Professor Lutz Kilian of the University of Michigan has an interesting new paper on the historical determinants of crude oil prices.

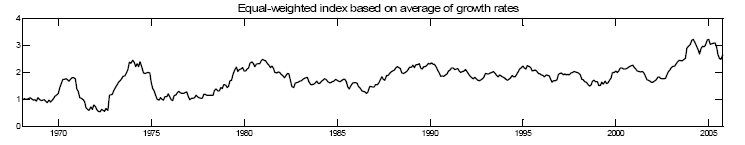

One of Kilian’s contributions is to develop a new time series based on the changes in the dollar price per ton of dry cargo shipping, displayed below. Tim Duy is among those already making use of the related Baltic Dry Freight Index. Shipping rates often start to climb sharply in the later stages of an unusually long or strong global economic boom, because of the long lead time required to build new ships. This index shows several upward surges in the 1970s and a more recent climb during 2003-2005.

|

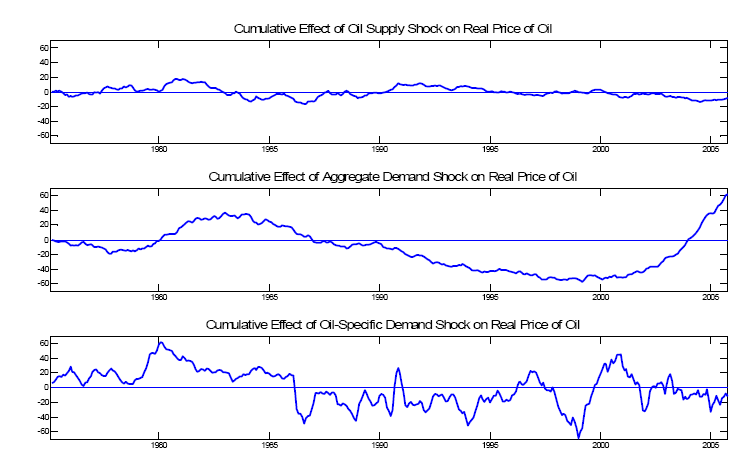

Since mining is also subject to long lead times, Kilian’s series gives a useful way to measure the contribution that variations in the level of global aggregate demand may make to commodity prices generally. Kilian looked at the extent to which fluctuations in the real price of oil could be explained statistically by the deviation of the series above from the CPI and a long-term time trend. The resulting predicted oil price swings are given in the middle panel below. The top panel isolates oil price changes that would be predicted on the basis of fluctuations in the total quantity of oil produced, while the bottom panel tracks the residual. Kilian labeled this third series as the effect of “oil-specific demand shocks”, thinking of events such as the response of speculators to concerns about the possible future supply disruptions that could have resulted from Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990.

|

Kilian concludes that oil supply disruptions have been less important than either of the other two factors in accounting for movements in the real price of oil. He attributes the broad trends of falling real oil prices in the 1990s and the run-up since 2001 primarily to global aggregate demand, whereas he believes that the sharp price spikes in 1979-80 and 1990 resulted from speculative demand.

Kilian then goes on to show that while oil price increases that result from supply disruptions or speculation tend to depress U.S. GDP, oil price increases that result from global demand factors are actually associated with stronger U.S. real GDP growth in the first year of the shock, though they later can be followed by slower GDP growth. Kilian also finds that demand-led oil price increases appear to be associated with an increase in U.S. inflation rates.

In other words, inflation, not recession, should have been the Fed’s major concern about the effects of oil prices during 2005.

For the record, my main concern in 2005 was recession, not inflation. And I was wrong.

Also for the record, my main concern in 2007 is still recession, not inflation.

Technorati Tags: oil,

oil prices,

commodity prices

JDH,

With the current methodology of the FED how can you separate inflation from recession? While demand of course has an influence on oil prices the huge swings seem to correlate much more closely to inflation as manifest in gold prices. The FED methodology actually does not allow them to affect liquidity until they drive the economy into recession and for this reason the FED response to inflation is closely related to recession.

DickF, I agree with some of what you’re saying, though I would express it a bit differently. I agree that when the Fed is excessively expansionary, it then puts itself in a position of needing to contract to fight the inflation it created. That contraction can be an important factor in producing the next recession. This looks to me like a reasonable description of at least part of the problem we’re in currently.

You should get essentially the same results from the CRB index of industrial material prices — it excludes oil — since it has a tight correlation with the dry dock index.

Of course this just reinforces Kilian’s conclusion.

Your readers may be interested in a post over at SeekingAlpha where Phil Davis is of the opinion that recent oil price increases are due more to speculative activity; a thesis based on data showing massive increases in oil futures trading volume.

What about the fact the oil supplies are dwindling? I know people here know of peak oil. Check out some hard data folks. The largest five oilfields in the world are declining and the most important, Ghawar in KSA, is starting to decline. They are down 8% from 2005 in 2006. They are on track for a near 12% this year and this is despite a TRIPLING in total rig counts. I’m sorry, it’s over. Speculators may have increased volatility, but dwindling supplies will trump all this.

thefinancedude,

We’ve reached peak processor speed for chips using silicon processes. INTC is down 20% since mid-January. I’m sorry, it’s over. Fastercomputers are a thing of the past.

So true, Name.

“Peak oil” is about running out of cheap oil, not about running out of petroleum period.

JDH: “I agree that when the Fed is excessively expansionary, it then puts itself in a position of needing to contract to fight the inflation it created. That contraction can be an important factor in producing the next recession.”

