Today, we are pleased to present a guest contribution written by Jian Wang (Chinese University of Hong Kong – Shenzhen) and Jason Wu (Hong Kong Monetary Authority). All views are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of HKMA.

Following the 2008 global financial crisis, countercyclical capital flow management policy has been recommended, especially for emerging economies, as a way to defend against financial instability and to preserve monetary autonomy. Rey (2013) shows that over the global financial cycles, shocks emanating from “center economies” such as the U.S. induce large and volatile international capital flows and prevent the conduct of independent monetary policy for countries with open capital markets, even if they have flexible exchange rate arrangements. IMF (2011) argues that volatile capital flows may carry macroeconomic and financial stability risks to receiving countries, and measures to manage capital flows can help mitigate these risks. These arguments echoed early voices in the 1990s that capital control policies should be adopted in the countries for which currencies were still pegged to the U.S. dollar or whose domestic financial markets remained underdeveloped.

As a practical matter, however, it is not clear if countries follow this policy recommendation and if policies effectively shield an economy from volatile international capital inflows and outflows. For instance, Fernandez et al. (2015) find that capital controls in 78 countries are acyclical over the period 1995-2011. The empirical support for the effectiveness of capital flow management policy is also at best mixed.[1]

In a recent paper, we contribute to the literature by providing empirical evidence that emerging market economies (EMEs) tend to adopt countercyclical capital flow management in response to U.S. monetary shocks. Using these shocks as exogenous instruments, we further show that the actions to manage capital flows are indeed effective in altering portfolio flows, which help justify their use.

Two important deviations from the literature account for the differences between our results and previous empirical findings. First, we focus on the quarterly changes in the number of capital flow management policies for a group of EMEs, using the novel dataset of Pasricha et al. (2018). Whereas most previous studies focus on the presence of capital controls, as measured for example by an annual capital control index, changes in the number of capital flow management policies measure the time-varying intensity of capital flow management, and are therefore a good gauge of the cyclical dynamics of these policies.

Second, we use a very powerful and arguably exogenous “push” factor — U.S. monetary policy shocks — to explain the imposition of capital flow management policies and identify their effectiveness. Using these shocks as exogenous instruments helps us resolve a classic simultaneity problem: it is hard to identify the causal effect of capital controls on capital flows when countries with more volatile flows are also more likely to impose controls. Our instrumental variable approach overcomes this simultaneity by applying the key insight of works such as Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2019) and Rey (2013) that global factors, such as U.S. monetary policy shocks, bring about global financial cycles that lead to excessive surges and retrenchments in capital flows in “periphery” countries, which in turn necessitates the use of capital flow management. Indeed, we show empirically that EMEs take capital flow management actions in response to unanticipated U.S. monetary shocks in the prior quarter; in turn, capital flow management actions propagated by these shocks alter portfolio flows in the intended direction in the following quarter. This timeline in our empirical study is designed to eliminate any impact of monetary policy shocks on capital flows through channels other than the shocks’ effects on capital flows management.

