Today, we’re pleased to present a guest contribution by Laurent Ferrara (Professor of Economics at Skema Business School, Paris and Chair of the French Business Cycle Dating Committee), and Jamel Saadaoui (Professor at University of Paris 8 – LED).

After years of rising inflation in the wake of the post-Covid recovery and the war in Ukraine, disinflationary pressures are now visible across all advanced economies. In some countries, inflation has even fallen well below central bank targets. This is the case for France, where the latest figures indicate that consumer prices rose by only 0.9% year-on-year in November 2025 (source : INSEE). Forecasts also point to persistently low inflation over the next two years—1.3% in 2026 and 1.8% in 2027, following 1% in 2025—according to the latest Banque de France forecasts.

When assessing the balance of risks surrounding this baseline scenario, geopolitical risks must be taken seriously, given the current climate of global tensions, particularly in Europe. Recent academic literature has begun to document the dynamic effects of geopolitical tensions on inflation, although their sign is theoretically ambiguous. On the one hand, weaker demand -through lower economic growth and declining consumer sentiment – tends to depress consumer prices. On the other hand, geopolitical shocks raise commodity prices and trigger currency depreciation, both of which push inflation upward. Oil prices, in particular, respond to fears of supply disruptions (see Mignon and Saadaoui) .

Beyond imported inflation, fiscal dynamics are also likely to reinforce inflationary pressures. Rising defense spending, increasing public debt, and tighter financial conditions combine to exacerbate fiscal imbalances and financial stress, likely adding to the overall inflationary environment.

Caldara et al. have recently proposed to estimate the effects of the Geopolitical Risk index (GPR index developed by Caldara and Iacovello) on inflation around the globe. Using a monthly global SVAR spanning several decades, they show that heightened geopolitical tensions systematically increase commodity prices. They also demonstrate that this “commodity channel” contributes to higher inflation despite simultaneous deflationary forces stemming from weaker output, lower consumer sentiment, reduced trade, and tighter financial conditions. We partly review this literature in a recent work that we did, forthcoming in the Revue d’Economie Financière (see slides here).

What do we obtain when estimating the effects of a geopolitical shock on French inflation? Beyond the well-known GPR index, several alternative geopolitical indicators have recently been developed in the research literature. A particularly interesting contribution is provided by Bondarenko et al., who focus on European countries. Noting that the GPR index relies primarily on U.S.-centric newspapers, they propose a text-mining approach based on local newspapers from five major euro area economies—Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the Netherlands—to construct country-specific measures of geopolitical risk.

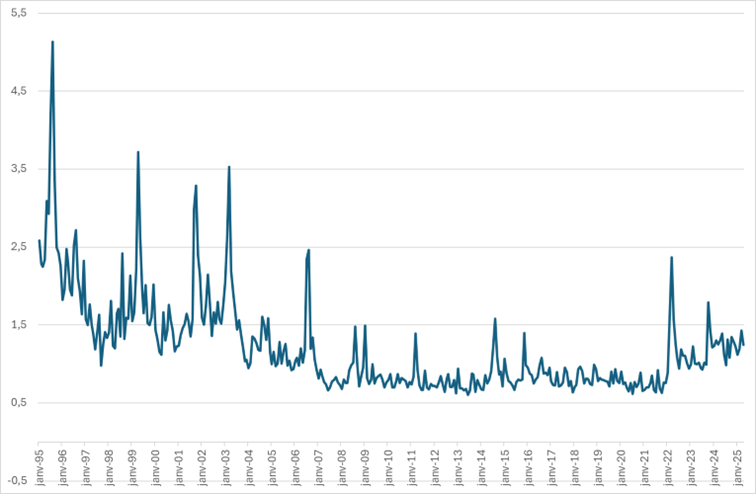

Let’s base our empirical analysis on the index of Bondarenko for France (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Geopolitical risk for France, monthly data from Jan. 1995 to April 2025 (Bondarenko et al.) Source: https://github.com/YvesSchueler/GeopoliticalRiskPerceptions

