Last week ECB President Mario Draghi revealed that the European Central Bank has been considering large-scale asset purchases as a tool to prevent European inflation from falling too far below the ECB’s target rate of 2%. What is the evidence for the effectiveness of these policies, and are there any risks?

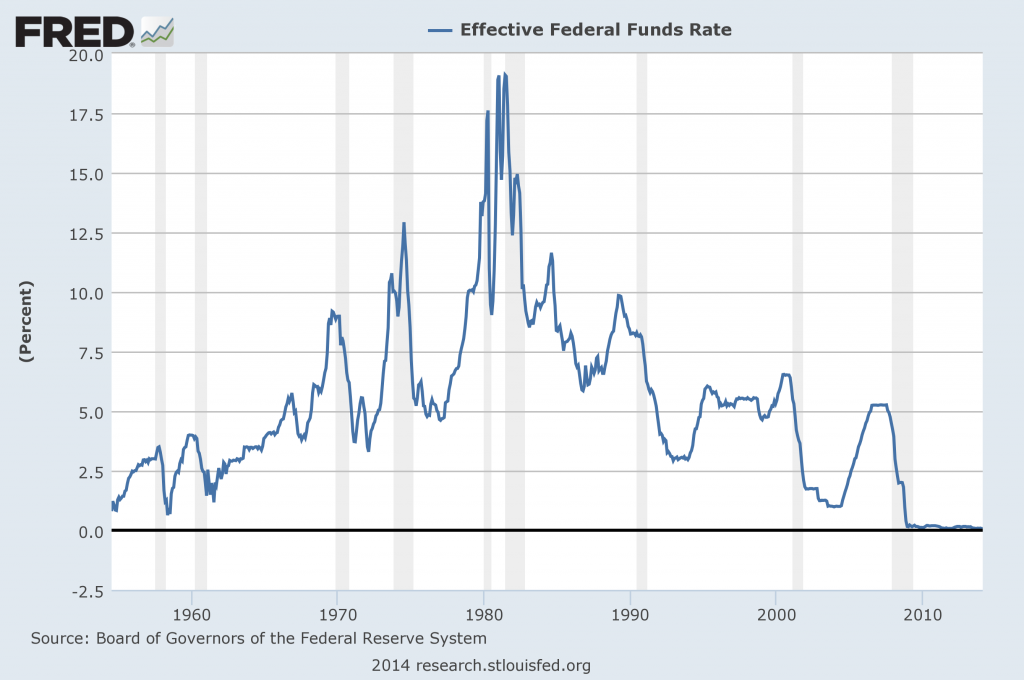

Historically, when the U.S. economy went into recession, the Federal Reserve would lower interest rates through its control of the fed funds rate, an interest rate on overnight loans between banks. Lower interest rates helped stimulate demand for items such as housing and autos and raise asset prices more generally, all of which would help spur economic recovery. But that tool is not available to the Fed in today’s environment in which the fed funds rate is essentially already zero.

Source: FRED.

The Fed has adopted less conventional policies in the current environment by buying assets in huge volumes (large-scale asset purchases) and by indicating its intention to keep the fed funds rate low even after the economy was well into recovery (forward guidance). Although the trillions of dollars involved in LSAP may seem dramatic, the reserves that the Fed created to pay for these operations are for the most part still just sitting idle on banks’ balance sheets at the end of each day. Since those reserves earn interest when left with the Fed overnight, I think the best way to think of them is as overnight loans from banks to the Fed. If all the Fed did with these operations was buy short-term Treasury bills, essentially LSAP would just swap one short-term liability of the U.S. government (Treasury bills) for another very similar short-term liability of the U.S. government (reserves held in accounts with the Fed). Such a swap would be unlikely to change anything that matters regardless of how many trillions of dollars were involved.