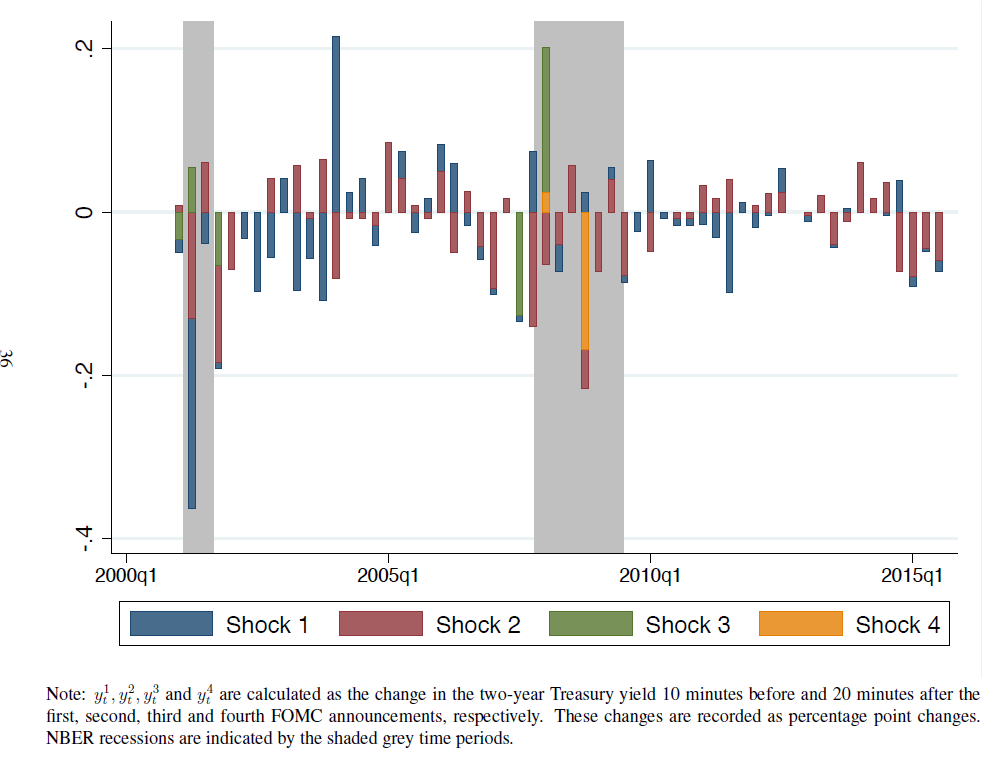

We measure U.S. monetary policy shocks as the changes to the two-year on-the-run Treasury yield over a short time window that surrounds FOMC announcements.[2] The figure below displays the monetary policy shocks in each quarter of our sample.

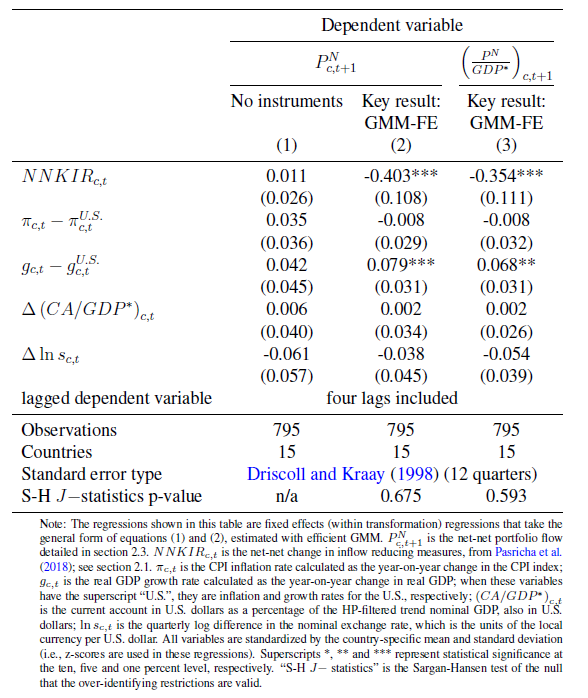

For a panel of 15 EMEs, we first regress the number of “net-net” capital flow management actions—notated as NNIKR—in quarter t on these shocks ( and ) in quarter t-1 and other pre-determined variables.[3] We show that for the average EME, a “dovish” (“hawkish”) U.S. monetary policy shock of one percentage point results in a 1.7 standard deviation increase (decline) in the “net-net” number of capital inflow reducing actions in the following quarter (see the table below).

We then include U.S. monetary policy shocks as instruments in a panel generalized method of moments (GMM) framework where the dependent variable measures portfolio flows into and out of the 15 EMEs in quarter t+1. The estimated causal effect in our baseline specification suggests that a one standard deviation increase in the “net-net” number of inflow reducing actions in quarter t, which is in response to a dovish U.S. monetary policy shock in quarter t-1, causes a two-fifths of a standard deviation decline in “net-net” portfolio inflows—notated as —in the next quarter t+1 (see the table below). This estimate is robust to various alternative specifications.

