Does the market price of oil reflect a recognition that the resource is fundamentally limited?

Dave Cohen, writing at the Oil Drum, has been doggedly wading through the writings of economists on resource scarcity, going the extra mile (and then some) trying to understand how those on the other side of the river from him have thought about the issue of resource scarcity.

As Dave nicely explains, the traditional Hotelling model reasons that market forces will cause there to be a “scarcity rent” incorporated in the price of an exhaustible resource. The observation is that someone who sells a disappearing resource today is thereby surrendering the opportunity to sell that commodity in a future market in which it might be more highly valued. As a consequence of owners bringing more or less of the product to the market at each date on the basis of such calculations, the theory predicts that the scarcity rent should rise over time at the rate of interest.

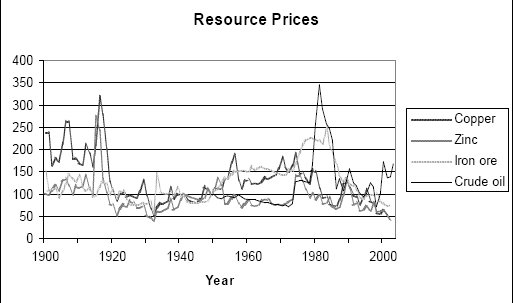

Dave then runs into the same stumbling block as anyone else who has tried to apply this elegant theory to reality– if you look at the inflation-adjusted price of what should be exhaustible commodities over the last century, there’s no hint at all of an upward trend:

|

Dave concludes that sellers have been regarding the day of exhaustion as so far off in the future, that, given also advances in the technology of extraction, a scarcity rent has made essentially no contribution to the price. But Dave’s geological assessment is that in the case of oil at least, declining annual production rates in fact are going to come relatively soon. He concludes that perhaps the scarcity rent is not making the contribution that it should for oil due to possible factors such as investors too heavily discounting even relatively near-term events, or deliberately misleading data provided by oil producers such as Saudi Arabia in a strategic game to prevent investments in alternatives to conventional oil reserves.

My own view is that, for most of the past century, Dave’s inference is exactly correct– the resource exhaustion was judged to be sufficiently far off as to be ignored. However, unlike those whom Dave terms the Cornucopians, I do not infer that the next decade will necessarily be like the previous century. Certainly declining production from U.S. oil reservoirs set in long ago. And if one asks, why are we counting on seemingly geopolitically unreliable sources such as Iraq, Nigeria, Angola, Venezuela, and Russia for future supplies, and transferring vast sums of wealth to countries that are covertly or openly hostile to our interests, the answer appears to me to be, because we have no choice. Resource scarcity in this sense has already been with us for some time, and sooner or later the geological realities that governed U.S. oil production are also going to rule the day for the rest of the world’s oil producing countries. My expectation has accordingly been that, although scarcity rents for oil were irrelevant for most of my father’s lifetime, they would start to become manifest some time within mine. And I have been very interested in the question of when.

|

If Dave had gazed not at a century of prices but rather at just the last 15 years of the price of oil relative to the PCE deflator, would he have drawn the same conclusion? If all we had was the graph above, it would seem quite natural to conclude that a rising scarcity rent could well be one factor in the recent behavior of this commodity price.

To be sure, there are some facts that fit a bit messily into that picture. One is that, over the last several years, oil futures prices have exhibited backwardation at some horizons. This is less dramatic now that it was a year ago, with the six-year-ahead contract price of $64 a barrel now above the current $59 1-month-ahead price. It is not obvious how to reconcile the behavior of futures prices over the last several years with a scarcity-rent explanation, though possibilities to investigate might be option valuation, adjustment costs, or hedging or other risk premia.

A separate set of doubts of course arise from the dramatic plunge in oil prices over the last few months, which at a minimum must reflect either some substantial new information about the long-run fundamentals or else confirm that some factors other than scarcity rent have been contributing to the oil price peak of the last year.

Despite these observations, I am not at all prepared to dismiss the hypothesis that scarcity rents have indeed started to make a contribution to oil prices over the last five years, and will become more apparent over the next five. For example, the announced intention of OPEC producers to cut back production as the price goes below $60 might be most naturally interpreted from that perspective– producers don’t see it as being in their interests to sell for less, given what the oil will be worth in the future.

Admittedly, if the oil price should fall from here down to $30, then I’ll have to conclude that scarcity rents have had nothing to do with the recent price moves.

But if Dave is right about the geology, oil is not going to $30.

Technorati Tags: oil prices,

peak oil,

Hotelling

Oil, Peak Oil, and Recent Price Declines

James Hamilton has a nice post, quoting David Cohen of The Oil Drum. He explains the standard economic argument that the price of a finite resource being depleted should rise at a percentage rate equal to the rate of interest.