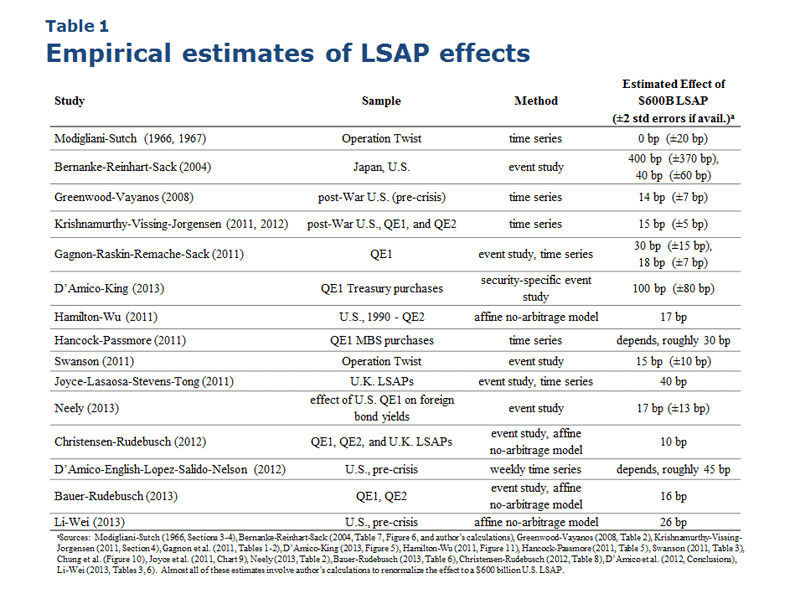

For this reason, the Fed has been buying not Treasury bills but instead longer-maturity Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities. Taking a huge volume of these assets out of private hands and replacing them with overnight government liabilities could perhaps affect the yields on long-term Treasuries and MBS. An early analysis by Modigliani and Sutch (1966) found little evidence of an effect on interest rates of “Operation Twist” in 1961 when the Treasury tried to issue more short-term and fewer long-term securities, though a more detailed analysis of that episode by Swanson (2011) concluded that Operation Twist did have a measurable effect on yields. A number of other studies have looked at the variation over time in the maturity structure of U.S. Treasury debt and have found statistically significant correlations between the maturity structure and relative yields; see for example Kuttner (2006), Gagnon, et. al. (2011), Greenwood and Vayanos (2013), Doh (2010), and Hamilton and Wu (2012) (ungated version here).

Another approach is to look at what happened to yields on days when the Fed announced changes in LSAP that caught the markets by surprise. For example, when the Fed first announced the scope of its intended large-scale asset purchases on March 18, 2009, the yield on 10-year Treasuries fell 51 basis points. Last May, when the Fed indicated it was considering slowing the pace of asset purchases, yields went back up. Analyses of events like these provide fairly convincing evidence that market yields react to Fed announcements of changes in its LSAP or forward guidance.

Source: Williams (2013).

A new paper by Rogers, Scotti and Wright (2014) reviews and updates evidence from the experience of the U.S., U.K., Europe, and Japan, and concludes, like most of the studies summarized in the table above, that LSAP and forward guidance are potentially effective policies for easing financial conditions when the short-term interest rate is already near zero.

Another new study by Hayashi and Koeda provides further evidence looking at the data in a completely different way. They note that during episodes in which Japan’s short rate was near zero, an increase in the level of excess reserves in month t tended to be followed by a higher level of output in month t+1.

There is thus considerable evidence that these unconventional monetary policy measures have some modest potential to help stimulate a struggling economy. Less clear is what risks may be associated with unconventional monetary policy. If we think of LSAP as primarily a shortening of the maturity structure of outstanding government debt, replacing long-term Treasury bonds with overnight liabilities of the central bank, it’s clear that one would not want to expect too much from such measures. Assuming though there are some benefits for a struggling economy of converting government debt to shorter-term liabilities, why might the Treasury be reluctant to shorten its maturity structure? The answer is fairly obvious. Although there might be plenty of demand for short-term obligations of the U.S. government right now, will that still be the case one or two years down the road? If the Treasury was forced into a situation of borrowing in a future setting in which the huge daily auction of Treasuries turned out to be undersubscribed, the result could be a sharp spike in interest rates and substantial financial instability.

How are things different when the government’s short-term liabilities are in the form of overnight deposits with the Federal Reserve? One important point to note is that although an individual bank can always get rid of reserves it doesn’t want by buying some alternative asset, in doing so those reserves don’t disappear from the system, but are instead simply passed on to another bank from whose customer the first bank purchased the asset. Some bank will end up holding the reserves whether or not anybody actually wants them. In this sense, the Fed can always be sure that someone will lend to them overnight, whereas the Treasury cannot.

