I wanted to go to this Society of Government Economists (SGE) event, with Prof. Tara Sinclair (GWU) and Chad Stone (CPBB), but I’m in the Midwest… Fortunately, they shared their thoughts with me.

Professor Sinclair’s slides are here. She addresses three questions:

- Are we in a recession now?

- When is the next recession coming?

- What will the next recession look like?

On point 3, Sinclair notes that the next recession, whenever it comes (and we’re unlikely to see its onset) is potentially going to be a self-inflicted wound:

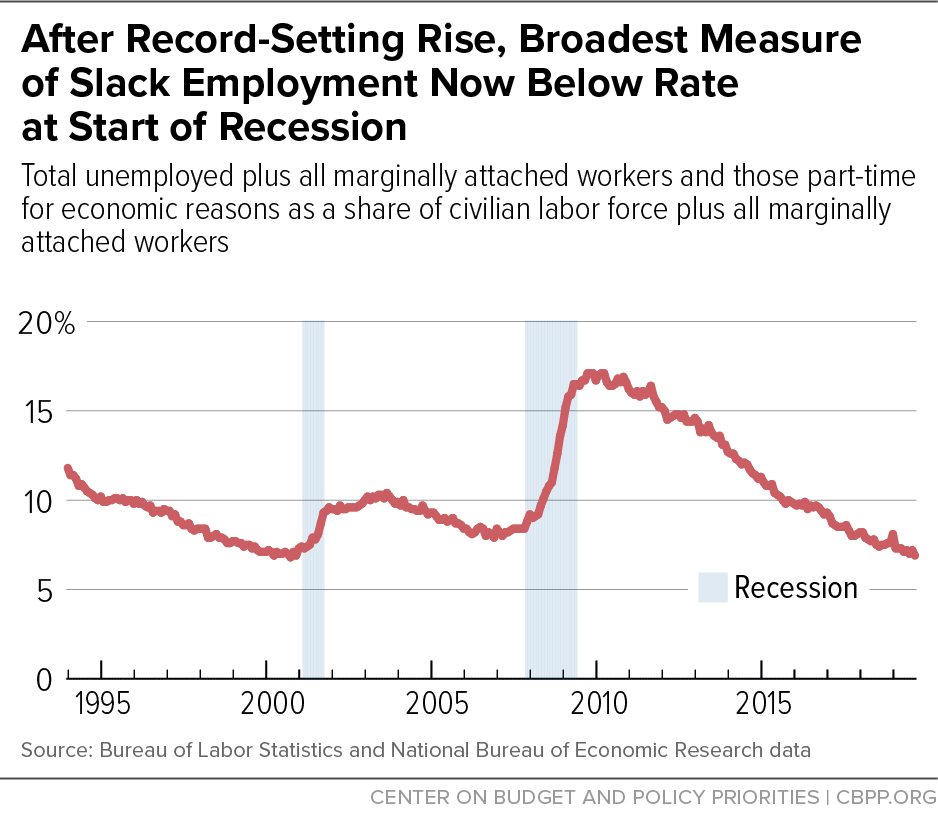

Dr. Chad Stone discussed how the onset of recessions — and hence the time for action — is typically signalled by a rise in the unemployment rate (as shown in the CBPP post-Great Recession chartbook).

In anticipation of the recession, however, it makes sense to put into place automatic stabilizers, as proposed by the Hamilton Project in their recent paper. That’s in part because it’s unlikely discretionary fiscal policy can be implemented with sufficient rapidity if the recession is of short to moderate duration.

Unfortunately, the policy thrust of the current administration is exactly in the opposite direction — for instance cutting, rather than enhancing, SNAP.

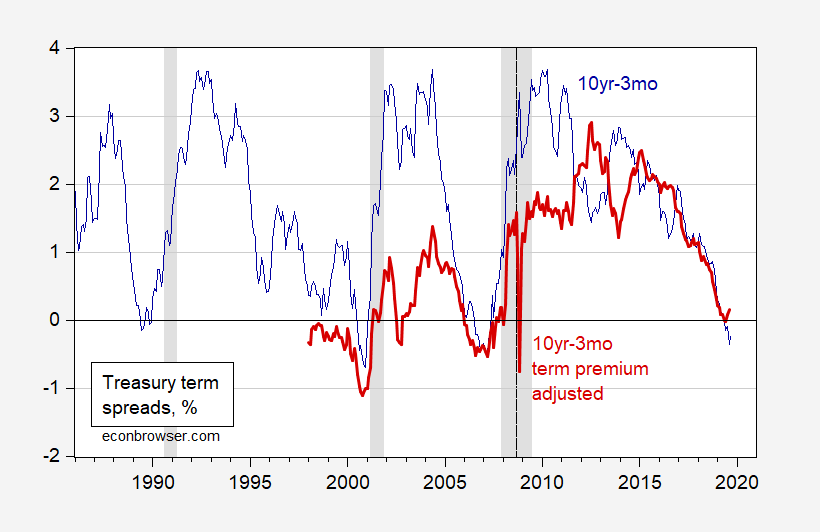

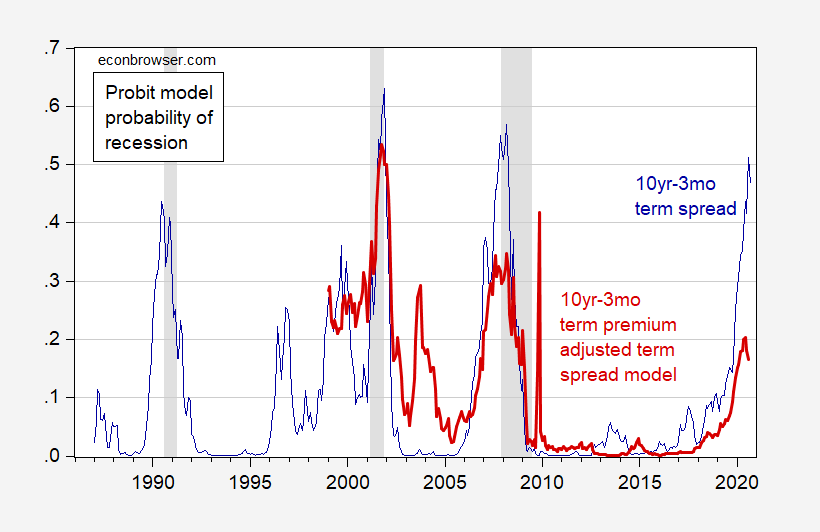

Here’s my assessment of the likelihood of recession, based on the yield curve:

Figure 1: Treasury 10yr-3mo spread (blue), and 10yr-3mo spread adjusted by estimated term premium (red), in percentage points. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: Fed via FRED, SF Fed, NBER, and author’s calculations.

