Some further thoughts on the bizarre behavior of the interest rate that used to be the core instrument of U.S. monetary policy.

First, a little background. The fed funds rate is the interest rate at which institutions lend their deposits held in accounts with the Federal Reserve to one another overnight. This is a market-determined interest rate which in normal times was quite sensitive to the quantity of these deposits that the Fed creates. For the last 20 years, U.S. monetary policy was primarily implemented by setting a target for the fed funds rate and changing the quantity of reserves available to the banking system so as to try to get the effective fed funds rate (a volume-weighted average of all the trades during a day) close to the desired target.

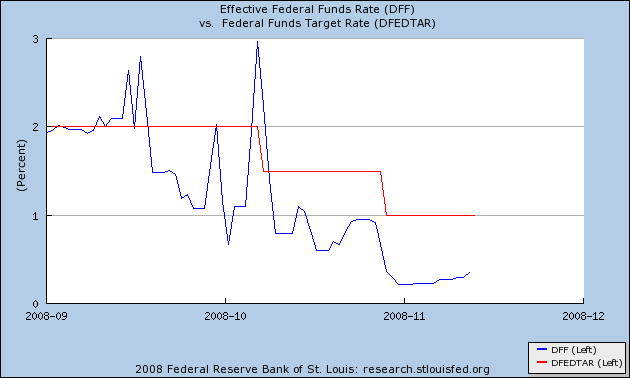

But we entered a brave new world on November 6 when the Fed began paying banks 1% interest on those deposits, the same rate as the target itself. This should have ensured that the effective fed funds rate never falls below the target. And yet the effective rate has never been above 35 basis points since the new policy of paying 100 basis points in interest on excess reserves was implemented.

|

There are two reasons why this tendency for the effective rate to come in well under the target rate is puzzling. The first is the obvious question: Why would anyone make a risky fed funds loan to another bank that only earns 0.35% when they could instead earn 1.0% at no risk by just doing nothing and letting the Fed pay them for holding excess reserves? I suggested the answer to this part of the puzzle when I first began discussing this issue:

the GSEs and some international institutions also have accounts with the Fed. But unlike regular banks, these institutions earn no interest on those reserves, so they would in principle have an incentive to lend out any unused end-of-day balances as long as they earn a positive interest rate.

So far, so good. But there’s a second part of the puzzle. If you’re a bank and there’s a GSE out there willing to lend fed funds at 0.35%, how much do you want to borrow? Let’s look at the math. If you borrow $1 billion, you pay 0.35% interest and earn 1.0% from the Fed for just holding those funds overnight, from which you’d net $6.5 million over the course of a year. If you borrow $10 billion, you’ll earn $65 million. Totally risk-free, $65 million for your bank as pure profits. Here’s the question– How much would you like to borrow?

Me, I’d like to borrow a few gazillion. And lest somebody else get to the GSEs for some of this easy action ahead of me, I’m happy to leave a standing order with my broker. I’ll pay, say, 0.5% to anybody, any time, to borrow any volume of overnight fed funds. So why wouldn’t profit-seeking behavior by banks eliminate this ridiculously easy profit opportunity?

When I first looked at this puzzle, I thought it could be explained by the guarantee fee that the FDIC assesses on any bank when it borrows. But Rebecca Wilder pointed out the flaw in this reasoning was that although the guarantee is now in effect, the banks don’t have to pay the guarantee fee until next month.

I then posed this as an open question to others. I thank the many readers who responded and particularly James Hymas of the excellent PrefBlog for summarizing the various suggestions from around the blogosphere. James ends up favoring two possible explanations. The first is that, as a bank borrows these fed funds, its total assets increase, but its equity capital remains unchanged, so that its leverage ratio deteriorates. Banks may therefore be reluctant to conduct this arbitrage, acting as if there is an internal charge of around 70 basis points assessed on every dollar of fed funds borrowed. This internal charge could play the same role in their calculations as the explicit FDIC guarantee fee discussed in my original article.

