This probably seems like a silly question, but it’s actually a hard one to answer quantitatively.

The standard measure is the CPI deflated trade weighted exchange rate, but this uses prices relevant to consumers, not producers. And not cost of production. As discussed in Chinn (2006), unit labor costs (ULC) would be the most appropriate. Unfortunately, neither OECD nor IMF report a ULC deflated exchange rate for China.

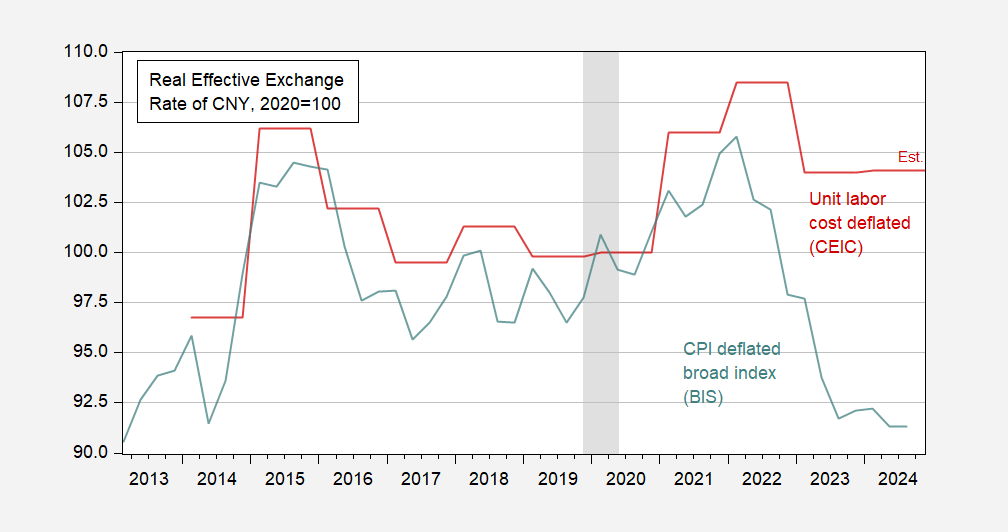

Here’s CEIC’s estimate compared against the BIS CPI deflated rate.

Figure 1: CPI deflated value of Chinese yuan (blue), ULC deflated value of Chinese yuan (red), both 2020=100. Source: BIS via FRED, CEIC.

Note that the ULC deflated series for China is for the entire economy, not the tradables sector, which would be the appropriate one for determining competitiveness. For more discussion of macro competitiveness, see Chinn and Johnston (1996).

The question seems to be about an attempt to fund an aggregate measure of what is, in reality, a bunch if individual competitions. Every product has its own price in its own market. No wonder competitiveness is hard to quantify; it’s an abstraction.

Off topic – the Fed’s funds rate target from tue Summary of Economic Projections:

The Board collectively expects the funds rate to end 2025 at 3.9%, up from 3.4% in the September SEP. For end-2026, it’s 3.4% vs 2.9%. That’s half a percentage point higher for both years. Nearly all the rise in the 2025 estimate is accounted for by a higher inflation estimate, 2.4% now vs 2.1% in September. The extra 0.1% is accounted for by a higher estimate of the neutral rate.

The long-term expected funds rate is now 3.0% vs 2.9% in September and 2.5% a year or so ago. So the Board now collectively thinks the neutral funds rate is 1.0%, rather than the 0.5% that was the central expectation for quite some time.

Also , assuming the Fed hasn’t already induced a recession, the jobless rate forecasts in the SEP imply that no recession is expected in the forecast period.

Off topic – Korean markets:

South Korea’s won has hit its weakest price vs the dollar since 2009. Korea’s political troubles are a big driver of won weakness, but so is dollar strength. Here’s Krw/Usd

https://tradingeconomics.com/south-korea/currency

Government officials have been warning of market intervention to stabilize the won for the past week or so. I can find no reports indicating intervention, but today’s won bounce is suggestive.