Figure 2: Probability of recession from probit model using Treasury 10yr-3mo spread (blue), and 10yr-3mo spread adjusted by estimated term premium (red). NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Source: Fed via FRED, SF Fed, NBER, and author’s calculations.

We are once again the benefactors of Menzie’s friendships in his field of expertise. Please pass on thanks to Menzie’s collegial friends.

This is unrelated, but in the big picture you might say it is suitable for our times. I obviously did not create it myself–but I think the person who posted this won the internet on October 7th, 2019:

https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Mueller/comments/devhif/when_trump_claims_to_fight_corruption_or_drain/

This seemed so extreme, at first I thought it must be the left-wing version of FOX news. But with all the tweets and links attached, this appears to be 100% accurate. How much longer are we going down this road so Mitch McConnell and Lindsey Graham can feed our 200+ years nation to the wolves??

https://www.rawstory.com/2019/10/like-a-kamikaze-pilot-destroying-america-experts-outraged-after-trump-quietly-moves-to-pull-put-of-treaty-for-monitoring-russia/

https://www.businessinsider.com/us-pulling-out-open-skies-treaty-report-2019-10

This is the REAL traitorous behavior. You know if Menzie wasn’t on filtering duty I think I’d have some more words for this.

Moses,

I am in complete agreement that this matter of Trump planning to cancel the Open Skies agreement is really seriously awful, more awful than his letting the Turks invade northeastern Syria to crush our former allies, the Syrian Kurds, which is also plenty awful, with both more awful than his stonewalling the impeachment inquiry, which is just what we would expect from him, but with this latter dominating both of those other stories.

Really, with this sort of stuff going on, the GOPsters should start thinking seriously about the 25th Amendment, although quite a few of them support him on the Open Skies matter for reasons I do not understand other than just knee jerk supporting the military-industrial complex. But many of them are not on his side regarding the Turkish-Syrian-Kuridish matter, indeed are horrified by it, as they should be.

JBR,

Open Skies is an operation I have little knowledge of and not much opinion one way or the other.

Anti Ballistic Missile treaty was annulled to keep spending on many fronts including that 3 stage rocket in silos in Alaska and California which does not carry a working kill vehicle. Follow the money on ABM.

Intermediate nuclear forces (INF) withdrawal enjoys counter charges of “cheating”. SM 6 (interceptor missile) launch tubes can fit INF range cruise missiles, and they are on the way to Rumania and Poland. The operational advantage of having the kind of weapons fired from Montana in UK and Belgium is a reason to go away from INF treaty. As well as follow the money! Also US can now place INF range systems in the west Pacific.

My view of the Turkey (NATO country) invasion of NE Syria is “no point in telling Turkey to refrain from crossing or bombing across the Yalu….” US policy has appeared to ignore the borders of any country when it fits the “plan”.

US arming the Kurds appears to Erdogan same as Stalin arming Mao appeared to Chiang.

Moses….

“traitorous behavior”, interesting. How do you define traitor in absence of war?

Lately, it seems that any act in favor of the republican who beat Clinton is “traitorous behavior”.

ilsm: Gee, what happened to the Rosenbergs?

There’s a lot of debate about vaping, and a lot of teens are vaping now. I have my own opinions on it. Here is a recent paper discussing the relative risks vs “old school” traditional cigarettes (tar included):

https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/366/bmj.l5275.full.pdf

Hmmmm, Copmala at 2% in this poll. Well, no need to worry, Barkley says she’s gonna kill it in South Carolina. Plus she’s a big fan of Tupac music from the early ’80s, so you know when she was bussed to the white school near Berkeley “she was down with the homies”.

https://i.redd.it/ul79bq4ml9r31.jpg

BTW, Is Wisconsin a province in Canada??

Here is what Trump thinks of all of this:

“As I have stated strongly before, and just to reiterate, if these economists do anything that I, in my great and unmatched wisdom, consider to be off limits, I will totally destroy and obliterate the Economy of the United States (I’ve done before!).”

Off topic but timely. The House Intelligence Committee has issued this subpoena to the Pentagon as well as the OMB:

https://intelligence.house.gov/uploadedfiles/2019-10-07.eec_engel_schiff_to_esper-dod_re_subpoena.pdf

Its timeline of events detail the key points in UkraineGate. Trump is a liar and a traitor so yea impeach the clown.

Axios covers this with a picture of the OMB director Mick Mulvaney mulling how he can be more of a Trump sycophant.

https://www.axios.com/pentagon-office-of-management-budget-ukraine-investigation-b61746d0-8355-4d98-9de5-77d53c6ca667.html

Donald Trump to Darth Schiffty:

“If you impeach me, I shall become more powerful than you can possibly imagine.”

No Ricky Sycophant Boo. Trump is Vader. Pelosi is Princess Lea! Maybe you were drunk when you watched Star Wars!

Hey Rick – your coalition of sycophant and traitor enablers is showing cracks. New poll on the question of both impeaching and REMOVING Traitor Trump for office is out. Percent of Democrats who have seen the light = 78%. But here’s the news that should send shock waves through Faux News. 18% of Republicans have seen the light.

Yea I know you are trying your best to lie to the public. It is not working any more. Sorry dude – it is going to become an increasingly lonely island to stand on as you defend our Traitor in Chief!

ahh, dick striker returns. he who believes that it is permissible to lie to achieve ones goals. now it appears rick stryker believes the president is not beholden to the other branches of government. rick appears to possess the mindset that president trump should be treated more like a dictator, or emperor, who should never be challenged because he is never wrong. funny how dick used to rail against obama for executive overreach. that is all trump has done. and states rights? apparently those rights should not be extended to california, because in trump world the fed (ie central government) can override any state solutions to their problems. fascinating how hypocritical this little critter dick striker has become.

Trump’s boy in Scotland – Gordon Sondland – was supposed to testify to the relevant House committees but it seems Sec. State Pompeo has decided to obstruct the investigation of UkraineGate:

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/sondland-house-testimony-ukraine-trump-impeachment

Of course the mobsters in the White House would prefer to rub out any potential witnesses so maybe Sondland should start watching his back.

