Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan, Professor and Instructional Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Houston.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC or Committee) raised the target range for the federal funds rate (FFR) by 3/4 percent (75 basis points) from 0.75 – 1.0 percent to 1.5 – 1.75 percent at its June 2022 meeting and projected a range between 3.25 and 3.5 percent by the end of 2022. While the statement “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate,” Chair Powell’s press conference, the minutes, subsequent remarks by FOMC members and the most recent inflation data make it clear that another 75 or even 100 basis point increase in July is virtually certain. This followed a 25 basis point increase from the effective lower bound (ELB) of 0.0 – 0.25 percent in its March meeting and a 50 basis point increase in its May meeting.

While there is widespread agreement that the Fed fell “behind the curve” by not raising rates quickly enough when inflation rose in 2021, there are two very different leading explanations. The “we didn’t know” explanation, advanced by Fed Chair Jerome Powell and other members of the FOMC, is that the Fed did not realize that inflation would rise so much in 2021 and, if they had, they would have raised rates in fall 2021 instead of spring 2022. The “they should have known” explanation, advanced most prominently by Larry Summers, is that the Fed should have known that inflation would rise and raised rates sooner.

Much of the discussion of the Fed being behind the curve depends on subjective analysis of when liftoff from the ELB should have occurred. In a new version of a paper that includes the June 2022 Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), “Policy Rules and Forward Guidance Following the Covid-19 Recession,” we use data from the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) from September 2020 to June 2022 to compare policy rule prescriptions with actual and FOMC projections of the FFR. This provides a precise definition of “behind the curve” as the difference between the FFR prescribed by the policy rule and the actual FFR.

The FOMC adopted a far-reaching Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in August 2020. The framework contains two major changes from the original 2012 statement. First, policy decisions will attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. Second, the FOMC will implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

At its September 2020 meeting, the Committee approved outcome-based forward guidance, saying that it expected to maintain the target range of the FFR at the ELB “until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessment of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

If the Fed had followed a policy rule using inflation and unemployment data from the FOMC’s quarterly SEP’s instead of the FOMC’s forward guidance, they could have avoided the pattern of falling behind the curve, pivot, and getting back on track that characterized Fed policy during 2021 and 2022. The rules prescribe liftoff from the ELB in 2021:Q2 or 2021:Q3 and a much smoother path of rate increases through the end of 2022 than that adopted/projected by the FOMC. Since the rules use data from the SEP rather than inflation and unemployment expectations, it makes the “we didn’t know” explanation irrelevant and the “they should have known” explanation unnecessary.

