Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution by Helen Popper, professor of economics at Santa Clara University.

A country or state – such as, say, Greece or California – without its own currency can’t choose its own monetary policy. Nor can a financially open country that tightly fixes its exchange rate to another country’s currency. In contrast, a country, such as the United Kingdom, with a freely floating exchange rate can choose its own, sovereign, monetary policy. While other countries might influence its policy, they don’t constrain it. The United Kingdom has monetary sovereignty – the ability to conduct its own monetary policy without being tightly tethered to another country’s policy. Monetary sovereignty is what allows countries to direct their monetary policies at their own domestic economies.

In an influential paper and related commentary, Hélène Rey questions the relevance of this view of monetary sovereignty (a view that captures Mundell’s time-honored trilemma, discussed below). Rey argues that increased international financial integration has made monetary sovereignty largely irrelevant. In the same vein, others, such as Sebastian Edwards (paper and commentary), have suggested that bone fide monetary sovereignty has become illusory for emerging market countries.

Economists aside, heated political controversy in many countries – including Argentina, Greece, Iceland, and the United Kingdom – suggest that people on the street believe monetary sovereignty is real and that it’s relevant. Are they wrong? Does monetary sovereignty no longer matter?

Recent Experience

Some countries do indeed enjoy a great deal of monetary sovereignty, while others don’t. We can compare their experiences using recent data. Then, we can ask: have the two groups fared the same?

Below are some basic, macroeconomic comparisons using a sample of 33 emerging and advanced economies. Monetary sovereignty is measured using the techniques in Popper, Mandilaras, and Bird, European Economic Review, 2013. (More on sovereignty measures later.) The remaining, standard data are described in Parsley and Popper, 2015.

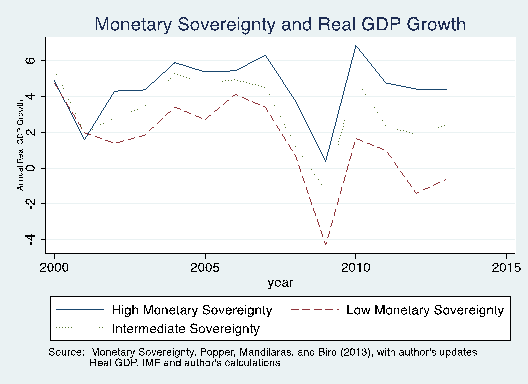

The first figure shows real GDP growth since the year 2000. What we see is that countries with high monetary sovereignty have experienced greater real GDP growth than those without it. Their economies also have rebounded more strongly from the financial crisis than those without monetary sovereignty. The GDP growth of countries with some – but not full – sovereignty falls roughly in the middle.

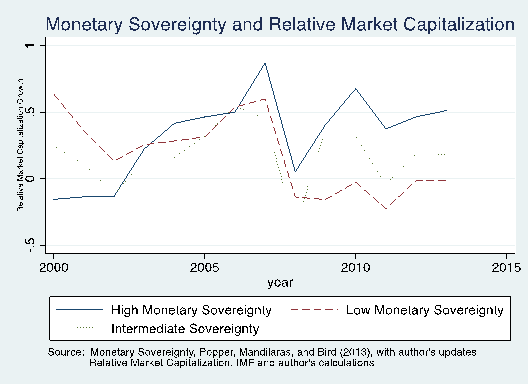

The second figure depicts the countries’ equity market capitalizations relative to the late 1990s. The recent market growth in countries with monetary sovereignty has generally been faster than in the past, while growth in those without monetary sovereignty has been slower.

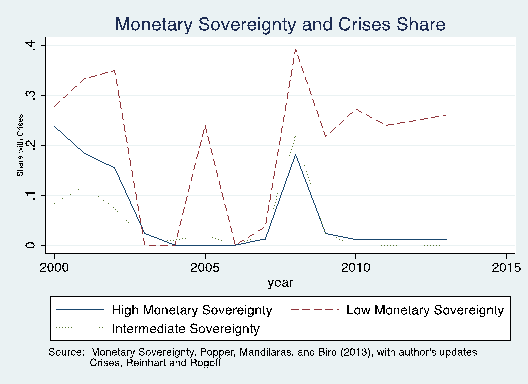

The third figure depicts the incidence of financial crises for each level of monetary sovereignty. The crises are taken from Reinhart and Rogoff’s revised crisis data, and included are: currency, inflation, stock market, banking, and both sovereign and external debt crises. The share that is shown is the number of crises in each sovereignty group divided by the number of countries in each sovereignty group. (The picture is mostly similar when currency crises are excluded.) The figure shows that a disproportionate share of recent crises has occurred in countries lacking monetary sovereignty.

The figures as a whole indicate that the recent macroeconomic experiences of countries with monetary sovereignty have differed from those without it. In some key ways, the experiences of countries with monetary sovereignty have been better. They have had more rapid GDP growth, stronger equity markets than previously, and proportionately fewer crises.

If it weren’t for the recent skepticism of monetary sovereignty, these differences might not be surprising. After all, when a central bank can choose its own monetary policy, one might expect it to choose one that serves its country well, at least in the short term.

Having said that, the Achilles heel of monetary sovereignty has arguably been inflation. The freedom provided by monetary sovereignty can also bring higher inflation. One of the reasons some countries give up their monetary sovereignty is to piggyback onto the policies of another country’s central bank, usually a central bank with an established record of stable prices. Monetary sovereignty is traded in for price stability. This trade-in is borne out here: countries with relatively low monetary sovereignty also have relatively low inflation.

