Riding the dollar’s decline.

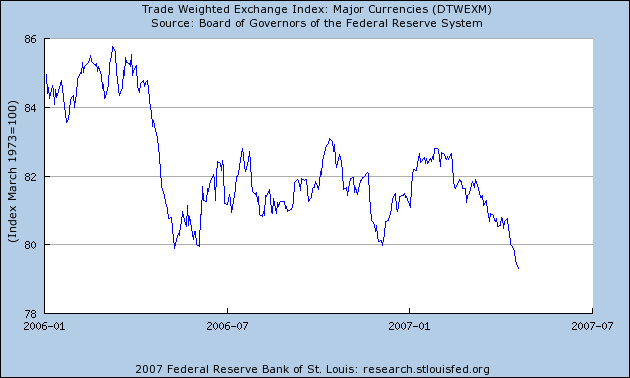

Figure 1: Trade weighted dollar value against major currencies. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II.

Is this a short term phenomenon, related to the configuration of policy rates in the US and the euro area? Or is it a more durable phenomenon? DeutscheBank thinks the latter.

“The growth rotation is partly cyclical but it is

also structural

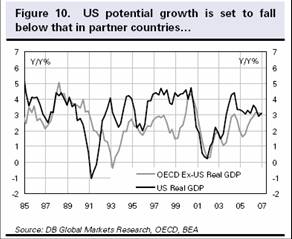

It is important to note that the growth rotation away from the US is not only cyclical but also structural in our view. Since the recovery from the early 1990s recession until recently, US GDP growth has generally been significantly higher than in the other expect that the US will grow faster than the Euro area and Japan, the differential is expected to be significantly smaller than it has been — about half. In the 1990s, while potential or trend growth in the US was widely estimated at about 3 1/2%, we now see trend growth of about 2 3/4%. With regard to Europe and Japan, potential or trend growth numbers had been successively revised down in recent years. They are now gradually drifting up and are probably no less than 2% going forward. So at a minimum, the differential has shrunk from 1.5% to 3/4%. In our view, the bad news on potential growth from population aging in the euro area and Japan was probably excessively priced into financial markets, while in the US it is likely that the slowing in potential growth has not been priced in yet.” Exchange Rate Perspectives, Deutsche Bank, April 20, 2007, pp. 6-7.

This phenomenon of growth rotation is illustrated in Figure 10 from DB. US growth is converging toward OECD ex.-US growth.

Figure 10 from Exchange Rate Perspectives, Deutsche Bank, April 20,2007.

I think this observation regarding long term growth — if it proves accurate — is of interest for two reasons.

- First, and most narrowly, this means that we may be in for a long period of secular weakness in the dollar, when this effect is added into the effect from reserve diversification away from dollar assets. In other words, the good times are over. Continued dollar decline worsens the term at which we exchange bundles of U.S. goods for foreign goods. Depreciation may stabilize the net international investment position of the U.S. so that our debt-to-GDP ratio fails to deteriorate even as we run current account deficits, but it does mean a reduction in our purchasing power of foreign-produced goods over time.

- Second, more broadly, this means the Administration’s forecast on growth and hence tax revenues may take a hit. The Troika forecast from last November had real GDP growing at 3% q4/q4 per year from 2008 to 2012. For some of us, this can be interpreted as the natural outcome of a (private and public) consumption boom. The relatively weak investment in business fixed investment since the end of the last recession has meant limited capital deepening. That in turn placed a drag on maintaining the productivity boom.

Of course, I may turn out to be wrong on this second point. Another new invention may come along to renew productivity acceleration. Or another China (or PBoC) — willing to pump up demand for dollar denominated assets — may enter global financial markets. But this hope merely highlights where macro policy of the last few years has placed us: at the mercy of the fates.

Technorati Tags: dollar, macroeconomic policy,

growth rotation,

productivity growth,

capital deepening,

reserve diversification,

exchange rates

Professor Chinn, I have a question about U.S. productivity growth. Here in America (unlike in Europe) productivity is amount of output per hour worked. However, the growth of information technology has enabled many workers to work outside of official workplace hours, e.g. a worker can use a laptop while on the train or while at home which means that more work is being done but it is being done outside of official workplace hours. Doesn’t this imply that productivity gains have been exaggerated and if so then by how much? Would it make sense to re-calculate U.S. productivity as output per worker to see how much of a discrepancy there might be?

A “Federal Reserve Note” is not a U.S.A. dollar. In 1973, Public Law 93-110 defined the U.S.A. dollar as consisting of 1/42.2222 fine troy ounces of gold.

Whoa, aren’t those Deutsche Bank people the same folks behind “Bretton Woods II–Deficits Don’t Matter” theory? Talk about conveniently changing their tune…

In any event, I am doubtful that any other country needs to supplant China as the Treasury buying suckers–I mean, clients at this point in time. There is no sign of a slowdown in PBoC Treasury buying, so Vietnam’s (or someone else’s) time hasn’t come to shake it in the Bretton Woods II conga line.

Another new invention may come along to renew productivity acceleration.

By productivity growth is decelerating! Ruh-roh…

“A New Era for the Dollar?”