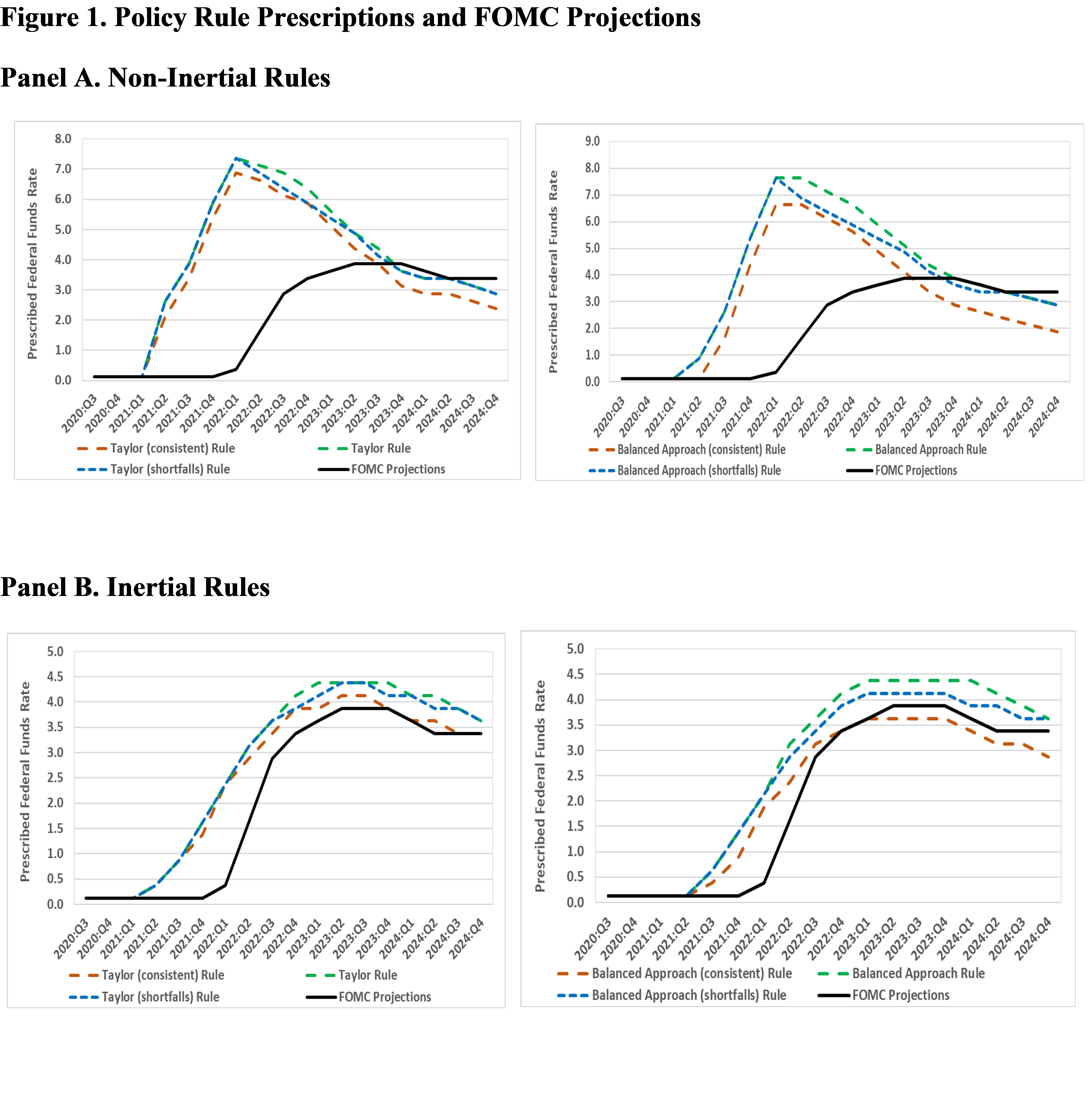

We consider six policy rules. The Taylor (1993) rule prescribes that the FFR equal the inflation rate plus 0.5 times the inflation gap, the difference between the inflation rate and the 2 percent inflation target, plus 1.0 times the unemployment gap, the difference between the rate of unemployment in the longer run and the realized unemployment rate, plus the neutral real interest rate. The balanced approach rule in Yellen (2012) raises the coefficient on the unemployment gap to 2.0 while maintaining the coefficient of 0.5 on the inflation gap. The Taylor and balanced approach (shortfalls) rules are identical to the original rules except that they do not prescribe a rise in the FFR when unemployment falls below longer-run unemployment.

Neither the original nor the shortfalls rules are consistent with the revised statement. We introduce two new rules in accord with the revised statement that we call the Taylor and balanced approach (consistent) rules. First, we replace the rate of unemployment in the longer run with the unemployment rate consistent with maximum employment and base FFR prescriptions on shortfalls instead of deviations. Second, if inflation rises above 2 percent, the rule is amended to allow it to equal the inflation rate “moderately” above 2 percent that the FOMC is willing to tolerate “for some time” before raising rates in order to bring inflation down to the 2 percent target.

Starting with the original Taylor rule, normative policy rule prescriptions are typically “non-inertial” as the prescribed FFR depends on the realized values of the right-hand-side variables. Following Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999), estimated Taylor-type rules are typically “inertial” to incorporate slow adjustment of the actual FFR to changes in the prescribed FFR. Policy rule forward guidance, however, involves normative policy rule prescriptions that need to be inertial when inflation rises quickly in order to be in accord with the FOMC’s desire to smooth out large rate increases over time. We follow Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019) and specify inertial rules with a coefficient of 0.85 on the lagged FFR and 0.15 on the target level of the FFR specified by the corresponding non-inertial rule.

