The 2% devaluation of the Chinese yuan on Monday, and subsequent 1.6% weakening on Tuesday, was variously described as surprising and stunning. I think it was to be expected, given China’s slowing growth, although there was no particular reason to believe Monday would be the day. In evaluating the effects, one has to first place the drop in context.

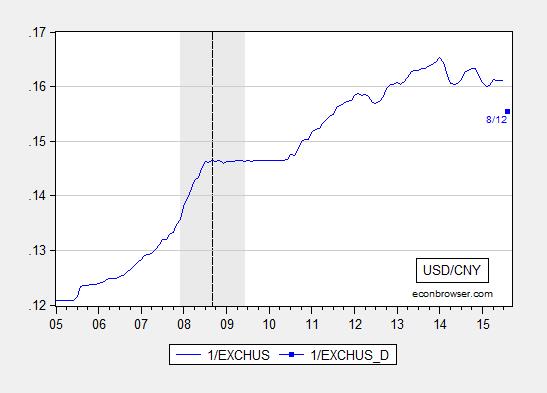

The devaluation against the dollar was quite marked, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: US dollars per Chinese yuan, average per month (blue), and value for 8/12 (blue square). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed line at Lehman (2008M09). Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED.

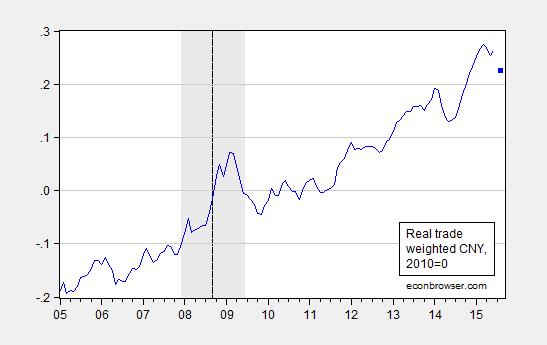

However, it’s important to recall that the dollar has had a rapid ascent over the past year, so that the real trade weighted value of the yuan has also been rising. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Log broad value of real trade weighted Chinese yuan, 2010=0 (blue) and value for 2015M08 assuming 2% depreciation relative to 2015M06. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed line at Lehman (2008M09). A value of 0.23 means that the yuan was 26% stronger in real terms than it was in 2010. Source: BIS and author’s calculations.

In other words, the devaluation has only partly reversed a marked appreciation. (Note the depiction in natural logarithms allows one to see the devaluation in context.)

Already, there is talk of “currency wars”. From Washington Post:

Stephen Roach, a fellow at Yale University who formerly served as a non-executive chairman for Morgan Stanley in Asia, told Bloomberg that the move raised the “possibility of a new and increasingly destabilizing skirmish in the ever-widening global currency war.”

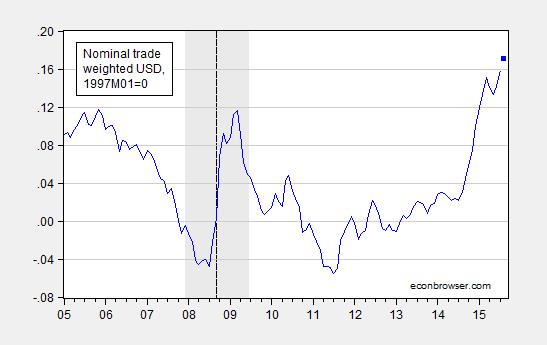

There is no doubt that this move will tend to further appreciate the dollar. China accounts for 21.3% of the weight in the Fed’s broad currency basket dollar index.[1] But as shown in Chinn (2015), several East Asian currencies already quasi-peg to the yuan, so that a weight of about 1/3 is probably more relevant. Figure 3 depicts the implied appreciation of the dollar’s value against a broad basket assuming all other bilateral weights experience zero change, and East Asian currencies move one for one with the yuan.

Figure 3: Log broad value of nominal trade weighted dollar, 1997M01=0 (blue) and value for 2015M08 assuming 2% yuan depreciation relative to 2015M07, along with other East Asian currencies; see text. A value of 0.158 means the dollar was 15.8% stronger in nominal terms than it was in January 1997. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Dashed line at Lehman (2008M09). Source: Federal Reserve Board and author’s calculations.

While the impact is substantial, I think the language of “currency war” is a little overblown. In addition, it’s important to disentangle the impact on markets emanating from the policy action specifically (a weaker yuan has negative implications for US firms exporting to China) from the news component (devaluation being interpreted as Chinese policymaker worry about the economy based on insider information, e.g., here).

