Today we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Pierre Siklos, Professor of Economics at Wilfrid Laurier University.

The Great Recession of 2008-9 was preceded by the Great Moderation, a period thought to have lasted around 20 years. Nevertheless, as we approach a decade since the Global or Great Financial Crisis (GFC) erupted, there is impatience with the state of the global economy even if recent data suggest more optimism than even a year ago.

Unsurprisingly, the last decade has produced a flood of books that seek to understand what happened and how future crises can be avoided. I have waded into this debate with my own take on recent monetary policy. Central Bank Into the Breach: From Triumph to Crisis and the Road Ahead (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017) examines the positions taken by central banks over the past decade or so, how the crisis shaped the thinking of central bankers more generally, and what the future might hold for the place monetary authorities occupy as one of the institutions responsible for economic stabilization. (Data here).

Central bankers became fond of repeating to the public that they were following a rule, albeit flexibly. Of course, flexibility taken to an extreme implies that rules are not being followed. As a result, a backlash against how central banks conduct policy emerged and has yet to dissipate. This partly explains continued efforts in the U.S. Congress to legislate policy rules in one manner or another. The Fed is correct to note that a combination of “judgment” based on a wide variety of data, together with a recognition that the economy is complex as noted in the July 2017 Monetary Policy Report (see pages 36-39), are essential ingredients in delivering good monetary policy. What is under-emphasized, however, is that successful monetary policy also demands transparency and clarity. These are equally critical ingredients and discussions around policy rules are not only helpful but essential in contributing to accountability. It forces the institution to publicly explain the complexities it faces and how its decision-making avoids being a slave to a formula, however simple.

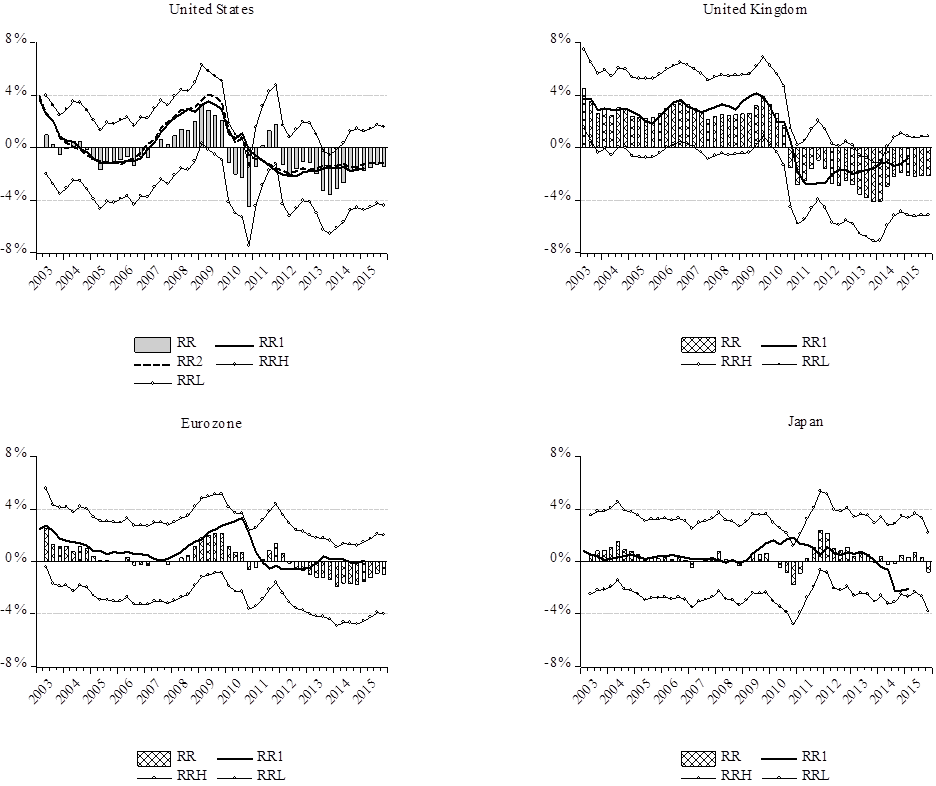

When I began writing this book, almost three years ago, research was surfacing that told us that “normal” is not the pre-2007 state of affairs. Instead, slower economic growth and permanently lower interest rates lay ahead. I still recall participating in a panel session at the Bank of Canada in September 2004 that was devoted to the measurement and usefulness of the “neutral” interest rate. This concept conveys the degree to which the stance of monetary policy is consistent with stable inflation while encouraging economic activity to operate at potential. For a time the concept was thought by central bankers as something to be avoided in public discourse because of the difficulties of explaining a rather arcane concept. The consensus was that, as critically important as the concept of a neutral or natural rate is, estimates are subject to a sufficient amount of uncertainty as to be very imprecise. Yet, more than a decade later, new estimates are being debated in public as if the published point estimates that suggest a downward trend in recent years are sufficiently precise as to confirm that a new era of secular stagnation is under way. Well over a decade since that conference, the lack of precision about an unobservable variable remains large and it is far from clear where we stand. The Figure below provides an illustration of the range of values that the neutral or equilibrium real rate can take is a selection of economies (more examples are also considered in the book).

Note: The figure reproduces part of Figure 7.6 in Siklos (2017). RR is an estimate of the equilibrium real interest rate using CPI inflation. RR1 is an estimate based on using core inflation (except Switzerland). RRH and RRL are proxies for the confidence interval (H means high, L means low). These assume a ±3% variation around the mean estimates based on CPI inflation. Also, see the text for additional details.