The figure depicts the actual FFR for September 2020 to June 2022 and the projected FFR for September 2022 to December 2024 from the June 2022 SEP. Panels A and B illustrate prescriptions from the non-inertial rules. Five of the six rules prescribe liftoff from the ELB in 2021:Q2, three quarters earlier than the actual liftoff. All of the non-inertial rules prescribe unrealistic jumps in the FFR. For the Taylor rules, there are prescribed jumps of at least 200 basis points in 2021:Q2 and 2021:Q4 and, for the balanced approach rules, there is a 275 basis point jump in 2021:Q4. The prescribed rate increases peak in 2022 and are mostly 50 basis points below the FOMC projections at the end of 2024.

Panels C and D show prescriptions from the inertial rules. The prescribed liftoff from the ELB is slightly later than with the non-inertial rules, 2021:Q2 for the Taylor rules and 2021:Q3 for the balanced approach rules. The inertial rules prescribe much more realistic paths for the FFR than the non-inertial rules. Most of the prescribed rate increases are 25 basis points and there are no increases greater than 50 basis points. The prescribed FFR’s with the inertial rules continue to increase but much more slowly than those with the non-inertial rules. They peak in 2023 and are mostly 25 basis points above the FOMC projections at the end of 2024.

We focus on the balanced approach (consistent) rule through March 2022 because it is in accord with the Fed’s preference for balanced approach rules and the revised statement. In March 2022, the FFR was 1.5 percent below the policy rule prescriptions. By June 2022, high inflation had become the Fed’s priority. It had met its employment goals, clearly exceeded its inflation goals, and was not going to raise interest rates if unemployment rose from 3.6 percent to its longer-run value of 4.0 percent. We therefore shift focus to the balanced approach (shortfalls) rule. By June 2022, the gap fell to 1.25 percent and, by December 2022, it is projected to further narrow to 0.5 percent. The FOMC could eliminate the gap by the end of 2022 by implementing 50, rather than 25, basis point rate increases in November and December 2022.

From the policy rule perspective, the FOMC fell behind the curve by following its forward guidance and delaying rate increases for too long. If the FOMC had followed policy rule forward guidance with an inertial rule, it would not have fallen behind the curve in 2021, placing it in a much better position to respond when inflation rose and avoiding the series of large rate increases in 2022. To get back on track by the end of 2022, the FOMC would need one 25, four 50, and two 75 basis point rate increases. By following the policy rules, it would still need four 50 basis point rate increases but would not need any 75 basis point increases.

This post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2021/08/26/its-time-fed-rethink-quantitative-easing/

August 26, 2021

It’s time for the Fed to rethink quantitative easing

The Federal Reserve building in D.C. (Chris Wattie/Reuters)

By Lawrence H. Summers – Washington Post

The American experience in Vietnam and Afghanistan teaches an important lesson. Making policy incrementally — focusing on adjusting the current policy path to avoid near-term pain, rather than stepping back and assessing whether the current state of affairs makes sense — can lead to terrible outcomes. Indeed, this was the central lesson Daniel Ellsberg drew from the Pentagon Papers.

The same principle applies in economic policy. As the Federal Reserve meets virtually for its annual Jackson Hole retreat, it should, but probably won’t, step back and reassess its continuing quantitative easing policy, which has gone on for too long. The current policy is explicable as the result of a month-by-month decision-making process, following the urgently needed steps the Fed took at the beginning of the coronavirus crisis. But viewed from the perspective of current economic conditions, it cannot be justified and presents its own danger.

Quantitative easing is a policy of creating money in the form of providing interest-paying reserves to banks and buying up Treasury bonds and other government-guaranteed securities. This step was clearly warranted when bond markets were illiquid, highly volatile and in danger of collapse — the case in 2008 and 2009 and again in the covid spring of 2020. As with any highly potent medicine, managing its withdrawal is delicate. But the beginning of wisdom is seeing that the quantitative easing prescription makes little sense today….

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/19/opinion/inflation-economy-supply-chain.html

November 19, 2021

Wonking Out: Going beyond the inflation headlines

By Paul Krugman

Early this year some prominent economists warned that President Biden’s American Rescue Plan — the bill that sent out those $1,400 checks — might be inflationary. People like Larry Summers, who was Barack Obama’s top economist, and Olivier Blanchard, a former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, aren’t unthinking deficit hawks. On the contrary, before Covid hit, Summers advocated sustained deficit spending to fight economic weakness, and Blanchard was an important critic of fiscal austerity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

But Summers, Blanchard and others argued that the rescue plan, which would amount to around 8 percent of gross domestic product, was too big, that it would cause overall demand to grow much faster than supply and hence cause prices to soar. And sure enough, inflation has hit its highest level since 1990. It’s understandable that Team Inflation wants to take a victory lap.