Returning to the “currency war” issue, on a point that I’ve stressed before, an expansionary monetary policy that depreciates a currency and only re-allocates aggregate demand will certainly have implications for the international distribution of output and welfare. However, if monetary authorities globally are pursuing a too tight policy, and the Chinese devaluation constrains further tightening (because of aversion to currency appreciation), then it’s not clear what the overall implications are.

Obviously, the outcome depends on what policymakers do. For the US, I believe this is yet more reason to defer monetary tightening [1]. After all, even before the Chinese devaluation, the dollar had appreciated on a broad basis by 13.7% (log terms) in the past year, putting downward pressure on inflation and aggregate demand. Although manufacturing employment some resilience in the last release, I think it’s far too soon to be complacent.

Update, 12PM Pacific:

Additional coverage, from FT1 FT2; Riccadonna/Bloomberg, Yao/Reuters. Arthur Kroeber highlights the fact that a more flexible yuan, is part of the longer term plan of policymakers to make the economy (slightly) less command-and-control:

One irony of the fallout from the central bank’s move to devalue the currency: In the long term, freeing up exchange rates would give it another powerful tool for managing economic slowdowns, just like the one China faces now.

“Having an exchange rate that adjusts means that other parts of the economy, like interest rates or wages, don’t have to adjust so much,” said Arthur Kroeber, the managing director at Gavekal Dragonomics, a financial consultancy in Beijing.

“The economy has clearly been weakening, and basically they have tied one hand behind their back,” he added, “because they’ve been unwilling to let the renminbi go down against the dollar, which is what the market would have done if it had been left to itself.”

“There is no doubt that this move will tend to further appreciate the dollar.”

There may be no doubt, but there are stubborn facts. The dollar index is down more than 1% over these two days.

W.C. Varones: Gee, and gold is up on these two days. Betcha it’s time to buy gold, because 2 days is a trend!

Thanks. Still waiting for the hyperinflation you kept on warning us about.

Menzie,

You seem obsessed with this “hyperinflation” boogeyman. I’ve rarely, if ever, mentioned “hyperinflation” on Econbrowser. While I have mentioned the word “hyperinflation” a number of times on my own blog, most often in discussing the academic and media views of others, I’ve been much more consistently predicting Fed-sponsored asset inflation for the past 5+ years, which has been a fantastic call for anyone with the courage to get on board and buy stocks (or prime real estate).

But if ad hominem is the modus of the day, let’s not forget the time you lost a battle of wits to Sarah Palin.

My point here is one I’ve made before often on this blog: myopic economists use their simplistic models, with far too much confidence, to make predictions about enormously complex economic and market systems. One of the most common mistakes is to look only at first-order effects (e.g. “There is no doubt that this move will tend to further appreciate the dollar. China accounts for 21.3% of the weight in the Fed’s broad currency basket dollar index. But as shown in Chinn (2015), several East Asian currencies already quasi-peg to the yuan, so that a weight of about 1/3 is probably more relevant.”), and ignore important second- and third- order effects.

In this case, the initial reaction of the market is exactly the opposite. A surprise Chinese devaluation resulted in a weaker dollar. The collective wisdom of the market is that your “no doubt” proposition is wrong, and that the China news will have repercussions for Fed policy and the global economy that outweigh the simple effect of Asian currencies’ mathematical weight in the dollar basket.

Often mistaken, never in doubt…

Leaving aside all the arguments of inflation/deflation (ideal monetary policy), isn’t it possible that the devaluation just reflects the artificiality of a peg?

IOW, the market would create X price equality. A peg is at Y. That can’t endure.

Actually I wonder why countries even bother to peg. Why not just run your affairs in USD if that is what you want.

What has been surprising has been the resilience in the core inflation statistics. The risks heading into 2015 were rightly skewed to the downside given the drag from the strengthening USD and drop in commodity prices. However, over the last six months, core CPI up 2.3% SAAR, core PCE up 1.6% SAAR, trimmed-mean PCE inflation up 1.9%. Heading into the year, in December 2014, these measures ran 1.2%, 1.0%, and 1.4%, respectively. Perhaps there is more of lag involved or perhaps the stickier parts of the inflation story are picking up the slack. What is your reading of the literature out there on exchange rate pass through to core consumer prices?

Neil: From Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research (Pandl, Mischaikow) yesterday:

What a model! Where can I buy one? And does it have tail fins?

Core inflation is up because of economic activity. Overall inflation is down because of commodities. I am still waiting for the mythical slowdown and am not seeing it.

The world is at GDP PPP and capital, credit, and trade flow parity between the three major geographical trading blocs.

The post-2007 average trend rate of real GDP per capita and “trade” (Anglo-American imperial trade regime or “globalization”) is decelerating toward 0%.

US and Japanese FDI began fleeing China as long ago as 2013, along with corporations and expats voting with their feet to get while the gettin’ was good.