Econbrowser commenting on whether dollar weakness reflects the closing of a “GDP Gap” v Japan and Europe.

…

I’m always confused about why people relate GDP growth to expected currency movements. Shouldn’t capital chase TFP growth (the marginal product of capital from the neoclassical growth model with population growth = rate of time discount + intertemporal elasticity of substitution times TFP growth rate) or at least the growth rate of labor productivity. I simply do not understand what growth in the labor force has to do with currency values. Is it that population growth rates change slowly? If so, shouldn’t we still net out differences in population growth rates? Menzie, can you help me here? Thanks.

Yes, there is always that huge emerging market of consumers in India and China that are just waiting for the right moment to unleash their consumer dreams (Isn’t there a Chinese delegation coming over for a shopping expedition soon?)[no amount of tariffs can dissuade these officials…]

I see in an auto piece that Toyota may have over-taken GM as the biggest car manufacturer this past quarter, but also that GM’s China plants were the only GM ones that made a profit. So it might be that more American industry, possibly the entire company, will move to the consumers…rather than trying to compete against an economy that has growth rates of 10%, year after year.

Charlie Stromeyer: I agree that it’s best to measure labor productivity in comparable terms. So, what would be best is to compare output per hour in nonfarm business sector in one country against another. Even better would be to use multifactor productivity (which is what theory predicts is important) across countries in different sectors.

jfund: It depends on the model one uses. Purchasing power parity held for aggregate price indices, then you’re right that productivity shouldn’t matter for the exchange rate. When there are nontradables, and PPP holds for tradables, then one has a Balassa-Samuelson model where inter-country intersectoral productivity differential growth rates matter. When all goods are tradable, but there is home bias in consumption, then one can get different effects from productivity growth. I think the authors of the DB piece were thinking of a model related to Balassa-Samuelson model, while allowing for deviations from PPP in tradables, and home bias in consumption.

Emmanuel: Well, organizations are not monolithic — so different parts of the organization have different views.

Aaron Krowne: Yes, I agree — productivity growth seems to be decelerating, and the question is whether it is mostly a cyclical factor (late in the business cycle) or more secular in nature. Too early to be sure, in my opinion.

This is all well and good, but why hasn’t the dollar depreciated much to the yen? The analysis makes sense to me with repsect to the Euro, but not the yen.

The danger with a depreciating currency is that inflation increases as imports and commodities increase in price, which means that short term interest rates will need to stay high.

calmo, It seems to me what matters is the marginal product of capital, which should rise (for any given capital stock) if the quantity of labor rises. So I think labor force growth does matter. Slower labor force growth reduces the marginal product of capital, thus causing capital to flow abroad (relatively speaking) and the domestic currency to depreciate.

MC: There is a problem with the font on this post. Apparently it is continuing to use the font from the figure caption instead of returning to normal. Some kind of tag probably needs to be inserted after the figure caption. (I tried inserting a closing font tag at the top of this comment to see what would happen.)

Sorry, Menzie. I must not have been clear. I don’t have any problem with using productivity growth of some variant for the reasons you suggest. But DB and many others continually push GDP growth. This is what I do not understand. Perhaps GDP growth is correlated with TFP growth and available more quickly because we don’t have to wait (more than a year) for the capital stock numbers from BEA. Even then labor productivity seems like a better bet.

jfund: Apologies for missing your point. Real GDP matters in monetary models because it’s a determinant of money demand. Productivity matters in certain models with nontradables because it affects relative prices (of tradables against nontradables, or home tradables against foreign tradables if PPP does not hold for tradables). In principle, both the size effect and differential productivity can then matter. DB — and many others — are not specific because the relative importance of each channel is uncertain.

On the point of timeliness vs. appropriateness, I agree that TFP loses out to labor productivity on the timeliness/frequency issue, while it wins on appropriateness. That’s why I’ve got papers using both measures. See

“The Usual Suspects? Productivity and Demand Shocks and Asia-Pacific Real Exchange Rates,” Review of International Economics 8(1) (February 2000). [pdf], and “Real Exchange Rate Levels, Productivity and Demand Shocks: Evidence from a Panel of 14 Countries,” w/L. Johnston, IMF working paper 97/66 [pdf].

buzzcut: I agree productivity differential effects can often be obscured by other effects (including short term factors like carry trade, distortions in the banking sector). Exchange rate pass through into domestic prices is something to think about, but typically this is thought to be a small number (even if pass through into import prices can be relatively large).

knzn: Sorry about that — it’s fixed now.

Exchange rate pass through into domestic prices is something to think about, but typically this is thought to be a small number (even if pass through into import prices can be relatively large).

Could this view be outdated? More and more manufactures are imported. The run up in gas prices is partly a reflection of the falling value of the dollar. What about other commodities?