In ongoing work, I find that these differences, including the inflation difference, are statistically significant at standard confidence levels. Despite financial globalization and for whatever reasons, the recent economic experiences of countries with and without monetary sovereignty have differed significantly. In other words, they have not fared the same.

Measures of Monetary Sovereignty

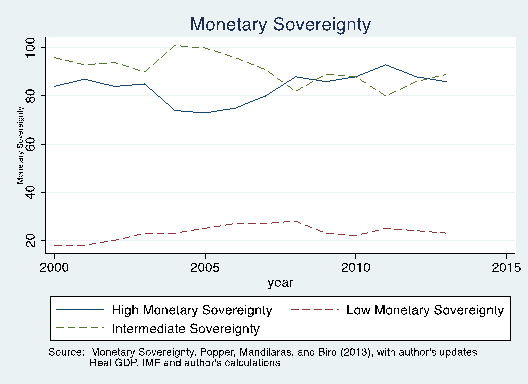

The measures of monetary sovereignty used in the figures above come from Mundell’s classic trilemma: countries enjoy monetary sovereignty only if they give up exchange rate stability or financial openness. Mundell’s trilemma implicitly defines a gauge of monetary sovereignty that can be constructed from data on exchange rate stability and financial openness. The construction of this trilemma gauge is described in complete detail in Popper, Mandilaras, and Bird, European Economic Review, 2013, and in a working paper. The underlying data come from Aizenman, Chinn, and Ito (2010 and 2013, described here).

The trilemma gauge differs from the most-used existing gauge, which relies on interest rate correlations. The correlation idea is that if one country’s monetary policy is tied to another’s, then its interest rates must closely follow the other country’s policy rates. The correlation gauge was important at its inception when it was needed to test the trilemma. (See this seminal paper.) Unfortunately, the correlation gauge is problematic now because it tosses financial globalization into the mix. That is, both globalization and low sovereignty imply high correlations; so, the correlation gauge conflates the two.

Consider the response to the financial crisis. The Federal Reserve aggressively lowered interest rates. So did many other central banks; but not all of them lowered their rates because the Fed did. Some simply lowered their rates because it seemed like the best response to the crisis, irrespective of the Fed’s response. The result is correlated interest rates, but it would be a mistake to take the correlation as evidence of relinquished sovereignty. (Nick Rowe makes this point about Canada.)

In contrast, the trilemma gauge of sovereignty allows us to examine the changes in monetary sovereignty whether or not countries are experiencing the same economic conditions. The figure below provides a sense of recent changes in monetary sovereignty for a large set of countries. It shows the number of countries with differing degrees of monetary sovereignty as measured using the trilemma gauge. A few countries have given up monetary sovereignty during the period, but large changes have not persisted. Interest rates may be more highly correlated, but despite financial globalization, monetary sovereignty does not appear to be going away.

Not Dead Yet

Increased financial globalization has meant that economies are more closely tied to one another in many ways, including through interest rates, risk, and uncertainty. As Hélène Rey importantly points, this calls for greater attention to credit growth and leverage. Increased financial globalization also has meant that governments justifiably take into account other countries’ actions when making their own policies. This is a key take-away from Sebastian Edward’s work. However, increased financial globalization has not meant that governments have relinquished their economic authority altogether. When it comes to monetary policy, the majority of countries still make their own choices. Financial globalization hasn’t killed their monetary sovereignty just yet.

This post written by Helen Popper.

I’m a little confused. Is the thrust of this article that continuing financial globalization will make monetary sovereignty irrelevant? I wonder, given the contagion uncovered in the Great Recession–that the massive leverage and credit growth went unnoticed–might make policy makers a bit wary of jumping ‘all in’ into more international finance. Why would, given recent experience, a monetary sovereign compromise it’s flexibility? Especially if the nation is a large one like the U.S. or China where more national self sufficiency is possible.

Chris: “Is the thrust of this article that continuing financial globalization will make monetary sovereignty irrelevant?”

No. Just the opposite. Monetary sovereignty, measured properly, is still relevant (as shown by the graphs). It’s just that financial globalisation makes it *look like* monetary sovereignty is diminishing (if we don’t measure it properly, and simply look at correlations between nominal interest rates).

Trump and Palin for President. America deserves them both.

I personally thought this was a pretty good analysis, but alas, no Bush bashing, hence no comments.

Thanks Helen. Good post.

“That is, both globalization and low sovereignty imply high correlations; so, the correlation gauge conflates the two. ”

Yep. We could also add that highly correlated underlying shocks would be a third reason we might see high correlations between nominal interest rates. (Imagine two identical countries, hit with identical shocks, each with its own independent central bank, responding exactly the same way.)

I think that what underlies the fallacy you are correctly attacking is something more pervasive: the view that monetary policy *is* interest rate policy. It’s not. Nominal interest rates are just one of many things that are influenced by monetary policy. Exchange rates are another. And so on.

Nick:

Thanks for this (and for the clarifying response to Chris’s comment). You make an excellent point about monetary policy not equaling the interest rate – or the exchange rate. Piling on about the exchange rate, I’ll add that conflating the underlying economics with the central bank’s actions sometimes lead to other mistakes, such as a false impression of exchange rate management, or even manipulation. (This point is discussed in detail in Parsley & Popper, JIMF 2014.) .