Today we are fortunate to have a guest contribution by Robert J. Schwendinger, former Executive Director of the Maritime Humanities Center of the San Francisco Bay Region, and author of the newly republished volume Ocean of Bitter Dreams: The Chinese Migration to the United States, 1850-1915 (Long River Press).

In my work, Ocean of Bitter Dreams, I document the workings of imperialist economics for a critical era in trans-Pacific relations. Those nationals in China — the British, French, Spanish, Dutch, Prussians, and many Americans — preyed on vulnerable Chinese during the formative years, and reaped unimaginable fortunes for that time.

Opium and “Free” Trade

My book traces the actions of Americans who participated in the Opium Wars, the “coolie” trade — essentially a parallel slave trade — and the treatment of immigrating Chinese to the United States. Their attitudes are bound irrevocably to the exclusion of Chinese well into the 20th Century.

Opium was a prime merchandise of the age. By the time the Emperor directed Prince Kung to move against the illegal importation along the coast, the complex network was virtually impregnable. The Imperial Navy was a ghost of its former self, suffering from measures taken in the Fifteenth Century to reduce the high costs of a grand navy. Existing vessels were few, slow, and ineffective.

Interests as far as half a globe away depended on the illicit opium. Bengal received over half its revenues from the cultivation and sales, as traders, shippers, captains, bankers in England, the United States, and Portugal, reaped ever increasing profits from its distribution. American’s share of the drug was approximately twenty-percent, taking the lion’s share from Turkey. Leading American traders such as Samuel Russell and Company and John Jacob Astor were part of an interlocking, mutually supporting network that included among other New Englanders, John P. Cushing, and the Perkins brothers.

Prince Kung, a key statesman in the late Ching dynasty, attempted to put a halt to the traffic in 1839. He appointed Commissioner Lin Tse-Hsu to carry out a firm policy against the opium trade. Lin wrote Queen Victoria, and asked why she was forcing opium on the Chinese even as she forbade her own people to smoke the drug. He asked if there was no end to Britain’s desire for profit. After receiving an unsatisfactory reply, Lin set out to destroy 20,283 chests of opium that were confiscated from foreign factories at Canton, eight floating depots, and coastwise clippers. The 3,564 pounds of “black dirt,” worth about ten million dollars at that time, was pulverized on platforms suspended across huge trenches, then laborers stirred the residue in water, salt, and lime. Boiling from the volatile mixture, the trenches looked like great scalding furnaces; the stench was overwhelming in the intense heat of the Canton Delta. It took two months to collect the valuable contraband and thee weeks to dispose of it. In anticipation of the wholesale destruction, Commissioner Lin prayed to the God of the Sea, appealing to all sea creatures to seek safe harbors until the “poison” dispersed throughout the seas.

Shortly after the destruction of opium, England sent the largest expeditionary force ever witnessed in Chinese waters. The first Opium War led to another in 1856, then in 1860 British and French troops destroyed the magnificent and singular treasure house of China, the incredible Summer Palace outside Peking. Palace grounds included forest, gardens, man-made lakes, bridges, and a compound of two hundred buildings, many roofed with gold. They were filled with the finest silks, jade, gold ornaments, rare art, and irreplaceable libraries. In a highly symbolic act, comparable to the sack of Rome by the barbarians, those armies looted and reduced to ruins what took centuries of Chinese culture to produce.

After approximately eleven years of hostilities, gunboat diplomacy wrested over fifty million dollars in indemnities; ceded the island of Hong Kong to Britain, including the New territories, 376 miles of mainland, islands and bays; and granted extra-territoriality rights to the allied powers.