There’s a whole lot of noise in the signal these days. I’m not sure how you would calculated the probability of anything using the data at hand. It goes every which way. My take is that we are at a peak, and we will see much slower hiring next year. I still don’t know if it will result in a full-on recession or just a sticky soft spot. But, there’s too much negative data to go along with the positive for 2020 to be boom times. I don’t see a ghost of a chance that there will be any kind of resolution with China. Plus, erratic diplomatic behavior will throw wrenches into other things that will cause economic problems here and abroad.

What a mess. I don’t remember who it was who said Americans always do the right thing after trying everything else. We were trying everything else as an electorate in 2016. Now maybe we will do the right thing.

This is exactly what I’m talking about. From Yahoo Finance:

Fed’s odd dilemma: Low unemployment but pressure to do more

WASHINGTON (AP) — With the nation’s unemployment rate at its lowest point since human beings first walked on the moon, you might expect the Federal Reserve to be raising interest rates to keep the economy from overheating and igniting inflation.

That’s what the rules of economics would suggest. Yet the Fed is moving in precisely the opposite direction: It is widely expected late this month to cut rates for the third time this year.

Welcome to the strange world that Jerome Powell inhabits as chairman of the world’s most influential central bank. Though unemployment is low, so are inflation and long-term borrowing rates. Normally, all that would be cause for celebration. But with President Donald Trump’s trade wars slowing growth and overseas economies struggling, Powell faces pressure to keep cutting rates to sustain the U.S. economic expansion.

“It’s a very hard position for the Fed to be in,” said Diane Swonk, chief economist for Grant Thornton, a consulting firm.

When Powell speaks Tuesday afternoon at an economics conference in Denver, his remarks will be scrutinized for any hints of the Fed’s next steps.

One illustration of the Fed’s unusual dilemma: The unemployment rate is now 3.5%, the lowest level since 1969. The Fed’s benchmark short-term rate stands in a range of just 1.75% to 2%. By comparison, the last time unemployment fell below 4% — in 2000 — it raised its key rate to 6.5% to try to control inflation, which normally rises as unemployment falls. Having its benchmark rate that high also gave the Fed room to cut rates once a recession hit the next year.

Today’s economic landscape is dramatically different. The same forces that are depressing growth and inflation and limiting pay growth are also boxing in the Fed: Slowing population growth and sluggish worker productivity are restraining the economy’s ability to expand.

Online shopping, international competition and a more frugal consumer have held down inflation. A weak pace of growth and undesirably low inflation have forced the Fed to keep borrowing costs historically low. Once a downturn inevitably strikes, the Fed will have little ammunition left in the form of further rate cuts.

Persistently low interest rates are “the pre-eminent monetary policy challenge of our time,” Powell acknowledged in June.

In response, the Fed has embarked on a far-reaching review of its monetary strategy and tools, which includes a series of public consultations known as “Fed Listens.” Its initiative is a tacit acknowledgement by the Fed of its peculiar economic quandary.

“Fed Listens” sessions have been held by nearly all of the Fed’s 12 regional banks. The sessions, attended by high-level bank staffers and sometimes Powell himself, have included labor advocates, community groups and academics specializing in worker training and education. The Fed says it will announce any changes to its strategies in the first half of next year.

One likely change, Fed watchers say, is the adoption of an average inflation target that the Fed would aim to achieve over time. Since 2012, the Fed has set an annual target of 2%. But it hasn’t always been clear whether that is a ceiling or a more flexible goal.

Central banks around the world began adopting inflation targets in the early 1990s to help keep a lid on prices. Yet now most of them are struggling to reach their limits. Since adopting 2% as a target, the Fed has missed it nearly continuously, with annual inflation averaging just 1.4%, according to the Fed’s preferred measure. In August, for example, U.S. prices excluding volatile food and energy costs rose 1.8% from a year earlier.

An average target would require the Fed to let inflation run above 2% to offset those times when it fell below the target. Otherwise, businesses and consumers would start to expect permanently lower inflation.

Those expectations can turn into reality: Businesses may, for example, respond by providing smaller cost-of-living pay raises, thereby making it even harder for the Fed to boost inflation. (The Fed seeks a low level of inflation as a cushion against a destructive fall in wages and prices.)

Supporters of average inflation targeting argue that it would help the Fed meet its objectives. Charles Evans, president of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank, appeared to support this view in a speech last week.

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/feds-odd-dilemma-low-unemployment-101119772.html

*****

If you don’t understand demographics, you won’t be able to make sense of the Fed’s dilemma.

You are now citing Yahoo Finance??? OK – that was a LONG discussion none of which raised “demographics” but some idiot who happens to live in Princeton (but has been denied access to the local campus) writes this one liner???

‘If you don’t understand demographics, you won’t be able to make sense of the Fed’s dilemma.’

No Stevie pooh – you do not understand either demographics nor basic macroeconomics. So could you give us all a break and just go away? DAMN!

Here is a question for you: If the effect of tariffs is to cause a rise in prices early next year, should the fed raise rates to counteract the resulting inflation? I don’t see a practical answer to that at all.

Willie, it would depend on whether they believe it wil affect underlying inflation not just the headline rate

How do you figure that out when the guy with his thumb on the button lurches around like a BB in a tin can? Nobody knows whether he will slap on more tariffs or not. Including him, until he does it and then maybe undoes it the next day.

one way to figure it out is to determine whether the producers want to take a hit on profit margins and keep market share or not.

If they do you wait on raising rates. It they will not they you act.

What stage of the business cycle and how competitive your economy is is quite relevant.

For example our Central Bank has not worried too much when our exchange rate falls as profit margins are lower

steven, you are not looking at the problem correctly. this is not a problem for the fed, ie demographics. the fed deals with monetary policy. demographics are not part of that equation. if the nation wants higher growth and inflation, then we need better fiscal policy. the experiment has shown its results around the world. under current conditions, lower interest rates do not really spark growth and they do not spark inflation. fiscal policy, in the form of government spending will. at these low rates, why wouldn’t we invest in several moon shots for the future? steven, this is not as complicated as you imply. if you want to find blame, look at congress and the president for failure to provide an appropriate spark. trade wars are simply a negative version of fiscal stimulus. that is what we have gotten thus far.

