From the National Corn Growers Association:

U.S. soybeans and corn are prime targets for tariffs. As the top two export commodities for our country, together they account for about one-fourth of total U.S. agricultural export value. As such, a repeated tariff-based approach to addressing trade with China places a target on both U.S. soybeans and corn. Farmers and rural economies pay the price as a result.

The report’s main conclusion (read the whole study for assumptions, model, etc.):

Study Findings

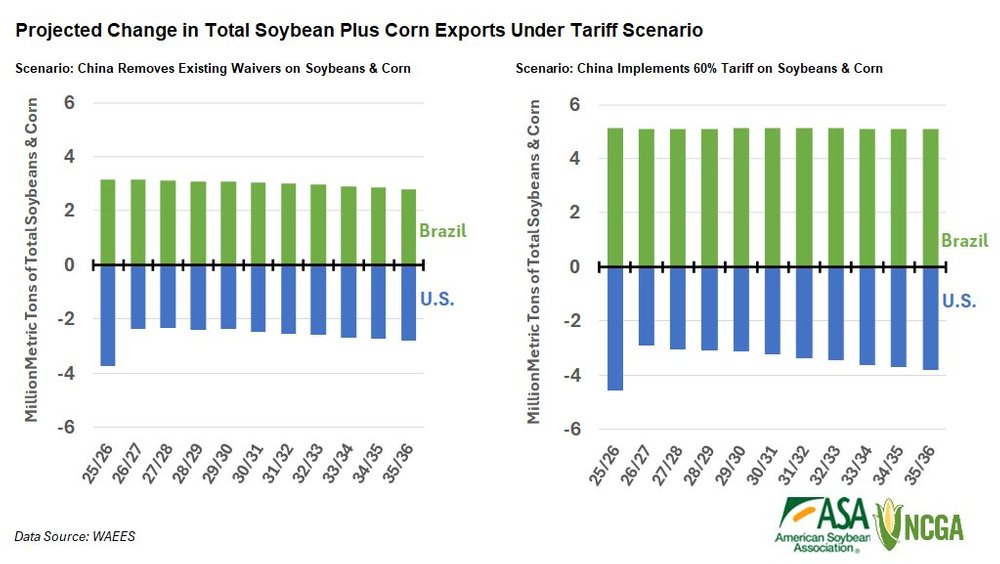

U.S. Soybean & Corn Exports Drop While Brazil Gains Market Share

If China cancels its waiver and reverts to tariffs already on the books, U.S. soybean exports to China fall between 14 and 16 million metric tons annually, an average decline of 51.8% from baseline levels expected for those years. U.S. corn exports to China fall about 2.2 million metric tons annually, an average decline of 84.3% from the baseline expectation. Although the export quantity decline is much lower for corn than soybeans, reflecting the smaller quantity of corn exported to China, the relative change from the baseline quantity is significant for corn.

While it’s possible to divert exports to other nations, there is not enough demand from the rest of the world to offset the major loss of soybean exports to China. At the same time, Brazil and Argentina gain global market share with increased exports. The U.S. loses a combined total of 2.3 to 3.7 million metric tons of soybean plus corn exports annually, while Brazil gains an average of 4.6 million metric tons of soybean plus corn exports annually.

Chinese tariffs on soybeans and corn from the U.S. but not Brazil provide incentive for Brazilian farmers to expand production area even more rapidly than baseline growth. The expansion is magnified because some land area in Brazil can be used to grow a soybean and corn crop in the same year. Land transitioned into production area in Brazil will remain in production. The impact on U.S. soybean and corn farmers isn’t limited to a short-term price shock: This is a long-lasting ramification that changes the global supply structure.

A 60% retaliatory tariff level intensifies the shock, resulting in a loss of over 25 million metric tons of soybean exports to China and nearly 90% of corn exports to China. In this situation, the U.S. loses a combined total of 2.9 to 4.6 million metric tons of soybean plus corn exports annually, while Brazil gains an average of 8.9 million metric tons of annual soybean plus corn exports over the projection timeline.

