As the dollar hits a new low against the euro [0], some thoughts on what arguments make sense, given our knowledge of the statistical properties of real exchange rates.

From Deutsche Bank’s Exchange Rate Perspectives (February 22).

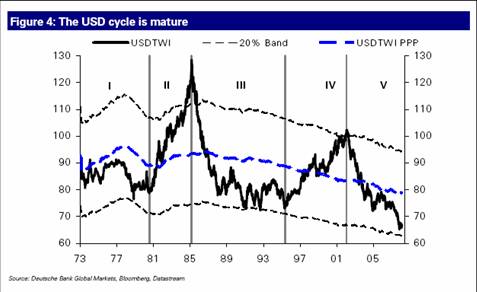

We see several themes pointing towards the current USD down cycle being close to an end:

- The USD is close to the bottom of its historical valuation bands

- We expect US growth to rebound in 2H 2008 with fixed-income and equity inflows into the US recovering in line

- Interest rate differentials should move in favor of the USD by 2H 2008, as we expect the ECB to start cutting rates during Q2

- The US trade deficit is narrowing

- On the view that oil and commodities prices are at or close to their peaks for this cycle, a slowing in emerging market reserve growth will slow the demand for euros

Given the arguments above, we believe that the USD is likely to bottom in 2008 (with the exception of USD/JPY). … the fact that [the] trade-weighted USD index is undervalued in PPP terms, and the cycle is now relatively mature, suggests the USD is close to a bottom.

I’m going to focus on the first point, which seems eminently reasonable, and seems validated by this graph:

Figure 4 from Deutsche Bank Exchange Rate Perspective (February 22, 2008).

I believe the blue line is the line implied by purchasing power parity (PPP), namely:

e = p* – p + c

where e is the log value of a currency (the inverse of the exchange rate), p and p* are the log price levels in the home and foreign countries, respectively, and c is a constant. Since p and p* are price indices and not price levels, one has to estimate the constant. The +/- 20% bands seem to bound the movements of the dollar.

If PPP holds in the long run, then the real currency value (in this case, of the dollar) should revert to a constant average value, or allowing for some omitted factors, to a trend. One can estimate the trend using OLS, to obtain the following picture (here I assume the DB TWI and the Fed’s index are similar):

Figure 1: Log real value of the dollar (broad), and 1973M01-08M01 trend. Source: Federal Reserve Board and author’s calculations.

However, as I’ve pointed out on a number of occasions [1], one has to be careful about estimating “trends”. One can always do it, but it might not always be a good idea. It turns out that there’s no “right” answer to whether in this case we should estimate deterministic trends (and hence assume that the real value of the dollar is a “trend stationary” process), or we should model the real dollar as a difference stationary process (a random walk is a difference stationary process).

The standard Augmented Dickey-Fuller test (optimal lag length selected by SBC at 1 lag, allowing for trend) fails to reject (the p-value is 0.76 using Mackinnon critical values). The Elliott-Rothenberg-Stock (1996) DF-GLS unit root test (allowing for a trend) fails to reject the unit root null, as do other tests (Phillips-Perron, etc.). On the other hand, a test with a trend stationary null hypothesis, namely the Kwiatkowski, Phillips, Schmidt and Shin (KPSS) test also fails to reject that null.

There’s good reason to expect PPP not to hold, certainly in the short run, perhaps even in the long run (see [2] [pdf], [3]). After all, consumption bundles are not identical, there are nontraded goods, and transactions costs can prevent arbitrage. But there is hope, in the sense of an intermediate view — that arbitrage kicks in when the real rate deviates sufficiently far away from the value implied by PPP.

From Taylor and Taylor’s survey of PPP:

In empirical work on mean reversion in the real exchange rate, nonlinearity can be

examined through the estimation of models that allow the autoregressive parameter to

vary. For example, transactions costs of arbitrage may lead to changes in the real

exchange rate being purely random until a threshold equal to the transactions cost is

breached, when arbitrage takes place and the real exchange rate mean reverts back

towards the band through the influence of goods arbitrage (although the return is not

instantaneous because of shipping time, increasing marginal costs, or other frictions).

This kind of model is known as “threshold autoregressive.”

While this concept of bands of inaction seems to accord well with the bands drawn in Figure 4 above, Taylor and Taylor also observe:

Using a threshold autoregressive model for real exchange rates as a whole,

however, could pose some conceptual difficulties. Transactions costs are likely to differ

across goods, and so the speed at which price differentials are arbitraged may differ

across goods (Cheung, Chinn and Fujii, 2001). Now, the aggregate real exchange rate is

usually constructed as the nominal exchange rate multiplied by the ratio of national

aggregate price level indices and so, instead of a single threshold barrier, a range of

thresholds will be relevant, corresponding to the various transactions costs of the various

goods whose prices are included in the indices. Some of these thresholds might be quite

small (for example, because they are easy to ship) while others will be larger. As the real

exchange rate moves further and further away from the level consistent with PPP, more

and more of the transactions thresholds would be breached and so the effect of arbitrage

would be increasingly felt. How might we address this type of aggregation problem? One

way is to employ a well-developed class of econometric models that embody a kind of

smooth but nonlinear adjustment such that the speed of adjustment increases as the real

exchange rate moves further away from the level consistent with PPP. Using a smooth

version of a threshold autoregressive model, and data on real dollar exchange rates

among the G-5 countries (France, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United

States), Taylor, Peel, and Sarno (2001) reject the hypothesis of a unit root in favor of the

alternative hypothesis of nonlinearly mean-reverting real exchange rates — and using data

just for the post-Bretton Woods period, thus solving the first PPP puzzle. They also find

that for modest real exchange shocks in the 1 to 5 percent range, the half-life of decay is under 3 years, while for larger shocks the half-life of adjustment is estimated much

smaller — thus going some way towards solving the second PPP puzzle.