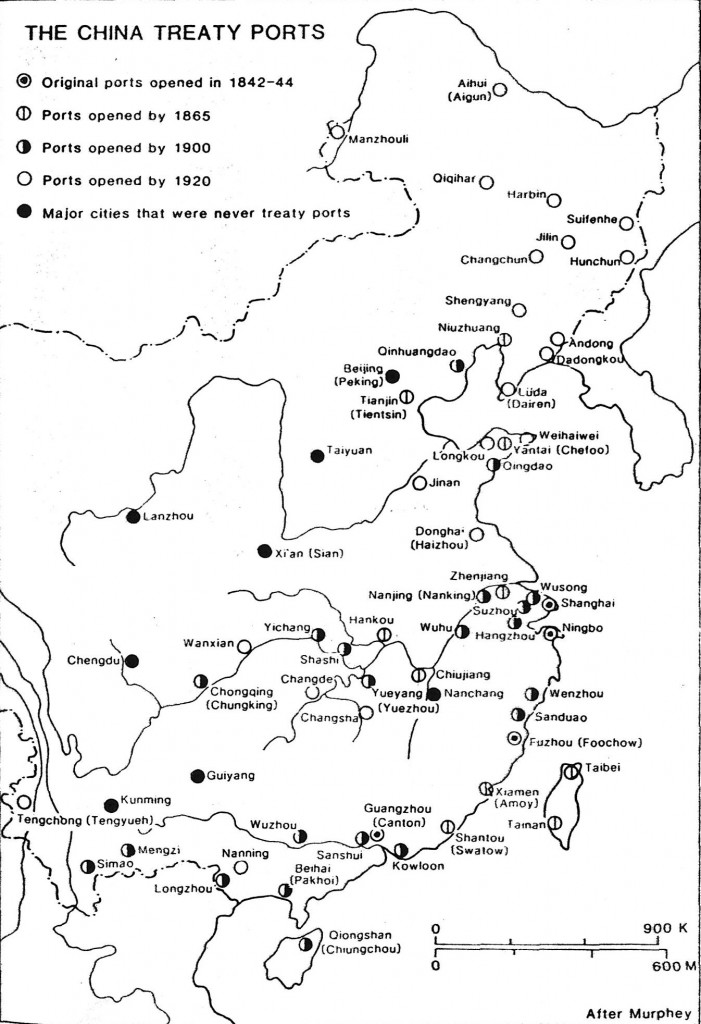

The agreements that grew out of China’s bitter experience have been described as the “unequal treaties.” Eventually all Western shipping was freed from Chinese control in her own waters. The five Treaty Ports that were granted after the first Opium War eventually grew to eighty by the end of hostilities. Missionaries were accorded freedom to proselytize anywhere, and opium was blessed with legal status, becoming the prime merchandise of the age. Imports increased over three hundred percent in ten years.

Figure 1: Five Treaty ports were opened to foreign trade in 1842 as a result of the first Opium War: Canton, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and Shanghai. The number eventually grew to more than eighty. The Liu-chiu Islands, or Lew Chu, is currently the Ryukyu Archipelago.

The “Coolie Trade”

The unequal treaties drove China into a position of astonishing vulnerability. The infamous “Coolie Trade” would not have been possible without the opening of all those treaty ports and the granting of those extraordinary rights.

Hong Kong was an economic and symbolic prize. It depended on the distribution of opium, the increase of Chinese residents, a large percentage of import/exports between China and other countries, the emigration movement, and the manufacturing of chains and other restraints that were used in the “Coolie” trade.

While African slaves were being freed in the United Kingdom and South America, the “Coolie Trade” grew out of the desire to supplement or replace the slaves. The term “Coolie,” became the derogatory designation for cheap, mostly servile labor.

The discovery of gold in California attracted Chinese as immigrants, as were populations in other parts of the world. There grew out of the movement those Chinese who were considered “free” emigrants, who were able to pay for their tickets to the United States, as distinguished from “coolie” immigrants, in the belief that the ability to pay for the voyage was a qualitative difference between the two. Those without the ability to pay and entrusted themselves to contractors or were deceived into shipping out, were sent to the Sandwich Islands, Mauritius, Panama, Peru, Brazil, and the West Indies. They were looked upon as “coolie” and maligned with a host of descriptions, from “voluntary slaves” to a “degraded class of semi-barbarians.”

As attractive were the rewards from opium for British, French, Portuguese, and Americans, especially, the rewards for recruiting unsuspecting Chinese men and boys were just as high. Shippers and captains depended on unscrupulous brokers to entice Chinese to the ports, as they were either lied to, kidnapped, or duped into signing false labor contracts.

In some ports, far from the arm of Chinese law, barracoons, not unlike those that dotted the African coast, were erected to hold the vulnerable males and they were monitored by armed guards. Approximately three-quarters of a million men and boys ended up in the “coolie” trade.

Richard Henry Dana, author of Two Years Before the Mast, while in Cuba, witnessed the selling of males in the marketplace. He wrote that the price paid for a Chinese laborer was $400.00.

The sailings of American vessels, carrying from 244 to 500 souls each, were plagued with disastrous events. Many Chinese rebelled against their captors. Numerous Chinese died from being fired on or kept secured in the hold of ships and suffocated. Many became lost in tumultuous weather, and untold numbers died before they could outlive their service. The case of the Robert Bowne, the most documented “coolie” ship and throughly developed in this book, provides particular insight into the deadly trade.