I have to say that if this is the explanation, it is profoundly disturbing to me. If banks indeed are finding themselves hamstrung to the point that they are unwilling to pick up millions of dollars that are just lying around on the sidewalk, absolutely risk-free, then how can they possibly be expected to function in their traditional role of funneling capital to legitimate investments that all necessarily entail some risk? If this is indeed what is going on, we should be looking at the spread between the effective fed funds rate and the interest rate paid on excess reserves as another indicator of a profoundly sick financial system, indicative of even deeper problems than other widely watched numbers such as the TED spread.

The second component of James’ explanation is that the GSEs themselves may be willing to lend only limited amounts to a small group of particular banks. That would give these potential borrowers some monopoly power and perhaps limited incentive to try to bid a higher rate to borrow more. There is some risk to the GSE from lending the funds to any arbitrary institution, namely the risk that the borrower will become insolvent overnight and for some reason the FDIC guarantees on those lent fed funds won’t be honored. Surely these are small risks, but they are risks nonetheless, so I can’t view the unwillingness of the GSEs to seek better terms from its borrowers with the same incredulity as I have if there’s some bank out there unwilling to borrow from the GSEs at 0.5%.

The bottom line I come away with, besides some added concerns about how deep the problems may be with the interbank lending market, is the same conclusion I offered when I originally discussed this anomaly:

the target itself has become largely irrelevant as an instrument of monetary policy, and discussions of “will the Fed cut further” and the “zero interest rate lower bound” are off the mark. There’s surely no benefit whatever to trying to achieve an even lower value for the effective fed funds rate. On the contrary, what we would really like to see at the moment is an increase in the short-term T-bill rate and traded fed funds rate, the current low rates being symptomatic of a greatly depressed economy, high risk premia, and prospect for deflation.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

economics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

credit crunch

Gee, I wish I could set up an account with the Fed. $6.5 million a year (times a few gazillion) sure beats a set of steak knives.

PS

Not only is a meaningful volume of trades is taking place well below the target rate, but the average of all such trades as measured by the Fed effective rate (brokered trades apparently) is taking place at this rate. That seems to indicate that few banks are short funds in this surplus reserve environment, and most will only put in a “stink bid” for funds, notwithstanding an apparent risk free arbitrage opportunity.

Maybe banks are gun-shy about doing any damage whatsoever to the optics of their capital ratios, even on an overnight basis.

Noticeable arbitrage activity by a particular bank may also generate the perception that it has funds to go when at the same time it is reigning in credit for customers. Perhaps this perception carries the risk of awkward customer encounters and even government backlash, along the lines of frivolous arbitrage activity being undertaken instead of getting the economy moving again with more legitimate lending activity.

And perhaps individual banks fear that the optics of more aggressive bidding within their peer group will run the risk of inciting rumours about their ability to raise funds more generally.

It is likely there is a stigma attached to having borrowed in the Fed Funds markets. Strong banks have excess reserves that earn interest from the Fed. You don’t want to explain to CEO/auditors that you borrowed Fed Funds but you don’t need it. Likewise you don’t want to show any loans on your book either, more questions you would rather avoid.

On the other hand, if you are a bank that is short of reserves, not having sufficient reserves is not an option. The strong banks won’t lend to you because they want to earn the interest from the Fed. The GSE will lend to you and try to get as much interest as possible. But you also have the alternative of selling assets (Treasury bills, the only thing that is still saleable in this market) so you don’t want to pay more than the cost of selling the T-Bill.

This suggests that the rate on 3 month T-Bills is a cap on the effective Fed Funds rate rather than the target Fed Funds rate.

There are many ‘balance sheet’ arbitrage opportunities in the market right now (i.e. arbitrage if you’re willing to grow your sheet), some of which are yielding several hundred basis points for terms of 1-2months, implying annualized ROE’s well in excess of 50% when looking at haircuts of around 3%. There are a few reasons that I have come up with would love to hear of others:

-a lack of capital in the system at that ROE

-banks’ unwillingness to tie up capital for this duration as there is reinvestment risk

-these ROEs are based of 3% haircuts which would imply an overall leverage ratio of around 33x which is well north of banks’ overall target leverage…so then you have to have more unlevered assets.