If demand for reserves is less than the supply, it’s not the supply of reserves that has to change, but instead the change has to come in terms of the price on alternative assets. For example, if assets denominated in foreign currency look more attractive than low-yielding deposits with the Fed, the dollar would have to decline sufficiently until one dollar would buy so little in the way of foreign assets that it no longer is attractive to try to do so. How far would that be? To adapt President Draghi’s famous phrase, “whatever it takes.” If banks are holding trillions more in reserves than they want, I could imagine this adjustment in items such as the exchange rate and commodity prices being rapid and chaotic.

Although the mechanics of a flight from unwanted reserves would work differently from those for an undersubscribed Treasury option, it seems to me that the economic fundamentals are the same. When faced with such a situation, there would be nothing the Treasury or the Fed could do to avoid a spike in interest rates and a potentially very disruptive financial situation if lenders are no longer willing to continue to roll over what has effectively become a huge volume of overnight government debt.

It is of course inappropriate to be paralyzed by fear of such a scenario at the present moment, when interest rates and inflation are so low; any such problems will not arise until well into the future. But I also do not think it is inappropriate to dismiss these considerations entirely, particularly if we take the view (as I do) that the benefits of additional LSAP are also likely to be fairly modest. In the case of Europe, the ECB is missing its inflation target by a sufficiently large margin that further action seems to be warranted. But in the case of the United States, I think the current course signaled by the Federal Reserve– that growth of its balance sheet will end by the end of this year– is the correct one.

Reserve Credit at a Federal Reserve Bank is NOT a liability of the U.S. government; it is a liability of the owners of the Reserve Bank: the member banks of that district.

Since Reserve Credit is almost entirely held by member banks, the net balance between indirect liability and direct assets represents lending between one bank and the remaining banks in its district.

Avante Guard: We are talking here about reserve deposits, not reserve credit. Reserve deposits are a liability of the Federal Reserve on which the Fed pays interest. Loans made by the Fed to banks are an asset of the Federal Reserve on which the Fed receives interest.

Real estate markets are beginning to look quite frothy again. Here in Princeton, properties are again gaining many offers with agreed prices well above the ask. We see a similar bubble-like tendency in Miami, where the collapsed market is again beginning to look hot.

While easy money may arguably help increase output, it again seems to be creating bubbles, certainly in real estate and very possibly in capital markets. Thus, the impact of such initiatives must be considered not only against inflation rates, but also with respect to growing asset bubbles.

Unconventional monetary policy has unambiguously exploded the wealth and income gap. Progressives used to be concerned about those gaps.

I’ll concede that printing vast sums of money even after the crisis has had modest tonic effects on GDP and employment, but at what cost?

Fed heads have begun to consider risks to financial stability, but what about social stability?

1. The risk you discuss requires other assets to be more desired than the dollar. I can see how adjustment might be chaotic and rapid when that has been achieved but I think you’re assuming a step in there, that somehow and someway these other assets, meaning other currency in essence, is bang all of a sudden that fungible with the dollar and that happens without anyone being aware. And that fungibility process seems to assume a sort of runaway ignorance on the part of the Fed. I agree it’s a risk but looking at the world, we have the same question we’ve had since 2007: into what else? The Euro? Give me a break? The RMB? When the speculation is that currency is more not less likely for a messy period? The British pound? The Brazilian Real? The Israeli Shekel?

2. I would love to know the Fed’s own interpretation of the effects of shortening maturities. And by that I mean an unvarnished account, not a purely technical analysis. I would love to know how much emphasis they place on confidence effects, meaning a sort of counter-factual belief that if “we” don’t do x, then y would happen and y would be bad.

hang on there a sec.

I think you are conflating a couple of different things. A sudden shift in the demand for reserves (lower), a sudden shift in the demand for govt debt (lower), or a sudden shift in the demand for foreign assets (dollar fall) are all a result of higher inflation expectations or higher real yields on other assets. That would be great news, if true, but a sudden shift in inflation expectations fundamentally means that the market has lost confidence in the Fed’s ability to manage inflation.

The Fed has tamped inflation expectations associated with QE and unconventional policy by promising that any changes to the monetary base are temporary. Saying the Fed has lost the ability to unwind its balance sheet smoothly, is the same thing as saying the change to the monetary base is less permanent than we thought, which is the same thing as saying the Fed’s 2% inflation target is less credible than it is now. Saying that treasury rates are spiking (or the dollar crashing) is saying inflation expectations have become unanchored.