When you look beyond the headline number, however, you see a story quite different from what Summers, Blanchard et al. were predicting. And given the actual inflation story, calls for the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to cool off the economy look premature at best.

First, overall demand hasn’t actually grown all that fast. Real final domestic demand (“final” means excluding changes in inventories) is 3.8 percent higher than it was two years ago, in an economy whose capacity normally expands about 2 percent a year:

https://static01.nyt.com/images/2021/11/19/opinion/krugman191121_1/krugman191121_1-jumbo.png?quality=75&auto=webp

Not that much of a demand surge….

Inflation driven by temporary supply chain disruptions are not a real problem and The Fed SHOULD always be way behind the curve on those. Yes they can be scary for the general public, but they have little real effects in the long term. The problem with the kind of overreaction we are currently seeing is that this type of inflation already has its own automatic brakes baked in. Those automatic brakes on the supply side are the strong (profit) incentives to fix supplies – and on the demand side that when prices increase more than wages, consumers are forced to reduce demand (even if they spend the same amount of money). So supply disruption inflation will tip over such that high price increases are followed by moderate to high price decreases (as we again reach back to the prices dictated by an equilibrium between production cost, competition and consumer demand). Whatever is done by The Fed is likely to have effects that are delayed and, therefore, will hit at the exact wrong time. If they follow through with the current plan there is a fairly good chance that they will cause completely unnecessary harm to the ignored part of their mandate (employment).

It’s interesting that the inflation hawks never seem to explain how higher interest rates in 2021 would have replaced Russian oil, produced more new and used cars, shipped more Ukrainian wheat and made over 100 million MAGA-hatters get vaccinated. If you can’t explain that, you’re just blowing smoke and your only real solution is to make low wage workers even poorer.

Russian oil production is down only marginally, cc 0.5 mbpd, or about 0.5% of global consumption.

Oil production has not been hit by this war? So WTF have you been babbling about for the past 3 months? Your opinions have always struck me as malleable.

Russian oil production is recovering.

The argument is based on the premise that the Fed cares about inflation. Sure, they have a bunch of fresh MBA grads churning out reports which they twist and manipulate to show low inflation, but the real goal of the Fed is to keep the bubbles inflating. The Fed and Wall Street love their bubbles. Everyone gets rich in bubbles…well, the rich get richer in any case, which is all that matters.

Consider this seriously. Why should there be any inflation in the first place? According to many economic models there should be deflation as technology and mass production lower the prices of goods and services. But deflation means lower or stagnant wages as well as declining GDP. That looks terrible even if it is, in fine, a good thing. The crux of the problem is debt. America is too indebted to allow for stable prices or deflation. So the Fed, Wall Street and Washington have created the myth that a little inflation is good and necessary. Deflation, they say, is evil because…well…”Look at the Great Depression! Deflation!” This ignores the fact that inflation, a bubble, created the Great Depression and deflation was an inevitable result of the crash and depression, not a cause.

Burn up 50 years of real wealth (food, oil, minerals, labor) in a decade or so and you have to pay the price somewhere down the line. So screw the Fed and their policies. They will inflate to keep the DJIA rising. They will inflate to keep debt manageable while pretending that the debt bubble is not a problem either.

But spare me the nonsense about the Fed being too incompetent. It’s a straw man debate. And all the rest of the graphs and theories are just bullshit, lipstick on a pig, if you will.

Expat: Having spent some time at the Fed, I can say that the economists are not typically a “MBA”; they are typically PhDs in economics. The RA’s are sometimes MBAs but more often BA’s, BSc’s and MA’s.

Besides getting their degrees wrong, this has to be the most insulting and incorrect comment I have ever read.

Expat,

Aside from not knowing who works at the Fed, which Menzie has accurately described. you really seem to be quite out of it.