“…this is not a problem for the fed, ie demographics. the fed deals with monetary policy. demographics are not part of that equation…”

I think you’re correctly capturing the Fed’s mindset, Baffs. I am arguing that, in fact, demographics do matter. Why? What drives the demand for goods and services, chief among them real estate? Demographics. Real estate appreciates if there are more people chasing a fixed supply. No one borrows money to buy a car assuming that it will appreciate in value. On the contrary, it has been all but religion in the US the value of dwellings will rise over time. Now, if demand is falling, shouldn’t prices also be falling, or something close to it? Doesn’t fixed supply with falling demand work exactly the reverse of the way it has since, well, probably going back to the early days of the republic?

If demand for housing is falling and the demand for manufactured goods is also flat to falling, what are the implications for credit markets? What percent of debt is used to fund growth? A big percent. And what interest rate would you pay for your house if you assumed it would be worth 30% less when you come to sell it? So we have some reason to believe that demographics will influence both the demand for goods and price level. Further, we have reason to believe that an aging society may have a diminished demand for debt, and therefore lower interest rates.

Now let’s take a look at unemployment. In a young, fast-growing market, you’ll have to make room for new market entrants before they create demand for their own goods (ie, have a salary to spend). You’ll constantly be trying to fit them into a system where they weren’t needed yesterday, and that could well create higher levels of unemployment.

By contrast, in a society with a declining workforce and a rising number of retirees, the logic is just backward. Nowadays, when a person retirees, their consumption declines by about 1/3 (if I recall correctly), but their production declines by 100%. So as an employer you’re under pressure to find someone to replace 2/3 of the person who just left at a time when the increase in the workforce is substantially less than the number of persons retiring. This will tend to push the unemployment rate down — but note that it does so without inflation because demand in aggregate is flatish to falling at the same time, but the workforce is falling faster. (We can adjust this argument for increased productivity. For now, let’s assume productivity growth is set to zero.)

This gives us an economy with low GDP growth, low interest rates, low inflation, and very low unemployment. So to Joseph’s point (I think it’s Joseph), your whole NAIRU calculation goes out the window in a changed demographic environment. Low unemployment does not lead to high inflation at all because aggregate demand remains tepid. How can you form a price bubble in an environment where demand is flat to down? But that then indicates that maybe you don’t see business cycles very often, if you believe, as I do, that bubbles arise when the increase in fixed assets are unable to keep up with increased demand (ie, the lag from order to delivery for fixed assets creates the business cycle). That doesn’t happen in a demographic environment like the current one, or at least it may not. But you’ll frequently see ‘recession-like’ effects because the decline in the workforce is fairly closely balanced against increasing productivity. That’s my concern about recommendations to reflate Germany. Are we seeing a recession, or merely ‘recession-like’ symptoms arising from demographic decline exceeding productivity growth? Right after Menzie’s post, Germany’s unemployment rate declined by 0.2 pp.

In this context, traditional fiscal stimulus doesn’t work. What can you stimulate in a full employment economy? Not much. Japan has run up a debt-to-GDP ratio over 200% and Japanese growth remains anemic–and yet unemployment is the second lowest in the OECD at 2.4%. As it must! If the economy is at full employment, the only possible impact is on productivity growth, and frankly economists know very little about how to stimulate that. So instead you create a kind of Ponzi scheme where deficit borrowing essentially goes to buy off a bunch of constituent’s political needs. That’s clearly the story of Japan. This is the future that hard-money Ken Rogoff warns us about (with which I agree, btw).

The only thing you can stimulate with fiscal policy is the fertility rate, since GDP = number of workers * output per worker, and GDP growth = change in the number of workers * change in output / worker. Now, growth of output / worker in an old economy — old dogs, new tricks — could be pretty tepid. But maybe it holds up. However, if the workforce is declining as fast, then GDP growth may be close to zero even though productivity growth is decent. But if you want to pick up the growth rate, you have to increase the number of workers, and that means primarily the fertility rate (with some potential contribution from immigration). That’s where you can apply fiscal policy, as is being done in Hungary, Poland, Russia and France.

So, yes, I agree with you that macroeconomists see demographics as outside their domain. Consequently, there’s a tendency to try to force the rules-of-thumb and economic models from the 1980s – 2000s on the current environment. That’s why John Williams says he’s surprised unemployment could go so low. If he had worked through the Japan numbers (happy to send you the spreadsheets), he’d see very clearly what’s happening. And that’s true for Jim or Menzie or Ken Rogoff or Jeff Frankel. Spend two days and work through the exercise. It would change the understanding of the macro environment.

Steven Kopits: Your arrogance and ignorance are both astounding. As someone who taught Eggertson and Krugman and other papers dealing with demographic transitions in a much more sophisticated manner than you’ve done, I can tell you macroeconomists have long considered demographics. That’s why Williams worked on the natural rate of interest, for instance. Now, you may be right the FOMC and perhaps the Fed staff didn’t fully appreciate *how* the demographic transition would affect measurement of the unemployment rate and NAIRU, but the staff (i.e., the PhD economists) weren’t typically just working off rules-of-thumb.

By the way, you might want to look at the evolution of real GDP in Japan since Abenomics; and per capita real GDP growth vs that in the US. You might find it illuminating.

If WIlliams was surprised, then he hadn’t done his homework. None of Jim, Rogoff or Frankel used the word demographics.

But, ok, Menzie, you tell me the impact of a declining workforce on any of the following:

– inflation rates

– interest rates

– unemployment

– NAIRU (what is the current value of US NAIRU, in your opinion? why?)

– the business cycle

Williams has a 2% st interest rate against 4-5% he needs to deal with a recession. What should he do, when Jim’s work plainly suggests (as do a number of Fed studies) that QE is ineffective? Does the Fed have a ready toolkit for the downturn you seem to be searching for, or not?

Give us your view.

steven, worker productivity could be increased if a moon shot comes through. at worst, the fiscal spending would slowly grow the economy and create an uptick in inflation. you appear to want both anyhow. and if it results in a transformative economy, you got what you wanted organically from that point forward. worker productivity will not come from much more in the way of efficiency (unless you consider AI could improve efficiency, but at a significant loss of employment). productivity would come from unleashing the scientific and technological breakthroughs of tomorrow. today we get alot of talk but very little action on this. demographics have an impact, i do not dispute, but other issues are more impactful over the long run if implemented, in my opinion. for instance, productivity will never make great leaps if we continue down the path of energy from fossil fuels. the world is electric, and in the long run renewables and the like will give you much better opportunities than dirty and limited fuel sources which keep us in expensive wars.