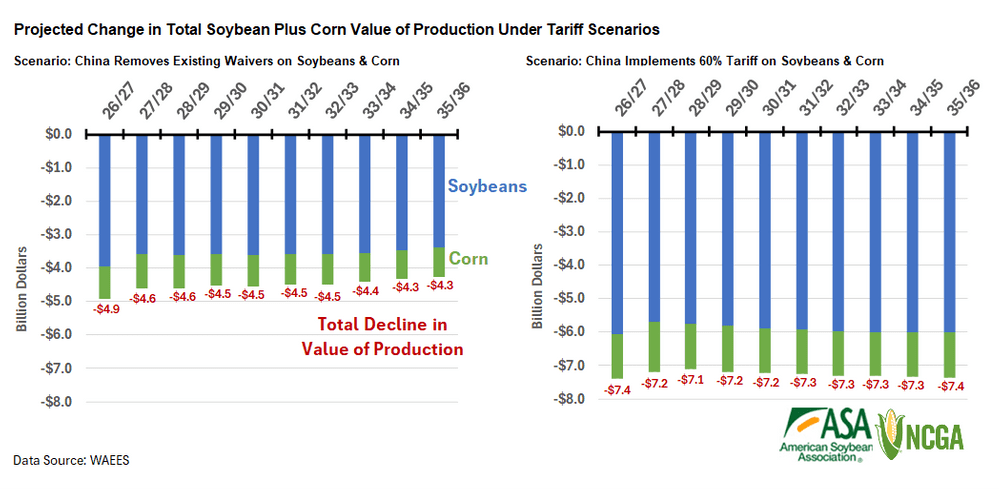

Here’s their assessment of the impact on US production in both scenarios.

In sum, farmers will see cash income decline while costs increase.

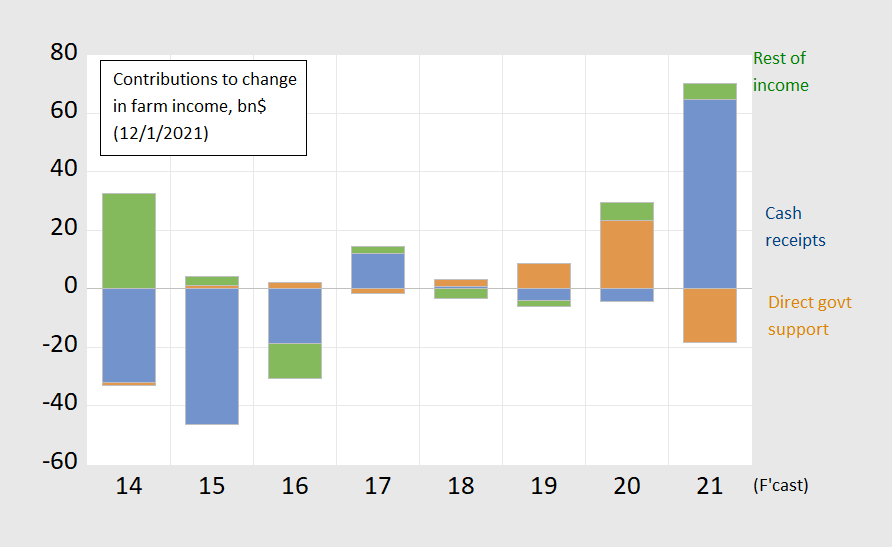

From a January 2022 post, one can see how massive a transfer the Trump administration had to implement in order to prop up farm income in the wake of that trade war, and how cash income popped up in 2021. Hence, despite lower government support, net income is forecasted to be up.

Figure 1: Contributions to change in farm income from cash receipts from sales (blue bar), from direct government support (brown bar), and from all other components (green bar). Source: USDA, data of 12/1/2021.

This time around, if Trump were to impose 10-20% tariffs on everything imported and 60% tariffs on Chinese imports, then there’ll be a lot more people in line for bailouts than last time. If you believe the farmers will be first in line next round, then there’s a bridge I want to sell you.

See more on the impact on the Midwest here.

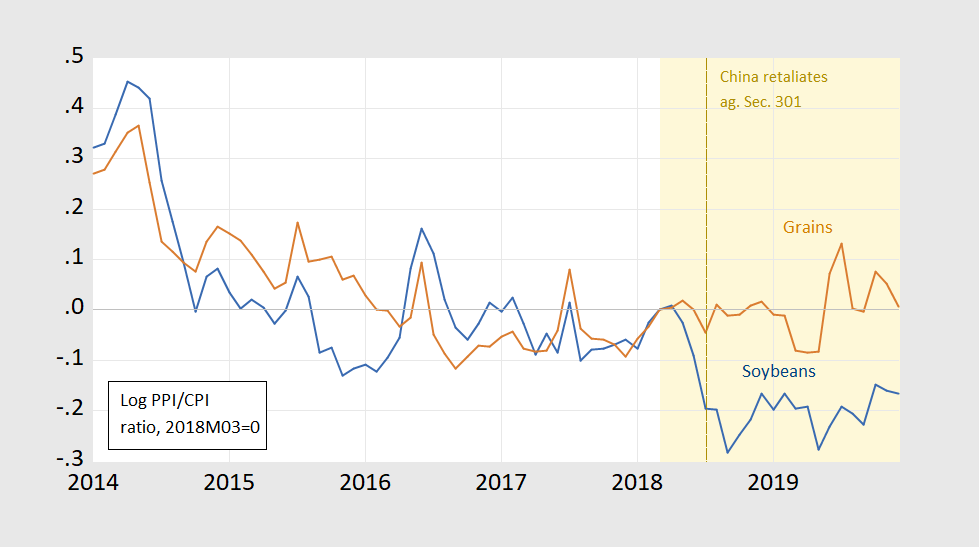

For a nostalgic trip down event-study lane, see this January 2020 post, with this graph:

Figure 2: CPI deflated PPI for soybeans (blue) and grains (brown), in logs 2018M03=0. Orange shading denotes period during which China Section 301 action is announced/implemented. Brown dashed line is when Chinese tariffs on US soybeans goes into effect. Source: BLS via FRED, author’s calculations.

