What does a conventional (estimated) macroeconometric model imply for a sustained 7.7% increase in government consumption and investment as a share of GDP in terms of output.

Table 19 in Friedman (2016) provides a tabulation of annual expenditures implied by his understanding of the Sanders economic plan. Not all of the spending is government consumption and investment — some is government transfers. However, if I assume that the marginal propensity to consume out of these transfers is unit, then the calculation is simplified (in any case, the big expenditures are health care).

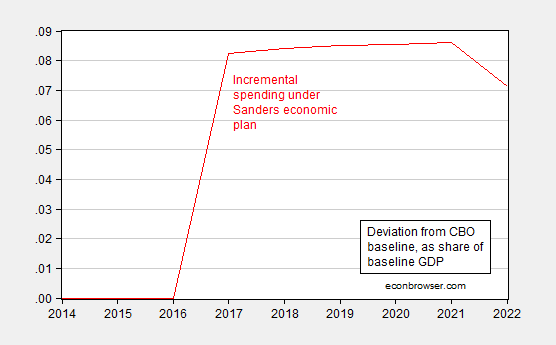

Figure 1 depicts the deviation from CBO (January 2016) baseline, as a share of baseline GDP.

Figure 1: Deviation from CBO baseline in government consumption and investment, as a share of CBO baseline GDP, in Ch.09$, by fiscal year. Source: CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, 2016-2022 (January 2016); Friedman (2016), Table 19, and author’s calculations.

On average, government spending (will be higher by 7.7 percentage points of baseline GDP). I can just assume constant spending over the sample period, and use the multipliers from a given study to determine the resulting output. In this case, I use the OECD’s New Global Model, described in this 2010 working paper. Here’s a short description of the macroeconometric model:

…Compared with its predecessors, the new model is more compact and regionally aggregated, but gives more weight to the focus of policy interests in global trade and financial linkages. The country model structures typically combine short-term Keynesian-type dynamics with a consistent long-run neo-classical supply-side. While retaining a conventional treatment of international trade and payments linkages, the model has a greater degree of stock-flow consistency, with explicit modelling of domestic and international assets, liabilities and associated income streams. Account is also taken of the influence of financial and housing market developments on asset valuation and domestic expenditures via house and equity prices, interest rates and exchange rates. As a result, the model gives more prominence to wealth and wealth effects in determining longer-term outcomes and the role of asset prices in the transmission of international shocks both to goods and financial markets.

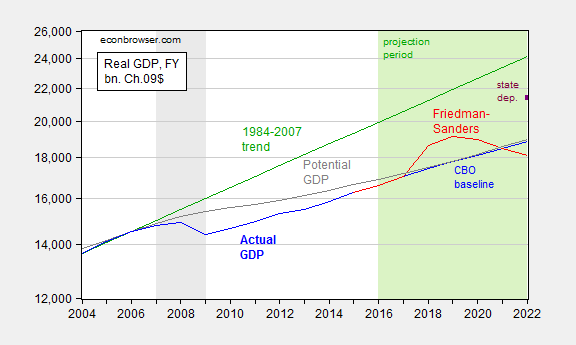

I don’t take into account any of the supply-side effects Friedman outlined (impact on participation rate, for instance). Also, deficits are endogenous, assumed to be stabilized by way of general tax increases, instead of increases in tax progressivity, and taxes on financial transactions. [Specifically in the model, “…the fiscal rule was set to raise direct taxes by approximately one fifth (per annum) of the deviation in the deficit as a percentage of GDP from its baseline path. In the present case, for the countries undertaking fiscal stimulus, this implies more-or-less linear increases in household taxes, rising to be approximately 1 percentage point higher by the fifth year of the shock.”] Hence, the calculation incorporates only the demand side spending effects. Figure 2 shows the deviation from CBO baseline.

Figure 2: Output, in bn Ch.09$ (blue), output under Friedman scenario using OECD (2010) multipliers (red), output under Friedman scenario using Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012) recession multiplier of 1.75 (purple square at 2022), CBO potential GDP (gray) and 1984-2007 trend, all by fiscal year. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray; projection period shaded light green. Source: CBO, Budget and Economic Outlook, 2016-2022 (January 2016); Friedman (2016), Table 19, OECD (2010), Table 3, Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012), and author’s calculations.

In this calculation, output reverts fairly quickly toward baseline even with a massive increase in spending. This reflects the neoclassical assumptions built into the model in the long run; implicitly it also reflects the assumption that one is not too far away from potential GDP when the stimulus is undertaken. Hence, as I indicated in this post, in the absence of assuming a flat aggregate supply curve, the assumption regarding the initial extent of economic slack is critical. If indeed the current output gap is -18% or so, then likely the multiplier might be bigger than 1, and perhaps is close to 1.75, as noted in this post. If on the other hand, output is already close to potential in FY2017 (when the spending is assumed to begin), then the multiplier might be closer to 0.5.