Delving into the drivers behind our results, we document a couple of interesting asymmetries. The first is that our key result is driven by the effectiveness of net inflow tightening actions applied on non-residents in altering net portfolio inflows from abroad, whereas we could not find evidence that net outflow easing actions applied on residents react to U.S. monetary policy shocks.[4] Focusing on the role of net inflow tightening actions applied on non-residents, a second asymmetry we find resonates with the “2.5-lemma” paradigm of Han and Wei (2018) — EMEs tend to take actions to stem inflows when the U.S. eases monetary policy and these actions are indeed effective in doing so, whereas there is no statistically significant evidence that actions are taken when the U.S. tightens monetary policy. This finding suggests that capital flow management policies may be preemptive: if the policy succeeds fending off the capital inflows driven by the easing policy in the U.S., EMEs that adopt the policy may face less pressure to stabilize their financial markets when the U.S. reverses its monetary policy. For instance, Ostry et al. (2012) find that during the global financial crisis, economies with stronger pre-crisis capital controls or foreign exchange-related prudential measures were in general more resilient.

It is important to clarify the issues that this paper does not address. Although we provide empirical evidence that capital flow management in EMEs react to U.S. monetary policy shocks and that the actions alter portfolio flows, our empirical results do not say anything about which types of capital controls are optimal under what circumstances, nor anything about the practical implementation challenges associated with using capital flows management—such as complexity, credibility, and coordination with other policies, as stipulated by Mendoza (2016) in the broader context of macroprudential policies. As well, our study does not assess the costs of capital controls, such as a loss in financial market efficiency and an increase in risks related to say shadow banking activities. Finally, our empirical framework does not directly test if the use of capital controls improves a country’s monetary policy autonomy, which is the subject of Han and Wei (2018) and Aizenman et al. (2017).

References

Aizenman, J., M. Chinn, and H. Ito, “Financial spillovers and macroprudential policies,” NBER Working Paper No. 24105, 2017.

Ben Zeev, N., “Capital controls as shock absorbers,” Journal of International Economics, 2017, 109, 43–67.

Chamon, M. and M. Garcia, “Capital controls in Brazil: Effective?,” Journal of International Money and Finance, 2016, 61, 163–187.

Edison, H. and C. Reinhart, “Stopping hot money,” Journal of Development Economics, 2001, 66, 533–553.

Fernandez, A., A. Rebucci, and M. Uribe, “Are capital controls countercyclical?,” Journal of Monetary Economics, 2015, 76, 1–14.

Forbes, K., M. Fratzscher, and R. Straub, “Capital-flow management measures: What are they good for?,” Journal of International Economics, 2015, 96, S76–S97.

Forbes, K., M. Fratzscher, T. Kostka, and R. Straub, “Bubble thy neighbour: Portfolio effects and externalities from capital controls,” Journal of International Economics, 2016, 99, 85–104.

Han, X. and S. Wei, “International transmission of monetary shocks: Between a trilemma and dilemma,” Journal of International Economics, 2018, 110, 205–219.

IMF, “Recent experiences in managing capital inflows: Cross-cutting themes and possible framework,” IMF Policy Paper, 2011.

Klein, M., “Capital controls: Gates versus walls,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2012, Fall, 317–355.

Mendoza, E., G., “Macroprudential policy: Promise and challenges,” NBER Working Paper No. 22868, 2016.

Miranda-Agrippino, S. and H. Rey, “US monetary policy and the global financial cycle,” NBER

Working Paper No. 21722, 2019.

Ostry, J. D., A. R. Ghosh, M. Chamon, and M. S. Qureshi, “Tools for managing financial stability risks from capital inflows,” Journal of International Economics, 2012, 88(2), 407–421.