It is disturbing on the one hand, but it also means that banks are flush with opportunities provided that they have fresh capital to deploy, which most do because of TARP.

Steep yield curve is good for banks, it’s even sweeter when they can arb extremely short maturities. This problem will self-correct.

It is likely there is a stigma attached to having borrowed in the

Fed Funds markets. Strong banks have excess reserves that earn

interest from the Fed. You don’t want to explain to CEO/auditors

that you borrowed Fed Funds but you don’t need it. Likewise you

don’t want to show any loans on your book either, more

questions you would rather avoid.

Rajesh: What is there to explain? For every $100 million borrowed, an institution can make $1,780 overnight.

Professor,

This series of posts on the FFR have been some of the best you have ever posted. The FFR methodology used by the FED has always been flawed but few academic economists have taken the time to actually look at the failure. There have probably been more mini boom/bust cycles generated from this than from anything else government has done. It is just that because the actual overnight rate is so obvious now that it is hard to ignore the failure.

DickF: what is that methodological failure? I thought JDH’s discussion of failure hovers around the disconnect between the fed funds target and effective fed funds rate. He describes the failure as a break down in arbitrage. Are you thinking that there has been an absence of arbitrage in the overnight market that has been obscured previously because the target and effective fed funds rates were close?

I don’t have the energy to follow the details of this argument, but I like reading it. It confirms on of my assumptions – that Paulson has never taken the time to carefully identify what is wrong with the current financial system. He is determined to throw money at the problem. The Congress needs to refuse to provide him with any more money. He and Bernanke seems to be able to conjure money out of thin air without the permission of Congress. They have plugged holes in the dike repeatedly recently, without using any of the $700 billion. Let them continue to do so. More debt is not helping the U.S. prepare for the uncertain future.

Jim Hamilton:

What about the implications for lending? As you mentioned earlier, one effect of paying interest on excess reserves is to “sterilize” some of the liquidity injections. Isn’t this, though, just creating more incentive not to lend? Are not policy makers concerned about interbank lending and lending more broadly?

Jim,

This is indeed a still somewhat mysterious situation not fully explained by the suggestions that you present, although they help somewhat, and maybe they are it. Some of the risks perceived with these transactions may seem higher to banks than they look, at least partly due to the completely transformed environment in which generalized uncertainty seems higher.

I was at a forum in New York on Friday where I heard Perry Mehrling (among others) speak. You have basically made this point as well, but he emphasized that there has been a complete transformation of the traditional relationship between the Fed and the Treasury. It used to be that the Fed financed the Treasury. Now, with the Fed having basically sold off its Treasuries for an increasing pile of all sorts of whatnots (at the rate of $250 billion more per week), it is effectively the Treasury that is now funding the Fed.

All this fits in with the general change in the usefulness of the traditional Fed policy tools, including apparently the target fed funds rate. Which raises a question in my mind. Over the weekend I saw a report in the FT that Bernanke was contemplating a further rate cut. Why on earth, unless to catch down with the already fallen actual fed funds rate? And is it possible to have a target fed funds rate below the rate the fed is paying to depositors?

I can’t help but notice that the effective rate goes out of sync with the target rate around the same time the last investment banks on Wall Street were reclassified as bank holding companies. Could things have gone out of sync simply because of a change in culture on Wall Street–that is, could it be as simple as the fact that in reorganizing themselves as bank holding companies there is no-one out there looking to take “free money” off the table?

“The Board judged that these changes would help foster trading in the funds market at rates closer to the FOMC’s target federal funds rate.”

…you might not be the only person puzzled by all this.

“I have to say that if this is the explanation, it is profoundly disturbing to me. If banks indeed are finding themselves hamstrung to the point that they are unwilling to pick up millions of dollars that are just lying around on the sidewalk, absolutely risk-free, then how can they possibly be expected to function in their traditional role of funneling capital to legitimate investments that all necessarily entail some risk?”

