Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Maria Muniagurria, faculty member in Economics at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

A little over two months ago, Mauricio Macri began his tenure as president after his coalition of center-right parties prevailed over the ruling party’s candidate by a small margin.

This is the first significant political change in many years, since the left leaning branch of “peronist” party held the executive office since 2003 (both husband and wife Nestor and Cristina Kichner held the presidency). The following statement by former Finance Minister Kicillof summarizes the previous administration’s approach to economic policy: “since 2003, Argentina has been implementing … an economic model of growth with social inclusion, where inclusion and redistribution of income are seen as a precondition for growth and not vice-versa, as stated by the mainstream economic precepts” (October 2015 statement to the IMF).

Very favorable primary commodity prices and high export taxes financed large government expenditures (social programs, variety of subsidies) for many years but when the conditions started to reverse the country slipped into a path characterized by government deficits, inflation and foreign exchange controls. The 2001 default and the subsequent one in 2014 resulted in an almost complete exclusion of the country from international financial markets and since 2007 the government engaged in the manipulation of statistical data.

Since it took office last December 10th, the new administration has taken a number of important steps towards the elimination of major distortions, restoration of data transparency and return to international financial markets in the midst of a complicated political and social environment.

The economic team inherited a very difficult situation with an inflation rate reaching about 25-30 % a year, a government deficit of 7.1% of GDP and almost depleted foreign exchange reserves.

The main economic policy measures have been: 1) elimination of the foreign currency controls (“cepo” or “clamp”) and unification of the foreign exchange market; 2) declaration of an “statistical emergency”; 3) partial elimination of utility subsidies; 4) decrease of export taxes on soy (from 35% to 30%) and elimination of those for beef, wheat and corn, 5) negotiations towards the return of the country international financial markets (negotiations with debt “holdouts” ).

Data Transparency Issues and Inflation

Until 2007, Argentina had a high quality and internationally recognized national statistical office: the Instituto Nacional de Estadisticas y Censos (INDEC). At that time, political considerations motivated an “intervention” designed first to manipulate the inflation index. Unqualified political appointees replaced skilled statisticians and irregularities were commonplace both in data collection and reporting. Several indicators were no longer reported (poverty data among them), “new indexes” replaced long running ones and the unreliability of the economic data reported was documented by many (see for example Cavallo 2012)

In 2012, the IMF issued a warning to Argentine (Reuters) for not taking the necessary steps to improve the quality of its reported data (after earlier complains were not addressed) and proceeded to a motion of censure/official reprimand in 2013 (Bloomberg). The displaced statisticians received support from the American Statistical Association and in 2012 The Economist removed official price data from its tables.

The new government identified as a top priority the “reconstruction” of INDEC and the return to accurate data reporting. A “statistical emergency” was declared in December with two goals: facilitate the removal of unqualified staff /political appointees and temporarily suspend the report of inaccurate data while revisions are taking place. The task has proven to be quite challenging since there is political urgency to come up with an official inflation indicator (used by the powerful trade unions for salary negotiations and for many indexed contracts) and statisticians differ in their assessment of the time needed to produce quality data (see Buenos Aires Herald 2-16-16 for an account of a recent departure from the team).

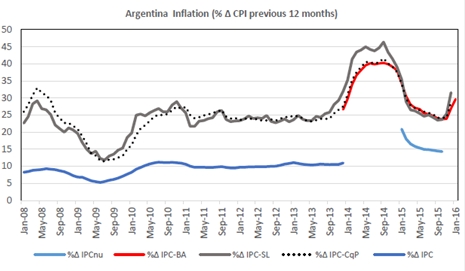

After 2007, alternative price indexes gained relevance and new ones were calculated and widely used by economic actors and politicians. Figure 1 shows the large discrepancy between INDEC data (blue lines, two versions of the CPI) and alternative ones. The gray line shows data from the statistical office of the province of San Luis, the red one is from the statistical office of the city of Buenos Aires and the dotted line is from a private group.

