What does the empirical literature say about the sources of inflation movements in an era of globalization?

In a recent paper, Borio and Filardo of the BIS fire an opening shot in the debate over the best way to envisage the inflation process. In line with the view that the world is becoming ever more integrated along a number of dimensions, they conjecture a qualitative change in inflation dynamics. In “Globalisation and inflation: New cross-country evidence on the global determinants of domestic inflation”, they summarize their results thus:

There has been mounting evidence that the inflation process has been changing. Inflation is now much lower and much more stable around the globe. And its sensitivity to measures of economic slack and increases in input costs appears to have declined. Probably the most widely supported explanation for this phenomenon is that monetary policy has been much more effective. There is no doubt in our mind that this explanation goes a long way towards explaining the better inflation performance we have observed. In this paper, however, we begin to explore a complementary, rather than alternative, explanation. We argue that prevailing models of inflation are too “country-centric”, in the sense that they fail to take sufficient account of the role of global factors in influencing the inflation process. The relevance of a more “globe-centric” approach is likely to have increased as the process of integration of the world economy has gathered momentum, a process commonly referred to as “globalisation”. In a large cross-section of countries, we find some rather striking prima facie evidence that this has indeed been the case. In particular, proxies for global economic slack add considerable explanatory power to traditional benchmark inflation rate equations, even allowing for the influence of traditional indicators of external influences on domestic inflation, such as import and oil prices. Moreover, the role of such global factors has been growing over time, especially since the 1990s. And in a number of cases, global factors appear to have supplanted the role of domestic measures of economic slack.

The basic intuition is laid out quite clearly:

The globe-centric approach… sees goods produced in different countries as very close substitutes. In addition, it assumes that labour characteristics and capital mobility are such that factor input markets are closely integrated globally. Indeed, the possibility of shifting capital, and hence also “country-specific” know-how, across borders helps to underpin the greater substitutability among goods produced in different locations.

This view … implies that a mapping between country-specific excess demand and a country’s price inflation is not fully justified. It is global excess demand for the goods in question that is relevant. For a given product, it would make little sense to infer excess demand conditions from those in specific countries, as the tightness or slack could be offset by conditions elsewhere. Low demand in one country could be offset by high demand in another; limited supply in one by more ample supply in another. And what is true for a given product is also true, by implication, for any subset of products. The only difference is that mobility of labour and possibly capital across the subset can help to relieve sectoral price pressures, regardless of borders. In fact, in the limit, with country-specific factors irrelevant, but with imperfect substitutability across products, a globe-centric approach would point to aggregation of excess demand by products rather than by country.

…

There are several other implications of this alternative view, but I believe this is the most salient of the empirical implications. The operationalization of this view involves the augmentation of a standard Phillips curve specification (see this post on globalization and the Phillips curve) with a “global” output gap variable. In this case, the authors use a broader aggregate than in previous studies, encompassing 10 trading partners, or the world, depending upon the weighting scheme (trade, exchange rates, or PPP).

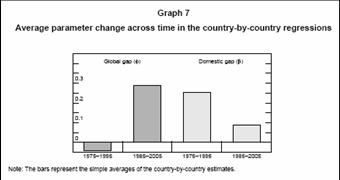

Defining their inflation variable as the excess of headline inflation over HP-filtered core inflation, Borio and Filardo find declining importance of domestic slack variables, and increasing importance of foreign, in a sample of 16 OECD countries. This central result is highlighted in these figures.

Chart 6 from Borio and Filardo, “Some Globalisation and inflation: New cross-country evidence on the global determinants of domestic inflation,” BIS Working Paper No. 227 (May 2007).

The foregoing are apparently startling results. Ihrig, Kamin, Lindner and Marquez (2007) investigate the robustness of the results obtained by Borio and Filardo, and obtain strikingly different results. From the conclusion to “Some Simple Tests of the Globalization and Inflation Hypothesis”:

[W]e estimated standard Phillips curve inflation equations for 11 industrial countries and used these estimates to test several predictions of the globalization and inflation hypothesis.

By and large, our findings suggested that the evidence for that hypothesis is surprisingly weak. First, the estimated effect of foreign output gaps on domestic consumer price inflation was generally insignificant and often of the wrong sign.

Second, although we replicated earlier findings that the sensitivity of inflation to the domestic output gap has declined over time in many of these countries, we found no conclusive evidence that this decline owed to globalization. The countries where the role

of the output gap declined the most were not those where openness to trade had increased the most, nor did measures of trade openness significantly affect the sensitivity of inflation to output gaps in our econometric equations. Finally, our econometric results provided, at best, only weak evidence that the responsiveness of inflation to import prices has been important, has increased over time, and has been influenced by increases in trade openness.

Since the two sets of authors examine essentially the same data, this seems at first gloss a remarkable divergence. Different treatments of estimating output gaps, and aggregating those gaps to world-level variables, can explain some of the difference. But the divergence is most likely driven – as Ihrig et al. point out – by the more standard definition of the inflation variable: the actual level of headline inflation (and including a distributed lag of past inflation to proxy for expected inflation, assuming adaptive expectations).