..absolutely. The word I am hearing is that even 100% solid companies with no debt are unable to get capital at anything but exorbitant rates. Lines of credit are not being honored.

What the banks “say” and what they actually “do” seem to be at odds.

Perhaps this means that there is more money to be made at exorbitant rates (lack of banking competition) than a measly 0.65% overnight spread?

What do ya think? Why chase minnows when you can catch bigger fish…

JDH –

Slightly off-point, but did you see PK’s piece on deflation? The linked paper explains more lucidly than I ever could why the path between inflation and deflation is so narrow as to be almost impossible to tread (as I mentioned in an earlier posting).

sjp wrote:

DickF: what is that methodological failure? I thought JDH’s discussion of failure hovers around the disconnect between the fed funds target and effective fed funds rate. He describes the failure as a break down in arbitrage. Are you thinking that there has been an absence of arbitrage in the overnight market that has been obscured previously because the target and effective fed funds rates were close?

sjp,

A change in the FFR does not change the money supply directly. The theory is that it will allow the FED to change the money supply as banks demand at a particular rate but ever since this methodology was first begun actions by various agents in the government would either enhance that effects or sterilize the effects. Usually the FED itself would sterilize any effects. The result is unintended consequences.

The Professor has suggested a better way. Simply make changes directly to the money supply via open market transactions especially in terms of bonds.

Although it looks like free money, banks stopped doing that kind of balance sheet arbitrage in the mid 1990’s as it is a very inefficient use of bank balance sheet capacity and capital – and this applies even more so in the current environment where banks are racing to delevarage and reduce balance sheet size. The regulatory world seems capable of operating only in two modes: asleep at the switch or rabid pit bull, and right now rabid pit bull is putting it mildly. The current imperative is for global banks to deleverage from an average of 30:1 down to about 12:1 by year-end, which means exploitation of fixed income arbitrage opportunities that require balance sheet simply won’t be happening. The innovations and arbitrage relationships developed over the past 10 years have been pretty much exploded two months ago, and the market won’t be functioning efficiently for some time yet.

After our recent Keynes meets monetarism orgy we have so many different instruments out there: from Treasury, to congress, to GSEs, to FDIC, not to mention the Ben Bernanke version of FDR’s alphabet soup. Does anyone know what will actually happen to monetary value with a change in the FFR? I doubt it.

Although it looks like free money, banks stopped doing that kind of balance sheet arbitrage in the mid 1990’s as it is a very inefficient use of bank balance sheet capacity and capital…

Unless I’m missing something, it seems to me for a bank to take advantage of the gap it does not have to risk any of its own capital. You borrow from Peter to make a profit from Paul–all without tying up a dime of your own money, and all without an ounce of risk. If this then becomes an inefficient use of capital, you’d then expect the GSEs to raise their rates until interbank lending matches the Fed rate, thus closing the gap.

I hope the Fed explains the anomoly at some point. It look’s like reserves are going to increase a lot more from here:

November 17, 2008

HP-1275

Treasury Issues Debt Management Guidance on the Temporary Supplementary Financing Program

Washington – The balance in the Treasury’s Supplementary Financing Account will decrease in the coming weeks as outstanding supplementary financing program bills mature. This action is being taken to preserve flexibility in the conduct of debt management policy in meeting the government’s financing needs.

(PS. posted in Nov. 10 on accident, please delete)

I have two opinions:

In regards to 1% interest rate and the massive liquidity injection, and if I have my mechanics right, wouldn’t the establishment of the 1% interest in a way allow the Fed to subsidize banks in need. The logic goes as follows: banks convert their troubled assets which cant be sold over to the Fed, this creates excess reserves, and these reserves earn a 1% interest. Thus, without a bank doing anything, it has added a 1% return to whatever assets offered up as collateral in the Fed liquidity injections.