Figure 1: Sources: INDEC, Cosas que Pasan, DPEyC-San Luis, DGEyC-Ciudad de Buenos Aires

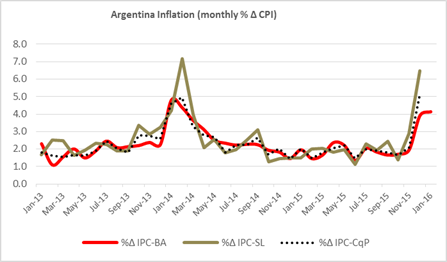

Inflation surged in November and December (even before the official change of government) fueled by expectations regarding the future value of the dollar.

Figure 2: Sources: Cosas que Pasan, DPEyC-San Luis, DGEyC-Ciudad de Buenos Aires

Foreign Exchange / Trade and Finance

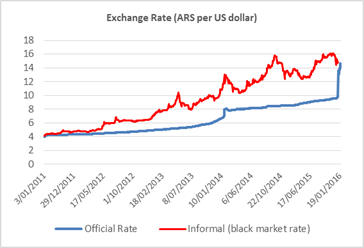

In November 2011 the government began to impose strict controls on the foreign exchange markets (trying to stop the decrease of the Central Bank’s foreign reserves) what made almost impossible for ordinary citizens to purchase dollars and severely restricted imports. The “cepo” (or clamp) resulted in the emergence of a black market for foreign currency, and the “official” value of the dollar was kept artificially low. Exports suffered (producers were hoarding grain), import restrictions severely affected the availability of industrial inputs, and tourists expenses overseas (at an undervalued exchange rate) ballooned.

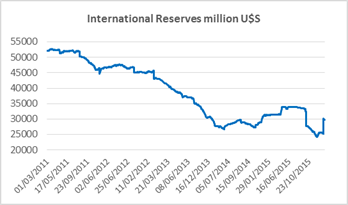

On December 16, after securing additional dollar reserves (due to a Yuan-dollar swap with China) and later a bridge loan from a group of international banks, the government fulfilled its campaign promise of lifting the “cepo”. The exchange rate adjusted: there was an immediate devaluation of 35% and a gradual depreciation of the peso afterwards to arrive to a 55% devaluation since the lifting of the “cepo”. The market has been operating without Central Bank intervention – except for one day last week – what should be considered as an important success. Figure 3 shows the paths of the official and black market rates and Figure 4 that of the international reserves.

Since the 2001 default, Argentina has been unable to borrow internationally and has been involved in a prolonged dispute with “holdout” bondholders (the 7% of that did not accept the 2005-7 restructuring). One of the judicial rulings (in New York courts) forced the default on the restructured debt in 2014. The current government has made significant progress in resolving the dispute and has stated its desire to return to the international financial markets (see The Economist 2-6-16).

Figure 3: Source: Diario La Nación

Figure 4: Source: BCRA (Argentine Central Bank) Estadísticas.

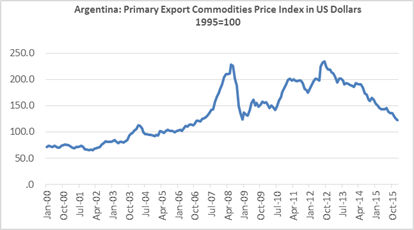

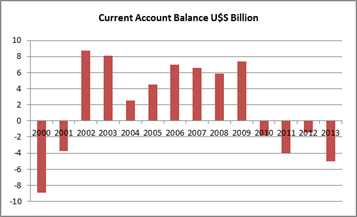

High primary commodity prices resulted in a favorable Current Account for many years but the decline in those prices and large energy imports moved the balance into negative territory (see Figures 5 and 6). The new economic team reduced export taxes on soy by 5% and eliminated those on wheat, corn and beef. These adjustments together with the devaluation are expected to increase exports and the local supply of dollars.

