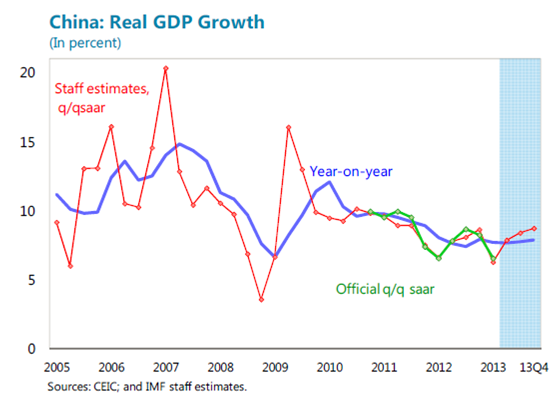

It’s an understatement to say there has been a lot of dismay at the drop in Chinese year-on-year GDP growth, from 7.7% to 7.5%. Figure 1 below, from the IMF’s Article IV report released on July 17, shows data only through 2013Q1, although the forecast for 2013Q2 looks about right to me.

Figure , from IMF Article IV Report on China.

The blue line year-on-year number for 2013Q2 appears about right (and hence the staff forecast for q/q growth as well, although I can’t find a 2012Q2 q/q estimate on the National Bureau of Statistics website; Roubini says NBS reports 1.7% q/q SA, vs. 1.6% in Q1).

I think it’s useful to consider the IMF’s assessment before predicting a wholesale collapse in growth.

Despite weak and uncertain global conditions, the economy is expected to grow by around 7.75 percent this year. Although first-quarter GDP data were sluggish, the pace of the economy should pick up moderately in the second half of the year, as the lagged impact of recent strong growth in total social financing (a broad measure of credit) takes hold and in line with a projected mild recovery in the global economy. High-frequency indicators have been mixed recently, with infrastructure spending and retail sales showing more resilience than exports and private nonresidential investment . … Overall, the risks to the near-term outlook have moved more to the downside, as the expected rebound in the second half of the year may not materialize if, for example, external demand for China’s exports remains subdued and/or the weaker activity in recent months spills over into investment and consumer demand going forward. On the upside, credit growth has traditionally been a leading indicator of economic activity, which has also typically seen an upswing following a leadership transition as new local officials ramp up investment spending.

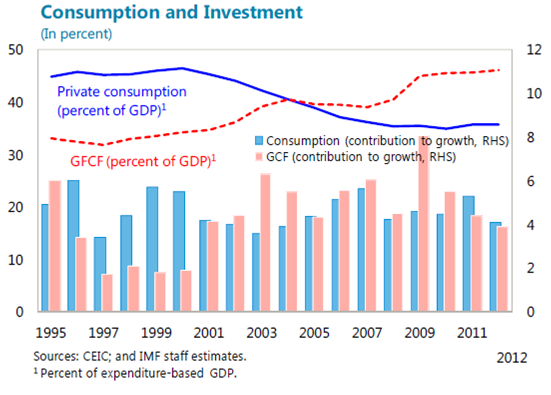

What is important to keep in mind as one considers slower growth is that this has been a long time in coming. The [up to now rhetorical] stress has been on more quality growth, where quality growth means sustainable. In addition, it requires a decreased dependence on fixed investment, which accounts for a very high proportion of GDP — around a half. The incremental contributions to GDP growth are important in this respect.

Figure from IMF Article IV Report on China.

It’s essential for private consumption to rise as a share GDP, reversing the trend in place from 2001 to 2010. This is a recurring theme in Econbrowser [1] [2] (although of course hardly original – see here and here, for instance; contra here). Otherwise, the rebalancing that has taken place with respect to the external accounts is likely to dissipate.[3]

It’s in this context that one has to understand the recent liberalization of the deposit floor. This in itself has little effect; however to the extent it signals an imminent liberalization of deposit rate ceilings, we might soon see actual moves to ending the financial repression that has limited interest income to households and hence slowed consumption. [4] A more explicit and comprehensive linkage between financial reform and domestic rebalancing away from investment to consumption is provided by Nick Lardy (shorter here).