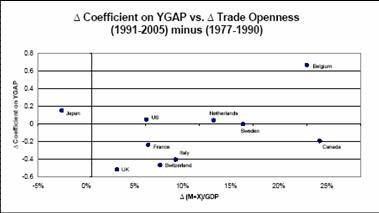

Ihrig et al. also observe that the decline in the importance of the domestic output gap does not seem to be directly related to easily observable measures of internationalization. For instance the change in the sensitivity of inflation to the lagged output gap between the two superiods is essentially uncorrelated with changes in trade openness, as measured by the sum of exports and imports divided by GDP.

Fig 2a from Ihrig, Kamin, Lindner and Marquez, “Some Simple Tests of the Globalization and Inflation Hypothesis,” International Finance and Discussion Paper No. 891 (June 2007).

The authors do not deny a possible role for trade internationalization in modifying inflation dynamics.

As economies around the world are increasingly tied together by trade and other economic linkages, it is plausible that foreign developments should play an increasingly important role in determining domestic inflation. Accordingly, we were surprised by the weakness of the evidence for the globalization and inflation hypothesis. Our results may be telling the truth: that inflation has not become as globalized as some observers would assert. For example, structural rigidities in some economies may be impeding the response of the price setting process to globalization.

However, it is also possible that international conditions are becoming more important to the inflation process, but it is difficult to discern this effect in the data. In particular, as inflation throughout the industrial economies has in recent years become less variable and subject to fewer large shocks, it may have become harder to identify econometrically the effects of foreign developments on inflation. Indeed, to the extent that monetary policy has succeeded in better anchoring inflation expectations in recent years, this may have led inflation to become both less variable and less sensitive to resource utilization and relative prices, potentially offsetting the effects of globalization

.

Finally, the process of trade integration has been ongoing for much longer than the past

15 years; therefore, it is entirely possible that the impact of globalization has not been confined just to that most recent decade and a half, and a longer period than we have studied may be required to identify its evolving impact on inflation. In any event, more research in this area is indicated.

Although we did not find evidence that globalization had altered the parameters of the inflation process, we did uncover indications that globalization had affected one of the inputs into that process, the output gap. Over time, net exports appear increasingly to have attenuated the linkage between domestic demand and real GDP—the correlation between the two has declined in most industrial economies, and net exports have generally become larger as a share of GDP. This suggests that net exports have either helped to stabilize real GDP, output gaps, and inflation for given trajectories of domestic demand or, alternatively, have allowed domestic demand to fluctuate more widely without destabilizing GDP and inflation in the process.

In other words, if the Ihrig et al. view of the world is correct, then the channels by which global factors influence domestic inflation might be more subtle than the obvious ones.

Technorati Tags: Phillips curve,

exchange rates,

output gap,

inflation gap,

Taylor rule,

globalization, and

inflation expectations

Menzie (Borio and Filardo) wrote:

This view … implies that a mapping between country-specific excess demand and a country’s price inflation is not fully justified. It is global excess demand for the goods in question that is relevant. For a given product, it would make little sense to infer excess demand conditions from those in specific countries, as the tightness or slack could be offset by conditions elsewhere. Low demand in one country could be offset by high demand in another; limited supply in one by more ample supply in another. And what is true for a given product is also true, by implication, for any subset of products. The only difference is that mobility of labour and possibly capital across the subset can help to relieve sectoral price pressures, regardless of borders. In fact, in the limit, with country-specific factors irrelevant, but with imperfect substitutability across products, a globe-centric approach would point to aggregation of excess demand by products rather than by country.

If you begin with an incorrect assumption then it is not possible to get a correct answer. Inflation and deflation are monetary not fiscal. Supply factors are fiscal.

Imports and exports should have virtually no impact on inflation or deflation of a domestic currency. For products to be imported they must in the currency of the importing country so monetary effects from the exporting country are virtually eliminated in the exchange.

Today inflation and deflation are determined by the monetary authorities of the country issuing the currency, but often smaller economies find that they must tie themselves to the currency of a larger economy because of import/export exchange. The result is that an economy like the US economy drives inflation/deflation around the world often with exaggerated results (see Argentina and Brazil in the 1970s).

Like so much of Keynesian economics the Phillips curve confuses cause and effect. The late 1970s proved the error.

DickF,

While I applaud your answer to dryfly in the previous post & the your basic thrust above, I think this post raises a very interesting question.

When Asian central banks create lots of Yuan & Yen & use them to buy 10-yr Tresuries & hulking quantities of raw commodities, they are affecting the prices of huge number of goods consumed by Americans. They played a significant part in the housing bubble & undoubtedly contribute to the high prices of oil, metals, coal, grains, etc.

In the long run, one might suppose the value of the domestic currency would be purely a function of domestic productivity & domestic money supply. But in terms of what the CPI measures in a given year, the rest of the world surely matters.

algernon,

Can the Asian central banks buy US treasuries with foreign currency or must it be in dollars?

When Asian central banks create lots of Yuan & Yen

Okay, the Japanese are creating a lot of yen. No doubt about that, it drives the carry trade.

But why do the Japanese have such low inflation? With that much currency being created, with the yen falling relative to the dollar, why are they still in a deflationary environment?

Buzzcut,

That is an excellent question. My conjecture is that the Japanese are using it (plentiful Yen) primarily to lend to foreigners (purchasing US or New Zealand debt) rather than purchasing domestic goods.