The only way any of these bad things happen is if the Fed loses credibility. Instead of discussing spooky chaotic things, we should be discussing the best way for the Fed to maintain credibility during its exit strategy. Discretionary monetary policy seems particularly dangerous to me.

With a rules based approach, perhaps inflation would end up running a bit higher or lower during the exit, but at least the market could better anticipate how much and for how long, because it could anticipate the rate of asset draw-down given incoming data. Any deviations between actual and expected inflation are short to medium term. Perhaps the exit is too fast or too slow, but we know roughly when things will return to normal.

With a discretionary approach, the how-much-for-how-long is much less certain. And then you have the possibility of no change whatsoever (fed gets really behind the curve) and a small but nonzero probability of inflation getting out of control. There is your chaotic interest rate spike scenario, inflation expectations become unanchored. Or, the Fed panics and dumps bonds, tightening too quickly, and we have a recession (in other words, both inflation and unemployment expectations become unanchored). Either way, the best way to eliminate these scenarios where the economy becomes unanchored is to follow a suitable rule.

So long as we have people like Plosser and Fisher on the Fed who want to tighten yesterday, the dangers of discretionary policy are pretty low in my mind. But, if a bunch of hawks were to retire, the odds go way up. Especially if we end up with a bunch of doves who are especially bad forecasters.

But as I said, it all boils down to managing inflation expectations during the exit from QE.

Professor,

These is so much good in your analysis I almost hate to point out what is suspect, but let me start there. You wrote:

This is only true when assets are not already leveraged to their highest collateral value. In a situation like that of 2007-8 housing was so over-leveraged that no lower interest rate would have stopped falling housing prices as foreclosures became rampant. Such “stimulus” will only work in an economy that is not over-leveraged and even then only in the short run. Your comment is actually Keynesian illusion.

JDH wrote:

Professor, thank you for this. It is so important to understand and almost no one has grasped the implication, not inflationists, not Keynesians, not monetarists, and not Austrians. It seems that only Supply Side economists understand. As the FED engages in QE their monetary expansion simply goes into reserves. There is no recovery and there is no stimulus. It is all funny money.

That is a curious comment. There has been a fairly robust debate over the extent, and manner, to which QE is effective.

JDH wrote:

Professor, another insight that few seem to grasp. The movement of bank reserves is simply like moving the chairs on the Titanic.

JDH wrote:

Professor, the economy and especially inflation is like turning an Ocean Liner. The only way to either stop it or turn it on a dime is to make it crash into some immobile object. Sadly this has been the SOP of the FED since it was created.

The FED never makes preemptive changes because they fear the political fallout. Then suddenly they are faced with a drastic situation and so slam on the breaks. As Jude Wanniski used to say, “It is not the failure of Keynesian economics that is the problem. It is the actions of the Keynesians when they finally face the fact that their theory fails.” Janet Yellen doesn’t realize it but in her last statement before congress she continue the claims of failure that were routing by Ben Bernanke. She said she had to continue monetary easing until there was a change. In other words, QE in all its forms is not working. “The floggings will continue until morale improves.”

“A number of other studies have looked at the variation over time in the maturity structure of U.S. Treasury debt and have found statistically significant correlations between the maturity structure and relative yields; see for example Kuttner (2006), Gagnon, et. al. (2011), Greenwood and Vayanos (2013), Doh (2010), and Hamilton and Wu (2012) (ungated version here).”

I recently came across the following paper by Daniel Thornton:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/review/2014/q1/thornton.pdf

Thornton estimates the effect of long term (one year or greater) Treasury supply on the term premium and seems to be largely an attempt to disprove prior estimates by Gagnon, Remache, Raskin and Sack (2011):

http://www.ijcb.org/journal/ijcb11q1a1.pdf

Gagnon et al regress the Kim-Wright measure of the term premium on various measures of long-term Treasury supply and some control variables and conclude that Treasury supply is significantly correlated with the term premium. The implication is that QE reduces the term premium since it reduces the supply of long term Treasuries.

Thornton’s main contribution is to show that the addition of trend variables renders these results statistically insignificant.