The question is whether Chinese policymakers can keep their nerves as more news comes in. [5]. It seems the leadership is attempting to assuage anxieties by committing to a growth floor of 7% (7.5% is the target for 2013) [6].

By the way, none of this is to deny the clear hazards entailed in the process of liberalization, necessary as it is. Financial liberalization – in developing and advanced countries alike – can go terribly wrong, but that is not a reason to stop. As Jun Ma and Michael Spencer note (“Addressing the China Bears,” DB Global Economic Perspsectives [not online]:

… finance has become more complex in recent years, in ways that echo developments in developed market economies prior to 2008. Wealth management products are deposit substitutes created to circumvent restrictions on deposit rates. The funds so raised are invested in assets that are not simply loans, but may be portfolios of loans, or bonds, or properties or other instruments. The lack of transparency is troubling. The likelihood that intermediaries hold less capital against these assets and almost certainly less liquidity makes the system inherently less stable. By all appearances, the large banks that dominate the financial system are much less exposed and the risks may be concentrated in very small, systemically less important institutions.

But as with the [Global Financial Crisis], complexity of finance itself is a source of risk. [Wealth Management Products] in China look like ‘mini-bonds’ in Hong Kong – retail instruments that are inherently riskier than deposits but sold to investors who may not appreciate the difference. ‘Informal securitization’ is an oxymoron but much of the ‘off-balance sheet’ activity appears to be just that. What is needed is regulation, supervision and transparency. …

The longer interest rate liberalization is put off, the harder it will to manage a successful move to a more price-oriented financial market.

The entire Article IV report is required reading, if only because of all the statistics reported in the document. Also, more from The Economist.

What I struggle to understand is how interest rate liberalization is often portrayed as a precursor to capital account liberalization. If rates go up, this is going to put more upwards momentum on the currency, at a time when (some) people believe that the REER is already overvalued, and in a world in which net exports has recently been a drag on growth. How would you evaluate this tradeoff?

there is a problem with your RSS feed. Try to click on it at the bottom of your blog.

This belief in the magical power of floating deposit rates to fix everything is going to end badly for china. If floating rate deposit interest rates are such a panacea, why haven’t WMPs helped the economy rebalance more? In terms of macro rebalancing the fact that WMPs are not transparent is not relevant.

China’s economic problems are political economy problems stemming from local – central funding conflicts which leads to an over reliance on land sales for local governments and incentives for local governments to promote investment. Liberalizing deposit interest rates does nothing to address this issue.

What I struggle to understand is how interest rate liberalization is often portrayed as a precursor to capital account liberalization.

It’s political, not economic. These are the expected reforms of the mid-2000s that were blocked by an internal power struggle. Reform is now back on track.

Menzie, you are missing the broader point. The reason Investment/GDP is so high and Consumption/GDP is so low is because of the financial repression you cite. Real interest rates have been negative for 30 years in China, thus the interest rate liberalization process almost certainly means HIGHER real interest rates going forward which implies MUCH weaker growth. It seems very unlikely that consumption can pick up the slack quickly enough to avoid a major overall growth slowdown

The q/q figures are in the press release, with some major revisions to the 2012 series in the 2nd footnote:

http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/pressrelease/t20130715_402910992.htm

Two questions =

1. In the IMF quote: “On the upside, credit growth has traditionally been a leading indicator of economic activity…” how do they define “credit growth?” If this a euphemism for monetary expansion?

2. Menzie, when you write: “The longer interest rate liberalization is put off…” what do you mean by “interest rate liberalization?” Do you mean the government reducing the interest rates it charges for RMB?

pluto at July 23, 2013 10:45 PM: We had a problem earlier that we think we’ve now fixed. Do you still have a problem? I get the correct feed when I click on either “RSS feed” or “subscribe in a reader”.