I am surprised that this did not feature in the whole political dialogue sooner. Trump tariffs would surely lead to retaliatory tariffs against us, with US agricultural producers a likely target.

Steven Kopits: Should’ve been. I mentioned this issue in this post (October 27).

I meant the Harris campaign. Most of what I saw regarded inflationary pressures on consumers due to tariffs. Normally, though, we’d typically discuss retaliatory tariffs. Given the importance of agriculture in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, to name just two swing states, I would have thought greater emphasis would have been placed on the negative effects on US farmers. But maybe I missed it.

As for Oct. 27, pgl, that’s pretty late in the game for a Nov. 5 election.

You did not read the October 27 post?

The cost of Trump tariffs will be born by US consumers – as it was last time.

https://www.cnn.com/2024/11/04/business/tariffs-donald-trump-prices/index.html

“At the same time, Brazil and Argentina gain global market share with increased exports.”

This is a race between weather and acreage expansion. So far, expansion is winning.

“…incentive for Brazilian farmers to expand production area even more rapidly than baseline growth.”

Read: “accelerated rainforest destruction “.

Let’s not ignore the possibility that Trump will “discover” improved Chinese trade behavior after a very targeted round of contracts and licensing agreements are signed, and announce that tariffs are no longer necessary.

This is funny. Elon Musk, one of the biggest grifters in history, has his latest grift exposed in court. His lawyer admitted to the judge that Musk’s million dollar random lottery to entice people to register to vote and sign a petition is all fake. It isn’t random at all. The “winners” are pre-selected and vetted to serve as good spokespeople for the campaign and required to sign a performance contract to get the money. In fact, Musk’s lawyer conceded, there is no prize to be won and the last two “winners” before the election have already been selected and signed contracts.

The grift never ends with these guys.

Off topic – spill-over from U.S. policy and U.S. performance:

U.S. monetary policy is notoriously influential outside the U.S. High Fed rates weaken investment, raise debt service costs and increase import bills abroad, weakening global growth.

A big “this time is different” story in the latest U.S. rate cycle is that the U.S. has grown strongly despite contractionary monetary conditions. Turns out “this time is different” may extend beyond U.S. borders. Ruchir Sharma (FT, Rockefeller Capital) says that the largest developing economies are also doing quite well:

https://www.ft.com/content/b7ad1107-07c2-4b40-b26d-35509938d2bd

Sharma focuses on conditions and on economic management among large developing economies to explain their resilience to the Fed rate shock. He doesn’t have much to say about the real-side effects of U.S. resilience on developing economies, but I suspect thse effects are also worth a look. Recession in the U.S. typically results in a sharp drop in real imports. There was a drop in 2023, but it was smaller than any recession-sized drop:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IMPGSC1#0

Sharma may have his own reasons for ignoring the real effects of U.S. growth on developing economies; a favorite theme of his is that U.S. growth is a mirage, all the result of the better offs getting better off. That claim is open to debate, but when you measure benefits to the rest of the world through U.S. real exports, the case is pretty clear.

I also find Sharma’s point interesting in light of China’s relative weakness. Large developing countries are weathering a Fed rate shock and Chinese weakness, un part because of their own economic management, but probably also because of U.S. strength.

Enough with the quibbles. Sharma makes an interesting “this time is different” claim. Worth a look.

As of today, the threat is up to 100% tariffs on all imports from Mexico:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2024/11/04/trump-mexico-tariff-trade/

In 2023, Mexico supplanted China as the top exporter to the U.S. So figure a substantially larger impact on the U.S. economy than predicted in previous studies.

So far the “close borders and throw out all (brown) illegals” xenophobic wet dream has been presumed possible without hyperinflation – by a model where the dirty jobs in meat agriculture would simply be moved south of the border (together with the workers). Sure a lot of US rural Ag factories would close for a lack of workers, but they would just reopen in Mexico. So except for caravans of chicken, pigs and cows heading south to be slaughtered – then meat heading north to be eaten – the increases in meat prices would be manageable. However, if you combine the deportation of most Ag workers with a 100% tax on trade (in one or both directions) with Mexico, then we would see shortages and extreme increases in food prices.

What always gets me is that the Continuing Appropriations for the Farm Bill gets passed year after year regardless of D or R White House. D or R House, D or R Senate – although Republicans always want to cut farm subsidizes – indeed Trump’s Project 2025 would cut Farm Bill drastically https://investigatemidwest.org/2024/07/19/farm-programs-usda-would-shrink-under-project-2025-goals-for-ag/