Baffs –

“…fiscal spending would slowly grow the economy and create an uptick in inflation…”

Will it? That’s not clear at all. Japan has run up a debt-to-GDP ratio without creating either significant GDP growth or inflation. But the economy is, and has been, at very full employment by any traditional measure. This is exactly why I posed the question in the case of Germany.

“…worker productivity will not come from much more in the way of efficiency (unless you consider AI could improve efficiency, but at a significant loss of employment). productivity would come from unleashing the scientific and technological breakthroughs of tomorrow.”

Productivity is a very slippery concept. Productivity growth seems to come from many different sources and chug along at a more or less steady pace. That’s one reason economists have such a hard time getting a handle on it.

“…you appear to want both [economic growth and inflation] anyhow.”

There is no question that I am a sustainable growth guy. The primary function of government, in my opinion, is to create the environment for sustainable economic growth, yes. I am agnostic about inflation. I am literally asking that question: Should we have more inflation in a world of aging demographics? If you want inflation, then the history of Japan tells us that: 1) interest rates don’t work; 2) QE doesn’t work; 3) fiscal stimulus doesn’t work. So do we want inflation, or is deflation ok? If you decide you want inflation, you’d better line up some version of MMT, because that’s the only thing likely to work, in my opinion.

“…fossil fuels…”

Productivity arises from doing more with less. If I pay more for an electric car, and it does less, then by definition I am reducing productivity. The only way that’s not true is if you put a huge value of CO2 emissions, which I don’t.

“If I pay more for an electric car, and it does less..”

steven, you appear to lack any vision on where electric cars, or the electric society, will take us. oil and fossil fuels do not mix well with the future of electricity. how we will use it and store it are constantly changing in ways that mechanical systems driven by combustion engines are not efficient. autonomous and smart vehicles, for instance, fit much better with electric vehicles than gas engines. the cost to build batteries and electric motors has far more to drop than the equivalent gasoline and combustion engine. by your very definition, electric cars will improve productivity because they have (and will continue to have) far more capabilities than gas cars.

i am not sure you can qualify japan as a failure.

i have no problem with inflation if it appears. perhaps it hurts the elderly. it probably helps the younger generation. over the long term, should our policies favor the past or the future of the nation? i think it is a mistake to hurt younger folks to the benefit of older folks. where do you want to invest for the future of the country?

Baffs –

“steven, you appear to lack any vision on where electric cars, or the electric society, will take us. oil and fossil fuels do not mix well with the future of electricity. how we will use it and store it are constantly changing in ways that mechanical systems driven by combustion engines are not efficient. autonomous and smart vehicles, for instance, fit much better with electric vehicles than gas engines. the cost to build batteries and electric motors has far more to drop than the equivalent gasoline and combustion engine. by your very definition, electric cars will improve productivity because they have (and will continue to have) far more capabilities than gas cars.”

I have no idea what’s going to happen. Technology development, by its very nature, tends to be discontinuous and not amenable to traditional analytical approaches. Maybe EVs will dominate, maybe they won’t. I just don’t want to subsidize the solution and pick winners. Let the market work it out.

“i am not sure you can qualify japan as a failure.”

I am not sure I said that, but I do think running up a 200%+ debt-to-GDP ratio is a ‘failure’. On the other hand, it hasn’t killed Japan yet. I think the point is that a lot of the rules of thumb we use for growing societies are not the same as for declining societies. You can’t grow your way out of fiscal problems, for example.

“i have no problem with inflation if it appears.”

To be clear, we are speaking of allowing explicitly deflationary policies which puts the central bank within a small margin of the ZLB and thereby constrains its ability to cut interest rates in any ensuing downturn. The issue, therefore, is whether some measure of money printing would be warranted to maintain inflation around 2%, given that neither QE nor low interest rates seem to be effective in stimulating inflation. I don’t know the answer to that, but at a short term interest rate of 2%, I would probably want to form a view, were I a central banker.

“…it probably helps the younger generation. over the long term, should our policies favor the past or the future of the nation? i think it is a mistake to hurt younger folks to the benefit of older folks. where do you want to invest for the future of the country?”

Well, this is the main issue underlying everything, isn’t it? Our society has an elderly bias in SS and Medicare. We spend a large portion of our tax revenues on, in essence, maintenance spending on our elderly. This comes from taxes very often paid by families with children at a time when the fertility rate throughout the OECD is well below replacement. So should we redirect payments from the elderly to the unborn? They have in France, Russia, Hungary and Poland. It will be on the agenda in the coming decade.

Steven,

I am weighing in with what Menzie said, more or less. Sure, slowing population growth does tend to move aggregate macro variables in the directions you suggest, but also note that the US continues to have a higher population growth rate than most other high income nations, certainly way more so than Japan, which is apparently on the verge of making money on its massive national debt due to so much of it having negative interest rates on it. However, indeed US pop growth is slowing.

Menzie is right that one needs to focus on per capita outcomes rather than aggregate ones. This is what matters for living standards in a society, and on that measure indeed Japan is doing quite well, thank you.

My advice to you, Steven, is to stay away from macroeconomics. You are an expert on the oil industry and generally make at least well informed comments on it here. You also know a lot about migration and demographics, even though I disagree with some of your policy arguments. But when you start talking about demographics and macroeconomics, you start to get dodgy.

More generally, on macro you have a tendency often to simply fall flat on your face embarrassingly. If you insist on commenting on it, be more careful about what you post. Unlike some others here, I think you are a pretty smart guy and well informed on at least some subjects and even willing to be open minded on some matters many are not. But your comments on macro do not enhance your rep.

I made the points I did because no one else has made them. And I believe I have Menzie firmly pinned to the mat.

This question: “Williams has a 2% st interest rate against 4-5% he needs to deal with a recession. What should he do, when Jim’s work plainly suggests (as do a number of Fed studies) that QE is ineffective? Does the Fed have a ready toolkit for the downturn you seem to be searching for, or not?”

That doesn’t come from me. If you watch Jim’s interview with Williams, it is posed near the end by, I believe, an ex-Fed guy. I am merely repeating it here. Williams answered — and I encourage you to check this for yourself — something to the effect of “mumble, mumble, QE.”

And then Jim the next day in the comments section posts are very nice analysis of QE that shows each round was accompanied by rising interest rates. See the graphs. It’s right there. Convince yourself. So will QE work? Didn’t last time.