One can argue about whether they are folllowing their own rules or should be, the main focus of the guest post, but they are definitely engaging in anti-inflationary policy now. Their sharp increases in interest rates, with more likely to come, have brought the DJIA down quite a bit from its highs of months ago, and the housing market has been sharply slowed, with prices almost certainly halting their recent increases, if what we see in the near term is more likely to be a slowdown in sales than an outright decline of prices. But, sorry, they are not pumping bubbles right now, quite clearly the opposite.

Where did you come up with such delusional nonsense?

Sorry, you are all wrong. First of all, my comment about MBA’s was hyperbole, which, if you did not figure that out, says more about your narrrow-minded, rigid approach to debate than my “errors”. Second. Menzie, who is apparently the only one here who has worked at the Fed, did not say that no MBA’s worked there; he said it was more PhD’s but admits that MBA’s work there.

So instead of discussing my premise, which is that Fed policy is dictated or remotely influenced by the Wall Street and the White House, you shit all over me because you are desperate…for what, I don’t know. Perhaps suck up to the authors and mods? Has anyone bothered to follow up on policy and comments from the Fed since this post was made? What is Wall Street’s reaction? Where has the DJIA gone since then? Where have rates gone? Do you still believe the Fed will raise rates to or above the level of inflation? Sure doesn’t look like it to me. Instead, everyone is now pretending that inflation was transitory, that rates don’t really need to go up, and everything will be fine.

So now tell me how much it costs to fill your shopping cart, fill your car, pay your kid’s tuition, visit a hospital or go to a ballgame. Once you have done all that, you can come back and continue to hurl your childish epithets at me.

Well, this is a rather damning analysis. This line is just a killer: “there are prescribed jumps of at least 200 basis points in 2021:Q2 and 2021:Q4 and, for the balanced approach rules, there is a 275 basis point jump in 2021:Q4.”

Wow! Two quarters averaging 230+ basis points increase and 700 basis points over one year! It speaks to just how loose monetary policy was. Clearly, this must have shocked the authors, who then felt compelled to offer a diluted version.

I think the ‘Inertial Rules’ model is probably too little, too late, but let’s go with that. By that model, the FFR should be 240 basis points higher than it is, so even a 100 bp increase is way too small.

Finally, the analysis suggests that there is a ‘Crazy Land’ faction at the Fed, a group of economists who felt that a 40% increase in M2 was suicidal. I have often consulted for companies in trouble, and I can assure you, the necessary steps to remedy the situation were always apparent within the organization, sometimes years in advance. I don’t think you’d have to speak to more than four Fed economists to find the Crazy Land faction. There are plenty of economists at the Fed who can perform the analysis provided here by Papell and Prodan. They had a pretty good idea of what was coming down the pike.

It’s a pity they did not speak up. There will be a high price to be paid, not only in the US, but across the globe.

“Clearly, this must have shocked the authors, who then felt compelled to offer a diluted version. ”

Aside from the fact that “Clearly” and “must have” amount to quibbling over whether they did, how the heck would you know? They said what they said, and you think hey watered it down? They wrote it down. Different thing.

Your analysis? We keep hearing about your analysis, without ever seeing any. You haven’t written it down.

This whole “‘I’m an expert” routine is getting tired. You’re a consultant. That doesn’t make you an expert. Show your work.

Well he has been pushing the Quantity Theory of Money as some advanced modern macroeconomic model even though even the monetarist abandoned this nonsense back in the 1970’s.

Duckie, P&P write:

The inertial rules prescribe much more realistic paths for the FFR than the non-inertial rules. Most of the prescribed rate increases are 25 basis points and there are no increases greater than 50 basis points. The prescribed FFR’s with the inertial rules continue to increase but much more slowly than those with the non-inertial rules. They peak in 2023 and are mostly 25 basis points above the FOMC projections at the end of 2024.

So, if you go with the non-inertial rules, then the FFR should be set to 7% now. That’s what Panel A says, and that’s the result of just putting the numbers through the model.

P&P don’t want to climb fully on board with this because it would imply a 550 basis point hike right now. Can you imagine that? Wow! That’s end-of-the-world sort of stuff.