So, where you think you will end up depends a lot on where you think you are now…

All of these comparisons assume that the 1984-2007 trend is the appropriate baseline. Do you think this baseline is reasonable for the next 15-20 years (independent of the Friedman model), taking into consideration a) the growth in debt and debt ratios over the 1984-2007 period, b) the decline in interest rates and debt service costs over this period, c) the demographics of that period compared to the future 15-20 years, and d) the cash flow issues at the Federal, state, and local levels associated with meeting the various entitlement, pension, and other post-retirement obligations over the next 15-20 years?

Harry Chernoff: No. (Actually, only the “state dependent” scenario [purple square]) depends on the 1984-2007 trend in Figure 2.)

More government spending isn’t the answer. Most college graduates and those with no college degree end up with low-paying jobs, while some college graduates with the “right” degrees end up with high-paying jobs. Since prices have been depressed from so many low-paying jobs, the high-paid workers have benefited at the expense of the low-paid workers. To reduce that gap, the minimum wage should be increased, e.g. to $15 an hour, and to compensate for greater unemployment, or the greater burden on businesses, regulations and taxes should be reduced.

Seems as if the focus is wrong. While it is interesting to analyze the Sanders’ or the Trump or the Clinton plans, the real question (to me) is “How do we return to the pre-2008 trend?

You mean the housing bubble or, before that, the Nasdaq bubble?

Peak, since the trend is from 1984, one would think those bubbles and crashes might work themselves out. Still, your point is taken. 2007 was an artificially high point based on unfounded optimism assisted by fraud. Whenever you start from a low point and go to a high point you get an upward trend. If that high point is an anomaly, you get an unrepresentative trend.

So, the question remains: what should be the actions to get the country back to “optimal” growth?

“So, the question remains: what should be the actions to get the country back to “optimal” growth?”

but what exactly is optimal growth? it is probably not has high as you think it should be. one may desire a higher growth, but in reality you may not be able to achieve that growth. optimal growth is a function of the present and future conditions, not the past state. 1984 trends should have no bearing on defining optimal growth in 2016 and beyond.

Baffling… Menzie used the 1984-2007 trend as the comparison for evaluating Sanders’ economic plan, so perhaps he felt that was both desirable and optimal. Nevertheless, the question remains, “What has to be done to restore over two decades of growth trend?” Or has the seven years of Obama’s policies made that impossible or improbable?

Reading Peak Trader’s comments, he seems to believe that:

1. Minimum wages need to be increased (create demand through higher low-end wages)

2. Deregulation of business (overregulation)

3. Tax cuts for the middle class (eliminate progressive taxes on the “middle class,”)

4. Tort reform (reducing lawsuits)

But my questions would be: how do you force higher wages without destroying the competitiveness of businesses and the loss of jobs to foreign manufacturers; what specific regulations should be eliminated and how would that impact safety, health, or environment; would tax cuts really stimulate the economy enough to increase tax revenues to reduce national debt or would the debt necessarily have to soar; and what actions beyond penalizing frivolous lawsuits would stimulate the economy while still holding accountable those who have harmed others?

Wouldn’t, for example, corporate tax cuts help improve the global competitiveness of our corporations? Wouldn’t eliminating the heavy-handed bureaucracy in health care stem the sharply rising costs and allow greater consumer spending elsewhere? Wouldn’t the elimination of regressive fees and taxes added to utility bills and other transactions allow greater consumer spending elsewhere? So many other questions.

Just asking….

Bruce Hall, when wages are too low, you don’t destroy anything correcting for a “market failure.”

If the costs of regulations are too high, or too much, then it becomes destructive. Regulations and GDP should grow together.

Cutting taxes raises growth. When growth is achieved, then raising taxes can slow growth to a sustainable rate.

Anyway, wages can be raised, while lowering other costs of production and raising productivity.

Regulations (and lawsuits) have costs in time, effort, and money. Imposing regulations too quickly slows growth, until the economy becomes large enough to absorb those regulations.

Bruce Hall, I answered your question above. We need to correct the structural problems of too low wages overregulation, and more progressive taxes on the “middle class,” along with reducing lawsuits.

We need to make it easier to start and expand a business, create demand through higher low-end wages, which will also attract idle labor into the workforce, to create even more demand. Consequently, taxpayers will be created, rather than spending on the unemployed and underemployed, including through tax credits (where there’s real fraud). Higher wages will make capital relatively cheaper, to raise productivity and create skilled jobs (in capital equipment).

Yes, as Krugman would say, we need a new bubble!

Menzie Hence, as I indicated in this post, in the absence of assuming a flat aggregate supply curve, the assumption regarding the initial extent of economic slack are critical.