In regards to the effective fund rate, I think it underscores the major problem which plagues our economy and causes the Fed to plead with banks to lend: banks are committed to deleveraging. Surely banks have a large list of guaranteed investment opportunities that exceed a .25% arbitrage, but the problem is the banks arent interested. Indeed, this seems to parallel the stories of good balance sheet, solid earning companies having their credit lines cease. If banks wont accept and invest virtually free money, imagine how difficult it is to go to a bank asking for a loan.

A friend invited me to go pick up cans with him. He said it would be stupid not to, since it is free money.

I figured I could buy a mask so nobody would know it was me picking up cans. I had a clown mask picked out that had a big smile yet somehow gave you the creeps looking at it, but then I noticed it would cost several days worth of cans to purchase. By then, all the good cans would be gone.

I think Paulson should wear an evil clown mask in front of congress today. I’m a traditionalist that way.

Dear Jim, dear other readers of this blog,

I’ve never posted on any blog before, but find this question why the effective rate trades below the target rate, which should essentially be a floor rate by now very intriguing. Even more so given that even some senior economists at the Fed like David Altig don’t seem to know the answer. (see the comments on http://macroblog.typepad.com/macroblog/2008/11/the-changing-op.html)

Here’s an explanation given by Dan Thornton of the St.Louis-Fed way back in September 2007 or so. He argues that Fedfunds and 3M TBills are very good subsitutes – presumably even better during liquidity trap times. Thus, arbitrage might dictate the effective fedfunds rate trades at par with the 3M TBill rate – which it in fact has over the last couple of weeks.

Here’s Dan’s argument in brief:

“T-bills and federal funds are very good substitutes for meeting the liquidity needs of depository institutions. Hence, one possibility is that the flight to quality pulled the funds rate down from the FOMC’s target.”

from a St. Louis Monetary Trends cover page by Dan Thornton. Here’s the link:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/mt/20071001/cover.pdf

Many thanks for reading my comment and I would be happy to hear your views on this argument.

Best wishes,

Sebastian Watzka

I thought you might be interested in looking at the federal fund rate and federal fund target rate interactive charts in http://fxeconostats.com. Historical data is available as well.

I think what’s confusing you is that you are focusing on banks’ supply of funds at the federal funds rate (FFR). I suspect that what is constraining the price is the demand for funds at any rate above the FFR. Banks may have so much liquidity that they are now suppliers of funds — the effect of the interest on reserves/quantitative easing policy. The GSEs are thus the demand side of the market — and as Thornton/Watzka above pointed out they are arbitraging between the rates they get on their notes and the FFR.

Thus, if it’s the GSEs that are borrowing, there’s no reason for them to borrow at a FFR above the rate at which they can get short term funds on the market. In other words, the short-term agency rate is a cap on the FFR.

I suspect the tbill rate may be acting as a ceiling, not a floor, on the fed funds rate!

Ordinarily, the fed funds rate is above the tbill rate because of the risk of a bank failing to repay. But there is a risk with tbills too: if you buy a 3 month bill, and it plummets the next day (yield increases), then you could be waiting up to 3 months to get your money back. But it appears that the 1% interest from the Fed is collected within 2 weeks at most. I can’t really tell which is the safer investment. Maybe the tbill rate is the ceiling, not the floor, on fed funds!

This yield curve from the Treasury seems to confirm the massive demand for tbills maturing soon. Today, it was 0.06% on 1-month tbills.

Does anyone know if all the excess reserves are making their way, via lending, to institutions that are entitled to the 1%? Could this answer be hidden in the Fed’s accounts covering these interest payments? Presumably, the answer is Yes, but we could narrow down the hypotheses if this was confirmed or rejected. If some excess reserves are failing to earn interest, this would imply that the holder (the GSEs) are so scared of default that they may be rejecting higher offers.

Sebastian Watzka: When Thornton’s piece was written, there was no interest being paid on excess reserves. It’s the effect of that interest rate that is the source of the puzzle.

ccm: You’ve missed the boat entirely. I’m talking about the demand for fed funds, that is, the borrowing side. The observation is that, when a bank earns interest on excess reserves and can borrow at a rate that is less than that earned on excess reserves, it should want to borrow fed funds and simply hold the funds borrowed in its account with the Fed as excess reserves. Just because a bank has excess reserves doesn’t make it a “supplier of funds” in the current regime– that’s the whole point!