So, P&P take the view of gradual, but somewhat more aggressive, rate hikes over time. But one conclusion is inescapable. Inflation must remain higher for longer using inertial rules than using non-inertial rules, if for no other reason than because non-inertial rules yield a much higher FFR until about Q2 2023. To chose one specific date: By NI rules, in Q1 2022, the FFR should have been 7%; by inertial rules, it should have been around 2.5%. That’s a big difference, and inflation should be materially higher in the latter than in the former.

So Panel A and Panel B are not, let me repeat, not the same policy advice. Panel A is far more aggressive, and that’s what a simple mathematical calculation yields. Panel B, the Inertial Rules, exist because P&P are thinking that they can’t simply recommend the plain vanilla option, which is also the nuclear option.

I can understand that, and I would have done the same thing. But that comes down to practical and political considerations. P&P’s advice can’t simply boil down to “Push the Red Button”.

I would note my interpretation is not a matter of ‘expertise’, but rather reading the graph. My expertise, as it applies here, is giving formal advice to clients, and sometimes conditions do not permit you to put the plain vanilla option front and center.

Steven Kopits: First, the Taylor rule can be taken two ways — the first is as a positive statement on how central banks operate by changing their policy rate, and second as a normative statement as to *how* they should manage the policy rate. The inertial rule is more “realistic” in the sense that no central bank goes around willy-nilly moving around the policy rate week by week, as might be implied if one used the non-inertial rule. Financial markets would probably be going crazy with that kind of uncertainty. That’s why P&P don’t “go” with the non-inertial rule. (I’m guessing here, but since I’ve know the first “P” in P&P for about 30 years, I think I have some insight.)

Yes, I understand what you’re saying Menzie, and I agree.

However, the difference between Panel A, in essence a recommendation unmoored to real world considerations; and Panel B, policy delimited by political and market realities, is a measure of the mess the Fed has made. Panel A and Panel B are not the same policy in any measure which matters in, say, political terms.

Policy following Panel B may lead to inflation which is unacceptably high for an extended period, certainly through 2023. Indeed, Panel B suggests that inflation and recession at the same time, a ‘Nor’wester’ in my terms, may in fact be possible. Following Panel B, it may actually be probable.

In any event, P&P need an inertial model because Fed policy has been so distorted that following some version of the Taylor Rule per Panel A is politically unworkable.

Steven Kopits: I am not a Taylor rule expert, but I am pretty sure no central bank in the world that has its own currency and is on a less than perfect peg runs a non-inertial Taylor rule.

Well, they don’t have a choice in this case, do they? So that means you’re carrying a prolonged bout of inflation, if P&P have their math right.

Well, I would not be surprised if, say, the Turkish or Argentine central banks had raised interest rates in decidedly un-inertial ways in the past.

Did you bother to read the entire post? If so, you clearly did not understand it. No one is suggesting the FED should have raised interest rates by 7% except you. And your repeating this stupid statement does not enhance its “credibility”.

“I would note my interpretation is not a matter of ‘expertise’, but rather reading the graph.” Well you are misintepreting the graph as your expertise is ZERO. Any one who is your client is a fool.

That’s what the math says. That it should even be an issue is a measure of just how distorted Fed policy has become.

“Clearly, this must have shocked the authors, who then felt compelled to offer a diluted version. ”

Aside from the fact that “Clearly” and “must have” amount to quibbling over whether they did, how the heck would you know? They said what they said, and you think hey watered it down? They wrote it down. Different thing.

Your analysis? We keep hearing about your analysis, without ever seeing any. You haven’t written it down.

This whole “‘I’m an expert” routine is getting tired. You’re a consultant. That doesn’t make you an expert. Show your work.

Stevie using his advanced Quantity Theory of Money forecasted that inflation would be around 40%. How did that work out?

“Two quarters averaging 230+ basis points increase and 700 basis points over one year! It speaks to just how loose monetary policy was.”

Whoever wrote this BS stopped reading after he looked at the graph labeled non-inertial rules and failed to read this:

“Panels C and D show prescriptions from the inertial rules. The prescribed liftoff from the ELB is slightly later than with the non-inertial rules, 2021:Q2 for the Taylor rules and 2021:Q3 for the balanced approach rules. The inertial rules prescribe much more realistic paths for the FFR than the non-inertial rules. Most of the prescribed rate increases are 25 basis points and there are no increases greater than 50 basis points. The prescribed FFR’s with the inertial rules continue to increase but much more slowly than those with the non-inertial rules. They peak in 2023 and are mostly 25 basis points above the FOMC projections at the end of 2024.”

