Last week the U.S. Federal Reserve closed a chapter on the experiment with quantitative easing, just as the Bank of Japan opened a new one. Seems like a good time to comment on some of what we’ve learned so far.

The conventional way that monetary policy was used to provide more stimulus to a weak economy was to lower the short-term interest rate. The Federal Reserve brought the fed funds rate essentially to zero at the end of 2008, but the economy continued to worsen. So the Fed tried to see what it could accomplish by buying huge quantities of longer-term securities. One theory was that by taking enough of the supply of these assets out of the hands of private investors, the price might be driven up and the long-term interest rate would come down, providing some stimulus to investment and borrowing.

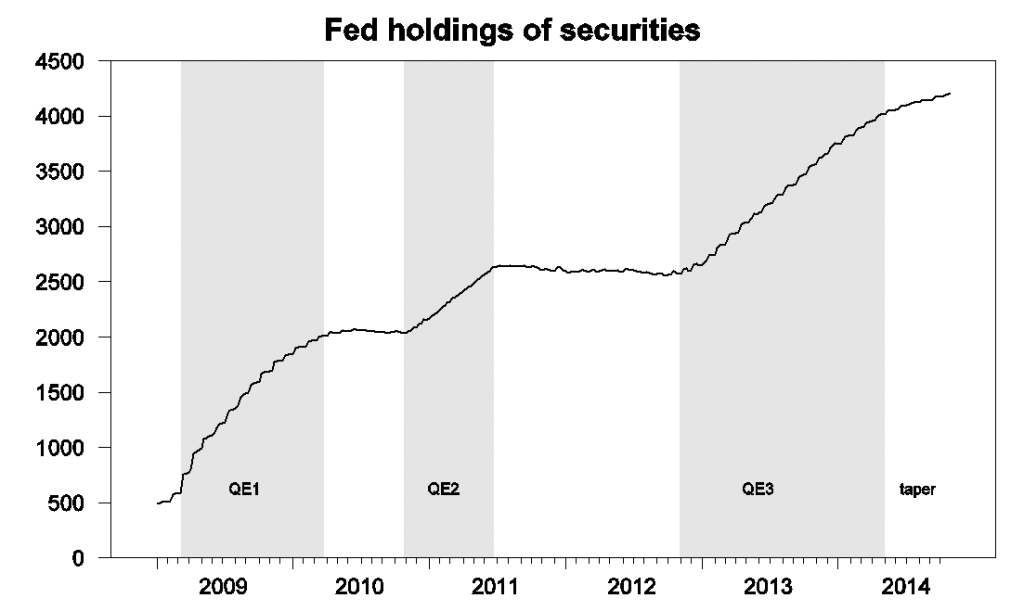

The Federal Reserve’s large-scale purchases of long-term securities came in three distinct phases, popularly described as QE1, 2, and 3. During QE1, the Fed increased its holdings of Treasury, agency, and mortgage-backed securities from $584 B on March 11, 2009 to $2,012 B by March 24, 2010. Those holdings still stood at $2,033 B on October 27 of that year, but rose under QE2 to $2,626 by June 22 of 2011. After another pause, the Fed resumed large-scale purchases with QE3, under which its net holdings increased on average by $20B a week between November 2012 and December 2013. At that point the Fed announced its dreaded “taper”, initially a barely perceptible decrease in the rate at which the Fed would continue to add to its holdings, but which finally brought net new purchases down to zero with the Fed’s announcement last week. I’ve associated the start of the taper in the graph below with April 30 of this year, the date by which net purchases had fallen to about half the pace of 2013.

Figure 1. Federal Reserve holdings of Treasury, agency, and mortgage-backed securities, weekly, Jan 7, 2009 to Oct 29, 2014. Excludes inflation compensation and unamortized premiums or discounts. Data source: H41.

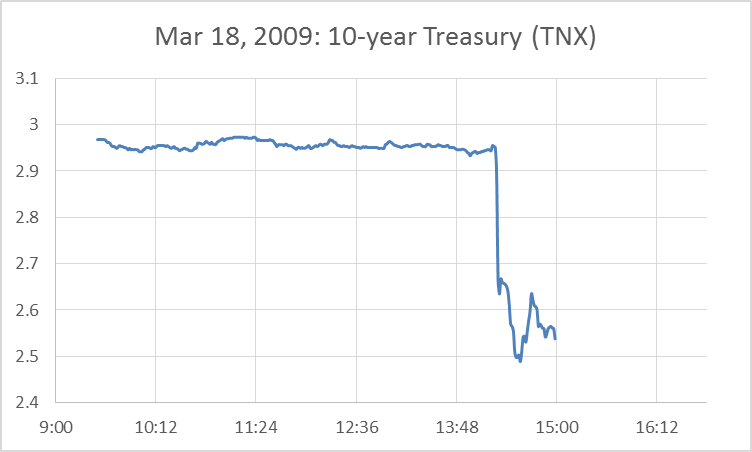

A number of research papers have attempted to measure the effects of these policies. The graph below illustrates the kind of evidence on which many of these studies relied. On March 18, 2009 the Fed announced that it would purchase up to $1,150 additional securities. Within minutes of the announcement, the yield on 10-year bonds had fallen by 40 basis points.

