Having coauthored an entire book on the financial crisis of 2008 (Lost Decades, with Jeffry Frieden) I think that one of the most important qualities for a policymaker is the ability to look forward, and assess potential dangers and understand why those dangers arise. Looking back to 2007, it’s of interest to see who foresaw the impact of adverse feedback loops in the financial system as risk was repriced.

While the problems with subprime mortgages have understandably received a lot of attention, it is important to remember that the whole subprime market itself is only a relatively small part—10 to 15 percent, depending on the exact definition—of the overall mortgage market. How, then, could problems in this relatively small market infect so much of the financial sector, and possibly real economic activity? The answer appears to lie in the characteristics of some of the complex financial instruments that have been developed as a means to diversify and spread risk. These instruments include not only mortgage-backed securities, including subprime mortgages, but also CDOs—collateralized debt obligations that package bonds, including mortgage-backed securities—and CLOs—collateralized loan obligations that package business loans—and a variety of associated derivatives, such as credit default swaps and indices based on such swaps. These instruments are obviously very complex, which makes them difficult to understand and evaluate, not only for the average investor, but even for sophisticated investors. In particular, it is difficult to determine the risk embedded in these instruments and how to price them.

Investors have relied on a variety of means to assess their exposure to them—from high-powered mathematical models to agencies that assign ratings to them. But models are, at best, approximations, and, because these instruments are relatively new, there were not necessarily enough data available to estimate how they would do under the stress of a downturn in housing prices or economic activity. As for the rating agencies, once recent developments began to break, they quickly began announcing sharp downgrades, which intensified awareness of the uncertainty surrounding the risk characteristics of many of these instruments.

As delinquencies have risen in the subprime market, the complex instruments associated with those mortgages have come under question. Moreover, questions have arisen concerning the underwriting standards used by financial firms that received fees to originate and package mortgages for sale rather than holding them for their own account. In consequence, holders of these securities, many highly leveraged, have been forced to sell into illiquid markets, realizing prices that are substantially below their model-based estimates, or to sell liquid assets as an alternative. Significant losses have been realized in the process.

Once other investors saw how quickly and unpredictably such markets could cease to function well, those who used similar complex instruments likely grew concerned about how quickly and unpredictably their own exposures might change for the worse, leading them to pull back, too. One might say that these developments bring us back to Latin 101 and the root of the word “credit.” The root is “credo,” which means “I believe” or “I trust”—that is, investors’ belief was shaken, both in the information they had on the degree of risk these instruments embodied and in the price they were going for, and they are pulling back from these markets, presumably until they understand these instruments well enough to restore that belief.

Even with corrections to credit underwriting standards, it still may turn out that these innovations don’t actually spread risk as transparently or effectively as once thought, and this would mean—to some extent—a more or less permanent reduction of credit flowing to risky borrowers and long-lasting shifts in patterns of financial intermediation. It also could mean an increase in risk premiums throughout the economy that persists even after this turbulent period has passed. In a speech I gave a few months ago, I focused on the phenomenon of low risk premiums in interest rates throughout the world.2 In fact, there was considerable debate about what might be causing the very low price for taking on risk. What we are seeing now could be the beginning of a return to more normal risk pricing. As such, this development would not be disturbing for the long run. However, as we are seeing, the transition from one regime to the other can be quite painful.

That’s from a speech in 2007, by then Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President Janet Yellen to the National Association of Business Economics (NABE). Keeping in mind how carefully one must tread as a public official (as opposed to someone pontificating on a blog), these comments strike me as quite prescient, and with the benefit of hindsight, correct in diagnosis.

See also Jim’s post on Yellen’s presentation at the UCSD Economics Roundtable in July 2008.

Update, 7/27, 8AM Pacific: Stephen Williamson writes:

If we stick to economic ideas, Yellen and Summers are quite similar. Both are Old Keynesians – they’re aware of mainstream macroeconomics, but seem most comfortable with an IS-LM, Phillips-curve view of the world.

This strikes me as an odd comment. In fact, teaching macro back in the mid-1990’s, I recall assigning papers from both Yellen and Summers (and Mankiw and Blanchard and Hubbard…). The Yellen papers included “A Near-Rational Model of the Business Cycle, with Wage and Price Inertia,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, and “Can Small Deviations from Rationality Make Significant differences to Economic Equilibria?” American Economic Review (both with Akerlof), and “Efficiency Wage Models of Unemployment,” American Economic Review P&P. The first and third papers were reprinted in a book called New Keynesian Macroeconomics (edited by Mankiw and Romer). So, it’s not that Yellen is just “aware” of current mainstream macroeconomics, she was part of the leading edge of research that has led to development of NK DSGEs. Just a clarification.