Of course, Stevie fishes for the dramatic even though he never has a clue what any of these words even means. After all he actually thinks the Quantity Theory of Money is modern advanced macroeconomics!

Considering the state of the labor market and the fact that the Fed has little control over worldwide supply disruptions from a major war and deadly virus, its not at all clear that the Fed acted too slow or failed in anyway.

If policy rules require you to throw people out of work because a war is affecting oil and food supplies, you might want reexamine what the goal is behind those rules.

Good point. John Taylor wrote the seminal paper back in 1993 after all. The world now is a very different place.

Then you’re saying 9.1% inflation is the best of all possible worlds. Well, see how that notion sells among your friends and relatives.

What a stupid question. Of course you are one stupid fellow so hey!

Let me repeat this, because you seem to be having trouble grasping the issue, pgl.

Jdubs writes: “Considering the state of the labor market and the fact that the Fed has little control over worldwide supply disruptions from a major war and deadly virus, its not at all clear that the Fed acted too slow or failed in anyway.”

Well, both P&P and Benn Steil / Benjamin Della Rocca make it painfully clear that the Fed, in fact, acted much too late, and left the taps on a solid year longer than it should have. Clearly, none of P&P or Steil/Della Rocca believes that 9.1% is the ‘best of all worlds’.

I hope you realize you are using words and numbers that you do not understand. Which is why your hyperbole is always hysterical.

Do you even have a clue what “estimated Taylor-type rules are typically “inertial” to incorporate slow adjustment of the actual FFR to changes in the prescribed FFR.”?

Of course not!

Let’s take this a little farther.

According to the Inertial Rule, the FFR should be between 4.0-4.5% for most of the next two years. Historically, 30 year mortgages have been 2-3% more than the FFR. So that would put 30 year mortgages in the 6-7% range for the next two years.

That would be a prolonged period of brutality in the real estate market of the sort we have not seen since the early 1980s.

And this.

This is the analysis pgl should have made, but alas, did not. It speaks to the difference between a depression and a suppression.

https://www.cfr.org/blog/how-fed-bond-binge-predictably-stoked-inflation

Indeed, Argentina raised its 7 day LELIQ rate by 250 basis points on April 13th and another 300 basis points on June 16th. These are decidedly non-inertial interest rate hikes, at least as defined in US terms.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-13/argentina-raises-key-rate-to-47-as-inflation-hits-20-year-high#xj4y7vzkg

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-06-16/argentina-raises-benchmark-rate-to-52-as-inflation-stays-hot#xj4y7vzkg

Steven Kopits: Well, if you’re in a balance of payments crisis, sometimes you do move around your interest rate overnight (the Russians did in February). However, if you look at a time series for the Leliq rate, you’ll see that there are long periods of smoothed interest rates, and even as it raised interest rates recently, it was in a fairly smooth path.

https://tradingeconomics.com/argentina/interest-rate

Truthfully, why do you write about things you barely know anything about (and I’m not just talking about confidence intervals).

Menzie, you wrote:

“I am not a Taylor rule expert, but I am pretty sure no central bank in the world that has its own currency and is on a less than perfect peg runs a non-inertial Taylor rule.”

That’s clearly not true. During periods of financial stress, notably during period of high inflation, we can see that central banks do in fact raise interest rates by non-inertial amounts. These may be exceptional cases, but at 9.1% inflation, by US standards, we are in an exceptional case.

Steven Kopits: I would still characterize the Argentine conduct with respect to the policy rate as inertial. No central bank routinely moves their policy rate day by day as new information comes in. If you ever tried to estimate a Taylor rule yourself with say monthly data (as I have), a non-inertial rule gives you interest rates bouncing around month by month. Imagine doing it with weekly data. Then imagine doing it with daily data.

Yes, if you have a balance of payments crisis, then you deviate. But in the rest of the time, even in Argentina, you smooth.

Let’s put it another way. There is precedent for a central bank to raise interest rates by 300 basis points in one go, which is exactly what Panel A is showing. Now, the US is not Argentina, and the FFR is 1.58%, not 52%. But, yes, there is precedent for 300 bp interest rate hikes, strictly speaking.