China reached the similar level of real GDP per capita as did the US in 1930, the UK in the 1950s, France and Germany in the 1960s, and Japan in the late 1960s. The 5- and 10-year constant-US$ price of oil during these periods was $20 or below. Today the price is $95-$100.

Since reaching the US-equivalent real GDP per capita in 1930, China has grown money supply at a banana republic-like compounding doubling time of 3 1/2 to 5 years, creating the largest credit and fixed investment bubbles as a share of GDP in world history, far surpassing the US in the 1920s and 1990s-2000s and Japan in the 1980s.

What we are witnessing is an incipient 1930s-like debt-deflationary implosion in China and the predictable response in terms of currency devaluation and gov’t intervention in the financial markets.

Because of regional GDP PPP and slowing “trade”, the US-China client-state “trade” relationship, China’s closed financial system, non-convertible currency, and massive debt to GDP and overcapacity, China’s devaluation will have little more than a one-off effect on China’s balance of payments accounting, as in the case of Germany in the EZ and Japan, both cases having likely played out already with limited benefit to the domestic economies.

The implied outcome hereafter is for all major fiat digital debt-money currencies trending toward par with one another, growth of global real GDP per capita and trade ceasing, gov’t deficits to GDP rising, and central banks resuming QEternity, even piling on to prevent financial asset deflation and contraction of nominal GDP.

We’re in the late stages of the ongoing end game of the post-Bretton Woods fiat currency regime and global historical experiment. The result is massive financial asset bubbles everywhere as a share of wages and GDP; worsening wealth and income inequality; decelerating productivity and real GDP per capita; Wall St financiers and speculators and central and TBTE banks having captured the economy and gov’ts; and a perpetual state of risk that all manner of potential “exogenous shocks” will stall the economy, crash the financial markets, and precipitate another perception of existential risk and central bank and gov’t panicked printing of trillions of dollars in additional bank reserves.

The blue bus or the crazy train? Choose your preferred mode of transportation speeding toward the financial and economic brick wall.

All the children are insane . . .

Waiting for the summer rain (and another hit off the QE bong).

Bullet train, BC! Massive unintended consequences of utterly asinine NIRPs (negative i-rate policies) and Night of the Living Dead QEs wrapped tightly in a never-before-seen high energy projectile on a collision course with a destiny the likes of which the world has never seen.

JBH, you thrice-upped me there, at least. 😀 Gallows humor is a necessary relief under the circumstances.

great post

time will tell

Menzie,

Good article!

The update is a little silly though (I know it is from others).

China has been moving away from the model given them be Robert Mundell and the result has been movement toward economic chaos. It appears that the western trained Chinese economists are winning the day as they apply failed demand theory policies.

The saying is “Dance with the one who brung you.” I the case of China that means the supply theory policies of Mundell that made China the second largest economy in the world. But as is so often the case, once they arrived at the dance their heads were turned and they begin to dance with the ones in the cheap makeup.

My view of the matter is here: http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/8/13/oil-and-chinas-devaluation-an-alternative-view

Not really so different than Menzie’s, but as you can imagine, with an oil twist.

I might add that I think it may herald a broader change of policy in China.

was only a storm in a glass of water.

Good points. What we’re seeing here is an inevitable side-effect of managing exchange rates: decisions to ease up on efforts to resist market forces cause alarm and uncertainty. The background indeed is that China has been spending reserves to appreciate the yuan against most of its trade partners. Also, given the large pent-up demand for savings alternatives to bank deposits, liberalizing exchange of the yuan and fostering expectations of further liberalization exacerbates downward pressure.

Although I don’t think China’s leadership really meant it this way – they were just adhering to an old habit of pegging to the dollar – this is probably the most important thing they have done to rebalance the economy. Basically, central authorities ceded to exporters the share of real value that was previously socked away as FX reserves, and to some extent exporters ceded value to labor in terms of higher real wages (especially in terms of international purchasing power). On the other hand, for many if not most exporters it’s more a case of the surplus aka value add having been shrunk by overinvestment.

Nony,

Having lived in an economy that pegs its currency to the US dollar for more than 30 years (Hong Kong), I can tell you it is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, the exchange rate isn’t whipsawed by daily capital flows that dwarf (daily) GDP. On the other hand, when our economy isn’t in sync with that of the US, we get either high inflation or deep deflation.

Nony,

Having lived in an economy that pegs its currency to the US dollar for more than 30 years (Hong Kong), I can tell you it is a mixed blessing. On the one hand, the exchange rate isn’t whipsawed by daily capital flows that dwarf (daily) GDP. On the other hand, when our economy isn’t in sync with that of the US, we get either high inflation or deep deflation.