Pasricha, G. K., M. Falagiarda, M. Bijsterbosch, and J. Aizenman, “Domestic and multilateral effects of capital controls in emerging markets,” Journal of International Economics, 2018, 115, 48–58.

Rey, H., “Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence,” Jackson Hole Symposium on Economic Policy, 2013, pp. 284–333.

Endnotes

[1] For instance, Edison and Reinhart (2001) find that capital controls failed to stop hot money in two out of three emerging markets during the crises of the 1990s. More recently, Forbes et al. (2015) find that most capital control measures do not significantly affect capital flows and other key targets in an expansive but short panel of countries. Other recent examples of negative or mixed findings include Klein (2012), Forbes et al. (2016) and Chamon and Garcia (2016). In contrast, Ostry et al. (2012) and Ben Zeev (2017) document empirical evidence in favor of capital flow management policies, especially for emerging markets.

[2] In a robustness check, we also include the shocks extracted from 10-year Treasury yields to capture monetary policy shocks to long-term interest rates.

[3] This measure is “net-net” as it firsts nets tightening and easing measures separately for inflows and outflows, and then nets across net inflow measures and net outflow measures. See Parischa et al. (2018) for a more precise definition.

[4] In a related study, Ben Zeev (2017) finds that capital inflow controls help to stabilize a country’s output—rather than capital flows—in response to global credit supply shocks, while no such evidence exists for capital outflow controls.

This post written by Jian Wang and Jason Wu.

This comment is directed more at the leaders of China, than at the authors of this solid paper which does a good job of extrapolating some of the effects of U.S. monetary policy on EMEs (some of it obviously negative) and if some of the capital controls on country flows are effective and/or constructive. SOME of the capital controls are no doubt beneficial.

I’m very curious why Chinese government leaders are so hysterically horrified and have a phobic fear of foreign capital flows and foreign ownership in their country (of say a residential dwelling/apartment for example, is an example that comes to mind off-hand). I understand the history, but frankly it is my opinion Chinese citizens are largely brainwashed into thinking they should have an indefinite and everlasting fear of foreign influence (outside of replicating good ideas and stamping a local brand name on it, of which they seem to have zero problem with that part of “foreign influence”). Chinese government leadership is now worried their growth rate is slowing, to a point that could cause problems with their economic policy nursemaid soothing of all their other government abuses (credit scores based on a person’s docility and swiftness to get on their knees, facial recognition, activities in Xinjiang, which most Han couldn’t possibly care less about, but still an abuse).

Anyway, my point is, if Chinese want faster growth, nothing could speed that up quicker than foreign capital inflows (i.e. investment, which “Oh My God!!!! It’s Satan in our midst!!!!! Get the chemical fumigator for the foreign vermin Ting Ting!!!!” implies foreign equity ownership. Oh wow, I said it out loud and have not dropped dead yet…… Amazing…….. But then that would get in the way of the cultural mindset of eternal and everlasting fear of foreign influence. Something about “Open the windows and you let flies and mosquitos into your home”?? Uuuuuuhh, gee, do you think you guys have “survived” all those flies you let in after around 1979?? Or did they like it more with “zero house flies” and people starving to death and teachers being thrown off balconies??? Was that a more “enjoyable lifestyle”. I know some Chinese rural people still think so….. but…… I think I would go with more house flies if I were them. But if wealthy/affluent Chinese (many of them high-placed government leaders) want to keep sneaking their assets into US dollars, U.S. government debt instruments, and U.S. commercial real estate through porous capital controls— HEY, I’m cool with it.

I think study is well done and looks reasonable.

I do not disagree with you, Moses, that probably the Chinese policy is unreasonably paranoid, especially given the size of their economy, with the sorts of controls this study looks at probably more important for smaller emerging market nations. But that paranoia in China is deeply seated and reflects ongoing nationalism and emphasis on such historical episodes as the Opium Wars, which they do make a lot of noise about to their population.