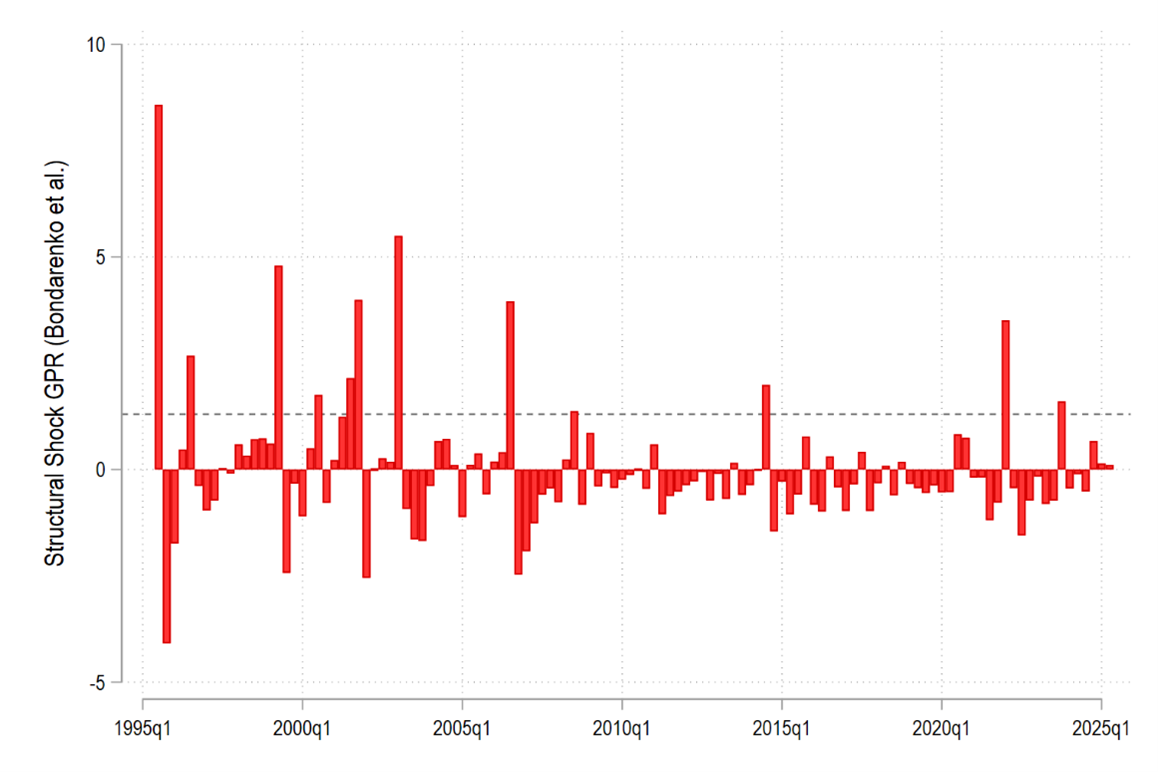

We are going to estimate a structural geopolitical shock and to look at its dynamic effect on inflation using a Local Projection approach. The structural geopolitical shock is recovered using a Choleski identification in SVAR model, that also controls for GDP growth and changes in oil prices (Brent). We estimate the model at the quarterly frequency. The structural geopolitical shock stemming from this approach is presented Figure 2.