This sounds to me much like the chatter from long ago about the Fed driving with one foot hard on the accellerator and one foot on the brake, employing each with much force.

What happened to gradualism, and public announcement of Fed policy? Are they not possible in this wild world of speculative frenzy?

What ought the Fed to do? Maybe you’ve covered it before, but I for one would like to know what you recommend, James, as you worry (again) about recession.

Dave Iverson said: “What happened to gradualism, and public announcement of Fed policy? Are they not possible in this wild world of speculative frenzy?…”

Dave, in looking at Fed activity over the past four decades and comparing it to subsequent economic behavior, this looks like it’s about as gradual as it ever gets.:)

The problem doesn’t seem to be with how gradually it moves or how it communicates its intentions but with when it moves, it never seems to be pro-active in the right policy direction. The Fed doesn’t ease until the economy is clearly headed into the tall grass and it doesn’t remove the easing until the recovery is well under weigh.

Sebastian

Pardon my intrusion please. I read JDH regularly but have posted only once before. I’m asking for a favor this time. Can anyone advise the correlation coefficient of crude and diesel price — or the increase in diesel price for a dollar increase in crude? I’ve Googled without success. I need it to plug into a model of truck versus rail competition. Thanks for any help

I’ve just given the paper an initial read, and I’m not at all persuaded by his justification for ignoring the cost of fuel oil as an input to shipping rates (and it seems to me that the rest of his conclusions will fall apart if this assumption doesn’t hold because his supposed “aggregate demand” variable will be significantly contaminated by supply side issues). He relies on a detailed comparison of a very short period in 1970-1974, and some hand-waving discussions of other periods that don’t look consistent with the data to me at a first glance. I will research it further…

One way to think of this result is to look at the middle curve, which captures most of the movement in oil over the past two decades, and to realize that similar patterns are seen in many other commodities. Look at copper prices and you see much the same pattern. The story there is relatively uncontroversial, of new demand which has built up much faster than was anticipated, outpacing supply. JDH himself has made this point in the past (can’t find the post right now). This new paper seems to establish more rigorously that most of the oil price rise can be explained on the basis of rapid global economic growth leading to demand increases, rather than supply shortages.

So some quick news.google.com research on “bunker fuel prices shipping rates” turns up a bunch of stories like this one from Dec 2005:

and this one from May 2006:

and

So Professor Killian’s claim that “There are several reasons to think this is not quantitatively important” (p10) seems, at a minimum, worthy of further investigation. I’m not saying that what companies say to journalists is always to be taken at face value. Still, I think the possibility that the rise in shipping rates in recent years represents in part rise in input costs, rather than solely rise in aggregate demand, needs to be treated a lot more carefully than Professor Killian has treated it in his paper.

It’s also striking that his measure of “aggregate demand” goes up in response to the Iranian revolution oil shock, rather than down. Check his Figure 3 (bottom panel) which spikes up in early-mid 1979.

Stuart,

I am not sure if this is relevant to your point about bunker fuel, but I did want to let you know that the quotes you cite above refer to container shipping, which has a significantly different business model than dry bulk shipping.

Most dry bulk shipping companies do not have much direct bunker exposure, and in times of high freight rates, what they do have is basically passed on to customers.

Unlike container shipping, a large portion of dry bulk shipping is done on time charter contracts in which the leasee bears all bunker costs. In the case of spot contracts (or voyage charter) the fleet owner does bear bunker costs. It is difficult to estimate what percentage of dry bulk shipping is done on time versus because it varies greatly based on market conditions.

You would do better to look at the financial statements of pure dry bulk shippers such as Pacific Basin (http://www.pacbasin.com/), Dry Ships (http://www.dryships.com) or Precious Shipping (http://www.preciousshipping.com).

A pretty good update on surging dry bulk freight rates can be found here: http://www.dryships.com/index.cfm?get=report

I don’t have time to digest this discussion, but do know quite a bit about dry bulk shipping and will be happy to track down and send any further data you need.

Wogie — go to the BLS (BLS.GOV) and look in the PPI

for data on diesel prices — it will be indexed rather then the actual prices but this will work for your purposes. You can get crude oil prices at EIA.gov and they may have the diesel prices you need. The PPI probably also has crude oil prices. the data will be monthly but that should be OK.

Thanks, Spenser — but that won’t quite do it. Guess I’ll have to go to work and regress WTI crude on diesel prices. I’m using a truck-to-rail diversion model to test the effect of a permanent doubling of oil price. Standard 5 axle semi gets between 5 and 6 miles/gallon — rail intermodal much more. If you’re interested, the model documentation/user manual can be found here:

http://www.fra.dot.gov/downloads/Policy/ITIC-IM%20documentation%20v1_0.pdf

Intel is indeed down because technology has resulted in a glut of ever more powerful processors that they have to sell ever more cheaply.

And the oil industry? Mirror image to me.

More specifically, it comes all down to physics.

Microchips and electronics are actually a rare exception in the technology world. In 1960, the beginning of the modern semiconductor era, practical technology was extremely far away from fundamental limits, i.e. the sizes of atoms. There was enormous “headroom” left in the laws of physics to pursue great improvements. And it happened. (Richard Feynman foresaw this, “there’s lots of room down there”)

Energy and transportation are the other way around. Already existing technology is reasonably close to fundamental limits. Oil is of course fundamentally restricted by immutable geology. Technology might help us find more of what’s there but unlimited deployment of technology hasn’t done anything to bring out lots more oil in Texas. The oil fields that won WW2 for the Allies now produce 99% water. No 3d seismic computers is going to turn it around. Ever.