America’s Role

In my studies, I identified thirty one American vessels involved in the trade. Many of them were famous clipper ships of the period, Swordfish, Sea Witch, Winged Racer, and Live Yankee. In addition, there are at least 116 more American ships under sail that were tallied by a port official in Cuba. Add to that incredible number those vessels that brought human cargoes to the Chincha Islands of Peru, Brazil, Panama, Mauritius, and others. As the trade became more disreputable, Western nations gradually withdrew, and the Americans who participated became major transporters.

Even then, my tabulation of the ships involved is assuredly incomplete. The ocean can never reveal its dead: those ships that shipwrecked, those Chinese who rebelled and were killed, those vessels that had registered false names at ports of arrival, those captives who committed suicide where they labored or became sick and useless on board and were thrown into the sea, the vessels that ship owners managed to keep out of Lloyd’s Register of Ships, and those Chinese who would never grace a ship’s passenger list, or have a death certificate signed for them, nor would so many be remembered for their presence, trapped forever in that malevolent trade, would never be known.

“Coolie” activity commanded profits that were staggering for the time: an approximate $300 million was earned overall; the Americans share was an approximate $140 million or the 1988 equivalent of approximately $1.5 billion [or 2014 equivalent of about $3 billion, using the CPI to adjust]. The number of American voyages more than likely approximated 900 over the period, requiring a remarkable movement of vessels for any time.

The ships under sail transporting Chinese immigrants to California in particular, loaded their human cargoes with little concern for the comfort of their passengers. Charging as much as the passage would allow, ship owners earned unprecedented fortunes. The same conduct carried over into the transportation on board the great transpacific steamships that began to monopolize the route between China and the United States. The two foremost steamship lines were the Pacific Mail and the Occidental and Oriental, registered as California corporations.

American politicians, unions, and newspapers, particularly in the West, concentrated their scorn on what they considered an inseparable triad: the “China ships,” as the transpacific steamships were called, the Chinese passengers who traveled in them, and the Chinese crews that manned them. Immigrant, ship, and sailor bore the bitter attacks of slander and hatred.

Antipathy toward Chinese culminated in the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Tightened restrictions of the Act continued well into the 20th Century.

Concluding Thoughts

The seeds of failure for a prosperous China Trade were being planted during the years in which western nations treated China as a semi-colony, taking as much as they could get and giving little or nothing in return. The failure was also precipitated by the nations in which Chinese nationals were exploited for their labor, but denied universal rights and protections.

The story of Commissioner Lin Tse Hsu and his destruction of the great quantity of opium in 1839 is as important to Chinese history as the Boston Tea Party is to the United States; and although Lin’s actions precipitated defeat by the Western powers, the national humiliation China and Chinese suffered for almost a century is partly responsible for the two revolutions in modern times. With an emphasis on its own needs, China will assuredly measure each petitioner for respect. That nation’s history also suggests the need to be especially aware of challenges to its sovereignty.

This post written by Robert J. Schwendinger.

Thanks. Interesting, albeit repulsive and shameful history. This post is a nice follow-up to one of Menzie’s recent post on birthright citizenship. During the 14th Amendment debates there was a vigorous argument over specifically excluding native born Chinese from birthright citizenship. This short history goes a long way towards explaining why ethnic Chinese were being considered for exclusion of birthright citizenship.

Is the history of Western Civilization, or the human race, any more repulsive and shameful than the recent record of human rights in China?

And, should the civilized world allow China to annex 90% of the South China Sea, like Russia annexed Crimea?

You should pay more attention to US human right records in ME and at home. As to SCS, you could ask on what basis a country is entitled to own something in SCS. Perhaps then you understand the SCS disputes better.

You don’t seem to care much about human rights.

I’m sure, China feels entitled to Taiwain too. The basis of dismissing other countries claims in the SCS and ignoring international laws isn’t the best way of settling disputes.

China human right records have been improving by leaps and bounds. One just needs to look at the hundreds of millions being lifted out of poverty over the last few decades, high level of education, 100% housing, health and social cares. China is well aware and it is working very hard to always improve on governance and societal fairness. US should concentrate on working how the blacks are not easily gunned down by triggered happy cops, cutting back on drone attacks that often wipe out wedding parties, hundreds of thousands innocent deaths from aggressive wars of invasion based on lie by US in foreign countries.

Which international law says Taiwan is not part of China? Could you elaborate on what basis China dismiss other claimants in SCS and which international China ignores? Do you know also on what basis other claimants dismiss China’s claims likewise?

China has very poor human rights (for example, go to Wikipedia and see “Human Rights in China”). If they’ve been improving by “leaps and bounds,” it’s hard to imagine how they were before. Anyway, if you’re using economic progress as the measure of improvements of human rights, the U.S. is way ahead of China.