And then there’s fiscal stimulus, which the Japanese have tried for twenty years, the prime achievement of which was running up a huge debt-to-GDP ratio without materially generating either inflation or notable GDP growth. So it’s not at all clear to me that fiscal stimulus is effective in an aging demographic environment at full employment.

As for Jim: I refer you to his recession presentation. It’s splendid. And he concludes that investors used to want protection from inflation, now they seem to want protection from deflation. I think the numbers support that argument. But why? What has changed? Jim didn’t give us an answer, which makes me think Jim doesn’t have a model.

I am more than willing to defer to professional macroeconomists. But right now, I don’t see that the economics community has a model of how 2019 is different from 2004. I see the same rules of thumb being applied. When I was in graduate school, NAIRU was 6.5%. It’s clearly below 4% now, and may be below 3%. It certainly is in Japan. What do you think it is in the US? Why? If it’s not 6.5%, why has it changed? Is the concept valid at all in a setting with a declining workforce?

I have a coherent model that fits the data. That model came out of my Japan analysis, which is why I encourage others to work through the numbers. I am more than willing to say I was wrong. But I am throwing some pretty easy pitches over the plate, and no one has stepped up to take a swing, yet.

So why don’t you step up to the plate: Does the Fed have a complete toolkit for the next downturn?

Steven,

I do not know if you are addressing me or somebody else, but I shall comment a bit. In particular I shall note that I gave you too much credit on the matter of the relation between demography and aggregate macro variables. I agree higher population growth more associated with higher GDP growth. I also think there may be a link with the natural rate of interest. But for the rest of it, no.

On inflation and unepmloyment rates what we have is a relation between aggregate supply and aggegate demand. If population slows then both of them decline. We have fewer workers so less GDP growth, but also with fewer people there is less aggegate demand. So there is no clear link.

Regarding NAIRU, I have never accepted the concept. But it has no relation with demography. It is simply nothing.

On interest rate there is a possible link because a slower population growth raises the percentage of people who are old. Given that they borrow less, that might lead to a lower natural rate of interest.

But again, what happens to per capita income, no relation. Japan shows it, yes, slower aggregate GDP growth, but per capita GDP growth has done well.

I agree that various monetary tools are not all that effective, including QE. But this also has nothing to do with demography.

Barkley –

“On inflation and unemployment rates what we have is a relation between aggregate supply and aggregate demand. If population slows then both of them decline.”

No, they don’t. That’s the point. From now to 2029, the US 65+ population grows by 17 million. Given the US social safety net and retirement savings, consumption of this group falls only 1/3, thus it represents the equivalent of 12 million person’s consumption. By contrast, the 15-65 age group is forecast to grow only by 3 million during this period. (See the related CBO spreadsheet.)

Thus, per worker demand is increasing. with demand outstripping supply by around 9 million people equivalents. This should have the effect of pushing down the unemployment rate. At least that’s my read. The workforce is growing more slowly than the associated demand, but importantly, this does not lead to bubbles, because aggregate demand is not that strong. That is, a GDP growth rate of 2% understates the strength of the economy when adjusted for inter-cohort dynamics.

*****

NAIRU. Well, I am with you on that. I never liked it either.

*****

“On interest rate there is a possible link because a slower population growth raises the percentage of people who are old. Given that they borrow less, that might lead to a lower natural rate of interest.”

Well, how much lower? 0.1 pp or 4 pp? If it’s the former, who cares? If it’s the latter, you had better take a wholesale rethink of monetary policy.

*****

“I agree that various monetary tools are not all that effective, including QE. But this also has nothing to do with demography.”

So are low interest rates a problem for the Fed in managing monetary policy and the business cycle, or not? You just said above that demographics could lower interest rates. Or do you believe that interest rate policy at the Fed is irrelevant to the business cycle?

I think you’re trying to say that the Fed does not have an adequate toolkit to handle the next downturn. Is that correct?

To put in another way, assuming no productivity gains:

In the US, to 2029, for every 6 people who retire (turn 65), you need 4 new people to maintain the associated demand, but only 1 new entrant is available. That’s the demographic math. You think that gives you a tight labor market? I think so.

Kopits on a roll. Maybe its time for all people who will be under 50 by 2025 to be required to have 3 children, no matter the way.

Steven,

I might buy a short term easing of unemployment, but this should increase inflation. That is not happening. Your demography theory is not of any use for explaining what is going on with inflation.

OK, Barkley, so let me walk you through an illustrative, if imperfect, example.

Comcast employees thousands of people. Imagine that on a given day, six of them decide to retire. Now, these employees are also Comcast customers. However, when they retire, they cut back some on their cable, maybe they drop HBO to economize, but they still consume 2/3 as much Comcast services as they did the day before the retired.

Thus, Comcast will need 4 new employees (2/3 of 6 retirees) to provide services for those retirees, whose demand has eased, but by no means disappeared. However, the 15-64 age group is expanding only slowly, thus, only 1 new employee is available to fill those four open slots. Thus, Comcast has to make a series of decisions, one of which is to keep older workers longer, to bring in workers not traditionally in the workforce (in the case of Japan, this was women), and to hire more of those looking for a job. This later impetus will lead to a lower unemployment rate.

But note that Comcast sales, to the extent only one new employee is available, have actually declined. Demand is down by two customer equivalents (1/3 of 6 retirees), which is offset by one new employee. Thus, sales ceteris paribus are down 1 net customer, even as Comcast is struggling to fill its ranks and keep its employee headcount steady.

With demand falling, pro forma, Comcast’s prices should also be falling, Comcast’s borrowing requirements should be falling (compared to its historical norms), and it is certainly very hard to generate any kind of price bubble in this environment. Thus, when retirees are increasing faster than the workforce, and the growth of the workforce is low,, or even negative, then fundamentals will tend to create low inflation, low interest rates, low aggregate GDP growth — but also very low unemployment. They are all part of a package.

Now, this logic may be wrong, but it’s consistent with the data and a coherent model of itself.

Hungary fertility policy

Hungarian women with four children or more will be exempted for life from paying income tax, the prime minister has said, unveiling plans designed to boost the number of babies being born.

As part of the measures, young couples will be offered interest-free loans of 10m forint (£27,400; $36,000), to be cancelled once they have three children.