Nice summary. But I think the price data support the view of a market with two facets: 1) occassional use of monopoly power by a cartel, and 2) long time lags to bring new production to market, then long time lags in the decay of production volumes.

When I look at the oil price data, my eye keeps coming back to 1986. (a chart is at http://businomics.typepad.com/businomics_blog/2006/10/oil_peak_oil_an.html) I think prices are headed down, though timing is hard to pinpoint.

How do things like time value of money come into play? Future return has to be discounted. The further out, the heavier the discount.

Also for the capital intensive mining (oil/gas included) how much choice does a producer heavily loaded with debt have? How about countries that rely on natural resource exports to feed their people?

It certainly seems that this time around the resource rich countries are getting the upper hand, but neither oil/gas nor metals are truely irreplaceable in the long run. And metals aren’t even really consumed for the most part.

Sorry. I see the idea is based on discount rate.

In the long run in which we are all dead, the price of exhaustible fuel goes up, period, with the only question being by how much and when. This certainty does producers and investors no good if they are sitting, say, in 1981. In the short run demand matters, quite a lot on occasion, and price and inventory data have been telling us for months that demand has slackened.

However — and I say this as a short-term oil-complex bear — there is essentially no way that 1986 happens again. If you do not know the history, two seconds with Google gave me this page, which conforms with my memory and seems a decent synopsis:

In the short run, Dave can be right about the geology (indeed, I believe he is) and you still will want to be short or at least underexposed to energy as US production and consumption weaken. We do still consume 25% of the world’s crude production. When GDP is slowing (wait ’til Friday, I know, but I am pretty sure), crude dropping and stocks rising, you might wait a quarter or three before overweighting crude once again.

Two quick little pictures from the ever-useful EIA. Here were crude stocks in 2002 (GIF) with WTI at $30. Here are stocks now with WTI at $60.

Is crude going to be over $100 and extracting nice scarcity rents? Sure, probably sooner than we like. This coming year? I wouldn’t bet on it.

Bill, I don’t see how your cartel-centric analysis holds at all. Clearly, by looking at the same chart you present as evidence, the behavior of the market today is qualitatively different than in 1986. We don’t have discrete jumps in price like that anymore because cartels are less influential for a number of reasons:

I’d also pose this question: what was China in 1986? A blip. What will the US be in 20 years? A blip — in a world of much greater demand.

Another trend people tend to forget in the analysis is the steadily decreasing EROEI (energy return on energy input) of oil extraction. This is compatible with the notion of long-term price oscillations — but it means the floor of those oscillations gradually increases. The change in EROEI is physics-based; it cannot simply be undone by having periodically higher prices.

I think hedge funds had the bet right over the past year. Oil should be closer to $80 than $50 — and will soon move upwards signficantly.

Maybe we should view oil (and other resources like water in an aquifer) like manna from heaven. It’s very cheap when universally available but then it starts to run out and the price suddenly jumps. Maybe we have a scarcity rent only to the extent that owners anticipate the coming shortages – which I don’t think is happening that much.

Is peak oil irrelevant? How can you even ask such a question? Look at all the books it has sold. It is a theory looking for a publishing advance, but beyond that, naw, not much relevance.

No peak oil discussion ever mentions the restrictions we have placed on our ability to develop oil and gas resources in this country. Why search for the stuff when you know that government will not allow its development?

The recent find in the Gulf of Mexico makes you wonder what is lying under lots of places where drilling is curtailed.

These decisions might have been the right ones, but they do have an impact and I’ve never seen them addressed. Is it just me?

The most important factor in the price of oil is inflation. Oil at early 1970 prices relative to the economy would be around $30-35 today, but when Nixon floated the dollar oil prices sold at a premium to hedge against currency changes. Building in the hedge the price of oil today should be around $45-50 today, but that does not take into account the additional premium due to the chaos created by FED monetary policy, the IMF and World Bank negative impact on world economies, the increased worldwide demand, and unrest in the ME. It would not be unusual for oil to come down to the $45-50 range, but at current inflation it is doubtful it will drop much below this level. And all of this has nothing to do with peak oil.

Dan,

Even if the best estimates are correct and we could suck the gulf find as fast as possible, it would be gone in 3 months. The point to peak oiil isn’t so much it’s running out, (though it is), but more that what’s left the find (we have looked everywhere except the shelf) is really expensive to get at and all the easy oil has been depleted.

Also this is not a “theory” it is a geological fact. Every individual oil well follows a bell curve and when you hit peak production you can do nothing to increase production no matter how many more wells you drill. You can’t price your way out of this.

This is where economics has no real answer b/c there will be no substitute that holds the same energy content for anything near a similar price. We need to reevaluate our transportation system from top to bottom. We waste so much energy on so many needless things that we’ve been convinced we need.

Dick – If the most important thing to oil is inflation, (it’s not), then the only thing that matters is the money supply. Inflation only happens in a fiat system when the MS is increased and worse when it’s nefariously hidden.

I should also mention that there are two ways the significance Peak Oil is misconstrued:

The only meaningful sense of Peak Oil that matters (i.e. for prices) is the margin of supply over demand. It is the peak in this margin that signals the beginning of a steadily-higher price regime. Even if output grew at a steady 3% a year (i.e. no peak), a shift to global demand growth of 4% a year would imply a steadily shrinking supply-over-demand margin at some inevitable future inflection point.

#1 fails because production is not in-ground supply (reserves); if production manages to increase even when reserves are dwindling, there will be plenty of supply above-ground (on the market). This would imply low prices.

#2 fails because demand could slow down enough (or even fall), having the same effect: more spare supply on the market, thus lower prices.

Many critics realize that these two views of Peak Oil are flawed, and latch upon it, pointing out that in a recession, “demand will fall”, which will create effective excess supply, which will cause prices to return to lower levels.

The problem with this view is it is based on a historical regime where US and Europe were the dominant sources of demand. Now, tons of demand growth is coming from Asia. This suggests to me it is unlikely that demand growth will slow enough to allow supply margins to grow significantly — even in a recession.

(In fact, I think we’re in a recession now.)

One other element missing in the Hotelling model is technological change. Improved methods of recovery have also probably played a role in holding off the Hotelling scarcity rent increase.

Just a small point relating to the Resource Prices graph: I would not mix metals with oil, as, unlike oil, the supply of basic metals is inexhaustible and limited only by the technology and labor costs. Oil is burned up and disappears, basic metals can be 100% recovered. In this sense, fossil fuels and radioactive metals are the only exhaustible resource we use.

http://smallinvestorchronicles.blogspot.com/

Barkley

As I recall, in the Hotelling Model, technological change (better extraction) can actually drive *down* prices.

In the postwar period, this is what appeared to have happened in oil. The successive revolutions brought on by the Schlumberger patents in wireline logging, geophysical mapping and (1980s and 90s) horizontal drilling and 3D real time modelling.

Since these drive prices *down* ironically they may bring forward the day when the commodity is exhausted.

The other form of technological externality in Hotelling is the ‘backstop’ technology, which sets a ceiling price on the resource at which point the backstop becomes economic (Canadian Oil Sands as an example at c. $30/bl).

Again this causes faster consumption of the resource. The market knows there is an alternative, so it burns through the resource faster. The time path has a lower slope.

This is, I suspect, part of what happened in the 80s and 90s. Sheikh Yamani was famous for saying ‘the stone age did not end because we ran out of stones’ and the 1974 and 1979 oil crises had spurred so much new production, conservation and new energy sources, that the market assumed (rationally) that oil exhaustion was not going to be a problem.

Alex

Metals are not inexhaustible in the sense that there is always wastage and material that cannot be recovered.

They are inexhaustible if you presume infinite energy: sea water is rich in minerals at very low concentrations.

Few comments:

1. Douglas Reynolds at the University of Alaska has been looking at this issue. E.g. “The Mineral Economy: How Prices and Costs Can Falsely Signal Decreasing Scarcity.” E.g. he says that it is possible that “True scarcity is only revealed towards the end of exhaustion.” He’s collected his papers together in “Scarcity and Growth Considering Oil and Energy: An Alternative Neo-Classical View”

2. I think the title of this post is a bit misleading. “Is peak oil irrelevant?” should say “Is peak oil irrelevant to the current price of oil?” Or better yet, I would go with a more affirmative view of peak oil, asking “Is peak oil relevant to the current price of oil?” I agree with JDH’s mention that yes, it could be.

3. Dick: We can remove all the inflationary issues you mention. We’re not considering inflation here. We’re looking at real prices.

4. I put my two bits in with JDH’s comment: OPEC production cuts while oil is at $60 is a sign of scarcity rents. It is in the interest of the oil producers to gently move the price of oil up to new price levels if in fact we are approaching peak oil production. For all we know, OPEC has already decided that each barrel is really worth $100 but they need to let the world absorb $60 for a while.

5. Unlike JDH, I’m not willing to read that much into the futures market and recent price drops. It could be noise and irrational speculation from my perspective.

6. If oil goes down to $30, I’m not sure whether to be happy or depressed. I’m long at around $30 and less so at $55.

If you run your price of oil in 2006 dollars back to 1980 it was roughly $100 at that peak.

My question is if we are really at peak oil production why is the real price of oil 30% lower now than at the peak in 1980?

Spencer: Good question, but I think the answer is that the price in 1980 was overtly political. There is no doubt about that. Even the sudden price increases at that time scream out “political.”

We’re not seeing that now. We’re seeing prices more slowly move upwards, with some noise. Production remained largely constant with consumption rising up towards production. A totally different sitation than 1980.

After the two earlier oil shocks, new sources of oil were developed. We will see the same now, no doubt, but I think geology is making a stronger argument against a new North Sea.

If I was a large producer of oil, and I thought production might be peaking in the coming years, I would do the following: (1) allow consumption to start running up against production (2) let prices increase (3) create an atmosphere of uncertainty (4) see if anyone starts producing in a way to pop the price bubble and see if demand drops dramatically (5) start investing in new sources of production if price remains steady and (6) go back to 1.

Well also one should consider that the current controllers of oil may be worried about their ability to maintain control of their oil. Therefore, they may want to extract it sooner, rather than count on having it later. I’m not sure how that would be incorporated into this model.

Dick – If the most important thing to oil is inflation, (it’s not), then the only thing that matters is the money supply. Inflation only happens in a fiat system when the MS is increased and worse when it’s nefariously hidden.

Patrick,

Partially right. We must also look at monetary demand. This is where the FED has its greatest impact. Its expressed intention is to reduce growth to the point that businesses begin to reduce monetary demand, in other worlds when businesses begin to fail.

3. Dick: We can remove all the inflationary issues you mention. We’re not considering inflation here. We’re looking at real prices.

T.R.,

My entire post was about real prices.

Most seem to be missing the most important point. Oil is nothing but a source of energy and a very cheap source of energy. If the supply of oil becomes less than demand, substitutes will began to enter the market. As has always happened necessity will make alternative energy sources more economical and oil usage will naturally decline.

It is not an all or nothing issue, meaning it is not all oil or all substitute. There will always be a mix of energy sources with the least expensive being dominant.

In analyzing this issue I suggest you use the principles in Henry Hazletts Economics in One Lesson.

The question seems to be why we have not thus far seen much evidence of scarcity rents. The concept is predicated on the assumption of rational actors trying to maximize profits over the long term by reducing oil production in the short term. But what if they are not acting in the way predicted. I can think of at least two possibilities.

1. They aren’t worried about the long term. For example Chavez only cares about winning the next election, the Saudis are only concerned about appeasing restless radicals, and the chairman of Chevron only cares about maximizing profits for the next two years and so he can cash in his $400 million golden parachute. Better to earn a dollar now than later.

2. They simply misjudge or willfully dismiss future trends in oil production. Evidence for this possibility is the recent history of Ford and GM who behaved as if gas guzzling SUVs would be in demand forever. They simply didn’t believe in scarcity. Perhaps oil producers think the same.

Dick: I understand that your post was all about real prices. What I’m saying is that we can easily put up a graph with the real price of oil and continue the discussion without trying to “explain” what is going on in terms of inflation. When we look at the real price of oil, e.g. here:

Real and Nominal Oil Prices” we see that real oil prices are starting to get expensive.

The most important point about energy right now is not inflation. You said as such and it isn’t true. And that statement is misleading to readers who might not have considered this issue.

As far as basic economics, you’ve simply not said much regarding oil and where it is headed. We’re all familiar with energy transitions in the past, the power of markets, innovation, etc. etc. But those generalities have no specific bearing upon (a) our ability to predict the price of oil and (b) the specific of how the price of oil will actually move in the future. At what price will we see alternatives kick in? What are the alternatives? What will be the cost of replacing the existing industrial infrustructure to accomodate these new energy sources?

More questions than answers. It is very easy to make blanket statements based on a few historical anecdotes, e.g. previous energy transitions. But they aren’t proofs. They are inferences based upon only a few data points.

I messed up putting in the link. It’s to Forbes. It even makes sound. Wow. The power of the internet.

Real and Nominal Oil Prices

this is a very simple fact – but it is the one which eludes the peak oil faithful : industrial activity, oil, and the price of oil, are not linear – but circular. the peak oilers imagine expanding industrial activity (the rise of china and india etc.), declining oil production, and thus escalating oil prices. but escalating oil prices shut down some industrial activity and some private consumption. it is perfectly possible for the oil price to plateau, while both oil production and global industrial activity gradually contract.

o yes, we can find more efficient oil using technologies, alternative energy technologies, and even (shock, horror) submit to cultural change – but in those cases the demand for oil declines, even though growth in industrial activity continues in alternative directions.

next time you are travelling in your car, gently lift your foot on the accelerator. you have now subjected your vehicle to a peak oil scenario. the flow of gas/diesel to the engine declines. the price of the fuel in your tank does not go up – your car slows down.