As if all this is not enough, the notion that simple rules can be followed flexibly leaving aside a role for the stability of the financial sector, has now been replaced by difficult questions about how to simultaneously manage inflation control and mitigate the risk of another financial crisis through macroprudential means. Decades after the politics were largely taken out of monetary policy, the situation has been reversed. Central bankers are seen, rightly or wrongly, as interfering where previously doing no harm was their credo and, worse still, implementing policies that potentially impact the income distribution, an area that has always been the province of government policies.

Several other questions are addressed in the book but I will consider one more here. Should central banks, as one central banker has alluded to, become more like weather forecasters? The weather forecasting analogy is misleading on several counts. First, weather forecasters are not required to meet a certain economic objective. Even if weather forecasting has undoubtedly improved in recent years, the horizon over which individuals make decisions conditional on the weather is often shorter than the one a central bank generally employs or financial markets and the public expects. Moreover, monetary policy is not exclusively reliant on the predictions of a single model, or even a multiplicity of models, but includes an important role for judgment. Models serve as a disciplining device. Otherwise, the alternative is for monetary policy decisions to be made on the basis of instinct alone. This might work from time to time but it is not a recipe for delivering consistently good monetary policy. I provide estimates of the evolution of inflation forecast disagreement for several economies to suggest that we are a long way from being able to replicate recent improvements in weather forecasting.

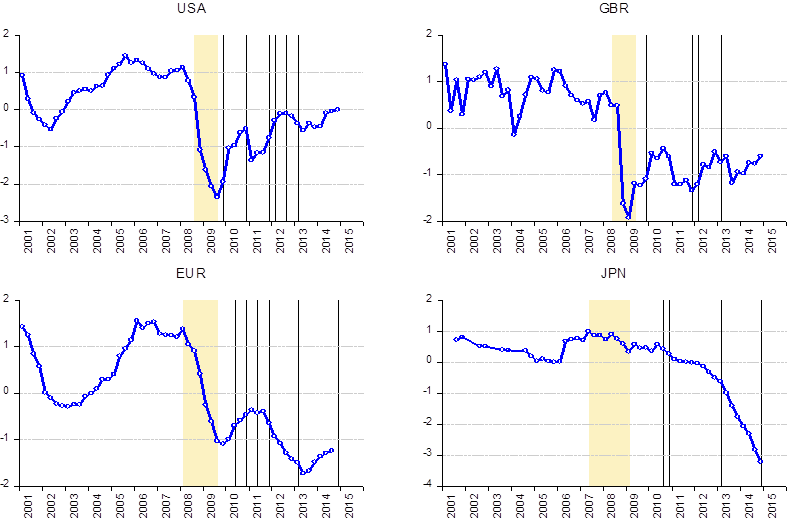

The institution of central banking is not broke and if it does not require fixing as such it is certainly in need of renovation. Repairing how and when central banks act in a future crisis is one place to start. It is essential to recognize that financial stability is part of central banking, but that central banks need not be the only institution with a stake in achieving that stability. Central banks did step into the breach to do some of the work other institutions could not or did not want to carry out. However, this is no substitute for revisiting the appropriate division responsibilities for governing monetary policy and financial system stability. As long as judgment plays a critical role in policy, as it must, there is a place for outsiders to get a better look inside the conduct of monetary policy. Trust, once lost, is difficult but not impossible to regain. However, as the Figure below suggests (from Chapter 5 in the book) only the Fed has managed to reverse the sharp loss of trust suffered in the aftermath of the crisis. We may, of course, disagree about how trust is measured but there is little debate that central banks have and continue to be under fire for some of their decisions over the past eventful decade.

Note: The estimates are based on the first principal component consisting of the inflation and real GDP growth forecast errors, the long-short interest rate spread, the VIX, the share of central bank assets to GDP, indicators of credit growth and the optimism content in central bank press releases. The online appendix contains more details. GBR is the United Kingdom, EUR is the Eurozone, and JPN is Japan. The shaded areas highlight the period of the GFC while the vertical lines indicate various forms of central bank interventions (i.e., various forms of unconventional monetary policies).

This post written by Pierre Siklos.

French-Hungarian, eh? Lots of bad ethnic tendencies there. On the other hand, it virtually guarantees excellent dinner conversation!

As if all this is not enough, the notion that simple rules can be followed flexibly leaving aside a role for the stability of the financial sector, has now been replaced by difficult questions about how to simultaneously manage inflation control and mitigate the risk of another financial crisis through macroprudential means. Decades after the politics were largely taken out of monetary policy, the situation has been reversed. Central bankers are seen, rightly or wrongly, as interfering where previously doing no harm was their credo and, worse still, implementing policies that potentially impact the income distribution, an area that has always been the province of government policies.

I think this point is well taken. If growth, inflation and interest rates are to be low, then by extension, asset prices are likely to be high and social inequality elevated. In addition, central banks will be complicit in the run up of major deficits and debts, with the prime example being Japan. The US is not immune either.

So, are we speaking of the incumbent pre-2007 monetary regime persisting with just a bad patch? Or are monetary conditions suffering the lingering but finite effects of a muted depression in the Great Recession, RR style? Or do we see a new and enduring regime driven principally by aging and a secular decline in birth rates in the OECD and China, as my Japan article suggests? These are rather important questions, because, depending on which regime you are in, a different fiscal and monetary policy is optimal and/or politically likely. For example, how do you impose fiscal discipline, say, in the Obamacare debate, if interest rates are low and expected to stay so, borrowing capacity is ample, and voters want more healthcare (pre-ex conditions coverage) without the willingness to pay for it (no mandate)?

In any event, thank you for the post, Pierre. I found it very interesting.