Both Gagnon et al and Thornton work with the same time period: January 1985 through June 2008. Personally I thought that it was odd that they used these results to form conclusions about the effects of QE. I wondered what the results might look like if we re-estimated them over the time period when there had actually been QE.

I use the same Kim-Wright measure of the term premium as used in both studies. I also use four control variables that both Gagnon et al and Thornton use: 1) the unemployment gap, 2) the year on year core CPI inflation rate, 3) the University of Michigan inflation expectations disagreement, and 4) the 6-month 10-year T-Note realized daily volatility.

I constructed several measures of long-term Treasury supply: 1) outstanding long term Treasuries less Fed holdings, 2) outstanding long term Treasuries less Fed holdings and less foreign official holdings, 3) outstanding long term Treasuries less Fed holdings of long term Treasuries and long term Agencies (one year or longer) and less foreign offical holdings of Treasuries, and 4) outstanding long term Treasuries less Fed and foreign official holdings of long term Treasuries and Agencies.

Consistent with Gagnon et al all supply measures were as a percent of GDP (I interpolated monthly GDP). The only thing I did different from Gagnon et al is that I did not subtract foreign official holdings of corporate bonds, which seemed minor, as well as irrelevant.

I included a trend variable like Thornton in alternate specifications. Consequently I estimated a total of eight specifications of the equation.

The period I looked at was December 2008 to August 2013.

In all of my estimates inflation disagreement and realized volatility failed to be statistically significant, in contrast to Gagnon et al and Thornton ‘s results. Core CPI was highly significant (at the 1% level) but was of the opposite sign as Gagnon et al and Thornton. Thus higher core inflation correlated with a lower term premium. The unemployment gap was not statistically significant in measures of Treasury supply that subtracted Fed or foreign official holdings of Agencies.

But the most interesting result was effect of the measures of supply themselves. All but one were statistically significant at the 1% level (one of the specifications including a trend variable was at the 5% level). But all were of the opposite sign as Gagnon et al. That is, a higher Treasury supply was correlated with a lower term premium.

The only specification in which the trend variable was statistically significant (at the 1% level) was in the measure of Treasury supply that only subtracted Fed holdings of long term Treasuries. Furthermore, the sign was positive, which was the opposite of Thornton’s results.

The fact that Thornton’s trend variable turned out not to be robust to choice of time period didn’t surprise me at all. But the fact that the effect of Treasury supply on term premium is the complete opposite of Gagnon et al was a huge surprise.

Based on Granger causality tests I have previously conducted, QE raises 10-year T-Note yields. (There is also published research showing QE significantly raises bond yields, such as Honda et al 2007.) Obviously the term premium is not the same as the actual yield, but this did suggest to me that Gagnon at al’s results concerning the effect of Treasury supply on the term premium might not be robust under actual QE conditions. But to obtain results that were statistically significantly and of the opposite sign was startling.

Consequently I am now very curious why no similar studies of the effect of QE on term premium seem to have been done during the time there has actually been QE.

P.S. To be clear, I think there is convincing evidence that QE works (e.g. Honda et al, Hayashi and Koeda) , I’m just extremely skeptical that it works through the term premium.

“For example, if assets denominated in foreign currency look more attractive than low-yielding deposits with the Fed, the dollar would have to decline sufficiently until one dollar would buy so little in the way of foreign assets that it no longer is attractive to try to do so.”

It seems like something like that has happened already, much to the consternation of other countries, who have seen undesired appreciation of their currencies. Even with no change in rates, it seems to me that QE can exacerbate the effect, as those who were holding the longer-term debt bought by the fed shift to foreign securities as a substitute. Towards the end of the yen carry trade, Ms. Watanabe got in the act, as the combination of yen depreciation and attractive yields abroad brought in retail participants. So far, I have seen no indication of a like ‘bubble’ mentality in the dollar carry trade, but the trade is surely being conducted. I am waiting for the roll-back, when stock adjustments are reached, the dollar starts to appreciate, and the gains from the carry trade start to fall.

I am so glad that we have a control on inflation and that the reported inflation number does not understate inflation.

Beef prices hit all-time high in U.S.

ricardo, perhaps this has less to do with inflation and more to do with supply and demand? perhaps you do not understand the difference.

Yellen’s Missing Jobs

Excerpt: