In order to export in a competitive market, we need to import

In a previous post, I discussed the role of vertical specialization or production fragmentation in distorting measured trade flows. A recent National Research Council/National Academy of Sciences report examines the extent of vertical specialization. In particular, they address the questions of how much import content is there in U.S. exports, and the U.S. export content in U.S. imports. For the former, consider the example given:

‘An example helps to clarify some of the issues involved. Consider the

production of an engine for a U.S. automobile for export to Canada. It is more than likely that many of the components of the car’s engine will be imported to the United States for incorporation into the engine. These imported goods are likely to be combined with domestically made parts to assemble the various elements of the car engine. In addition, the automobile company may decide to outsource the assembly of the complete engine to a factory in Mexico. Therefore, the company exports the engine parts, which have in them both domestic and foreign value, to Mexico, where they are assembled into the complete engine that in turn is imported into the United States for assembly into the car. The car is then exported to

Canada. The splitting of the production of the car into separate processes carried out in different locations is called fragmentation. This kind of production process leads to the question: With value originating from so many different countries, what part of the car that is exported to Canada is American? Indeed, what part of the engine imported into the United States during the car’s production is American? Aggregating these questions across the economy, the question becomes: What is the U.S. content of the country’s imports and the foreign content of its exports? What does “Made in the U.S.A.” mean in the 21st century global economy?’

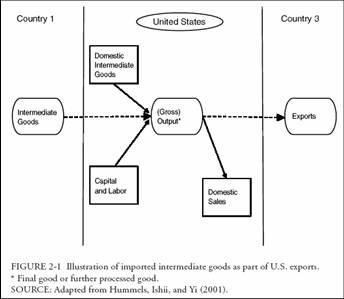

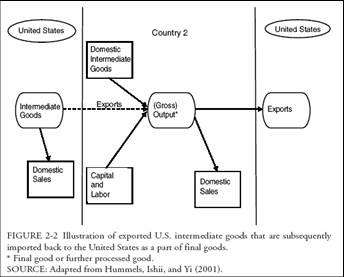

While the authors conclude that one can’t answer the second question — the U.S. content in U.S. imports — they do take a stab at the first. Of course, there are complications, as illustrated by the two schematics representing possible instances of fragmented supply chains.

Source: NRC (2006)

Source: NRC (2006)

In general, the data are not up to the task of teasing out import content. Under a variety of simplifying assumptions (including the assumption that U.S. imports have no U.S. content), Kei-Mu Yi makes the following calculations of the import content of U.S. exports.

Source: NRC (2006)

Presumably, since 1997, the import content has increased. However, figuring out how much is probably a difficult task.

Technorati Tags: trade deficits,

vertical specialization,

production fragmentation,

supply chain,

import content of exports

Presumably, since 1997, the import content has increased. However, figuring out how much is probably a difficult task.

The key issue is value added in each location which presumably would be easier to track & carry through. However that opens up the issues around phony transfer prices & intangibles.

If you had sound data it wouldn’t be that hard to calculate, model & track in the real world – mathematically similar to mass & energy balances in recycle streams around a reactor in a chemical plant… well established algorithms for solving found in any Chem Eng intro text.

The problem will be getting reliable data. There will be data – but with transfer pricing & intangibles involved, I wouldn’t necessarily trust it.

dryfly: The article referenced lays out how ideally one could calculate the ratios — so I agree the algorithm is clear (although once one departs from Leontiev production functions, it isn’t so clear). As they indicate, the problem is with the data collection systems.

Would it be right to assume import content of the exports from a country such as China would be considerably higher than what is in the table above? And I wonder how much of that import content comes from the US and whether it is or isn’t a negligible factor in the trade balance.

Hi –

This direction helps immensely in trying to understand those industries and countries that have, for instance, import and export quotas well in excess of 100%, i.e. the re-exportation problem. Thanks!

John

BAL: Yes, I think it would be safe to say that the import content of Chinese exports is substantially higher than for US exports. I discuss some of the evidence in this post.