‘peak oilers’ are proposing that the car continues to accelerate as the fuel supply decreases. i e that demand can get higher than supply. i wait with interest to see it happen . . .

Thanks for the response T.R. I can’t give any real predictions other than what I have posted because I do believe that the primary problems with the price of oil stem from monetary problems rather than peak oil problems.

In the mid-1990s (also see the late 1980s) we had a FED generated deflation that knocked base commodities down. They became unprofitable and so investment shifted elsewhere. What we are seeing now is the result of this. Producers were reluctant to get back into oil production, political considerations closed down marginal wells and prevented many new finds from bein tapped. The government is more intrusive in the oil business than almost any other (similar to health care and education). This intrusiveness distorts the market such that it is almost impossible to predict unless you can see the future.

If the price of oil continues as high as it has been then I expect more oil glut and a decline in the price, but much of this is dependent on the intrusion of the government and the FED’s lack of control of the money supply.

This is a great topic, and I do encourage people to read Dave Cohen’s posting at TOD, it goes into a lot of detail.

One issue Dave doesn’t go into is that for much of the 20th century, oil production has been effectively controlled by cartels. In the first part of the century it was the Texas Railroad Commission, and in the 2nd part it was OPEC. Cartels restrain production and prevent producers from responding to the Hotelling incentives, which basically call for overproduction in order to maximize the up-front cash flow from the oil.

Since the 80s the OPEC cartel has largely collapsed. If you analyze what should happen in the Hotelling model, we would expect to see an increase in production to a peak, accompanied by a drop in prices. From that point on we expect production to decline steadily and prices to rise steadily. Looking at the history from 1980 to the present, it’s not that far off.

Note that the peak in this context is not because we can’t produce any more, as Peak Oil doctrine has it, but because producers want to maximize the net value of their diminishing resource. That seems basically consistent with recent comments from OPEC and others.

Note too that there is no need for a cartel in this model to achieve restraint of production. It is in each producer’s individual interests to hold back, because he expects oil to be worth much more in the future.

Now as JDH points out this does not quite match current futures prices. Here’s a “price strip” I made manually over the weekend:

http://alumnus.caltech.edu/~hal/oil20061020.png

It shows oil expected to be about 20% higher two years from now, then falling back gradually over the next few years. I’ve never understood why the futures strip has this shape, but it’s been roughly like this for the past few years, I understand.

“Is peak oil irrelevant?”

The answer for now is YES. Period.

What is the economic structure when you have some oil producers who “believe” in peak oil (scientific-fact based) in competition with some who don’t, or who have distinctly different motives?

It seems like the result is similar to a cartel member (the peak-oil understanding actor) losing out to the cartel buster. The parallel consequence is that the “smarter” one (who still needs income) will have to start drilling and pumping at a higher rate than is desirable.

This works only up until the point that literal physical capacity and geophysical reality make production increases literally impossible, rather than unwise. Unfortunately this may be too far down the road for the price signals to give a true assessment of the situation and stimulate alternative substitutes early enough to avoid a really major problem.

Matt,

I lived through the “oil crisis” created by the Nixon administration and it was no fun, but the aftermath proved that the market actually will do what government coercion never can. Crisis thinking about energy always assumes that people are stupid enough to destroy all of their current sources of energy before the find alternatives. This simply makes no sense when you look at the real world.

The miracle of the free market economy is that people are always looking for profitable alternatives. Because of this if the market is allowed to work we will never see a situation where alternatives are delayed until there is a real problem. The only way we will have another energy crisis is to have another Nixon administration create one.

Sorry to reply to myself but I want to add that peak oil is only good for selling books. Even if the claims are true this is virtually meaningless in a world of free markets. We have almost an infinite number of energy sources. Remember that the dominance of oil in energy production is just a little over 100 years old.

I can reply to Dick, given my plentiful resources. And save him the trouble and, of course, the cost of depleting his perhaps more limited resources.

This sentiment

tells us that we live in America not the Sudan or even Nigeria. If you act before midnight Oct 29th I can spell this out in excruciating detail for a mere $9.95, otherwise you will miss out on this enlightening opportunity. [For those of you who know the Enlightening Market is seriously depressed and think I’ll get few takers, I throw in my guarantee of 100% satisfaction or money back.]

Dick: I think you already stated this, so “add” is the wrong word. “Repeat” seems more appropriate.