How credible are Chinese GDP figures?

Gordon Chang (Forbes columnist and China expert) and Amrita Sen (Energy Aspects, formerly Barclays) were of the view that Chinese electricity consumption in Q1 and into Q2 reflected GDP growth more in the 3-4% range, and oil consumption figures also supported this view.

Meanwhile, a number of other organizations and i-banks rather passively accepted official Chinese data.

How do you reconcile electricity data with reported Chinese GDP?

RN: I think you have to look long term at the development of a financial system that allocates on the basis of returns. Also, when capital controls are relaxed, one would want to consider the possibility of net outflows; higher deposit rates would stem such outflows.

A H: There are many, many, many distortions in the Chinese economy. Financial system reform is one of the required actions, not the only.

bafmacro: Once again, there’s a short term/long term distinction. In the short term there may be some lost output; in the long term, liberalization if done right could enhance the workings of the financial system. In addition, since the household sector is a net saver, higher interest rates on deposits might lead to higher consumption.

Ricardo: Credit growth is lending (domestic credit formation). Money supply is sum of currency and checking deposits (and time deposits if broad).

By liberalization, one aspect is the removal of caps on the rates the banks can pay on deposits (I think that’s pretty clearly laid out in the text of the post, as well as the Article IV report).

Steven Kopits: With the growth of the tertiary sector, I downweight the electricity series (I used to use it myself). As an ad hoc alternative, one can look at the Li Keqiang indicators — electricity, rail, and lending; a graph is provided here.

Thanks for this, Menzie.

I don’t know. China looks a mixed bag to me, and many of the indices have heavy reliance on the National Bureau of Statistics, and I am not quite sure which of their series I can consider un-massaged.

But it’s definitely a good data source–thanks for the link.

The China Sales Managers Index gives you a whole economy view of what is really happening, not just manufacturing like other indices like to track. It’s monthly and measures the speed and direction. It’s completely independent and run by a private economics research firm by people who have a lot of experience.

China will grow faster this year than ever in its (or any nation’s) history: it will add $690 billion to its GDP. Next year it will grow even faster.

Talk about rates of increase is misleading and silly. Even irrelevant.

When the reality of China’s growth is clear this nonsense will either be forgotten or the true growth figures will be questioned because they don’t agree with the “slowdown” story.

China’s statistics are as good as Canada’s according to Mark Mobius, who has billions riding on his assessment of them. They’ve proven to be conservative for the past 40 years despite The Economist’s 56 predictions of ‘hard landings’.

I’m beginning to think that this nonsense is coordinated Western propaganda, in response to the fact that the Chinese government is the best manager of a national economy the world has ever seen.

Thanks Menzie. Got it. I miss read the comment by the IMF. After reading your response I saw my mistake.

I also misunderstood your comment on liberalization meaning reducing the ceiling on interest rates. The term liberalization is used in many contexts. I understand you point and it is well taken. Liberalization of any governmental constraints on markets is always positive. This would be a good lesson for our congress to learn.

*dials the local church*

“Pastor, has hell frozen over?”

“No, my son, why?”

“Menzie and Ricardo agreed on something!”

Anonymous: Not too quick. Piecemeal liberalization might make the situation worse. For instance, liberalizing the capital account before the domestic financial system is liberalized (with plenty of prudential regulation) might make matters worse. So, not quite full agreement.

It would be a great time to do an economics primer on China: “Understanding the Chinese Economy” or something to that effect.

A lot of people in our industry are mulling the potential impact of a downturn in China on commodity prices. We can model out the impact, but we’re not experts on the likelihood, scale or timing of a Chinese recession or material downturn. It would be great to have a book that translates Chinese economic developments into analogous US terms, eg, how does China’s shadow banking system compare to the US; what does a Shibor spike mean compared to a LIBOR spike, etc. Stylistically, I would prefer something like the work of Gary Gorton: easy to read, heavy on causal linkages.