Figure 2: Estimated structural geopolitical shock using Choleski identification in a SVAR model

Source: authors’ computations

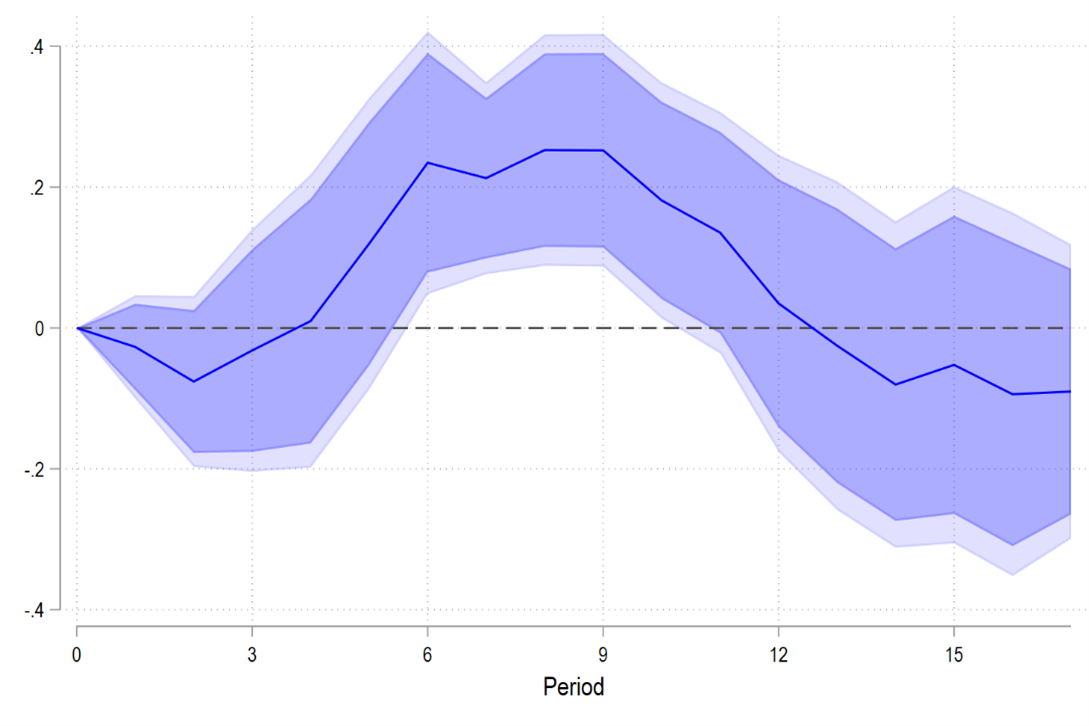

Based on this estimated geopolitical shock, IRFs can be computed using the Local Projection methodology. The IRF of inflation to a one standard-deviation shock (about 1.5) is presented in Figure 3. The maximum impact of about 0.25pp is reached after 2 years (8 quarters). Interestingly, there are no clear significant effects during the first year after the shock. A possible explanation is that negative demand effects are counter-balanced by increasing imported inflation.

Figure 3: IRF of inflation to a 1sd geopolitical shock for France

Source: authors’ computations

In policy terms, the future evolution of consumer prices will depend on the amplitude of a possible structural shock estimated by the geopolitical index from Bondarenko et al. Let’s assume that the amplitude is as large as the one observed during the war in Iraq, that is a value of 5.5 in 2003q1 (see Figure 2), representing about 3.7 times the standard deviation of the shock. Such a geopolitical event would likely generate a surplus of inflation of about 3.7*0.25=0.93pp after 8 quarters. If we translate the quarterly profile into annual figures, this would shift upward inflation in 2027 to about 2.5%, adding thus inflationary pressures to the baseline scenario for France (1.8% in 2027 according to Banque de France).

This post written by Laurent Ferrara and Jamel Saadaoui.

France’s inflation rate is substantially lower than that of the U.S. right now. Same thing for the EU:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1OvvA

There have been wider divergences in the past, both directions. What’s notable now is that U.S. inflation began to diverge upward from European inflation from April – Liberation Day.

Professor Farrara points out uncertainty as a cause of inflation. Here are similar measures of economic policy uncertainty for Europe and the U.S., indexed to January of this year:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=1OvyR

The greater uncertainty for the U.S. may help explain the upward divergence in the U.S. inflation rate, as would the greater increase in tariffs for the U.S.