So I’ll repeat. Your argument is an inference based upon a few historical energy transitions. A handful at best. The transitions can be counted on two hands, by and large. Second, we don’t have an ininite number of energy sources. Nor do we have “almost” an infinite number.

More accurately, we can state the following: (1) Humans have relied on a few sources of energy during their 10,000 or so years of civilization. Maybe ten. (2) There are only a handful of energy sources available to humans. 20 is probably a good estimate. Not infinite. (3) Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Last time I check, free markets operate under the laws of physics. As someone very interested in the philosopy of science, I understand the tenuous natural laws. But I also don’t jump out of buildings thinking I can fly. So I’m looking at economics AND physics, not economics in a vacuum.

People who say “free markets” will solve all problems forget don’t mention that truly free markets are darwinian, by and large, and when necessary, they solve problems in ways we might find distasteful. I’m not saying free markets can’t solve the problem of peak oil, but the Nobel prize winner Richard Smalley said humans will need 5 miracles to overcome the upcoming energy crisis. He supplied his argument with good factual analysis.

Saying free markets will solve all problems is “virtually meaningless” and as a private investor I would say worthless. I’m interested in facts, not platitudes about free markets.

I agree with Dick and am amused (but not surprised) by T.R.’s analysis. I think that Dick is on firmer ground pointing to historical transitions. I would like to hear of any counter-examples where transitions failed (on a global scale, not just local examples).

The market provides incentives to problem solvers. As the price of one resource rises, the desirability of alternatives increases and the search for new alternatives steps up. We will never run out of oil – it will be superseded by alternatives well before the barrel is empty.

imagine drinking a soda out of a straw. you feel no difference whether it’s almost full or almost empty.I agree with the quote above by D Reynolds “true scarcity is only revealed towards the end of exhaustion.” R P’s “horrible sucking sound “, is going to have a whole new meaning.As far as recent price drops, that’s because lots of speculators were waiting for the big hurricane in the gulf that never happened. panic selling, no one wanted to be holding the bag, or the last one out the door.

T.R.,

Thanks for the response. Unlike lp I believe your response was reasonable and respectful.

I do respectfully disagree with your assessment of energy sources. One of the reasons you do not see more sources exploited is because of cost. If a source cannot compete one would be foolish to engage in its production.

I also respectfully disagree that the free market is Darwinian in the way that you mean it. The free market is a survival of the fittest, but the fittest do not succeed in the market by selfishly destroying others. The fittest in the market succeed by providing better quality goods and services to others at a better price. The fittest in the market is not the one who is best at devouring others but the one who is best at serving others. If you doubt this simply look at your on motivation to buy goods from a particular business. For example, I will drive past a home improvement store so shop at one that will give me good service.

But I guess only time will prove one of us right concerning energy.

I’d like to make a few definitions, so that everybody means the same thing, while we discuss.

“Peak Oil” doesn’t say that we will run out of oil or that oil will spike in price. “Peak Oil” only means that: For any given field (or for the whole world), there will come a moment when current production exceeds new discoveries. This does have economic implications, but what they are depends on lots of factors such as inflation, cartells, conservation etc. And most importantly, it does NOT say that demand will ever exceed production.

Example: We have exceeded peak Coal, but prices have gone down.

Peak Oil is merely a Law about Geology and extraction physics.

B

This peak oil energy discussion do become repetitive and tedious, I must admit. But I think there is room for constructive response (though repeated ad-nauseum across the internet).

1. The free market builds and destroys. My point is simple. Free markets cannot do the impossible. Science, contrary to what most believe, is about limits. The speed of light, for example, is a limit. And then operating within the limits. Free markets cannot operate outside those limits. That’s what ecological economics is all about. Nobody, and I repeat, nobody, knows what the approximately 8-10 billion people in the year 2100 will be doing for energy. The fact that people in 1800 didn’t know either is not proof that we don’t have a problem. “Gee, it worked out for them” isn’t sound analysis. It simply isn’t an argument, and to pretend otherwise is to enter the realm of faith and religion, not science. By the year 2100 (and well before) humans will have worked their way through most of the easy energy. Creative destruction has, in the last few hundred years, operate in a way that produced some suffering at the micro level but significant growth and benefits at both the micro and macro level. We simply do not know what society will do if the amount of energy available to us decreases yearly. Creative destruction may seem less creative than destructive.

2. Previous energy transitions do not play much or any role in arguing about future energy transitions. The previous energy transitions went from sources with lower energy density to higher energy density. The world didn’t end because it ran out of coal. It found oil and natural gas–and uranium. There is no next energy source on the horizon. And there is a difference from previous transitions. Science has made significant progress in modeling and basic physics in the last 100 years. If there was a magic energy source, we’d probably know about it. And we’d already be playing around with it.