My reading of Friedman’s paper is that he is assuming a “flat-ish” AS curve, but beyond that he is also assuming a shift in the AS curve. So for example, some of Sanders’ proposals might budge people who are not currently in the labor force to join the labor force. A higher minimum wage would also encourage immigration, which would be a labor supply side response to higher wages. But he also assumes a shift in the AS curve as well as movement along that curve. For example, free college education would have a labor augmenting effect and push down the AS curve. In footnote #16 Friedman says that inflation would start to increase (up to 3%) assuming monetary passivity, so he seems to accept that there would be at least some upward slope in the AS curve. That’s why I would say it’s “flat-ish” rather than flat. In that same footnote he recognizes that the fiscal multiplier will shrink over time. My view is that the Sanders plan resembles filling an inside straight in poker. Taken on their own, many of the individual assumptions in the Sanders plan are plausible…or at least not completely implausible. But the chances that everything falls the right way are crazy wrongheaded. The plan also neglects feedback effects that will work against a downward shift in the AS; e.g., Medicare for all and a higher minimum wage would have both income and substitution effects for the labor supply curve, so it’s not clear which effect would be dominant.

In all fairness to Friedman, I did not interpret his paper as his proposal for a President Sanders. My take is that he was simply trying to flesh out the Sanders program as a pedagogical exercises. Just based on his paper I have no idea whether he agrees with Sanders’ economic plan or not. My guess is that he may not since he said he was a Clinton supporter. I know that some have criticized Friedman for not putting out an actual economic model. I don’t think Friedman’s intent was to cobble together a model. My reading is that he simply wanted to document what Sanders’ advisors were saying when he interviewed them. So the blame for the lack of a coherent and formal model should really be directed at the Sanders campaign team rather than Friedman.

2slugbaits: There are (at least) two ways of getting at an estimate of a policy’s effect. One is to run it through a model, missing some details along the way. Another is to do a bean-counting exercise, and hoping the total is the sum of the parts. My view is that an AS-AD framework highlights the point that in order to boost output, a higher long run potential GDP is not enough — higher aggregate demand is also necessary to achieve higher output.

Peak Trader, “Bruce Hall, when wages are too low, you don’t destroy anything correcting for a “market failure.””

You “destroy” jobs through efficiency as the offset to higher wages (Anyway, wages can be raised, while lowering other costs of production and raising productivity.) The “market failure” is forcing higher wages and benefits and regulations and taxes. When efficiencies are insufficient to offset foreign competition advantage of lower labor costs (and maybe state subsidies), production and jobs move overseas.

Take a look at automotive production and the number of jobs now versus 20 years ago… or electronics… or clothing… or any number of industries. There is no “free lunch” of higher wages just because you want them. http://www.aei.org/publication/early-evidence-suggests-that-seattles-radical-experiment-might-be-a-model-for-the-rest-of-the-nation-not-to-follow/

That should read, “The “market failure” is from forcing higher wages and benefits and regulations and taxes.”

The (positive) income effect may be stronger than the (negative) employment effect, up to some wage level, other production costs are reduced (e.g. turnover), and productivity increases. The increased demand can generate employment and attract idle labor generating more demand. The economy may move towards full employment.

Your assumption is that higher wages drive higher productivity. If that were the case in manufacturing, the best compensation would be piecework. Actually, investing in technology drives higher productivity by enabling fewer workers to do the same amount of work (or the same number of workers to do more work). Automotive assembly operations is a great example of that. While that allows employers to figure something like “higher revenue from investment – cost of investment – cost of higher wages = profit change, the logical extension is to eliminate … as much as possible … the “cost of higher wages” variable by eliminating as many employees as possible. Automating McDonalds? Robotic assembly line.

It would seem that the more you push for artificially high mandated wages, the greater the incentive to eliminate the wage earners.

Productivity has a negative effect on prices and with higher wages, demand increases. Moreover, high-skilled jobs are created in capital equipment.

Of course, an entire industry can move to another country where labor can be easily exploited, there are too few regulations, and taxes are too low.

In effect, one country allows another to exploit it and the exploiting country has no control over the other country’s (poor) economic policies.

Yet, the exploiting country can compete with a foreign country with much higher wages, regulations, and taxes, because it’s much more productive with efficiencies in production.

“The “market failure” is forcing higher wages and benefits and regulations and taxes. ”

bruce, for those making the minimum wage, they very well are receiving welfare benefits as well, since the minimum wage does not move many out of poverty levels. thus the businesses who hire those folks at minimum wages are actually beings subsidized by the government to take their employees out of poverty. this is a market failure. you probably have less welfare, and more actual work for pay, with a higher minimum wage.

Baffling, the minimum wage was never intended to be a career path. Those who do not take advantage of the subsidies they received (earned income credits, etc.) and are content to not improve their skills (on their own time) are not the fault of the businesses for which they work. The link I provided earlier shows that your conjecture (you probably have less welfare, and more actual work for pay, with a higher minimum wage) is not working out very well in Seattle which has lead the way in mandating higher wages.

“Those who do not take advantage of the subsidies they received…”

the companies also receive the subsidy, so that they are able to pay poverty level wages and make a profit on those wages. why not suggest the companies are also failing to take advantage of those subsidies? perhaps they could provide training programs to their workers in light of this government subsidy? there was a time companies actually invested in their workers future, perhaps we should reconsider that approach for the future?

Demographics is destiny. We’re toast.