Figure 2. Yield on 10-year U.S. Treasury securities on March 18, 2009, as measured by the price of the TNX contract.

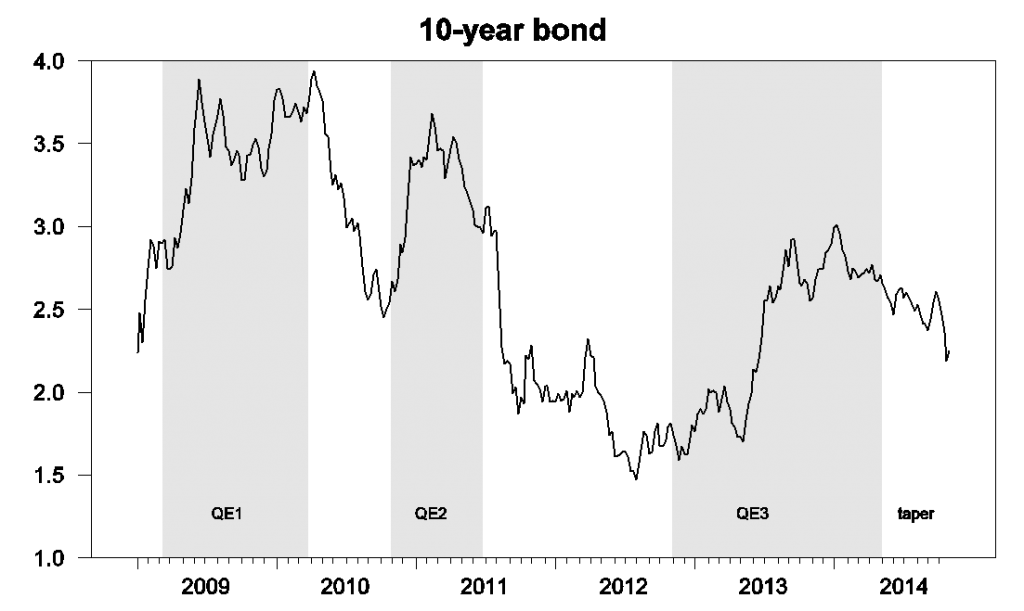

But over the next few days, the yield started climbing back up. By the end of April, the 10-year yield was higher than it had been before the Fed’s announcement. Columbia Professor Michael Woodford invited us to take a longer-term perspective on the effects of these policies. I’ve updated the idea behind one of his graphs using the above designation of the three policy regimes. On balance the 10-year yield rose during QE1, and only fell when the Fed stopped trying to do anything. Yields rose again during QE2, and again fell when the Fed stopped adding to its purchases. Yields also rose during QE3, only to decline as the dreaded taper unfolded.

Figure 3. Yield on 10-year government bonds, weekly, Jan 2, 2009 to Oct 24, 2014, from FRED.

