Some delayed reflections on the May import/export price release, and how to interpret the data in light of the empirics of exchange rate pass through.

From Bloomberg:

U.S. Import Prices Rise More Than Forecast in May (Update2)

By Shobhana Chandra

June 13 (Bloomberg) — Prices of goods imported into the U.S. rose more than forecast in May on higher prices for oil and industrial supplies driven by strong overseas demand.

The 0.9 percent increase in the import price index followed a 1.4 percent gain in April, the Labor Department reported today in Washington. Prices excluding petroleum rose 0.5 percent and prices of consumer goods were unchanged.

Prices of industrial materials such as metals rose for the sixth month in seven. Federal Reserve policy makers, who call inflation the biggest risk to the economy, said at their last meeting that faster growth abroad and the decline in the U.S. dollar are adding to price pressures.

“Inflation is going to remain a concern for a considerable period of time because of global growth and demand for commodities,” said Russell Price, senior economist at H&R Block Financial Advisors in Detroit, whose firm forecast a 0.8 percent import price gain. “But I don’t think it’s going to develop into an actual problem.”

…

Weakening Dollar

The dollar, which has weakened about 6 percent since the beginning of last year against a trade-weighted basket of currencies of major U.S. trading partners, is making imports more expensive.

The cost of imported capital goods were unchanged last month and were down 0.1 percent from a year earlier.

Prices of imported automobiles, parts and engines rose 0.2 percent and costs for imported consumer goods excluding autos were unchanged.

Bridgestone Corp. and Michelin & Cie., the world’s two largest tiremakers, have raised prices after higher costs for natural rubber and oil products squeezed profits.

“In the coming year we’ll continue to operate in the context of high raw materials costs,” Chief Financial Officer Jean-Dominique Senard told shareholders at Michelin’s annual meeting May 11. Competition will be “fiercer” this year.

The jump in prices, relative to the depreciation in the dollar, is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Log nominal trade weighted dollar exchange rate against broad basket of currencies (blue), price of all goods imports (red) and non-oil imports (green), rescaled to 2002M02=0. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FREDII, BLS import/export price release, and author’s calculations.

Typically, people make the linkage between exchange rate changes to import (and export) prices, and from import prices to the general price level. Certainly there is some truth to this transmission channel. As discussed in this post, there does seem to be a decline in the pass through at both the import price stage (see this Fed working paper [pdf]), and the import to general price level.

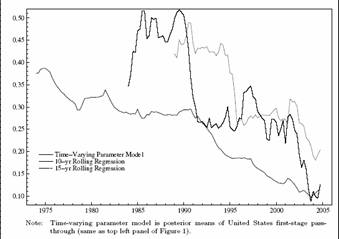

This paper by T. Sekine [pdf] documents the reductions, using a time-varying parameter approach (the coefficients are assumed to follow a unit root process). The results for the first stage contrast somewhat with the rolling regression approach adopted in the Fed study cited in this post, in that the decline in pass through is more gradual.

Figure 2: Time varying parameter estimate of exchange rate pass through to import prices for the US, and rolling regression coefficients for 10 and 15 year windows. Source: T. Sekine, “Time-varying exchange rate

pass-through: experiences of some industrial countries,” BIS Working Ppaer No. 202 (2006).

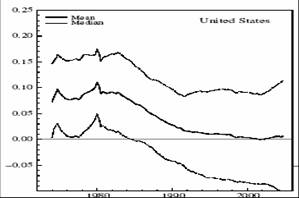

The evolution of the extent of pass through to the general price level is shown in the next figure.

Figure 3: Median estimate of import price pass through to consumer prices for the US, and posterior interquartile range of estimates. Source: T. Sekine, “Time-varying exchange rate

pass-through: experiences of some industrial countries,” BIS Working Ppaer No. 202 (2006).

Sekine concludes that the decline in second stage pass through is largely correlated with the decline in inflation. On the other hand, across industrial countries, the decline in first stage pass through is associated with primarily greater import penetration. The US decline does appear to be related to lower inflation.

The fact that pass through varies with inflation is a strong reminder that import prices, general prices and exchange rates are all jointly determined, so that pass through cannot be considered a structural parameter.

So, if inflation were to rise, measured exchange rate pass through would also likely change. That would seem to be the end of matters, but Bailliu and Fujii, in a careful panel econometric study [pdf], observe that the decline in inflation in the 1980’s was not associated with a similarly marked decline in exchange rate pass through into import, producer or consumer prices, while that in the 1990’s was. In other words, not all inflation declines are created equal in terms of inducing a reduction in exchange rate pass through. They attribute the difference to the enhanced credibility associated with the 1990’s stabilization — although since credibility can not be directly observed, this is mostly informed conjecture.

If Bailliu and Fujii’s analysis is correct, exchange rate pass through will remain low as long as central bank credibility remains high.

In a related vein, Gagnon and Ihrig [pdf] attempt to link the change in pass through to parameters in an estimated Taylor rule for monetary policy. Specifically, they argue pass through should be smaller when the weight on inflation stabilization is higher; unfortunately, they are unable to find unambiguous evidence in favor of this hypothesis.

By the way, just when you thought you might understand pass through, I should note that there is some dispute over the stylized facts. Linda Goldberg and Jose Campa argue in this paper [pdf] that exchange rate pass through into consumer prices has actually increased, after accounting for changes in the composition of goods consumed, even if the sensitivity of import prices of some goods has decreased.

Technorati Tags: dollar,

exchange rate,

pass through,

import prices,

monetary policy,

credibility, inflation, Taylor rule..

Menzi wrote:

…not all inflation declines are created equal in terms of inducing a reduction in exchange rate pass through.

When we were on the gold standard gold was the world money and so exchange rate differences were meaningless, much like the difference between a dime in California and a nickle in Florida. With world floating currencies governments change the value of their currencies at will and create inflation or deflation on the backs of their citizens.

If you analyze pass through by considering only the domestic currency you are open to considerable error. Whether the domestic currency is inflating or deflating is actually meaningless. There is only meaning in the relative exchange rate differences in all currencies and that is dependent on the actions of the monetary authorities in all of the countries with exports or imports.

One country could be subsidizing exports to another country on the backs of its citizens through inflation that is higher than the importing country, but if the exporting country’s inflation is lower than the importing country then there may be no net subsidy.

Because of floating rates this pass through is virtually impossible to measure because inflation and deflation of nearly every central bank in the world is mixed into the inflation/deflation mess so that inflation/deflation in Japan effects the inflation/deflation of exports from Australia to the US depending on the Japanese components in the Australian export.

But even if it could be measured what would it mean? The mix of exchange rates is constantly changing. Which country is subsidizing which other country? Who knows?

Sorry, Anonymous is me and my finger stuttered.