China, PPP, and Misalignment Estimates

Ever since Albert Keidel wrote in the Financial Times that China was poorer, in PPP terms, than had been reported in the World Bank statistics, I’ve been wondering what the implications are for the Cheung-Chinn-Fujii estimates of CNY misalignment.

In “The Limits of a Smaller, Poorer China,” Keidel wrote:

In a little-noticed mid-summer announcement, the Asian Development Bank presented official survey results indicating China’s economy is smaller and poorer than established estimates say. The announcement cited the first authoritative measure of China’s size using purchasing power parity methods. The results tell us that when the World Bank announces its expected PPP data revisions later this year, China’s economy will turn out to be 40 per cent smaller than previously stated.

This more accurate picture of China clarifies why Beijing concentrates so heavily on domestic priorities such as growth, public investment, pollution control and poverty reduction. The number of people in China living below the World Bank’s dollar-a-day poverty line is 300m — three times larger than currently estimated.

Why such a large revision in the estimates of China’s economic condition? Until recently, China had never participated in the careful price surveys needed to convert accurately its gross domestic product into PPP dollars.

The World Bank’s estimates based on summary data from the late 1980s probably overstated China’s PPP gross domestic product even then. Up to now, the bank has revised its estimate very little. In the meantime, China has repeatedly raised the prices of food, housing, healthcare and a range of other non-traded goods and services. These reforms should have lowered the PPP adjustment, but the bank left it basically unchanged.

…

For China, the correction needs to be made back to the 1980s and 1990s, when instead of World Bank estimates of roughly 300m people below the dollar-a-day poverty line, the number was more likely more than 500m. China has made enormous strides in lifting its population out of poverty – but the task was perhaps more gargantuan than most people thought and progress has been overstated by bank estimates.

These calculations are not just esoteric academic tweaks. Based on the old estimates, the US Government Accountability Office reported this year that China’s economy in PPP terms would be larger than the US by as early as 2012. Such reports raise alarms in security circles about China’s ability to build a defence establishment to challenge America’s.

I’m not sure what the announcement Keidel is referring to, but I’ve noticed that the ADB has just released on December 10th Purchasing Power Parities and Real Expenditures (I think Keidel was referring to the preliminary version [pdf]). In this report, the ADB undertakes one of the first surveys of the Chinese economy, and notes in the highlights:

For the first time, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and India have taken part simultaneously in a regional statistical initiative to compare the purchasing power of currencies and living standards across the region, which accounts for about half the world’s population. As regional “super-economies,” the PRC and India account for a huge 64% of total real GDP of the 23 economies engaged in ICP Asia Pacific. The parallel presence of these two countries has broadened the coverage of this ICP round (the previous round was held in 1993) and will sharpen analytical precision, whether price levels of meat and fish in different parts of Asia are compared, or successful investment strategies in an exceptionally diverse region are devised.

Some interesting statistics are reported for China and Hong Kong, SAR. First, consider what the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) report for the Chinese price level relative to the US and Hong Kong: 0.254, and .345 (all figures for 2005). And for the Chinese per capita income relative to the US and Hong Kong: 0.161 and 0.194.

The ADB statistics do not include the US, but do report the Chinese price level and per capita income relative to Hong Kong: 0.58 and 0.115. One notes immediately that the ADB income ratio of 0.115 is about 42% lower than the WDI ratio of 0.194, and I think this is the number Keidel is referring to.

Assuming the WDI numbers are correct for the US and Hong Kong, one can infer what the Chinese numbers relative to the US would be if the newer ADB calculations are closer to the mark: the Chinese price level is higher than before, and the per capita income is lower than before. Specifically, the Chinese price level is 0.426 (compared to the WDI 0.253) and the Chinese per capita income is 0.096 (compared to the WDI 0.161).

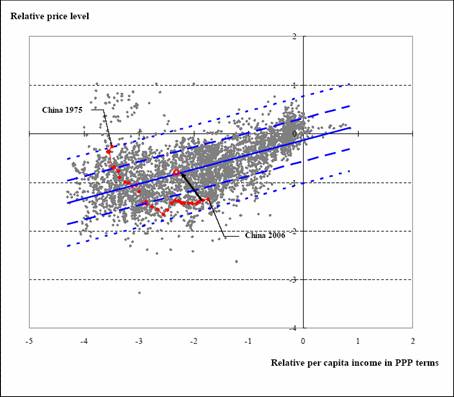

So much for numbers. What does this mean for the Cheung-Chinn-Fujii misalignment estimates? Essentially, the 2005 observation is shifted northwest in the scatterplot graphed in log price level/log relative per capita income space. Reprising our graph, but showing the shift in the 2005 China observation with the black arrow and the endpoint at the red circle, one obtains the following.