Full disclosure: I did my graduate work at U.C. Berkeley, where Janet Yellen and her husband George Akerlof were professors. I took graduate macro from Professor Akerlof (as previously noted here, here, here, and here). (8/5/13)

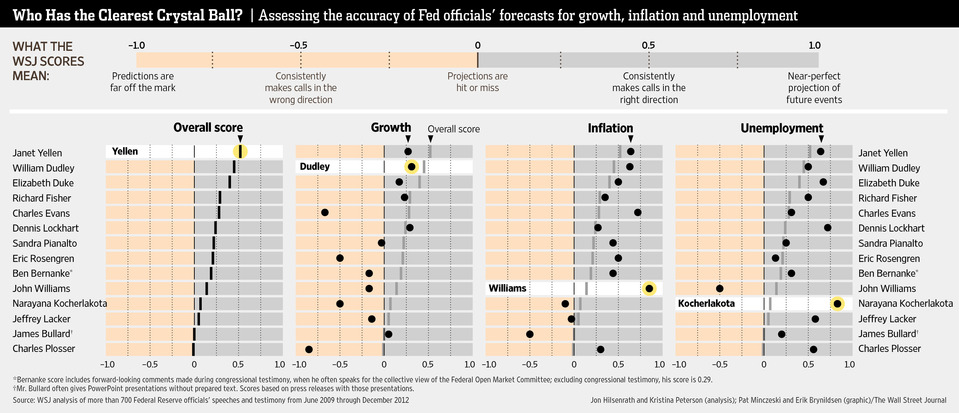

Update, 7/29, 11:30AM Pacific: The Wall Street Journal today published “Federal Reserve ‘Doves’ Beat ‘Hawks’ in Economic Prognosticating: Slow Growth, Low Inflation Give Yellen, Dudley Upper Hand on Forecasts”. The accompanying graphic is highly informative:

Source: WSJ.

In the Yellen camp, eh?

I personally find all the kibitzing about the new Fed chair interesting. Krugman, Sumner, Cowen, now you. Intriguing. Is this how popes are elected in the internet age?

I am personally of the view that the head of the Fed should be boring, or at least give the impression of being boring. So for me, it’s Yellen.

It’s ironic that the Fed doctors practice homeopathic medicine, actively and openly suppressing risk pricing.

One big difference though is that back in 2007 the risk curve was actually sloping downwards! At least now it slopes up, with riskier assets priced to receive higher expected returns.

Of course, Meredith Whitney’s comments about financial institutions were quite prescient, and she has been warning about state and local government finances for a while. She just commented on Detroit’s bankruptcy:

Detroit aftershocks will be staggering

Leaders across the country cannot continue as they have, says Meredith Whitney

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/34abcabc-f389-11e2-942f-00144feabdc0.html#comment-4983902

Menzie,

The explanation for the run up in CDS and index CDS prices during the financial crisis depends on the assertion that they are “obviously very complex, which makes them difficult to understand and evaluate, not only for the average investor, but even for sophisticated investors. In particular, it is difficult to determine the risk embedded in these instruments and how to price them.” The uncertainty inherent in subprime, CDOs, etc. pricing allegedly spread to these supposedly similarly complex products.

On the contrary, CDS and CDS index pricing is relatively straightforward, unlike the CDOs. So this complexity contagion argument can’t be right.

Steven: “I am personally of the view that the head of the Fed should be boring, or at least give the impression of being boring.”

Steven, I’m with ya, man. How’s the following for boring? The Rip Van Winkle Fed Chairman/Chairwoman/Chairperson:

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_–YjWiyF8eE/TJzdQUBzQqI/AAAAAAAAHR4/Zv2iTGOJr6g/s400/Larry+Summers+is+sleepy+three-thumb-480×350.jpg

Now if we could just ensure that he stays in this general condition for his term(s).

I’m sure by now some clever Ph.D. types, employed by the TBTE banks that own the Fed, have designed “low-frequency trading” software to manage secondary market MBS, agency, and Treasury securites that would allow the Fed Chairman to enjoy long, luxurious naps while presiding over acilitating the TBTE banks’ mischief and license to steal; or, better yet, permanent retirement.