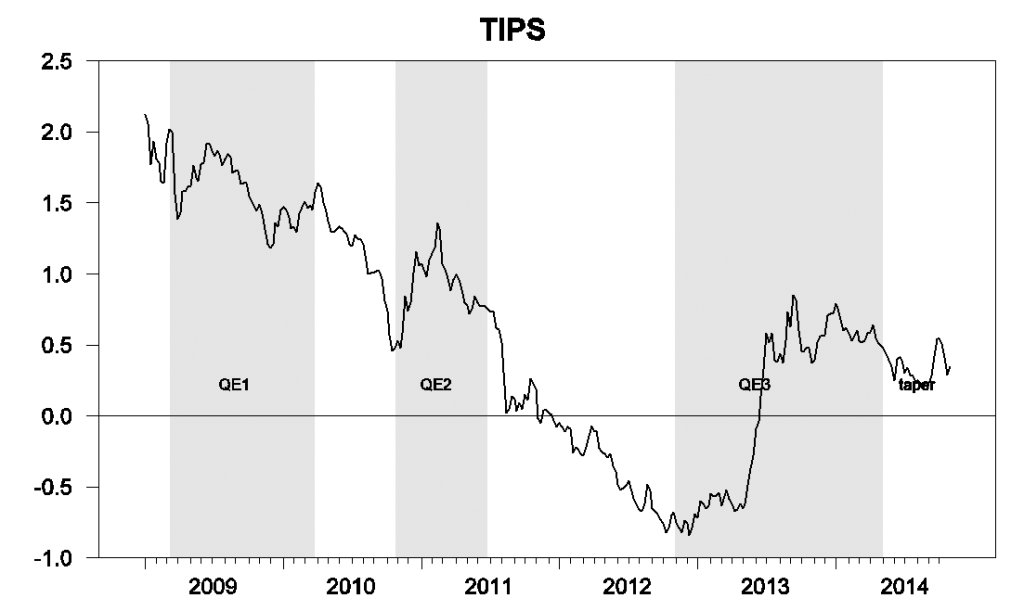

Possibly the large-scale asset purchases had effects through other mechanisms. One theory is that the Fed’s asset purchases could have raised inflation expectations so that, even if the nominal interest rate rose, the real interest rate could still have been driven down. A quick measure of real rates is provided by the yield on 10-year Treasury Inflation Protected Securities. The tendency to rise during QE2 and 3 and to fall during the periods when the Fed did nothing is if anything even more dramatic in real yields than it was for nominal.

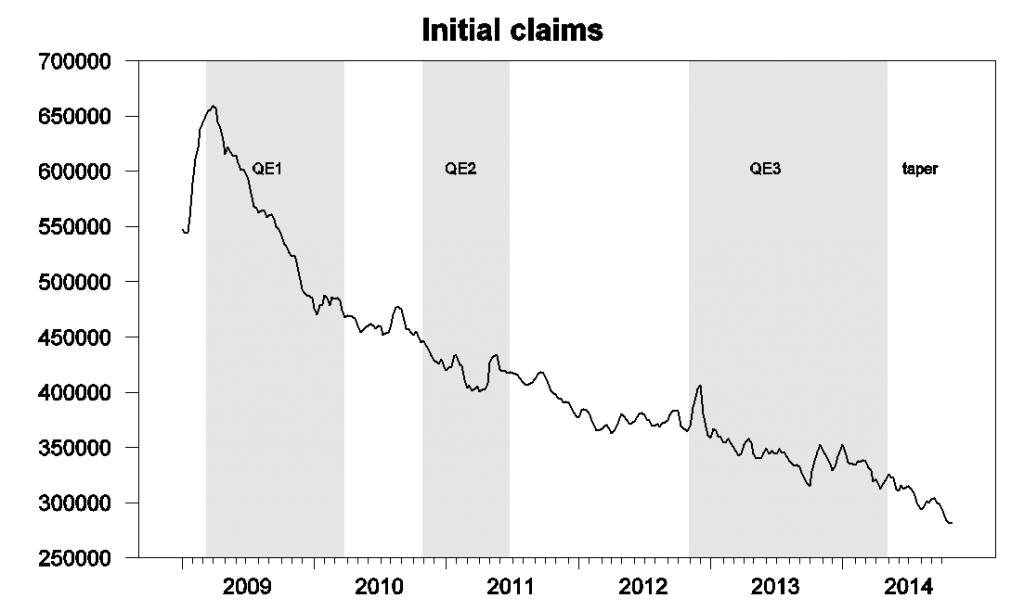

Perhaps the measures affected the economy through other channels, a theory that one analyst described to me as “immaculate conception.” Here’s a graph of initial claims for unemployment insurance. New claims dropped dramatically as the recession ended, and that coincided with the period when QE1 was still in effect. But if you can see an impact of QE beyond that, your eyes are sharper than mine.

Personally I am persuaded that the Fed’s actions did have some effect. It’s impossible to look at Figure 2 above and claim otherwise, and there are a number of studies that use methods other than the event-study approach in Figure 2 that support the conclusion that these policies can have some effects. But it seems to me that the fair conclusion to draw from Figure 3 is that, whatever these effects may have been, other developments beyond the control of the Federal Reserve have likely been more important in determining what happened to long-term bond yields over the last 5 years.

Fortunately from the point of view of economic research, the Bank of Japan has decided to provide us with some more data. The BoJ announced on Friday massive new asset-purchase plans, intending not only to buy government debt at twice the rate it is being issued by the Japanese treasury, but also to buy stocks and real estate funds directly. Japanese stocks rallied immediately in response to the news.

Source: Wall Street Journal.

But what I’ll be interested in seeing is how long the effect turns out to last.

I was impressed by the choice – or coincidence – that BoJ announced after the US Q3 GDP report came out strong and the Fed said “gee, things are looking pretty good”. If BoJ wants to push up inflation, push down the yen, it helps if the US both the $ and the economy are strengthening. Gives them room to move.

The feeble effects of quantitative easing illustrate that the risks of the zero lower bound are as important if not more important than the risks of inflation. This means that an inflation target of 2% provides an insufficient buffer for deflationary shocks, especially when faced with an uncooperative Congress.

The fact that the Federal Reserve Bank considers inflation to be the more important risk in the face of all evidence to the contrary indicates that they only take half of their mandate seriously — the protection of the creditor class.

Why have a Federal Bank that is insulated from the interests of citizens, allowing them total freedom to protect their banker friends?