So, perhaps there is some reason to believe that these “20%” bands have some formal empirical (read econometric) basis. If one believes that these threshold approaches, then another question arises.

The discussion is usually couched in terms of the view that the exchange rate, rather than prices, adjust. This view is consistent with the idea that asset prices move fast, in contrast to sticky prices. But as elaborated in papers by Cheung et al. (2004) , and Engel and Morley (2001) (in a one-regime context), prices often seem to do the adjustment.

Work by UW student Deokwoo Nam is informative in this respect; from the abstract to “Can the real exchange rate be stationary within the band of inaction?,” [pdf]:

We decompose the

real exchange rate into the nominal exchange rate and relative price by imposing the symmetry

assumption, and then model their dynamics as a bivariate Threshold Vector Error Correction

Model (TVECM). As expected by the evidence on nonlinearity of the real exchange rate, our

empirical results provide evidence on a threshold cointegration of the nominal exchange rate and

relative price. The surprising finding is that the roles of the nominal exchange rate and relative

price in correcting the deviation from PPP are distinct between outside and inside the band

of inaction relative to those in the linear framework. That is, it is only outside the band that

the nominal exchange rate makes its significant contribution to the correction of the deviation

from PPP. On the other hand, the correction by the relative price is insignicant outside the

band, but there is some evidence that the relative price makes its significant adjustment to the

deviation from PPP inside the band. This finding implies that it is the relative price, not the

nominal exchange rate, that corrects the deviation from PPP within the band, if the correction

is indeed made within the band of inaction.

Unfortunately, these results pertain to bilateral US real exchange rate; we don’t know how the aggregate trade weighted exchange rate behaves.

The bottom line: Maybe those bounds exist, but it’s not clear what — exchange rates or price levels — will do the adjusting to re-assert PPP.

Technorati Tags: purchasing power parity,

dollar,

threshold autoregression, exchange rates,

threshold cointegration.

All of this goes right out the window if you remove the medium of exchange from the equation.

Central premise, money is ‘representative wealth’ and money represents ‘real’ wealth/commodities.

Since geography is no longer a barrier to the movement of commodities (even perishable ones) all commodities in major markets should have equal ‘value’. A pound of chicken in Boston should cost the same as a pound of chicken in Beijing (because availability is no longer an issue.)

Yet this is not the case…if it were true the Chinese worker would starve to death! Or the reverse would be true, that food would only consume a tiny fraction of a US worker’s income…which is obviously not the case either.

So, what’s left? Obviously fraud, otherwise known as currency manipulation.

Seems to me the level of federal debt in the US is about twice per capita compared to Canada. The level of personal debt is also insane.

The banking system is in dire straights and interest rates are going up despite the fed trying to manipulate them down.

Everything is going to hurt, but where is the foundation? The US foundation has so many termites, it is amazing it continues to stand up.

I have a hard time considering touching anything US, just a foreigner’s perspective on why I don’t see the US dollar bottoming in 2008…

Until the yen hits a historical high against the dollar (between 80 and 90, right?) I will be unimpressed.

106 yen to the dollar is interesting, though. It seems that even the Japanese are having difficulty manipulating their currency to where they want it (probably 120). That’s is saying something. While the Japanese by no means invented currency manipulation, they sure have perfected it.

I guess my question to you of the intelligensia is, will there be a breaking point where the yen rises sharply? Will we go from 100 to 80 in a couple of days, maybe when the Japanese monetary authorities cry “uncle”?

As someone about to walk out the door to catch a plane to Siena for ten days, the new low of the dollar against the euro hurts.

I am struck by the received wisdom of forex markets mostly being random walk (you and your pals, Menzie), some technical trending stuff, with that little bit of PPP reversion hanging in there. Supposedly uncovered interest parity does not cut it.

But, as near as I can tell what has triggered this current plunge below 1.5 is Bernanke clearly signaling further interest cuts. Inflation targeting? Forget it. I fear that they fear much worse possible problems in the financial system as long as housing prices keep falling, so, save the banks with more interest cuts, even if dollar falls (helps those exports) and inflation goes up.

Dr. Chinn, your humor is not lost on us when you use [0] to make a link about the dollar! As an unfortunate dollar holder, I know just what you mean.

