are, I suspect, strongly influenced by television, ignorance of basic personal finances, and predatory marketing; that is, first time buyers and a few trade-uppers.

So I say, “Bubble? What bubble?” This is just another case of wolves getting fat off euphoric sheep. I sincerely believe this country needs more regulation designed to prevent both individual and group stupidity.

MTHood said: “I think Professor Hamilton painted himself into a corner by arguing that it was almost exclusively one of the three factors (fundamentals) that accounted for this run-up. He largely missed the importance of the other two factors until recently.

Going forward, I would suggest that a more balanced view taking into account the three factors you list (and others, as appropriate) would yield more light and less heat.

I would further submit that arguing “yes, there is a bubble” vs. “no, there is no bubble” produces little value…”

Yes, but if there was ANY factor OTHER than “prices are going up because they’re going up” how could there have been a bubble?;)

The stock market offers us a lot more data on this than the slow-moving housing market. Every year, small-cap high-flyers go screaming up, then sell-off sharply, while big-cap stocks in mature industries rise at a slow-but-steady pace.

When the small caps go screaming up (think So. Cal. housing) but the big-caps (think North Carolina housing) just plug along at a more tortoise-like pace, is there a bubble, or anything at all out of the ordinary taking place? Or is this just the way money shifts around in a normal economy, from less-advantageous sectors/regions to more advantageous ones?

Sebastian

Anchoku must live in a very isolated part of the country that is not only immune from house appreciation but immune from the major city’s inhabitants that buy/sell products and services…none of which sell/are bought in Anchokuville.

I wouldn’t call this “stupidity”, but illustrative of that all too common predisposition to call something that doesn’t immediately impinge on one’s life as somebody else’s problem.

Economics: social threads connecting otherwise isolated hermits.

“The bubble” is clearly a multi-faceted story with a lot of particpants. It’s kind of like a macroeconomic “Smackdown.” I liked this line particularly.

“The looters in the sector covered by the government guarantees will make trades with unaffiliated firms outside this sector, causing them to produce in a way that helps maximize the looters’ current extractions with no regard for future losses….”

You may have noted that Moody’s and S&P have been loath to revalue tranched collateralized debt obligations (COD) and associated derivatives of mortgage based securities for banks and other registered big-wheels. Any downgrading or suggested downgrading of the more recent squirrelly bond tranches with a high degree of less-than-prime paper will cause massive discomfort for many whose risk-aversion has so recently been trumped by greed.

Note this yesterday from Bloomberg:

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601009&sid=aszosOrxVmjk&refer=bond

In discussing swaps, derivatives and other unregulated arcane, the article has this interesting line, “…models “were developed using the data that was available at the time,” such as transactions backed by cash collateral. Moody’s is now working on a research project to reassess the correlation between CODs at time when exposures can be “infinitely replicated.” Scary.

To paraphrase the Smothers Brothers, “bubble or looting…take your pick.”

I do think that part of whether there is a bubble or not shows up in attitudes, people buying simply on the expectation that prices will keep going up, even though the initial impetus to the increase may have been based on a fundamental. In the more rapidly rising markets we did read of such stories, people buying out of “panic” that they would soon not be able to afford a house, or the “flippers,” who seemed to be more prevalent in the condo market, which in the Washington area has declined pretty substantially in price, compared to other parts of the market, arguably bubblier.

An aspect of this relevant to the subprime issue is that lenders were probably caught up in this. It is fine to talk about looting, but presumably lenders do not want to make loans that are going to get defaulted on, as is widely happening now. They got taken in by the expectations of continuing price rises, which would allow people to refinance and thus not face the consequences of borrowing on the basis of such flakey mortgages.

I note, from following the markets in the Washington area, that the increase in exotic mortgages came late in the game. In 2003 there overwhelming majority of mortgages were “conventional” of one sort or another. But by early 2005 a majority were of the interest-only or some other variation on a sub-prime type.

Lenders, like other larger enterprises, fall victim to their own exuberance and the disconnect between intelligent strategy and the pursuit of simple performance goals. So planning and performance goals are set based on the profits and market conditions of the recent past. After a period of rising excess/easy profits a company will set aggressive revenue goals to gain more of those profits.

More profits are expected to result from more revenue. So the executives see that their compensation is connected to revenue growth even if their bonuses are not explicitly pegged to achieving those revenues. As they assertively and optimistically go after rapid revenue growth they sacrifice the very quality and discipline that enabled the previous high profit margins. The increased supply of product drives prices or standards down. Deterioration of profit follows.

I take issue with Sebastian’s comment on the impact of using subprimes to refinance, rather than purchasing. It is true that homeowners don’t do anything to bid up the price when they refinance, however, their refinancing with subprimes tells you a lot about the mentality of the borrower and the lender. Part of the reason that borrowers have been willing to do this is they think that the equity in their house will increase as it has over the past 10 years. And there’s good reason to believe that they took out an oversized mortgage to begin with because of their expectations of capital gain. Similarly, lenders get in the game because they’re willing to make the same bet on the home equity. Arguing that a bubble in the subprime debt market doesn’t tie into a housing bubble is like saying the junk bond bubble didn’t tie into the tech bubble. Excessive borrowing and lending against an asset occurs because of unhinged expectations about the future value of that asset. Namely housing.