James: take a standard ISLM model, then assume that dI/dY > 1 (there is a strong “accelerator” type effect on investment demand, because few firms want to invest if they expect demand will be weak). The IS curve now slopes upwards. A rightward shift in the LM curve, due to QE, will increase real interest rates, as well as nominal interest rates.

Nick, you’re arguing that QE was counter-productive, ie, actually harmful?

Steven: no. Just the opposite. But interest rates are a very poor measure of the effectiveness of monetary policy. A loosening of monetary policy, that raises aggregate demand, can cause both real and nominal interest rates to rise.

So how would you then know whether QE2, QE3 and Operation Twist had been a success? What’s the metric? The Fed itself used a lowering of interest rates as the desired outcome.

I support Nick Rowe’s comment here. The IS curve is based on the monetary policy curve, where as inflation rises, central banks will increase the real interest rate. So there is a positive relationship between real interest rates and inflation (up-sloping curve). However, central banks cannot control real rates with the current ZLB. So we have a situation where falling inflation will raise real interest rates. The monetary policy curve slopes down, not up. The IS curve will consequently slope up as Nick Rowe says.

So when you transfer higher real rates and lower inflation to the aggregate demand curve, you see that as inflation falls, so does output. The aggregate demand curve slopes up. In effect, QE has not helped aggregate demand.

Thus it is crucial that the Fed rate lift off of the ZLB…. something which should have happened earlier in this business cycle when there was economic momentum. The ZLB and QE is hindering output.

QE has had a positive effect on growth, ceteris paribus.

However, in part, because of excess reserves, QE has had a smaller effect.

Chart:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/EXCSRESNS

It’s easy to confuse the leads and lags of monetary policy with causes.

For example, the Fed will tighten the money supply before growth accelerates.

However, some people will assume, because the Fed tightened the money supply, growth accelerated.

Accommodative monetary policy, including QE, raises inflation expectations, to facilitate nominal growth, and therefore, real growth.

The real fed funds rate is a measure of monetary ease or tightness. If the real rate is below the natural rate, it is expansionary and, with a lag, inflation will accelerate unendingly. If the real rate is above the natural rate, it is restrictive and inflation will decelerate. Prior to the crisis, the relationship between the real rate and inflation was manifestly nonlinear. In today’s era of artificially suppressed rates, one is hard pressed to find any kind of relationship between the real rate and inflation. To a large extent, this has to do with the monetary transmission mechanism still being badly broken. At the endpoint of the mechanism, the velocity of money is still falling. Why might this be? My instinct is that private sector debt (the debt ratio) is still far above optimal, and that households were made keenly aware of this during the crisis and are acting accordingly. The consequences of twenty-some years of profligate borrowing will not be remedied overnight.

A very good point. And it does not need dI/dY>1 to go through, what is needed is only dC/dY+dI/dY>1 – which is quite plausible!

The saying goes something like the bond market has predicted eight of the last three recessions.

And, it seems, the bond market sends signals to the Fed, including through the yield curve.

Generally, accommodative monetary policy boosted both the bond and stock markets.

However, it seems, excessive banking regulations raised lending standards too high for small business and home loans:

“Small businesses employ roughly half of the private sector labor force and provide more than 40 percent of the private sector’s contribution to gross domestic product. If small businesses have been unable to access the credit they need, they may be underperforming, slowing economic growth and employment.

A combination of reduced creditworthiness, the declining value of homes (a major source of small business loan collateral), and tightened lending standards has reduced the number of small companies able to tap credit markets.”

http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/commentary/2013/2013-10.cfm

PeakTrader,

you are saying two different things:

On one hand you said: “it seems, excessive banking regulations raised lending standards too high…” and on the other hand you said: “….tightened lending standards has reduced the number of small companies able to tap credit markets.”

I think it is important to point out that ” tightened lending standards” are not necessarily rooted in “excessive banking regulations”.

In fact I think it is unlikely that lending standard were significantly caused by banking regulations, and much more likely that they were rooted inside the banks themselves.

Other than that, I agree totally with your post.

Bellanson, so, you believe banking regulations after the financial crisis, including Dodd-Frank and Basel III, with greater activity and enforcement by the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission, along with the Justice Department, didn’t have a significant effect on bank lending?

What about “too-big-to-fail?”

peak, i think banks realizing they are now responsible for the losses resulting from their loans, if they occur, has been the major tightening factor. you could say this is now in existence because of regulations, but the reality is the banks are tightening because they do not want to lose money. that said, of course regulations are having an effect, but mostly in forcing banks to behave the way they did before the crazy years of 03-07.

Banks shouldn’t lend money to people with no money down and no income, e.g. when Congress created the moral hazard in the housing market that resulted in the boom/bust cycle.

Also, it doesn’t help the economy when banks are hunkered-down by excessive regulations, e.g. after the housing boom.

If Congress gradually tightened lending standards when the Fed began the tightening cycle in 2004, the financial crisis may have been averted.