Concievably, if the Chinese are getting squeezed on their export prices to the US due to their currency increasing in value relative to the dollar, they’re going to be less able (or interested) in reinvesting their trade dollars in T-bills. Not to mention that their ROI on US investments falls as the dollar falls.

buzzcut: I agree that he correlation between exchange rate changes and domestic price changes might be high right now, but that’s not prima facie evidence that the exchange rate changes cause the price inflation; rather it could be that both variables are being perturbed by a common shock (say monetary policy). In other words, a proper assessment of the extent of exchange rate pass through into the general price deflator would require some sort of instrumental variables regression approach.

calmo, here’s an article about how Beijing is concerned that Chinese consumers won’t spend:

http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/07_18/b4032044.htm

Professor Chinn, theory might predict that multifactor productivity is important but it appears that MFP is not that important in the real world. The paper “Intangible Capital and Economic Growth” shows that capital deepening is the primary driver of growth in labor productivity and that this supplants MFP as the main source of growth:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=943769

Anyways, I was not talking about MFP nor trying to compare productivity across countries, but instead gave a simple reason why it is fundamentally flawed to think of productivity as output per hour. Instead productivity should be output per worker (including, for example, even those workers at home who make a living trading goods on Ebay).

I agree that he correlation between exchange rate changes and domestic price changes might be high right now, but that’s not prima facie evidence that the exchange rate changes cause the price inflation; rather it could be that both variables are being perturbed by a common shock (say monetary policy). In other words, a proper assessment of the extent of exchange rate pass through into the general price deflator would require some sort of instrumental variables regression approach.

These issues are so highly cross corelated that even highly sophisticated multiple regression analysis probably can’t separate the various factors.

For example, you talk about monetary policy’s influence on inflation AND the exchange rate. That’s a tough nut to crack.

Another thing, even putting aside that the yuan is pegged to the dollar (and thus, dollar inflation should become yuan inflation), the Chinese economy is much more dependent on commodity prices than the US economy is, because Chinese industries are much more energy intensive (some would say wasteful). So commodity price increases due to a falling US dollar should cause Chinese good prices to increase at a higher rate than, say, goods from more efficient US or especially European manufacturers.

And those European manufacturers can use their higher Euro to invest in technology from the US at a lower price, thus allowing them to increase their productivity faster.

Buzzcut,

You are talking totally different condition when you talk of the yuan, yen, euro, and dollar. The economies of each currency area are different, the tax and regulatory structures are different, and the monetary policies are different.

Of the four the euro has actually been the most stable with the yuan, yen and dollar showing significant linkage.

We also see China releasing pent up production capacity so we should expect to see significant growth while both Japan and the US are moving more toward command economies and so growth rates would be moderate to declining.

The monetary conditions in Euroland are more stable but their socialist command economies waste resources and create unemployment.

But whether the decline in the dollar is a short term or long term phenomenon is actually dependent on the FED monetary policy. Right now the bias appears to be toward inflation, a declining dollar.

Charlie Stromeyer: Sorry for missing that issue. I think I can conceive of reasons why one would want to measure output per hour rather than worker, especially since time at work varies per worker, especially when taking into account part-time workers. What I think your point really suggests is that one should try to better measure the number of hours worked, by including time outside of offices, for instance.

Regarding intangibles and productivity measures, if you refer to the working paper you cited[pdf], you’ll note that the acceleration in MFP growth using conventional measures is 0.94, while allowing for intangibles still leads to an acceleration of 0.67. Hence, I think MFP is still an important factor.

buzzcut: I agree that dealing with endogeneity is hard. For an example of an attempt (which I think is successful), see David C Parsley, Helen A Popper, 1998, “Exchange rates, domestic prices, and central bank actions,” Southern Economic Journal 64 (4), available via JSTOR and PRoQuest.

Professor Chinn, I agree with you that MFP is still an important factor but capital deepening is the main driver of growth. This is a concern because of what you said in your post above:

“The relatively weak investment in business fixed investment since the end of the last recession has meant limited capital deepening. That in turn placed a drag on maintaining the productivity boom.”

The U.S. had winners and losers when the currency was valued higher; it will have winners and losers as the currency’s relative value declines.

Consumers will, undoubtedly be feeling more of a pinch, but domestic manufacturers that have not already gone to importing a large part of their components may get some breathing room… and some domestic manufacturing jobs may get a reprieve.

And shouldn’t, in classical rhetoric, exports increase and thereby reduce a way-out-of-balance-of-payments?

Given that domestic manufacturers may benefit in both the domestic and foreign markets from a lower valued dollar, “productivity” should increase as less does more with less as opposed to less does less with less… at least for awhile.

Different winners; different losers.

Bruce Hall: Yes, there will be winners and losers. But on net the U.S. will experience a terms of trade loss as the dollar depreciates in real terms, depending upon how it occurs.

If US imports were close to US exports in magnitude, I’d agree that the weaker dollar will induce sufficient expenditure switching so that adjustment would be painless. But imports are about 50% larger than exports…The required elasticities for getting an improvement in the trade balance for a dollar depreciation (without GDP adjustment) is therefore larger than the standard Marshall-Lerner conditions.

Regarding the question I asked in the first comment of this post, I found the answer in a paper from the Fed called “How Biased are Measures of Cyclical Movements in Productivity and Hours?”:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=825631

This paper considers the gap between hours paid and hours worked for salaried employees and what happens when they work off the clock (or out of the office). The key finding is that national productivity data is still a valid approximation.