Figure 5: Source: BCRA (Argentine Central Bank) Estadísticas. (Weights are based on a commodity’s importance in Argentina’s exports)

Figure 6: Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2015

The Fiscal Situation

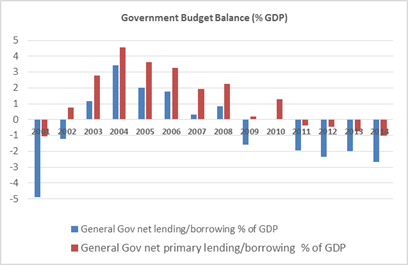

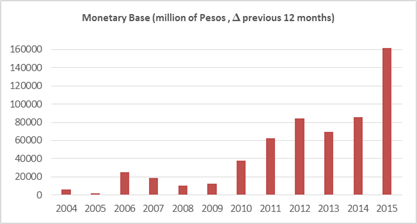

Argentina has a long history of lack of fiscal discipline but fiscal surpluses during the six years following the 2001 crisis provided a remarkable exception. The situation deteriorated after 2008, the deficits returned and the inability to finance them with debt left monetary emission as the only alternative to finance them (see Figures 7 and 8 and Maselli y Nicolini 2014).

Figure 7: Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2015

Figure 8: Source: IMF World Economic Outlook database, October 2015

Fiscal Plan and Inflation Targets, Central Bank Priorities

In early January, Finance Minister Alfonso Prat-Gay announced fiscal and inflationary targets stressing that government will stop financing deficits through transfers from the Central Bank to the treasury (monetary emission). The inherited primary fiscal deficit for 2015 was 5.8 % of GDP and increased to 7.1 % when interests and unpaid debts are included. The target is to reduce it by about 1.5 % GDP points per year to maintain governability. The inflation targets are 20-15% for the current year and 14%, 10% and 5% for the next ones.

According to Prat-Gay, President Macri directed him to keep social spending (welfare programs) untouched, increase investment if possible and find ways to reduce waste in every central government agency. The plan also includes removing subsidies to energy purchases in Buenos Aires, reducing the number of public employees that are not engaged in productive work (political appointees unqualified or not needed) while benefiting vulnerable citizens by cutting value added taxes on essential goods and increasing the threshold and brackets at which workers begin paying income taxes (Bloomberg 1-13-16, Enernews 1-13-16). The details of how the deficit will be financed during the first couple of years have not been announced.

Central Bank President Federico Sturzeneger also moved quickly to announce the bank’s policy objectives for 2016 and identified price stability as one of his main his priorities (also one of the missions of the bank according to its funding laws). He pointed out that in the past years, Treasury demands to finance fiscal shortfalls hindered the ability of the bank to fulfill this crucial part of its mission.

There is no doubt that lowering the inflation rate and reducing fiscal unbalances while maintaining governability will require not only sound economic policy but smart political decisions and a big dose of good luck. Macri’s team is very well qualified to take on this difficult task …so we hope for the best.

References

American Statistical Association, AMSTATNews

Banco Central de la Republica Argentina (BCRA)

Maselli, Luis y Nicolini , Juan Pablo. Monitor Fiscal , Marzo 2014, Foro Economico

Ministerio de Economía: Plan Fiscal y Metas de Inflación 2016-19

This post written by Maria Muniagurria.

Thanks for the quotations!

Great to see a post on Argentina.

Meanwhile, latest from me at CNBC: OPEC can cut oil production

http://pub.cnbc.com/2016/02/23/how-saudis-can-cut-oil-production-commentary.html

Nice update on Argentina – beautiful country. Prat-Gay and Sturzenegger are certainly very capable men.

But… how long will this last? How long before the Peronist Party ravages Argentina again? How long before the voters in Argentina get fed up with sensible policies and wander to populism again? How long before a populist demagogue à la Kirchner rises again and destroys everything that Macri attempted to repair?