Bush Administration Tried to Reform Freddie and Fannie Five Years Ago

February 19, 2009

“Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac “accelerated their imprudent behavior after we attempted to regulate them. They bought almost as much mortgage debt from 2005 through 2008” as they bought in their first 30 years of their existence.

In 2003, when we sent our first members of the Cabinet up to talk about this on Capitol Hill, Barney Frank had a hearing in which they basically beat up everybody we sent up there in pretty vociferous language.

In fact, we moved aggressively in 2004 to regulate Fannie and Freddie, actually got a bill through the Senate Banking and Finance Committee only to have it filibustered by [Sen.] Chris Dodd.”

peak, fannie and freddie worked on mortgages which were fraudulently documented by home buyers and especially the mortgage brokers and bankers. now they could have been more diligent on the paperwork themselves, true. but you need to clearly understand the illegal activity and fraud occurred in the steps prior to fannie and freddie involvement-and this involved the private enterprises throughout the mortgage processes. subprime, to which you refer, was a frankenstein of the private marketplace.

Professor,

You must also look at the “creative” programs that Bernanke instituted before QE1. As these programs were phased out they sterilized the monetary affects of the stimulus.

Then also you must look at the massive increase in bank reserves. This increase was not because the banks were refusing to loan money – that is absurd on its face since banks make money by lending – they increased because the economy could not support more currency and so excess money was parked in reserves at the FED.

But I do like your second paragraph:

“The conventional way that monetary policy was used to provide more stimulus to a weak economy was to lower the short-term interest rate. The Federal Reserve brought the fed funds rate essentially to zero at the end of 2008, but the economy continued to worsen. So the Fed tried to see what it could accomplish by buying huge quantities of longer-term securities. One theory was that by taking enough of the supply of these assets out of the hands of private investors, the price might be driven up and the long-term interest rate would come down, providing some stimulus to investment and borrowing.”

The monetarist theories of the FED do not work. The Great Recession is not the first evidence but is the most current and one of the most dramatic. Until economists actually return to a study of capital and its relation to prosperity, we will be playing numbers games with no meaning in the real economy.

Capital is and always has been the key to economic health and prosperity. This is why the protection of private property rights is so important. With our current government not only failing to enforce private property rights but actually working to destroy these rights, any economic recovery will remain a struggle.

Professor,

Would you also post a graph of the components of the FED balance sheet?

This is kind of a damning indictment, Jim.

As I’ve been reading some of the bank’s own analysis of QE (specifically QE2 and forward), it’s hard to avoid the impression that a number of the bank’s staff are of the opinion that that the latter QE’s were little more than an ill-advised publicity stunt, with minimal effect on GDP growth at the cost of potentially large and poorly understood risks to both the Fed’s balance sheet and the economy more broadly.

QE nothing other than can kicking. Surreptitious and malign distortion of the entire market price mechanism. Decimation of savers’ and retirees’ incomes. Utterly pathetic and bordering on criminal. Next crisis will be worse because of debt and asset price bubbles enabled by QE. Mainline injection of funds created out of thin air to enable government debt bubble, stock market bubble, home price bubble. Effect on real economy so miniscule economists struggle to identify even the transmission channels! Again, pathetic. Malinvestment from last crisis not fully cleared away, yet capital goods sector piled afresh with new malinvestment created during this spate of artificiality. Two point three percent real growth, yet Federal Reserve sweating bullets that the first rate hike will pull the pins from under this house of cards and bring it tumbling down. This is not the full, but it is the core, of the story. The full extent of the unintended consequences of ZIRP and two-QEs-too-many are yet to reveal themselves, with nary a single paper on these consequences from the mainstream or the timid, muzzled economists at the Fed who would risk losing their job if they aired these like true scientists ought.

The announcement of Japan’s new QE round was not the only news affecting the markets. At the same time the Japanese CB announced it would be buying stocks and bonds, the $1.2 trillion Japanese national pension fund announced it would be selling bonds and buying stocks (the new bond buying/selling seem to be roughly offsetting):

“Under the new allocation guidelines, Japanese stocks and foreign stocks will each take up 25% of the fund’s holdings, up from 12% each previously. The fund intends to put 35% of its money in domestic bonds, down from 60%, while the ratio for overseas bonds will rise to 15% from 11%.”

http://online.wsj.com/articles/japan-mega-pension-to-shift-to-stocks-1414720683

And, this followed an earlier coordinated effort in June 2013:

“The changes mark the first rebalancing by the fund since 2005 and will raise their allocation of domestic stocks to 12% from 11%. Foreign stockholdings will also increase to 12% from 9%, while foreign bonds will rise to 11% from 8%. Domestic bonds, composed primarily of Japanese sovereign debt, will be reduced to 60% from 67%. The remaining 5% is in cash or short-term assets.”

http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424127887323844804578530541651768054

QE is not the entire story here.