Has anybody asked a banker why this anomaly exists?

JDH,

Bernanke acknowledged the problem specifically in Q&A this morning, responding to a question as to whether the Fed’s extraordinary asset activities had complicated monetary policy implementation. He identified the differential without elaborating on what they were going to do about it.

It was nice of Macroblog to acknowledge your question, although the response wasn’t exactly robust.

It sure sounds like something they didn’t expect.

JDH,

I don’t think my first post was clear. I think the appropriate framework for the problem is more akin to a bilateral monopoly pricing problem than a market situation.

I suspect that the GSEs have a standing order with their brokers that they are willing to borrow at a rate comparable to market short-term lending rates. Thus banks can lend at this rate — though it obviously isn’t in their interest to do so.

Presumably there’s a small quantity of non-bank funds that get allocated every day. Isn’t it possible that banks are saving money by closing down their FF market operations? (Kind of like the way I stop putting time into keeping a daily tab on my checkbook when I know the account is way above the minimum.)

I am sorry that my original comment was confusing. When I stated that banks were “suppliers of funds”, I simply meant that they are collecting interest on their excess reserves from the Fed — a point with which I think you agree.

great post. very puzzeling so i asked a trader i know that deal with the fed. his take is that since banks / corp / GSEs or anyone with account at the fed does not want to lend cash to anyone else, they lend to “clearing banks.” only the reserves from the clearing banks earn the interest paid by the fed. therefore, these clearing banks take in the reserves at a rate lower than the interest rate paid by the fed from these non-clearing accounts and earn the spread by earning the interest paid by the fed. so effective fed funds rate trades below interest that fed pays. an easy arb opportunity if you are one of the clearing banks. but as a result of this, fed’s reserves now stand at well over $1tril versus $7bil which is normal level. not a good sign that only place people trust enough to lend to is to the fed.

Anon 2:02’s post is interesting.

It sounds like the clearing banks are borrowing on the FF market, but they are not competing with each other. Thus, the rate at which the GSE’s are willing to borrow (since they’re another party capable of absorbing huge quantities of funds) is the borrowing rate below which the clearing bank coalition can not push the FFR.

I hope someday somebody lets us know which of the many theories is correct!

Interesting stuff, but Jim, you should take a look at the 30 year swap spread situation. On 11/13, they went negative, and have gone further negative to -23 basis points today, 11/18. This was once thought to be impossible, and no “rational investor” would do this. The negative spread means that many large investors looking for default insurance think that they have a better chance of collecting insurance from a private company than from the US government, in the case of default on US 30 year bonds. If this situation continues, it seems to have a large potential impact on banks, insurance companies, the Fed, the US economy, and international trade.

Your views, and those of the group would be interesting.

It doesn’t sound like any of you actually read the press release from the Fed on Oct. 6 regarding paying interest on reserves. Yes they are paying interest on excess reserves and no the interest on required reserves is not 1%. Here’s two paragraphs that should help with this discussion:

The interest rate paid on required reserve balances will be the average targeted federal funds rate established by the Federal Open Market Committee over each reserve maintenance period less 10 basis points. Paying interest on required reserve balances should essentially eliminate the opportunity cost of holding required reserves, promoting efficiency in the banking sector.

The rate paid on excess balances will be set initially as the lowest targeted federal funds rate for each reserve maintenance period less 75 basis points. Paying interest on excess balances should help to establish a lower bound on the federal funds rate. The formula for the interest rate on excess balances may be adjusted subsequently in light of experience and evolving market conditions. The payment of interest on excess reserves will permit the Federal Reserve to expand its balance sheet as necessary to provide the liquidity necessary to support financial stability while implementing the monetary policy that is appropriate in light of the System?s macroeconomic objectives of maximum employment and price stability.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/20081006a.htm

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=abYTR9BqGlBo&refer=home

“The Fed’s failure to meet its target risks pricing billions of dollars in short-term debt at interest rates lower than the Federal Open Market Committee intends. It also makes it harder for traders to bet on the central bank’s future course of monetary policy.”