Jeffrey: “At the root of the problem is the incentive system that elected officials used to face. For decades, across the US, local leaders ran up tabs for future taxpayers; they promised pensions and other benefits for public employees that have strong legal protection. That has been a great source of patronage for elected officials: they can promise all sorts of future perks to loyal supporters (state and local workers) with very little accountability on the delivery of those promises.

Today, we are left with the legacies of this waste. The bill for promises past is now so large for some cities and towns that it is crowding out money for the most basic of services – in the case of Detroit, it could not even afford to run its traffic lights. Across many American cities, cuts to basic social services have already been so deep that they have made the communities unpleasant places.”

Indeed. The tragic, untold story of Anglo-American oil empire is that the US built an economy, society, and political system from the 1920s to the 1970s on the basis of 4-5%/year crude oil production (3-4% per capita, which is a compounding doubling time of 20-25 years), 6-7% debt-money supply, nominal GDP, and wage growth that peaked in 1970-85, whereas crude oil production per capita has decline since by 50% and real wages for the bottom 90% are where they were 40-45 years ago.

Name a civilization in history that experienced a 50% decline per capita in production/supply of its primary energy source that did not decline and eventually collapse.

Since the 1970s-80s, the US has increasingly become an excessively indebted (to wages and GDP), militarized, deindustrialized, financialized, and feminized society with a Third World-like wealth and income concentration.

Now the world is where the US was in the 1970s WRT crude oil production and oil exports per capita, suggesting that world industrialization has peaked along with real GDP per capita. China-Asia will no longer contribute to increasing growth of world real GDP per capita.

Promises by gov’ts for perpetual growth of debt-money supply, resource extraction, investment, profits, production, employment, and wages at a discount rate to promises of 6-7% cannot be met in a world of 0-2% trend nominal GDP and 0% to negative real GDP per capita.

Peak Oil and the “Limits to Growth” (LTG) have arrived. Growth of real GDP per capita is no longer possible hereafter. There is no economic textbook theory or school of thought to address a once-in-history contraction of population, resource consumption per capita, and real GDP per capita, i.e., end of capitalism, on a finite, spherical planet or aboard “Spaceship Earth”.

Hereafter, accelerating automation of paid labor worldwide in the next 5-10 to 30 years, particularly in the service sector, via evolving technological advances in robotics, smart systems, biometrics, bioinformatics, nano-electronics, and quantum computing, risks exacerbating the drag effects of demographics, Peak Oil, population overshoot, and increasingly acute effects from loss of arable land, deforestation, and drawdown of aquifers.

Risks of default on these instruments was eliminated (so they thought) by buying insurance against default from AIG and others.

Nobody knew the total of insurance bought from an individual insurance company (such as AIG) because the Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000 explicitly forbid government agencies from collecting information about these private contracts. This lack of information was a major part of the reason that Paulson and Bernanke panicked. They had a problem of unknown size and unknown character.

Abstract understanding of causal interdependencies (as exhibited by Yellen) is essential but data is also essential.

I don’t think Yellen or anyone else really understood the problem in 2007.

Rick Stryker: If the CDS is on a CDO, and the CDO is difficult to price, then how is the pricing of the CDS easy (that is, if one wants to “correctly” price).

I have also wondered if there were ever CDSs ever written on synthetic CDOs, which would strike me as pretty hard to price as well.

Menzie,

I don’t think Yellen was talking about CDS on CDOs, which are just synthetic CDOs.

She referred in her speech to the run up in CDS spreads, and indeed, by early September 2007, the CDX on-the-run 5-year index had doubled since June of that year. Her explanation seems to be that the uncertainty in the pricing of subprime and CDOS (cash or synthetic I assume) had spilled over into CDS and credit indices.

CDS and indices had indeed risen very significantly over that summer. But that’s not because of uncertainties about pricing. Plain vanilla CDS and indices are basically priced consistently with bond spreads. CDS and index spreads were just following the run up in bond spreads.

Subprime and mortgages on the other hand have a lot of uncertainty and complexities. CDOs are correlation products and you have the problem of modeling the joint default behavior of the underlying instruments, usually done using some sort of copula such as the Gaussian.

One example of a CDS on a synthetic CDO was the CDO^2, a synthetic CDO whose underlying assets were tranches of synthetic CDOS. You might consider the forward starting synthetic CDO and options on synthetic CDOs to perhaps be further examples.

It’s Janet, who told you, Menzie ?

She will clean this mess up, while Ben will surf at Kauai beach.

Bill, this clever fox, is also “all praise” for Janet :

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2013/07/comments-on-janet-yellen-thursday.html

Cleaning housewife, here she comes.