While the monetary base has increased by a huge amount, it seems to me the Fed does not hold these securities that they sucked out of the economy in any real sense. Hence the notion of helicopter money. The securities have disappeared, as we all learned in money and banking 101, and are replaced by dollars. This is because all interest paid by the treasury to the Fed is returned to the treasury. The same is true of face value if held to maturity. Thus, the whole notion of a balance sheet is something of a misnomer unless these treasury liabilities are included, in which case the liabilities net out the assests. Now, the Fed (apparently?) has a substantial quantity of gold, much more (like 25X) than on its balance sheet since that is book value rather than market value. That is something they really have.

‘Perhaps the measures affected the economy through other channels [than interest rates]…’

I think you’re on to something there.

‘…a theory that one analyst described to me as “immaculate conception.” ‘

He hasn’t heard of David Hume (or Milton Friedman, or Scott Sumner)?

“Evaluation of QE?” Oh, please. Everybody knows the QE has been great for the Stock Market, and the Central Bankers, the criminal shyster politicians and banksters, the moneyed elites, and the corporate oligarchs. Not so much for the average person. But, hey. We are all use to living very open deaths by now. QE should be called Open Death (OD), and numbered, too. This is OD 3.

I think the way to understand QE is to first grasp that paper currency, commercial bank deposits, Treasurys and agencies are all fairly similar things. Most are publicly issued, and all are de facto publicly backed. (Even if not all commercial bank deposits are FDIC insured, in practice the FDIC always keeps them whole; the confusing implicit public backing of agencies was made explicit in 2008.)

Such financial assets, thus, form a group. Let’s call publicly backed assets.

The direct effect of QE is to change the composition of publicly backed assets. For example, $300bn of Fed purchases of Treasurys reduces the supply of Treasurys by $300bn and increases the supply of cash (paper currency and/or commercial bank deposits) by $300bn.

QE however does not directly change the scale of the total supply of publicly backed assets. The size of that total supply is determined by Treasury, the GSEs and commercial banks – through issuance of Treausurys and agencies, and commercial bank lending and asset purchases.

The indirect effects of QE are much more difficult, if not impossible, to know. For some, there is a widely accepted theory widely believed to be confirmed by events: Fed purchases of long-term assets should flatten the term curve; flattening of the term curve should increase the present value of assets; increases in money supply should drive down the value of cash as an asset and thus drive up the cash prices of other assets. But even these, most sensible theories of QE’s indirect effects can be and are disputed.

Many people wrongly look at the size of M0, reserves or excess reserves to gauge the scale of QE’s affects. That makes no sense. The amount of reserves only matters up to the point at which there is enough that overnight interbank rates are near zero. After that point, additional reserves make no difference. By the time QE was initiated in March 2009, commercial banks already had more than $600b of reserves, and interbank rates had been near zero for several months. Note that I don’t even include reserves in my total supply of publicly backed assets. That’s because reserves aren’t held by the real economy. The real economy holds commercial bank deposits, and reserves are merely one of (and the safest of) the assets that commercial banks hold to back up those deposits.

What does matter however are the additional commercial bank deposits created by QE. QE creates commercial bank deposits whenever the net sellers of Treasurys or mortgage debt during the Fed’s purchases are anyone other than commercial banks. Many people don’t realize that QE creates commercial bank deposits, as much of the writing about QE portrays it as purchases of assets from banks. Actually the supply of assets comes mainly from issuers – the main net sellers of Treasurys and agencies are Treasury and the GSEs. (Besides, the Fed buys directly from broker-dealers, not banks, but it’s the net seller, not the direct seller, that matters.) Commercial banks more often bought alongside the Fed than sold into its bids.

Tracking QE’s affect on M2 is a little more difficult than tracking its affect on M0 or reserves, because other factors are also at play, especially bank lending and asset purchases. I won’t go into any detail, but the effect of QE on M2 is readily apparent from the fact that M2 is up by $3.7t since just before Lehman while commercial bank credit is up by only $1.3t.

QE can’t be understood in isolation. It’s a component of overall fiscal and monetary policy. The Fed is only one of several major public actors in the fiscal and monetary space. For example, Jim describes Fed purchases as “taking … supply of these assets out of the hands of private investors.” But actually the Fed was usually reducing the pace at which supply of was being put into the hands of private investors, because the supply from the issuer was greater than the Fed’s purchases.

RE: Japan, I think what’s most interesting is the starkly different effects of US and Japanese QE on FX rates. US QE’s affect on FX rates is disputed and at most modest, whereas Japanese QE’s affect on FX rates has been large and obvious. Clearly, increasing yen supply has a much bigger effect on how the the yen is valued relative to foreign assets than increasing dollar supply has on how the dollar is valued relative to foreign assets. The reason I think must stem from the dollar’s greater international role, but I can’t explain exactly why nor have I seen anyone else successfully explain it.

I stated before, without the Fed, there wouldn’t have been any growth at all over the past few years.