There’s no U.S. policy to systematically shoot blacks or kill innocent people. Also, the U.S. isn’t taking over countries territories. The U.S. works with its many allies to improve conditions for the world’s population, which includes neutralizing destructive elements.

And, I’m not surprised you believe China owns Taiwan, along with all the disputed parts of the SCS. For example, go to Wikipedia and see “Spratly Islands Dispute,” in case you don’t believe there’s a dispute.

The question in the SCS is power and legitimacy. These are two different things. Power is useful when all interaction is conflict. A lion does not need to negotiate with a gazelle.

However, when relationships contain both adversarial and cooperative elements–the latter, for example, related to the trade and investment, in turn implying the free movement of goods, money, information and people–then there is a related need to mediate conflict. As I have said before, it’s hard to trade with people you are threatening militarily.

The solution calls for China to step up as a true hegemon. This will secure for China almost everything it wants, at much lower cost, and with much higher prestige and international standing.

I’ll be in the Beijing area in late November, and I’ll try to find a venue to make a presentation on the topic, if there is interest.

The title will be something along the lines of “How to make friends, influence people, and squeeze the US out of East Asia”.

China needs to separate usage from ownership. And it needs to act as a true regional hegemon.

The just concluded xiangshan forum 2015 in China where defence ministers and military leaders from 49 countries and many institutions and experts from around the world discussed mainly defence and security issues in Asia would be a good place for your input.

I’d really prefer an all-Chinese audience. It’s an internal Chinese matter, from my perspective.

I’d be looking maybe for an academic venue, or maybe foreign ministry, something like that–a setting where participants feel comfortable asking me questions.

In any event, I’ll see what I can find.

I notice the frequency of Scott Walker themed posts diminished after he ceased to be a factor in the Presidential contest.

PeakTrader: “And, should the civilized world allow China to annex 90% of the South China Sea, like Russia annexed Crimea?”

Hey, is that you, Jim Webb?

Father in law?

Steven Kopits: Yes, I am fortunate that my father-in-law is an authority on the subject.

By the way, I thought the post was really well done.

I do not think you are sincerely concerned about human rights in China but rather you are just interested in getting a few kicks out of gratifying your own superiority complex. One does not need to look much further to have an idea how US human records have been like then just knowing the facts that African Americans were still hanged from trees or towed behind trucks in the 1960’s and just to add that the inhuman ways laborers from China were treated in US as touched upon in Menzi’s article here.

As I understand US and China mutually issue a human right report annually about each other’s human right status. As far as I know there are about the same number of pages and no one hears any denials from US govt about the contents of such report from China.

In case you were not aware, US were involved in more than a dozen wars since ww2 that caused many millions of deaths. The recent wars have also been causing hundreds of thousands of refugees problems with EU bearing the blunt from the craps left behind by US aggression. Such is the contribution of US to human rights, peace and stability of the world.

By the way, there is also no policy nor is it in the constitution of PRC to violate the human rights of people in China.

As to Taiwan and SCS, you would do better to inform yourself better first before you spill your ignorance.

Of course, it’s hard for you to believe Americans sincerely care about universal human rights, since your propaganda, which includes blowing some things out of proportion and minimizing or ignoring other things, shows Americans are no better than Nazis, Imperial Japanese, Soviets, Communist Chinese, North Korea’s government, other communists, dictators, and terrorists, along with believing China has a right to take over the SCS and Taiwan, regardless of other countries rights.

You bashed China and I countered. I think it is fair. Many parties think they have right to claim SCS in part or whole. So why only China’s claim bothers you?

Easy, Ben.

I find my Chinese friends just now are quite conflicted, indeed, beleaguered. Almost without exception, the Chinese I know are decent, hard-working, well-educated people. The Chinese as a race are highly socialized–the pressure to be a good son or daughter is immense, and something the Chinese take very seriously, I think. In such a culture, it’s hard to be the bad boy. It causes a lot of internal turmoil. And that’s also true of China in the South China Sea. It is like the star student smoking joints with the playground bully. China as the aggressor doesn’t fit.

At the same time, my Chinese friends feel that China is being unfairly picked on the in the SCS, as all the other adjacent nations also have outrageous territorial claims, but only China is being beaten up in the press. And that’s true. But it’s also beside the point. If Vietnam makes outrageous territorial claims, we all have a good laugh. If China makes outrageous counter-claims, then we see a regional arms race and the US and China risking a totally unnecessary (and more to the point, unseemly!) conflict in the SCS. China has to play the role of hegemon, but its citizens feel weak, that they are being unfairly ganged up on. When a fundamentally strong country feels weak, that is a very dangerous thing. If the strongest kid in school feels that everyone is picking on him, then someone’s going to get hurt on the playground.