Figure 1: Log price level and log relative per capita income in PPP terms, and regression line with +/- one and two standard error prediction interval. Circle is the ADB-implied location of the Chinese observation for 2005. Source: Cheung, Chinn and Fujii (2007), ADB, and author’s calculations.

In other words, these estimates could eliminate the estimated undervaluation according to this PPP criterion. Of course, as I have mentioned on other occasions, the fact that one cannot reject the null hypothesis of no misalignment does not mean that there is no misalignment; nor does it prove that China would not benefit from greater real exchange rate appreciation. It merely highlights how cautious we have to be in making inferences with noisy data.

[On a technical digression, it also highlights the fact that in our previous studies, we were only dealing with statistical uncertainty. We did not directly address data uncertainty, or model uncertainty.]

There are some additional caveats I should make. The first is that there are many subtleties in the PPP literature that I am probably glossing over. It’s not completely clear to me that I can be using the ratios in a manner that assumes transitivity across the ADB and WDI data series. I’m hoping that the violence done to the data is not too great.

The second is that these are solely my own thoughts, and do not necessarily represent those of my coauthors on the Cheung-Chinn-Fujii studies [1] [pdf], [2] [pdf], and described in this post. Third, when the new WDI data come out in April, everything I’ve just written here may be proved wrong.

[Update: Dec. 18, 3:30pm Pacific]

Thanks to psummers for alerting me to this WSJ article on the World Bank’s release of the ICP data. The figures reported in the release, specifically in the tables [pdf] validate my calculations.

However, to see how the trajectory of the CNY is changed, we will have to wait until the new version of the WDI is released.

Technorati Tags: misalignment,

undervaluation,

China,

Renminbi, Chinese yuan,

purchasing power parity,

World Bank,

ADB

How would this relate to the World Economic Outlook Database at the IMF? That also has a PPP series for per capita GDP.

Thanks for extending the argument – the earlier FT piece is one I flagged for myself and blog readers and have been debating with several acquaintances for some time but certainly broadens the aperture.

BtW – have you had a chance to read Greg Chow’s book on “Transforming China” ? A superb study on the various pressures, policy requirements, institutions and some of the best applied economics ever, IMHO.

Putting those pieces together one ends up with a view that the Chinese leaders have a much better grasp on their own problems than anybody outside has given them credit for.

Perhaps at some point you could further explore what this might imply for the Yuan ?

Menzie,

There’s a related story by Bob Davis in today’s (12/18) wsj:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119791516308634301.html?mod=todays_us_page_one

(p. A10 print)

PS

So at least the nominal GDP number for China is correct, right?

This goes to show that PPP is a very bogus notion. If China’s economy is 40% smaller in PPP terms, that means it goes from $10T to $6T, losing a whopping $4T in the process. This means world GDP growth statistics (at PPP) have been overstated for the last decade.

This also means that per-capita, China’s GDP per person is not much higher than India’s.

GK, the reason for the change in China’s GDP estimates is that up until now we didn’t have the detailed price data necessary to make accurate PPP calculations. That doesn’t mean that PPP is a bogus notion at all.

As far as growth rates being overstated, that may be true but then again it may not be. What was certainly overstated was the level of China’s GDP. If the ADB/World Bank/ICP folks had the level of Chinese prices wrong but their growth rate more or less right, then world GDP growth rates would have been more or less right also. Having said that, my impression from the WSJ article was that the rate of price increases in China were in fact underestimated.

PS

psummers: Thanks for the tip. I’ve added an update with links in the main post. I concur with your rejoinder to GK that it’s not clear what the implications for aggregate world growth in PPP terms are. China’s level is lower, and perhaps growth is less, but then China’s share in world GDP is also less.

GK: China’s per capita income in PPP terms is still roughly double that of India’s.

Daniel Dare: I’m not certain, but my impression is that the series are similar, but not identical. See the notes for additional discussion.

dblwyo: Since previously I have stressed the great degree of uncertainty surrounding the estimates of PPP (let alone other statistics) for China, I’m not certain the implications for the yuan changed, from my perspective. From a short-run Mundell-Fleming perspective, I still think more rapid appreciation of the CNY is warranted.

If you are carefully reading Japanese news media, you would have noticed the fact that the number of copper theft in Japan has declined rapidly in this two months. When Chinese economy was really growing, it was easy for those punks in Japan to make money by stealing and smuggling copper and that’s why there were so many copper thefts by this summer. Now there is no demand.

Takashi Beat:

That’s great! It partially proves that PBOC’s tight monetary policy works. The overheating is tamed according to your suggestion.