Lower interest rates and higher asset prices induce people to spend and borrow, and reduce saving, a lower cost of capital spurs production, refinancing at lower rates increases discretionary income, lower mortgage rates makes buying a home more affordable, 401(k)s and IRAs increase in value, etc.

There are massive multiplier effects throughout the economy.

Bob Brinker agrees with me:

December, 2012

“It’s only because the Federal Reserve has been active that we have any growth at all in the economy….The Federal Reserve is the only operation in Washington doing its job.

The only person that would criticize Ben Bernanke would be a person who is so clueless about monetary policy and (the) role of the Federal Reserve as to have nothing better than the lowest possible education on the subject of economics….Anybody going after Ben Bernanke is a certified, documented fool….”

And I did not criticize Ben Bernanke.

Professor Hamilton, my comments weren’t directed at you.

They were directed at a few other people.

I think, they know who they are 🙂

Yeah, I guess that includes me. So basically your theory is that the productive capacity of the United States would have withered and collapsed over the past six years had it not been for QE, due to an overly high savings rate. And I’m a fool for not believing it. Gotcha.

Tom, low rates helped fuel the boom in oil production.

JDH: “I did not criticize Ben Bernanke.”

Well, I certainly did.

Congratulating Ben Bernake for his performance is like congratulating an arsonist for being the first on the scene with a fire extinquisher. All through 2005, 2006 and 2007 Bernanke testified over and over that there was no housing bubble and that subprime mortgage securities, NINJA loans and all, posed no threat to financial stability. He did nothing to prevent the impending crash and even recommending against attempting to.

When disaster struck he was very aggressive about protecting the banks but much too timid in concerns about unemployment and the average working American. Normally there is a tug of war between inflation and employment. It takes a supremely incompetent central bank to undershoot both targets simultaneously.

A 2% absolute ceiling for inflation in the face of the worst recession since the Great Depression is down right criminal. When weighing the risks of inflation vs unemployment, he always deferred to the hawks fears of inflation. He should bear the burden of millions of ruined lives for all posterity, reviled along with Andrew Mellon for his depraved indifference to human suffering.

The Bernanke Fed was very busy putting out the fires in 2008 caused by Congress.

And, then it had to deal with the subsequent and ongoing train wreck after 2008 created by the Obama Administration and Congress.

The Fed did everything it could.

You can praise the Fed later.

Someone might be able to argue that the fed enabled Obama and Congress.

The Fed may have caused the recession, initially, tightening the money supply from 2004-06 and maintaining a restrictive stance too long.

However, the U.S. was on a path to a mild recession thanks to the Bush tax cut in early 2008, which gave the Fed time catching-up easing the money supply, until Lehman failed in September 2008.

The financial crisis was the result of a giant social program in housing Congress believed it didn’t have to pay for.

And, we could’ve had a much stronger recovery from the severe downturn after September 2008.

“The financial crisis was the result of a giant social program in housing Congress believed it didn’t have to pay for.”

no, it was an investment scheme that financial engineers did not believe they had to pay for.

Joseph,

I would like to get links / evidence for your

“All through 2005, 2006 and 2007 Bernanke testified over and over that there was no housing bubble and that subprime mortgage securities, NINJA loans and all, posed no threat to financial stability. He did nothing to prevent the impending crash and even recommending against attempting to.”

Not because I dont believe it, but I want to have references for the discussion in Europe

“The Federal Reserve brought the fed funds rate essentially to zero at the end of 2008,”

A close look reveals the market drove rates down in 2008, the Fed just followed along.

Jim, you write, “One theory is that by taking enough of the supply of these assets out of the hands of private investors, the price might be driven up and the long-term interest rate would come down, providing some stimulus to investment and borrowing.”

This might be a good description of the policy goals if we were just hitting the zero lower bound after a normal recession, but I don’t think it accurately reflects the problems the Fed was trying to address with QE. As you know, QE1 was undertaken at a time of extreme market illiquidity and in the wake of rapidly rising Federal debt. QE2 took place when the private sector was deleveraging and Europe was in fiscal crisis, and QE3 was taken out as insurance against the “fiscal cliff” and US fiscal austerity. Each of these episodes distorted the supply and demand for US Treasuries in unpredictable ways, making it hard to determine cause and effect on interest rates. QE might not have reduced rates in absolute terms, but may have done so in comparison with the alternative. One way I’ve tried to look at the counterfactual is by comparing Federal debt/GDP to the same ratio net of QE purchases:

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=PMn

I find it interesting that, because the Fed absorbed so much of the new supply, Federal debt/GDP was capped at R&R’s 90% “threshold.”

Maybe I’m looking at this too simplistically, but it seems to me the main goal of QE wasn’t to cut rates as a way to indirectly stimulate investment, but to more directly help deleverage the economy – first for the housing and financial markets, then at the Federal government level.

