A recent NYT article highlighted the fact that international competitiveness (as defined by macroeconomists) depends on not just the nominal exchange rate, but also relative price levels. From Inflation in China May Limit U.S. Trade Deficit by Keith Bradsher:

Inflation is starting to slow China’s mighty export machine, as buyers from Western multinational companies balk at higher prices and have cut back their planned spring shipments across the Pacific.

It’s useful to recall that one definition of the (log) real value of a currency (defined as number of foreign units of real goods required to obtain one single unit of domestic goods, so up is appreciation) is:

r ≡ e + p – p*

where e is the log value of the currency (number of foreign currency units to obtain one single unit of home currency), p and p* are the log domestic and foreign price levels.

As Chinese inflation (4.6% y/y in December [0]) exceeds US (or rest-of-world) inflation, then the Chinese real exchange rate appreciates (r rises). It’s important to keep in mind the magnitude of these effects, though. To me, RMB appreciation is still trending along the same path it was before the financial crisis.

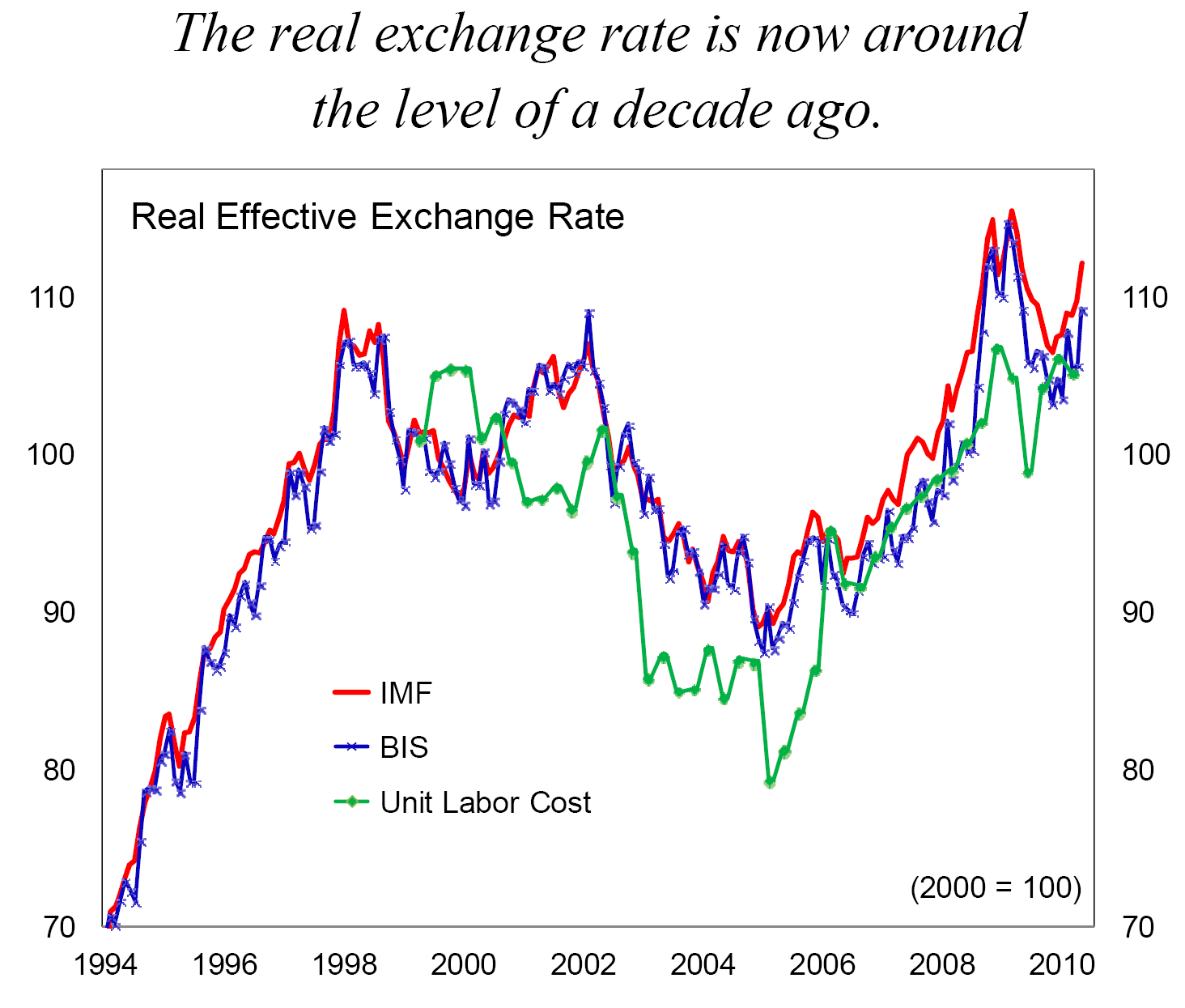

Figure 1: Log real value of trade weighed CNY, broad basket. Source: BIS, accessed 2/2/2011.

Here’s the caveat. The BIS (as well as IMF) indices are CPI deflated. As I’ve discussed elsewhere [1] [2], there are actually many definitions of real exchange rates, which depend upon the deflator used. In the article, Bradsher is actually referring to several related versions, including one deflated by manufactured exports prices, and by wages. Clearly, these two are linked — the higher the wages, the higher the price of the finished good, assuming a constant price-cost margin.

Actually, once one writes out the expression for pricing by a monopolistically competitive firm, one sees the price is a function of the price-cost markup (itself a function of demand elasticities) and unit labor costs — the wage rate divided by productivity. This suggests a more appropriate deflator for assessing competitiveness is the unit labor cost deflated real exchange rate.

Source: IMF Article IV report on China, p.19.

Thus, in focusing on wage movements (which do seem quite dramatic), Bradsher is assuming productivity trends are not too marked relative to wage changes (and further the scope for compression of price-cost margins is limited, which seems reasonable — although see [3]). However, unit labor costs have in the past diverged from CPI.