$36k is a lot of money in Hungary. And no income taxes for life? Wow.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47192612

Poland fertility policy

In 2015, Poland’s conservative Law and Justice Party proposed a plan called “500+ Families,” which would give Polish families 500 zlotys, or about $150, per month for every child they have after their first. For a family with three children, that’s about $300 per month in untaxed cash income, or about $3,600 a year—nearly double the amount of the U.S.’s new expanded child tax credit. Poland also has a child tax credit on top of this benefit. For single parents, or for children with disabilities, the benefit may be larger, and in some cases may be claimed for the first child as well.

The average wage in Poland is about $900 / month, so a boost of $300 / month is non-trivial.

https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2018/03/polands-baby-bump

Russia fertility policy

The Russian government has sought to encourage reproduction by providing financial incentives to women as part of its so-called maternity capital program, which currently provides mothers with a subsidy of around 453,000 rubles ($7,000) to help support their second child.

In February, Putin proposed expanding the program by giving mortgage subsidies to women who have three or more children. And there are indications more will be done.

The average monthly wage in Russia is about $700,

https://www.rferl.org/a/rising-mortality-rates-challenge-population-growth-decline-putin-demographics/29861882.html

“Maybe it’s time for all people who will be under 50 by 2025 to be required to have 3 children, no matter the way.”

We are now waking up to the reality that half of traditional GDP growth is generated by women having children — something which has been completely excluded from national accounts. So the question arises whether you care about declining population, or not.

If you do, it’s not possible to mandate people have children. You’d have to mandate marriage to do that, at a minimum.

Consequently, if you want more children, you have to pay for them. This represents then a kind of conservative feminism. “You want me to invest my time and effort in a child? Pay me.”

As we can see, the sums involved can be formidable indeed.

Steven,

I could care less what nationalist governments do on fertility policy This says zero about the economic arguments.

While having more retired people involves there being more non-working people buying stuff, a declining population means fewer young people who are also not working but responsible through their parents for more buying. Funny how you have said nothing about this part of the argument.

Barkley –

The comments on fertility were in response to The Rage about 8 comments up from here. But while we’re at it, historically GDP growth is about half population growth and half productivity gains. Given that we don’t really know how to speed up productivity gains, wouldn’t fiscal stimulus be better spent on increasing the number of taxpayers? If the government can borrow money at zero interest, it can easily hold long term debt. Wouldn’t the best use of such stimulus be to increase the tax base by having more children if you want to increase aggregate GDP?

Now, you may argue that a declining society is fine. It worked during the great plagues, for example (although Japan is on track to lose twice that amount as a percent of its population). After all, that’s the liberal line: it comes down to individual choice. I am happy to consider the pros and cons of that, but it matters for aggregate fiscal and monetary policy which way society goes.

Barkley –

I have no idea what you are trying to say:

“While having more retired people involves there being more non-working people buying stuff, a declining population means fewer young people who are also not working but responsible through their parents for more buying. Funny how you have said nothing about this part of the argument.”

Honestly, if you could take out a few double negatives, I’ll take a crack at answering your question. As for demographics, though, these numbers are as readily available to you as to me. Why are you asking me to do work which you could do as easily yourself?

Oh gag, Steven. You are coming across as just plain stupid here now.

For many of the macro variables what matters is the balance of aggregate supply and demand, which is tied somewhat to the proportion of the population working versus not working. A simple measure of this is to look at the dependency ratio, which is the ratio of those not working to those working, although this also depends on the setup of income flows and transfers to people of different ages.

Anyway, here is a chart showing total dependency ratio, young, and elderly for several nations from Wikipedia’

Country Total Young Elderly

Japan 64.0 21.3 42.7

US 51.2 29.2 22.1

Niger 111.6 106.2 5.4

UAE 17.9 16.3 1.2

I find your wording about a “declining society” somewhat misleading. If what you want is military power and broader socio-economic power internationally, then aggregate population and GDP are clearly important. If you are worrying about the quality of life of the people in a nation, then population is basically inrrelevant as it is per capita income that matters, something you seem to keep ignoring, even as both Menzie and I hace pointed it out to you, with Japan the obvious example. Its population is declining and its aggregate GDP growth is not much, but it has done quite well in recent years on raising its real per capita income. What really mattets here?

Your bringing up the plague is especially ihilarious. Most economic historians accept that real per capita incomein most of Europe rose quite a bit in the aftermath of the mid-14th century great plague. Check it out. Really.

And as for your Hungary, Poland, and Russia, these are nations whose motives are national power vis a vis other nations, not real per capita income.

If you want to use dependency ratios, ok, let’s use them. Do you think the level or the change in the level is more important?

Japan’s potential support ratio is 2.3 people aged 15-64 for every person 65+. Hungary’s is 3.9. What do you think the relative impact of these ratios is on unemployment, interest rates and inflation? Or is the change in the ratio which matters?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_dependency_ratio

“If you are worrying about the quality of life of the people in a nation, then population is basically inrrelevant as it is per capita income that matters, something you seem to keep ignoring, even as both Menzie and I hace pointed it out to you, with Japan the obvious example. Its population is declining and its aggregate GDP growth is not much, but it has done quite well in recent years on raising its real per capita income. What really mattets here?”

Well, some variables are individual, and some are aggregate. National debt is aggregate. Most fiscal programs reflect aggregate capabilities. Monetary policy is on an aggregate level.

From a personal level, what matters are 1) gross wages, 2) taxes and 3) aggregate price levels. With a declining population, unemployment should be low — or do you disagree? — and therefore wages should be high, just as after the Great Plagues. But against this has to be balanced a higher dependency ratio, the need for fewer workers to support a greater number of retirees with increased taxation. Also, existing national debt has to be allocated over an ever smaller pool of taxpayers. Is running up debt to 200%+ of GDP a good idea? Can a society within minimal GDP growth ever get out from under such debt, or is default — and perhaps a collapse of democracy — only a matter of time?

Aggregate price levels should also be falling — but then here’s that question again — should that be allowed? What are the implications for monetary policy?

You may embrace the nihilism of a society consuming itself. I do not. Those who reproduce will, in no more than four generations, displace those who did not. Those who did not fight their corner will be doomed to extinction.