Seriously, though, there is a disconnect over Bernanke’s supposed concern over inflation and this helicopter drop of his:

“While we can’t do much about oil prices or food prices in the short run, we do have to be careful to make sure that those prices do not either feed substantially into other types of prices,” Bernanke told the Senate Banking Committee today. The Fed must ensure that the public remains “confident” that it will control inflation, he said.

As a statistician I am horrified at this supposed use of statistics. 20% bands seem to estimate the bounds of the dollar? Any decent statistician knows that this is completely ad hoc and doesn’t warrant any further consideration.

Ed is right, of course. Nevertheless, your blog provides informaion of important practical value. It may also provide some comfort to currency speculators, but they should be mindful of that 1985 spike. Markets have greater depth now, though, so a similar episode may not repeat.

I have not and do not support Ron Paul for President, but if you want to know about the dollar problem listen to this brilliant clip of Ron Paul and then BB’s almost insane reply from yesterday. Please don’t ignore this out of prejudice against Ron Paul. Listen with unbiased ears and a reasonable mind.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yybFGh1sUcQ

Bernanke trys to justify his horrible job of stabilizing the value of money by saying he must focus on prices, then he has to admit that even looking at prices he is an utter failure. What is sad is that this is going to get worse.

Gegner: I think you’ve assumed zero transportation and transactions costs. This is clearly not the case — see this post.

Buzzcut: Not sure what you mean here — the Japanese have not been intervening in forex markets for about three years. For sure, they were intervening massively before that.

Barkley Rosser: I don’t think the exchange rates a random walk. I think there’s serial correlation in changes, and I think there is some predictability in nominal rates. However, the noise-to-signal ratio is high, and often predictability is hard to exploit in a profitable fashion.

Emmanuel: I think it is hard to disentangle the relative price shifts in the dollar’s value from the price level effects. But I agree that one could plausibly argue that inflationary expectations are a bit less “anchored” than they were a year ago.

Ed: I wasn’t arguing for 20% bands; but in any event, the investment bank’s objective function is different from the statistician’s. You and I might want to minimize the sum of squared errors (and hence use a SETAR model), they want to time trading to maximize profits.

Don: Thanks. You might find this post on an alternative measure of the dollar’s value of interest.

I think I understand your answer to Buzzcut re the Japanese not intervening in forex the last 3 years. However, maintaining an interest rate of .5% is hard to conceive of as neutral.

I just read that on the Chicago Exchange floor they were cheering Ron Paul as he questioned Bernanke. Perhaps I am too pessimistic.

Gegner: there’s also the Balassa-Samuelson effect. In practice, the price of a pound of chicken bought in Boston (or Beijing) also includes substantial non-tradable components such as land rent and the cost of local labor. The price of purely tradable goods is much more uniform.

The Balassa Samuelson effect also occurs between richer and poorer areas of the same country, so it’s not explained by currency manipulation.

Deborah says: “Seems to me the level of federal debt in the US is about twice per capita compared to Canada. The level of personal debt is also insane.”

It depends a bit on how you measure govt debt, net vs gross, per capita or per unit of GDP, etc, but the US is about at the average national govt debt level for the G-7 by most measures. And the US has much more favorable demographics than most of the G-7. Canada used to have much higher debt measures but has brought them down considerably in the last 15 years. Still, I don’t see that the US debt situation is any worse than most other industrialized countries. I could be convinced otherwise, but those are my views from a casual look at the data.

I believe that most of the “nightmare” scenarios about US debt levels assume that US medicare costs will continue to grow strongly, without bound. As these costs grow, there will be more political pressure to contain them. See Herb Stein’s law: What can’t go on forever, won’t.

You seem to assume there is some sort of naturally occurring floor on how low the dollar can go. Maybe this is the beginning of a decades long slide as happened to the British Pound.

algernon: True, that’s not a conventional monetary policy. But then we start getting into the area of arguing that changing interest rates is a way of “manipulating” exchange rates. One could define manipulation that way, but it is somewhat different from the way the term is conventionally used.

guest: That’s a good point. Typically, if productivity growth is more rapid in tradables, then countries with higher income levels will have stronger currencies in price adjusted terms. This effect relies upon the presence of nontradable goods.

Chris Neely: I concur; a proper evaluation of the debt effect would examine the amount of debt in the private sector’s hands, as well as the trajectory of that variable. The euro area and Japan have bigger challenges along that second dimension.

Jose Padilla: Could be that we breach the floor. That would be manifested as a trend break in the PPP relationship posited in Figure 1.

Southern Europe cannot tolerate a high euro much longer, so either the euro falls precipitously as the european housing bubble pops and the ECB slashes interest rates (the Germans won’t like this), or else the euro pact is dissolved.

Dissolution of the euro pact need not mean a return to the old system, incidentally. There could still be a euro issued by the ECB, which would also the national currency of the Germanic countries, while the Latins would have a dual system, consisting of a euro for coins and paper money and private businesses and bank accounts, plus a national currency for government revenues and expenses. Seignorage profits would continue to be shared among all the countries, both Germanic and Latin, via the ECB. This would allow the Latin governments to inflate and devalue to their heart’s content, while still giving the private sector the advantage of a single currency to reduce transaction costs.