3. As far as the market providing incentives to problem solvers. True. But that doesn’t say anything appreciable. It’s sounds great as a talking point and in political speeches, but I don’t invest by considering that “markets provide incentives to problem solvers.” I invest by looking at the facts and largely ignoring the platitudes. About 15 years ago, my analysis told me that cellular was the next big thing and QUALCOMM seemed to be the place to be. With luck, that analysis paid off big. About five years ago, my analysis told me that energy was the place to be. That analysis has also paid off big. Investing is a lot of luck combined with good analysis–and ignoring the pundits, most of whom are good examples of the pter principle in practice. And with that as background, I’ve been looking at the energy issue pretty closely for about five years and I still think the human race has some problems. My gut tells me this century ain’t going to be pretty.

I prefer the following definition of peak oil, which nearly everyone seems to miss:

Peak Oil refers to the maximum rate of flow, not the quantity, of oil.

I think people who understand calculus grasp this concept immediately, whereas the majority who never went beyond algebra, don’t.

Let me respond to Matt’s question about what happens when some oil producers believe in Peak Oil and others don’t.

Let’s suppose we have Cornucopian Charlie, who assumes that oil will continue to be plentiful, and Doomster Dave, who believes that a major Peak Oil crisis is on the horizon. They both own oil fields.

Cornucopian Charlie believes that oil will continue to be moderately priced into the foreseeable future. He doesn’t see much point in conserving his oil field as he doesn’t expect much appreciation. He develops his oil quickly, subject only to geological constraints so as not to damage productivity too much.

Doomster Dave believes that oil prices will go through the roof in a few years when shortages hit. He saves his oil for when it will be far more valuable, producing only enough today to cover minimal costs and expenses.

So, in the short term, Charlie produces heavily and Dave husbands his fields and produces little.

Now, who does well in the long run? Well, that depends on who is right. If Doomster Dave is right and we see a serious Peak Oil crisis, he’ll be in good shape. He saved his oil and now he has plenty to sell at very high prices. Charlie on the other hand has depleted his fields and has only a trickle left. He wishes he hadn’t wastefully sold all his oil for a pittance.

OTOH if Cornucopian Charlie is right, and prices remain moderate, he does very well. He makes a good income from his oil and is able to invest that and live well. Dave on the other hand has saved his oil for a rainy day that never came. He has made due with minimal income and lost years of his life to misery and poverty unnecessarily.

The moral of the story is that it’s better to be right than wrong. No surprise there. The market rewards those who predict the future correctly, which is why markets are the best place to look to get the most accurate possible predictions about the future. Markets today are predicting that oil prices five years hence will be about the same as today. That’s the smart way to bet.

Hal- the markets five years ago did not predict the price today. option prices for tech stocks didn’t show a drastic fall on jan 1 2000.

a few oil tidbits:

non-opec production is is estimated to grow more than worldwide demand will grow in ’07.

opec believes that a price much above $70 encourages replacement or alternative energy.

russia taxes almost every dollar of oil price above $30 so there is no profit incentive to drill as the price rises.

hugo chavez has continued to replace trained oil workers with political cronies since taking office and his production has fallen every year (offset by rising prices lately).

a lot of the peak oil apostles claim we know where most of the large oil fields are and they are past peak production but we find new ones somtimes. how fast we can find them will be the key to the where the peak is and replacements for oil will determine how rapid prices rise if and when demand grows faster than supply

I like Max’s definition of “Peak Oil” = The year we will have maximum flow (max production) of oil.

So, using that definition, then here’s a clarification thought to Hal —

Peak oil doesn’t say anything about who is smarter: Cornucopia Charlie or Domsday Dave (CC or DD).

If for example Peak Oil is Today, then what might happen is that everybody gets wise to this fact, and internalizes it. The government raises taxes, and offers Alternative Energy Subsidies. Consumption drops within two years, and DD is screwed and CC did the smart thing, even though he was wrong about Peak Oil.

There are many scenarios where CC “wins”. Other scenarios are: We solve the technical problems with fusion enregy OR There is a very long recession (perhaps WW3?).

On the other hand there are Peak Oil scenarios where DD “wins” even though he is wrong on the facts: Imagine a case where we discover that Antarctica floats on oil, more oil that all currently known reserves. In response to this discovery all coal and nuclear power plants are closed and all conservation stops. New oil flows from United Antarctica Oil Company, but our ability to consume energy is essentially unlimited, (Just like our ability to fill up all freeways with more cars), so we ramp up consumption faster than production — Now there comes a decade where oil prices rises steeply, until price elasticity brings it in line with production, AND DD makes a mint, cause he has spare oil to pump — He’s wrong about Peak Oil but still makes out like a bandit.