The time line here is key:

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/muckraker/sondland-trump-call-ukraine-military-aid

‘A key call between President Trump and a U.S. ambassador involved in the Ukraine pressure campaign was revealed Monday evening, just before the diplomat was blocked from speaking to Congress about the endeavor. Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, called President Trump last month after a career US official in Kyiv rang the alarm about Trump allegedly leveraging military aid for political favors from Ukraine. Sondland’s call to the President occurred within a roughly five-hour gap between a text from Bill Taylor, the charge d’affaires at the U.S. embassy, and Sondland’s text response, the New York Times and Wall Street Journal reported. Taylor had said that it “crazy” the aid was being withheld for “help with a political campaign.” When Sondland responded, he denied the allegation, claiming: “President has been crystal clear no quid pro quo’s of any kind.”Sondland then instructed Taylor to stop putting his concerns in writing and to call Secretary of State Pompeo or a Pompeo aide if he wanted to discuss the matter further.’

This should put the nail in the coffin for this Vampire in Chief. Oh wait – the discussion continues:

‘What exactly Trump said on his call to Sondland and whether the President was aware of the effort to contain the damage already done by his Ukraine-related conduct, are unanswered questions.’

Seriously? WTF do you think Trump was talking to Sondland about? His golf game?

How STUPID are these Trump sycophants? This captures it nicely!

https://talkingpointsmemo.com/news/matt-gaetz-kangaroo-court-captain-impeachment

Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL), elected representative and lawyer, is apparently under the impression that the expression “kangaroo court” is named after the mustachioed eponymous character of a ’50s children’s TV show, “Captain Kangaroo.”

I’ve been saying Trump supporters have IQs in the teens. It seems I have overestimated their intelligence!

Ali Velshi is not where one goes to intelligently discussion things like fiscal policy but he just had on some fiscal hawk woman who is supposed to be decent. She noted that at least someone is projecting a Federal deficit that will be just shy of $1 trillion. She then had this chart that noted without all of Trump’s fiscal insanity, the deficit might have been a mere $428 billion. OK I was working on something else and she was boring me so I did not mentally capture all of her chart.

Too bad as it would have at least been more intelligent that whatever is about to come out of Larry Kudlow’s mouth. Of course – MAGA!

With the trade balance rapidly deteriorating due to Trump’s trade wars (now at the worst level in a decade), why would we want to reduce the budget deficit?

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOPGSTB

Keynes correctly explained this decades ago:

“It is often pointed out that, when loan-expenditure was on a larger scale as a result of official encouragement, this did not prevent an increase of unemployment. But at that time it was offsetting incompletely an even more rapid deterioration in our foreign balance. The effects of an increase or decrease of £100,000,000 in our loan-expenditure are, broadly speaking, equal to the effects of an increase or decrease of £100,000,000 in our foreign balance. Formerly we had no visible benefit from our loan-expenditure, because it was being offset by a deterioration in our foreign balance. Recently we have had no visible benefit from the improvement in our foreign balance, because it has been offset by the reduction in our loan-expenditure. To-day for the first time it is open to us, if we choose, to have both factors favourable at once.

“If these conclusions cannot be refuted, is it not advisable to act upon them? The contrary policy of endeavouring to balance the Budget by impositions, restrictions, and precautions will surely fail, because it must have the effect of diminishing the national spending power, and hence the national income.”

The Means to Prosperity, p. 16

As Keynes points out, reducing the budget deficit (loan-expenditure) must fail because it will have the effect of reducing GDP. If the economy falls into recession, the budget deficit will have to be increased significantly to achieve growth again.

Can anyone tell me why President Bill Clinton was required to give a video deposition for putting a cigar in someone’s coochiebox but donald trump breaks every rule under the sun and was never asked to give legal testimony??

Because Mueller failed to do his job. He really blew the investigation and ended up with nothing. Hard to believe given all the obvious evidence.

mueller made a career as a stellar federal investigator. and to this day, i believe him to be fair and impartial. but mueller is 75 years old. he exhibits the same deficiency that biden and sanders have-they are all too old to hold critical positions. mueller from 15 years ago would have sank the president. the mueller of today, while respectable, is unable to complete the job. let this be a lesson to those who believe biden, sanders (and trump) are not too old to hold the most important office in the world. mueller failed to do his job simply because he became too old to do his job well. you see the results. i have seen many businesses flounder because workers were afraid to point out, the old man leading the show has lost his edge.

baffling,

You may be right, but I think more important is that he is an inveterate rule follower and obeyer of chains of command. So he ruled out indicting the president, and when he testified he agreed to all the limits imposed on him by Barr.

By others than Barr, but the point is valid. He stuck to a narrow mandate rather than point out the obvious.

Remember – a Democrat having an affair is a HIGH CRIME but a Republican committing treason is good leadership. MAGA!

the economy is already in recession. the ISM manufacturing is now at 47.1 ( which is contraction). the transportation is in recession because they do not have anything to carry. the agricultural sector is in recession ( no china sales). that is 20 % of the economy per Krugman. Also, my favorite indicator is the corporate press and some bloggers who try to explain away recession harbingers or signs of recession by stating …this time is different…

If my usual rule of thumb is correct, namely that the loudest denials that we are in a recession happen right as the economy tips into recession, then I would agree with you. The numbers say no, but the rule of thumb says yes. Is this time different? Probably not.

Dear Folks,

This isn’t going to be yet another attack on Trump but just a little more on what the original point of the post was – the likelihood of recession and whether we will know. Neil Ericsson gave a nice little talk about the ability of government agencies to forecast debt, and his main conclusion was that recessions and turning point were what messed up the forecasts the most. In short, the government agencies don’t have a good track record of getting them until after the fact. Tara was right there and could have disagreed but didn’t, rightly. I think she is right in her claims, but all of this has to be taken with a grain of salt.

Julian

Which is the whole point of the Shamelessly Unmathematical Willie Rule – when the consensus is that we are absolutely, positively not in a recession, we are already in a recession. When the consensus is that we are absolutely, positively, finally in a recession, we are on the way out of the recession. Last time was actually different, because the recession was deeper and lasted longer. I don’t expect this one to be as deep or as long. But, who knows. The sharp V isn’t likely, either, because this won’t be precipitated by interest rate hikes. It will be precipitated by tariffs and other policy blunders. Maybe the Syrian situation will be the final straw.

Parts of Europe probably are in recession already, which means the potential for the start of a recession there in 2020 is zero. It’s already started. This economy has me more confused than certain, so I’m sticking to mid-2020 for the fearless prediction of a downturn. That said, if it comes a whole lot sooner, it would not be all that surprising, based on the Shamelessly Unmathematical Willie Rule.