Joseph,

You criticize Bernanke for “A 2% absolute ceiling for inflation” while he was doing everything he could to get up to 2%. You criticism is a little hollow. The FED doesn’t know how to get inflation up to 2% so a 2% ceiling is meaningless.

He was doing everything he could to get up to 2%. The FED doesn’t know how to get inflation up to 2% so a 2% ceiling is meaningless.

Ah, but we know that he wasn’t doing everything he could. There was an important paper in 1999 called “Japanese Monetary Policy: A Self-induced Paralysis” written by none other than Ben Bernanke. In the paper Bernanke chided the Bank of Japan for its timidity and outlined the the prescription for exiting the liquidity trap.

1. First he prescribed real and convincing zero interest rates with long term inflation of 3% to 4% and more importantly, genuine promises to keep it up for many years past a return to economic normalcy. Instead we got a timid 2% ceiling and quarterly speculation about raising rates as soon as possible. If you don’t sincerely promise long term inflation, no one will believe you. But even if they don’t believe you, you can force inflation with the following steps.

2. Devaluation of the currency by selling dollars on the exchange market, as much as necessary, buying up under-valued currencies. Due to an over-valued currency, particularly with respect to China, the U.S. was running trade deficits as high as 6% of GDP. The over-valued currency functions as a tariff on exports, making U.S. products less competitive and keeping U.S. unemployment high. Currency devaluation would help progress toward the domestic inflation target and reduce unemployment.

3. Helicopter drops of money from the Fed directly to households. You keep pumping money directly to households, not sterile reserve bank accounts, until you get the desired inflation.

4. And lastly, quantitative easing. Quantitative easing was the least important of these methods. Bernanke said that QE shouldn’t even be necessary if the other methods were used.

So we know that Bernanke did not lack the knowledge or tools. He expressed them very clearly. He was the most powerful person in the world, uniquely positioned to do what he had prescribed.

Bernanke said that what was needed was Rooseveltian resolve — the courage to do what needs to be done. Yet he was, ironically, struck by a self-induced paralysis. What he lacked was courage and for that he can’t be forgiven.

Japanese Monetary Policy: A Self-induced Paralysis

This is what is so maddeningly frustrating about Bernanke. He was uniquely suited for the job. He had spent his career studying the mistakes and lessons of the Great Depression. A decade earlier he had carefully written out a step-by-step plan for how to tackle a liquidity trap. It was as if his entire life had been training for this one important moment to be a hero.

And what happened? He failed to execute his plan. Did he get cold feet? Was he a coward? Was he bought off? Was he beaten into submission by the bankers? Was he assimilated by the Borg? It is still a baffling mystery.

Personally I am persuaded that the Fed’s actions didn’t have any effect at all. Not even can kicking. But the wording “immaculate conception” from one of your economy friends. see above in the 5th chapter, is really funny.

Anyway James, enjoy your coffee cup reading.

Charlatans.

I believe prolonged (past the early recovery stage) ZIRP and QE are hindering growth. The entire price mechanism has been thrown out of whack by the suppression of rates. Economic efficiency must ipso facto be blunted. This lowers the trajectory of potential growth going forward.

There is something bigger going on beyond the Fed’s ken. Mistakes of the past culminated in the Great Recession, which washed over the fertile fields of the economy with great devastation. The core causality – as is the case with rare exception – was years of too much spending on credit. Credit leaves behind its twin – debt. One of the hallmarks of this different and challenging post-crisis era is the record high burden of debt (debt-to-GDP or debt-to-income). It is the pernicious legacy of the past. ZIRP and QE aim to accelerate the growth of credit so that incremental spending enabled by ordinary income is augmented by additional purchases made on credit. To be effective in achieving this aim, credit must perforce grow faster than income. But given the debt legacy, debt ratios are already beyond optimal. How then can it be correct to stimulate with more credit and debt?

The Fed is reticent to unhinge ZIRP and raise rates. This would, it is thought, increase the real rate and push quiescent inflation toward disinflation and eventually deflation. The downside is the presumed impact on aggregate demand of a lessening of credit growth. Everything is viewed through the lens of aggregate demand. AD is the sacred cow of mainstream economics.

But interest rates are a two-edged sword. There are many benefits as well to raising rates (e.g. greater interest income, greater net interest margin for banks, inducement to save, throttling down the rate of malinvestment in this era of artificiality, less demand leakage to imports, nipping future financial crises in the bud, and so on).

Stepping back for some perspective, plenty of time has gone by for this economic morass to no longer be thought of as cyclical. The morass is now nearly all structural. This point is critical. Structural policy changes are mostly exogenous to the Fed. In this light it is fair to ask: How sensible and sustainable can the necessary structural changes be when undertaken in the mother of all artificial monetary environments? Fed policy is both pushing and pulling against structural change, not aligning smoothly with it. This is the deeper reason to end ZIRP and begin to normalize rates.