Mark Thoma notes that the most recent FOMC statement has changed from declaring growth is “likely to moderate” to “Recent indicators suggest that economic growth is moderating”. The first stages of the long-anticipated cooling of the housing market certainly appear to be here now.

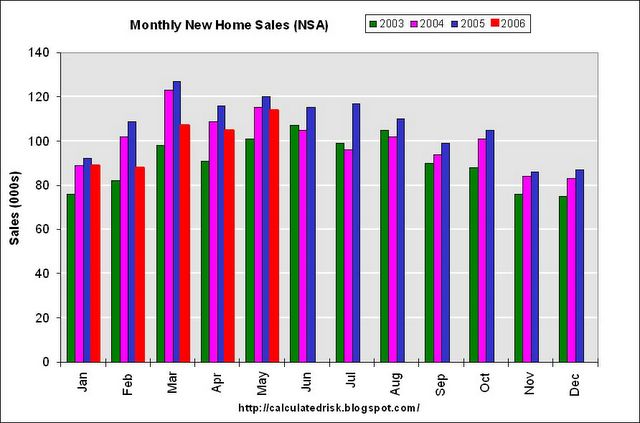

The above graph, taken from Calculated Risk, shows that, for each of the first five months of 2006, the number of new home sales (seasonally unadjusted) has been at or below the value of the corresponding months of both 2004 and 2005.

The inventory of unsold new homes has shot up in response. The graph at the right shows the Census data on months’ supply of new homes, calculated by dividing the number of new homes available for sale by the current monthly sales figures, with recessions indicated by shaded areas. Although this ratio has been declining slightly from its February peak, throughout 2006 we have seen more than a 5-month inventory of unsold homes, which is the highest this series has been since 1997.

It’s unclear how alarmed one should be by that fact, since housing did not play a prominent role in the 2001 recession. A six-month inventory is still below the peak reached in the 1994-95 slowdown, which is perhaps the Fed’s model for hoping to achieve a “soft landing”– just enough of a slowdown to keep inflation under control, without causing a recession. On the other hand, it may be that improvements in information and marketing technology would lead us to expect a lower inventory-sales ratio today than was common in the 1980s. In the absence of such an interpretation, the natural conclusion based on the above two figures would be that we’re indeed seeing no more than a “gradual cooling” as advertised.

The Big Picture notes that the stock market may be anticipating significantly more than this ahead, with the valuations of stocks of homebuilders such as Centex having lost about a third of their value in the last six months.

|

I’m also a little troubled by the pace at which house prices rose during 2005 despite rising interest rates. The June report of the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight claimed that the average U.S. home prices in 2006:Q1 were 12.5% higher than they had been in 2005:Q1. The state-by-state breakdown is as follows:

|

In the first quarter of 2006, we saw the rate of price increase moderate slightly from its 2005 pace, though prices still rose rather than fell in almost all states, and the annual rate of increase remained at a double-digit pace throughout the west.

|

That last fact is a bit disconcerting to those of us who attributed the rapid house price increases of recent years to the low level of interest rates interacting with regional growth and limited local supply. If interest rates were the key driver, I would have expected to see the rapid price appreciation stop by 2006:Q1. And if real estate was overpriced in 2005, there is that much more that needs to be unwound now. Granted, price is a lagging indicator, and there is first an increase in the length of time houses stay on the market before one sees prices start to fall. But the OFHEO statistics suggest to me that a recognition that the heady days of rapid real estate appreciation are now over had yet to sink in as of the first quarter of this year.

That troubles me, because it raises the possibility that, when the recognition does sink in, the current “gradual cooling” could quickly turn into something more impressive.

Technorati Tags: housing,

Federal Reserve,

recession

I often wonder how much of the housing inflation is owed to the fact that many municipalities have never met a costly housing regulation they didn’t like. Every time they pile another one on, existing owners are that much happier. And non-owners don’t get a vote, because they’re zoned into some other municipality.

Yesterday the 30-Year Treasury closed at a yield of 5.18% vs. Fed Funds of 5.25%. That’s a negative yield curve. This week has been the first negative number since the 30-year bond was re-introduced.

M2 growth remains anemic at 1.4% as of Thursday’s Fed report, down from 8.8% when Mr. Bernanke took over at the Fed.

Unless those two indicators reverse direction quickly and substantially, we’re going into a credit crunch and recession. Housing will weaken further.

I’ve always thought that one of the reasons for the housing bubble over the last few years was that, after stocks stopped being such a sure thing, there was still a lot of money around that, like the boll weevil, was “just lookin’ for a home”.

Isn’t that what you’d expect as wealth becomes concentrated in fewer hands?

It’s sort of vaguely reminiscent of global warming. As more energy is put into the global weather system supports greater volatility in weather, so more money in the system supports more bubbles as investors flock to the next sure thing.

House. we don’t need no stinkin’ house!

Isn’t that what you’d expect as wealth becomes concentrated in fewer hands?

No. I’d expect an increase in rent-seeking. Concentration of wealth does appear occuring to some extent, but it’s not causing this. Investment bubbles are more a sign of limited knowledge. That is, there is a class of investor who is over-estimating the return on various types of investments. I wager that investment bubbles are probably one of the causes of wealth concentration rather than the other way around.

Stating the obvious, the bottom line is affordability. The cost of a home is different than the price. At low interest rates, housing can appreciate in price because the cost of ownership is low. When the price of money increases as a result of asset inflation, the cost of housing increases, putting downward pressure on housing price.

Rent-seeking is rampant on the futures exchange. Big money is driving the price of commodities to extreme levels, causing the lagging inflation measures to accelerate. I think inflation expectations have become “well anchored”.

Inflation is created by “rent-seeking” and the leading indicator is asset price inflation. The best correlation I have seen can be seen here:

http://www.crbtrader.com/crbindex/futures_current.asp

Belatedly, the Fed is forced to be reactive rather than proactive, maximizing the damage by the collapsing bubble.

I am becoming convinced that the futures market is not an efficient price discovery vehicle. It is more of an organized crime vehicle through which the “rent-seeking” wealth fleeces the public by driving up the price of basic commodities using paper contracts to create and dominate bubbles. This is a system that is out of control. When one bubble collapses, other bubbles will follow.

We may soon get an opportunity to see which markets are actually bubbles and which aren’t.

I don’t know about house prices, but I do follow house starts in the USA closely. Have a look at the new orders of the listed builders. Most of them are down around 30% on PCP for the 2-3 months ended May. That’s an acceleration in the pace of decline as compared with the 10% fall in the quarter to March. Tx appears to be doing better than CA and FL in that respect with those 3 states accounting for about 27% of USA starts from memory.

Most of the evidence I look is consistent with a 20% decline in housing starts from 2005 peak over two years. In other words a hard landing for the USA in housing starts is on the cards.

“That troubles me, because it raises the possibility that, when the recognition does sink in, the current “gradual cooling” could quickly turn into something more impressive.”

I think Soros called this “reflexivity”, or the fact that prices tend to hold their trajectory long after fundamentals have changed.

I would also add, that homes may still look to many buyers like a safer harbor; compared to riskier investments, such as: commodities, stocks, emerging markets.

But, why not hold bonds instead? Are there that many investors prefering to hold hard assets because they’re still expecting a USD drop?

I’m more inclined to think it’s number 1 with a touch of number 2.

Here in California, with seemingly inexhaustable population pressures and hence demand for housing, I’ve often observed that you either pay the seller or you pay the banker.

That is, with low interest rates, prices escalate. With high interest rates, prices are largely stable but your interest payments increase.