11:29 p.m. above – get yourself updated

I’m with Readthepress. . . on this one. There are two important points which have been largely neglected in the above discussion:

Readthepressrelease: We have carefully read and discussed in detail here at Econbrowser not only the October 6 Fed press release you mention, but also the October 22 amendment from the Fed raising the interest rate paid on excess reserves to within 35 basis points of the target (which Econbrowser discussed on October 25), as well as the November 6 decision by the Fed to raise the interest paid to 1.0%, the same as the target. That is the point of the current post to which you contribute your comment.

http://economistsview.typepad.com/economistsview/2008/11/deflation-quant.html#more

…

“I, along with really smart economists like James Hamilton, have fought to explain this phenomenon. But perhaps it cannot be explained because we don’t have all of the information!

…

Has the Fed moved toward a money growth target, rather than an interest rate target? William Poole,former President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accuses the Fed of not being transparent and shifting monetary policy without announcement. Although he does not speculate as to what the new policy is, he does state that by not announcing its new policy, the Fed is breaking the law.

According to Poole: “Something is happening at the Fed that has not been announced.””

From the Oct 28-29 FOMC minutes:

“In the discussion of System open market operations over the period, it was noted that reserve management had become more complex as a result of the large provision of reserves associated with the recent expansion of the Federal Reserve’s liquidity facilities; in particular, the effective federal funds rate had been persistently below the FOMC’s target. While the payment of interest on reserves seemed to be helpful in mitigating downward pressure on the funds rate, a number of institutions evidently were willing to sell funds at interest rates below that paid on excess reserve balances. Anecdotal reports suggested that this was particularly the case for those institutions that are not eligible to receive interest on the balances they maintain at the Federal Reserve. Going forward, however, the interest rate on

excess reserve balances could be adjusted, and it might establish a more effective floor on the federal funds rate over time as more depository institutions revise their strategies in the federal funds market in light of the payment of interest on reserves.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/monetary/fomcminutes20081029.pdf

If they will only pay 0.3% and the FDIC insurance fee does not have to be paid yet, this implies there will be no borrowing once it has to be paid.

Or am I missing something?

FDIC Approves Final Rule

“Short-term debt (30 days or less) has been eliminated from the debt guarantee program”

Is it possible that the GSEs and other international institutions are unwilling to lend to banks that do earn interest on their reserves? In other words, does the rate just reflect borrowing and lending for those unaffected by the minimum rate?

Perhaps these institutions distrust banks enough to think they might fail overnight, despite their huge reserve balances? This may make no sense. I’m grasping here.

One would think that quantitative easing would eventually improve balance sheets enough that banks would start lending again.

JKH writes:

“Has the Fed moved toward a money growth target, rather than an interest rate target? William Poole,former President of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, accuses the Fed of not being transparent and shifting monetary policy without announcement. Although he does not speculate as to what the new policy is, he does state that by not announcing its new policy, the Fed is breaking the law.”

Yes, the fed is now expanding the monetary base rapidly, and paying interest on reserves is helping to facilitate this. See:

http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate/2008/11/14/quantitative-easing-has-begun/

It has a link to a Fed article that explains the thinking on this policy before they implemented it.

I worry however that this may some time to be effective. Banks may just take their 1% and hoard the reserves until the long run when we’re all dead.

The St. Louis Fed weighs in on how the renumeration rate doesn’t act as a floor for the Fed funds rate.

Why don’t other central banks just do this:

http://www.rba.gov.au/MarketOperations/Domestic/open_market_operations.html

You blokes couldn’t organise a chook raffle.

Problem (partially) solved?

The Board believes that the disparity between the actual federal funds rate and the rate paid by Reserve Banks on excess balances may partly be caused by the leverage incentives imposed on correspondent institutions to sell excess balances into the federal funds market rather than maintaining those balances in an account at a Reserve Bank.