If indeed wages are rising rapidly due to exhaustion of excess labor supply in the coastal regions, then this would be an important milestone in rebalancing the Chinese economy [4].

Update: 11am Pacific Free Exchange has an interesting guest post, citing this paper, which examines the impact of yuan revaluation on US inflation (so looking at pass-through into overall prices, rather than into import prices, as I examined in this post. One interesting aspect is that it focuses on overall US import price index as a function of yuan changes. It’s not the regression I would’ve run, but heck, as my teacher, George Akerlof often said (and maybe still says): “Nothing stops me…”.

“Inflation is starting to slow China’s mighty export machine, as buyers from Western multinational companies balk at higher prices and have cut back their planned spring shipments across the Pacific.”

If I understand correctly, China still has vast untapped unemployed or underemployed labor reserves. Apparently, they are unable to incorporate the unemployed labor into the economy fast enough. The question, it seems to me, is whether it is easier to let inflation adjust the real exchange rate and cure a temporary excess demand, or to revalue the currency. It may depend on whether it would be easier to reverse the change in the real exchange rate through deflation or through devaluation if, in future, they move from excess demand to deficient demand. (They had deflation recently, and handled it fairly well, whereas a deliberate devaluation might bring strong external objections.)

“Thus, in focusing on wage movements (which do seem quite dramatic), Bradsher is assuming productivity trends are not too marked relative to wage changes”

This might be a serious mistake for longer-term comparisons.

He has another paper that examines the effect of Chinese import on US inflation

“The effect of low-wage import competition on U.S. inflationary pressure,” Journal of Monetary Economics, May 2010

If you haven’t already read it, the Feb 1st China Financial Markets newsletter from Pettis has a very interesting discussion on the subject. Excerpt below:

I wish I could just just link to it, but he asks it not to be reproduced. I highly recommend subscribing to it if you have access to it for no cost as an academic.

MorallyBankrupt: Thanks. I don’t have access, but this is a good point, and perfectly clear once one knows the various definitions of “international competitiveness”.

Of course, if administrative credit controls tighten so the effective interest rate rises, then unit costs should rise.