So how does a hegemon behave? Let me give you an example. The US and Canada have certain territorial disputes along our maritime borders. Now, the US could order the Navy or Army to seize the disputed areas. Canada could not stop us. But Canada would immediately seek allies, very possibly the Chinese. So China could find itself drawn into an all-American dispute in which it really doesn’t have much upside either way. Why doesn’t this happen? Because the Canadians are entirely confident the US would never use force to resolve the dispute, and instead it will come down to haggling, name calling, lawsuits and the like, and over time, some agreement will be reached. So, the US is fundamentally a hegemon which could achieve its Canadian goals by force. But the country would never be trusted again. Thus, such disputes will tend to be handled as commercial, diplomatic or legal issues–military force or the threat of it never enters the equation. The US, despite vast military superiority, is forced to act with Canada as though its army and navy didn’t exist! The US is compelled to abide by an abstract set of property rights which, as a practical matter, it could violate by force. But it doesn’t.

When international relations have both conflicting and cooperative aspects, there will arise a need for a body to establish and enforce property rights. In territorial matters, there is no supranational body capable of filling such a role. Therefore, it falls to the strongest country in the group to provide such services, that is, a kind of provision of international public goods, including adjudication of territorial claims, protection of international property rights, and physical security. Thus, the US is often called on to intervene in places like Iran and Syria, because stability is hard to find without American involvement. Thus, if the US fails to act as a legitimate hegemon in, say, Iraq, then a void is created which can be filled with the likes of ISIS.

Note, however, that the hegemon is constrained–just as I illustrate above. President Obama would like to stay out of Iraq and Afghanistan, but we keep getting sucked back in. Germany or Canada can afford to walk away. If the US does, everything goes to hell. Thus, in some cases we cannot resort to force. In other cases, we are compelled to use it.

Note also that the hegemon does not regulate domestic matters, functionally speaking. In providing stability for trade and investment, the hegemon will tend to be a status quo power. We will pretty easily line up behind dictators if they permit the conduct of daily business otherwise. “The spice must flow!” to quote Frank Herbert. That’s really all we care about (at least if you’re on the right.)

The hegemon faces a principal-agent problem, in this case, on the national (group) level, rather than the individual level. For example, in the Iran negotiations, the US is both leading international interests, as well as pecuniary US interests, for example, the protection of Israel. This conflict, as all principal-agent conflicts, often remains not entirely resolved. Doing well and doing good are always intertwined, and it’s not always clear which will win out. Sometimes we are supporting the system as a whole; sometimes we are pursuing American interests. There is no permanent, clean divide.

This principal-agent problem also shows up in the ‘realist’ versus ‘idealist’ pressures on foreign relations. Republicans tend to the realist side: we’re comfortable with Bangladeshi sweatshops and Middle East dictators. As the operator of the international system, our obligation really extends only to inter-state issues, notably related to security and trade. By contrast, Democrats typically want to extend the franchise to cover domestic issues like human rights and environmental issues. They see hegemony as extending to intra-state issues. So that tension, as you point out, is real. We’d like a Swiss democracy in Syria, but as a practical matter, we’d settle for a solution which prevents terrorists from attacking New York. In many cases, such tensions are never fully resolved, and they won’t be resolved for China, either. Welcome to the club.

Most importantly, China does not have the luxury of thinking of itself as the same as Japan, or heaven help us, Vietnam. China has special responsibilities, and these will allow you special privileges, but also constrain your options. Vietnam has the luxury of making ludicrous territorial claims. China does not.

On the other hand, China can organize the system, and it will receive associated benefits. For example, if China acts as regional hegemon, it will find itself in the position to adjudicate disputes between, say, Japan and Korea. And that will make you feel superior indeed. Smug, in fact. It’s great to be the hegemon.

So, you need to move beyond your identity as a principal in a conflict, as one country among many in the region. China must step up and adopt the role of agent–regional provider of public goods–even though at times this will conflict with–and indeed, trump!–your interests as a principal.

It’s not that hard. The Chinese have all the tools–excluding the self-confidence–to do this. That last element is not so difficult to find.

If the communist Chinese feel “conflicted” about bullying its weaker neighbors, why do they keep doing it?

I agree, they should behave differently. However, the way they’ve been behaving has been so effective. The Spratly Islands is a done deal and they can get the rest of the SCS and Taiwan, except for those annoying countries like the U.S..

If the civilized world continues to tolerate bad behavior, there will be more of it.

Steven, Thank you for your kind comment. I hope authorities in China take note of your good input.