Amidst all the discussion about rampant Chinese GDP growth, the appropriate conduct of macro policy in restraining that growth, and the implications for the components of aggregate demand, a simple question leads to complicated answers.

From the July 20 Wall Street Journal [sub. req.]

China’s GDP Climbs 11.9%, Escalating Pressure on Policy

By PAUL LUPINACCI

July 20, 2007

China is on pace for its fastest annual growth since 1994 and is almost certain to surpass Germany this year as the world’s third-biggest economy. But its headlong expansion runs the risk of an economic overheating that could result in rising inflation and bad investments from low interest rates — a situation that could bring about short-term economic pain.

China’s gross domestic product expanded 11.9% in the second quarter, on top of an 11.1% gain in the first three months, with officials pointing to the benefits to ordinary Chinese from such rapid growth: Urban incomes rose 14.2% and rural incomes 13.3% in the first half, some of the sharpest gains seen in recent years.

This development has spurred further action by the PBoC; it moved to raise interest rates yet again, to 6.57 percent (see here).

With these stories, and the discussion of how China has now overtaken Germany as the world’s fourth largest economy, it might be useful to step back and ask how reliable are these point estimates for Chinese GDP. Here, an article by Harry Wu, entitled “The Chinese GDP Growth Rate Puzzle” (published in Asian economic Papers 6(1); sub. req.) is instructive:

The Chinese statistical authorities recently revised the Chinese GDP level and real growth rate for the period

1993-2004 following China’s first national economic census for 2004. However, the methodology used in their revision is opaque. Using a trend-deviation interpolation approach, this study has managed to replicate the basic procedures of the revision and reproduced the official estimates. Through this exercise, we have found that the estimates that could be obtained by the straightforward interpolation procedures were significantly modified. Based on a political economy argument, we attempt to explain why the revision had to leave the growth rate of 1998 intact and why it had to bypass the price issue and directly work on the real growth rate revision. Based on previous studies and other observations, we also question the census results on nonservice industries.

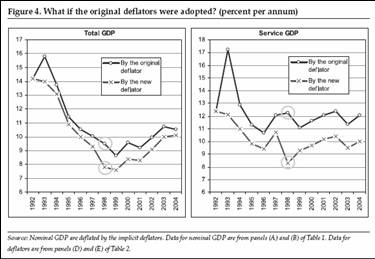

The bottom line of the paper is that trends in Chinese real GDP are suspect, if drawn far back enough. While the 2004 economic census is arguably the best measure of economic activity we have (capturing the previously underreported service sector), there are still questions surrounding the interpretation of these data. After all, manufacturing output was virtually unrevised, implying that this sector was well measured. Even more mystifying is the calculation of deflators; the decisions regarding these calculations seems, at least to Wu, to be driven by the necessity of not letting the 1998 (and earlier) growth rates be driven too far away from those previously published. The differing growth rates using the original and revised deflators and the new nominal GDP figures are shown in Figure 4 from the paper.

Figure 4 from Harry Wu, “The Chinese GDP Growth Rate Puzzle”, Asian economic Papers 6(1).

In other words, the process is one big black box. Now, it may be that some of the biases have decreased as pressure to restrain growth has increased. But as long as political pressures exist to massage economic statistics, one will have to take GDP announcements from China with some perspective.

More on Chinese statistics from Dresdner Kleinwort via Econocator. That report argues that data reliability has declined as resources for data collection have shrunk.

By the way, the need for adequate funding for accurate data collection, and insulation of the statistical agencies from political pressures, is a moral that we should all heed, including in the U.S. (think about the Administration’s attempt to eliminate funding for the SIPP, one of the few devoted to poverty related program participation. After all, to some, it may be if the phenomenon isn’t measured, it doesn’t exist).

Technorati Tags: China, GDP,

national income accounting,

Chinese trade surplus.

A China está, realmente, crescendo?

A metodologia usada pelo governo de Beijing é bem, mas bem duvidosa. Já foi assunto de discussão lá no Econbrowser antes. Claudio…

SIPP should get zip. Leave poverty amelioration to charities and communities.

China is going to have one heckuva mess on its hands during the forthcoming (actually, underway) U.S. recession. My gut sense has always been to be skeptical of the ‘world domination’ posited for China for 2025 or so (my money would be on India — democratic, English speaking, peaceful Hindus, etc.). Your post, Professor Chinn, confirms what my gut has been telling me.

“If the phenomenon isn’t measured it doesn’t exist” The availability and clarity of data on many government websites has suffered under this administration and under the Republican Congress. Transportation, energy, poverty, and race data are examples.

Menzie wrote:

…the appropriate conduct of macro policy in restraining that growth…

When an article begins with using macro policy to restrain growth I look for the overseer who bleed George Washington to death. Should we wonder at the hubris of economists determining for others at what level they should satisfy their wants and needs?

WSJ wrote:

China is on pace for its fastest annual growth since 1994 and is almost certain to surpass Germany this year as the world’s third-biggest economy. But its headlong expansion runs the risk of an economic overheating that could result in rising inflation and bad investments from low interest rates — a situation that could bring about short-term economic pain.

Can the WSJ point to one incident where growth actually caused inflation? China has been experiencing soaring growth for years close to a decade yet the world is crying out that the yuan is too strong. Does anyone find this hard to compute?

Inflation rears its ugly head when the government attempts to stimulate consumption by increasing the money supply without an increase in the supply of goods, not when an economy is producing more and more goods and increasing productivity.

Economics is not still called the dismal science for nothing.

Sorry Anon is me.

hmmm…these comments – I’d wish the the market cheer squad spend a bit more time reading their history books, specifically the section about the Canadians of New Foundland in the 1970s. I’m sure they easily topped 10% growth per annum for at least a decade – that is, until the cod fishery collapsed and the central government was helpless to keep the money flowing.

China not only takes great liberty with their statistics – they’re openly destroying their environment pursuing low profit, short-term growth in order to keep the workforce nominally employed.

I hope the newly right leaning countries like Australia, New Zealand and Canada are willing to open their arms up wide when hundreds of millions of Chinese need to be relocated. China seems to be in a big hurry to collapse thier own carrying capacity, a reality which is not reflected in the reported numbers.

As a Newfoundlander, I can say we had 10% growth 1972-1977, 1978-79, and 1980-81.

But I hardly think the case of China is comparable. Exhausting natural resources is a different situation than manufacturing.