My bet? Not long at all. Because that is the story of Argentina and its voters. Mind you, Macri did not win a huge victory – he eked out a victory. Almost half the voters voted for Cristina Kirchner’s heir apparent Daniel Scioli. And Argentina Parliament (el Congreso) is still in Peronist hands. It does not take too much to win over a few more voters with easy and populist promises (à la Eva Perón), so that the Peronists can reign unhibited.

Macri is a welcome change. But it will not last. That is Argentina’s story since 1946, when Juan Domingo Perón came to power for the first time. It was all downhill since then, with a few little upswings in between, but to no avail. That will never change in Argentina, ever.

If you put in an FAA, there would be no recurrence of Peronism.

What’s an FAA…?

Fiscal Accountability Act. Paying politicians for performance.

Essentially, the presumption is that governments face three different objective functions: liberal (sustainable growth and prosperity); conservative (strength, conformity and risk minimization); and egalitarianism (redistributing income and wealth downward). As these three objectives conflict and are not resolved, politicians are given sway to pursue their own objectives–it gives rise to a principal-agent problem which, in the case of Argentina, is historically resolved through external debt and monetization of deficits, as well as the slew of counter-productive policies which inevitably follow: currency controls, import/export controls, price controls, dollarization, weird taxes, etc.

Using an FAA, you give politicians a clear monetary (pecuniary) incentive to provide sustainable prosperity.

Only in economics is this a controversial notion, but there you have it.

The five key countries to try out such an approach, in order, are: Argentina, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Spain.

See more here, for a template for Greece:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/2/19/a-program-for-greece

And here, for a US version:

http://www.prienga.com/blog/2015/3/19/a-bonus-plan-for-politicians

To your point:

https://ca.news.yahoo.com/argentinas-president-faces-strike-discontent-prices-leap-050534115–business.html

It will be hard for the new president and his team to match the GDP growth that occurred under the Kirchners (albeit from a very depressed base). They will have to deliver some solid results or else they risk being one term wonders. That said the Justicialists well deserved defeat. They had become increasingly corrupt, autocratic and divorced from economic reality.

Corruption is almost always a serious problem, whether it’s conventional neo-liberal policies that enrich those who can afford to buy government debt and gain compound interest that sucks the lifeblood out of a nation, or the pro public governments where initial successes grow internal corruption and that house falls down too. Don’t have a remedy for greed, unfortunately. What I do believe is that neo-liberal economics and the private banking industry it promotes is inimical to sustainable growth. Especially for developing countries, although its doing a pretty good job of weakening western developed economies too. My guess is that this new regime, solidly neo liberal, might induce some economic growth, but the revenue from that growth will not benefit Argentina. It will benefit international finance and foreign debt holders.

An FAA essentially takes care of the corruption problem.

This paper is a shame. Noting about the exterior debt (reduced drastically, in dollars, by the Kirchner administration), which make the country much dependent on international capital markets, about the rebuilding of industry, about inequality (reduced a lot), about education (from 3 to 6% of GNP), about low unemployment. Your tables show that even inflation was going downward in 2014 … until the Macri’s election, who openly declared that he will “liberate” the dollar and suppress the taxes on exports – so that productors rised their prices, “rationally” expecting that Macri will be electif.

You are “anti-austerian” fort he USA, Europe and Japan, but desagree when the argentinian minister KIcilov, a declared keynesian, do what you preconise.

Where did you get the 7.1 government deficit number from?

Tks

The primary source is Prat-Gay’s presentation on Jan 13 :

Ministerio de Economía: Plan Fiscal y Metas de Inflación 2016-19 (video: http://www.economia.gob.ar/plan-fiscal-y-metas-de-inflacion-2016-2019/ ).

Two english language news reports on his presentation can be found:

http://en.mercopress.com/2016/01/14/argentina-targets-25-inflation-and-fiscal-deficit-of-4.8-of-gdp-this-year

https://www.itau.com.br/itaubba-pt/analises-economicas/publicacoes/latam-talking-points/argentina-minister-sets-fiscal-and-monetary-targets-for-2016-2019