Next Fed Chairman

Quite a few got the crisis right in advance, including an accurate notion of its potential severity. Percentage-wise, though, maybe only 5% of forecasting economists, hedge fund managers, and others whose job it is to foresee such things were calling for even a mild recession. Yellen was certainly not one of them. Here from her Dec 3, 2007 speech in Seattle: “To sum up the story on the outlook for real GDP growth, my own view is that, under appropriate monetary policy, the economy is still likely to achieve a relatively smooth adjustment path, with real GDP growth gradually returning to its roughly 2½ percent trend over the next year or so, and the unemployment rate rising only very gradually to just above its 4¾ percent sustainable level.” Already in financial markets it was as though a bargeful of fireworks had all been set off accidently, with rockets and smoke and sparks flying everywhere. Remember Secretary Paulson’s stillborn concept of a SuperSIV? On the day of Yellen’s speech, the fed funds rate was still 4.5%. Indelible proof of the Fed’s cluelessness about the catastrophe already underway.

The next Fed Chairman ought to be someone who understands markets and sound money, like William McChesney Martin. And who saw the main event coming. Neither Yellen nor Summers is that person.

September 10, 2007 is NOT prescient. It is more in the vein of “after the horses have fled”

Question is – now that junk bond yields were recently at new record lows, what is she saying now? Nothing. she is a super dove. always looking to press down on rates with new excuses to do so. She will keep rates at zero for five to seven more years, trying to correct inequality as an excuse. that is my prediction.

Is it too soon to start the “JDH” to replace Bernanke rumor?

Bruce,

Just one small clarification. I may have screwed up on the formatting, but in any case the entire text after the Ft.com link was a quote from Meredith Whitney’s column.

Here is my 2¢ worth:

The GELM (Government Export Land Model*)

Let’s think of local and state (provincial), and for that matter, national governments as being similar to oil exporting countries, in that they consume a percentage of tax revenues and net debt infusions, in order to pay current benefits to employees and operating expenses and to pay current and future retirement/health benefits.

And let’s just really focus on current and future retirement benefits.

As Michael Lewis noted in his recent book, “Boomerang,” a lot of local governments, especially in California, are on track to consist of little more than a small staff that collects taxes and forwards virtually all tax revenue to retirees. And of course, most public pension systems are assuming a (highly unrealistic) estimate of 7% to 8% on future annual returns. Of course, the lower the actual investment return, the larger the unfunded pension obligation.

In any case, if we assume flat to declining tax revenue, combined with rising retirement obligations (especially as investment returns continue to disappoint), it seems to me that the net result would be an accelerating rate of decline in services provided to the taxpayers, perhaps even as governments try (probably) unsuccessfully to materially raise tax revenue, by raising tax rates.

From an Amazon review of “Boomerang”

*For the oil exporter model, you can search for: ASPO + Export Capacity Index, but it can be summarized as follows: Given an ongoing oil production decline in an oil exporting country, unless they cut their oil consumption at the same rate as the rate of decline in production, or at a faster rate, the resulting net export decline rate will exceed the production decline rate, and the net export decline rate will accelerate with time.

Prescience is generally defined as foreknowledge or foresight. Yellen’s observations are about what happened in the past. She gives no reason for the creation of these complicated instruments and she gives no solution. Perhaps as Menzie notes she is being careful because of the sensitivity of her position, but I do not see much in her comments that give solutions. Most of these complicated instruments were the unintended consequences of thoughtless government regulation.

There have been plenty of posts by various people, such as McBride at Calculated Risk, noting various times when Yellen exhibited greater prescience than anybody else at the Fed about “the main event,” along with some others. She is very knowledgeable and highly qualified, and also the originator of what is now the global norm of a 2% per year annual inflation target.

BTW, it does not hurt that she is married to George Akerlof, a very sharp observer of the macroeconomy.

Correction to my last post : Now it seems, according to the latest hint from a very knowageable person, that Bernie Madoff will be freed, given an award and will be the next FED chairman (instead of Yellen).

Yes, well, would fit too.

Update added at end of post, 7/27 8AM Pacific.

The use of “dove” v “hawk” is very strange when it comes to monetary policy. It seems that a “dove” is someone who is likely to take an aggressive position on monetary expansion and low interest rates while a “hawk” is someone who is more inclined to support passive wait-and-see policies. Once again it appears that the progressives have appropriated the language to distort the actual autocratice, aggressive approach while painting their opposition supporting freedom as aggressive. We live in a strange world.