So – Peak Oil is true, but it doesn’t say much about how to invest or how the price of oil will go.

Just look at the price of whale oil – the wave of the future in 1880. We Peaked that Oil a long time ago, but it didn’t have much effect on energy prices, because we discovered cheaper energy sources.

Lets say the price of oil did increase past $100 per barrel. The economy would slow demand and the price would drop. Also increased investment would result. Remember, most oil/gas reservoirs only recover about 30% of the oil/gas in place – 70% is left to recover given a higher price.

40 years ago, it took one barrel of oil to produce 30 barrels. Now, 1 barrel produces 5.The Alberta oil sands; one barrel produces less than 3. When it goes 1 to 1, the lights go out.

One interesting question is whether in the long run there is any hope for replacing oil with other sources of energy. Some people argue that oil is such a concentrated energy source that nothing on the horizon can equal it.

This is not true, however. Nuclear energy is much more concentrated than oil. In principle, we could convert to a uranium economy. It would be necessary to use plutonium breeder reactors in order to make the uranium last. This has many problems but it shows the falsehood of the claim that oil is the last and most concentrated energy source we will have available.

Another possibility allowed by the laws of physics is nuclear fusion. This will create virtually inexhaustible energy from sea water. Again there are many practical problems to overcome but it further shows that there are no scientific grounds to claim that oil is irreplacable.

A simple and prosaic example is coal. The world’s coal resources are considerably larger than oil and can allow continued use of fossil fuel for many more decades. Yes, steps have to be taken to deal with CO2 emissions, but that will be necessary anyway. Even today’s CO2 levels are higher than have been seen for millions of years, during which times sea levels were far higher and most of Florida was under water. We need to develop technology to cool the earth and/or remove CO2 from the atmosphere. Given that technology, coal will be a very practical energy source for decades to come.

And a final example is simple solar energy. This is coming down in price rapidly and almost every day we read about new projects and technologies that are making solar electricity ever more competitive and practical. The United States receives enough solar energy just on its rooftops and pavement to more than supply its energy needs, and I imagine that is the case for most of the world. The total solar energy received worldwide is vastly greater than any reasonable extrapolation of our energy needs over this whole century.

There are many possible energy sources which can take the place of oil. None of them are trivial to develop, but then, an oil refinery would have seemed unimaginably complex just a century earlier. With our improved technological base there is no good reason to claim that oil is the only energy source that can fuel continued economic growth. Our current scientific knowledge leaves open many alternatives to oil that can provide far more energy and provide for human needs for the foreseeable future.

good point, because the dreamers kept saying that as technology improved, drilling and production would become more efficient. not happening.

Ed, I think that if you take the time to research it, you will find the exploration, production, refining technologies have very greatly improved, something anyone in the industry is well aware of.

—

‘peak oil’ is a cute theory and certainly has sold books but to extrapolate from one level, local, to another, global, is erroneous.

No one, no individual, no company, no institution, knows total ultimately recoverable reserves of crude oil. There seems some assumption that the planet has been entirely explored and at the most modern level. It has not. There seems some assumption that technology must do what it has not done, become static.

Neoclassic efficient market theories of price formation have not, and do not, apply. Still more the case when price has, over the last roughly two decades, become increasingly determined through speculation in paper barrels.

Someone above seems to believe that the recent decline results from spec – but, to a great degree, so did the rise. It is not a case of fundamentals driving the upside and spec the contrary.

Amazed, I never said that technology hasn’t improved greatly. Of course it has, and in spite of that, the EROEI [energy returned on energy invested] has not improved.

Lets say the price of oil did increase past $100 per barrel. The economy would slow demand and the price would drop.

Production would also drop – further slowing the economy until recovery was possible (re-stimulated by the low oil price) until yet again supply constraints were breached resulted in high prices and economic downturn.

Also increased investment would result.

Most conventional oil – the sort that fostered the massive post-war expansion of the world economy was found way back when it was worth just cents on the barrel. Then the oil just oozed out of the ground and the big fields were quickly found because they were so profitable too find. New discoveries are down 70%+ from the discovery peak in the mid 1960’s and the size of fields being found are now much smaller. Nowadays we are consuming 3 or 4 barrels of old oil for every new barrel found. No amount of money has been able to turn this situation around although technology has been able to mitigate the decline through the application of secondary oil recovery methods and other techniques. Nevertheless the trend is still one way – down. Today most new “oil plays” are to be found in deepwater, in remote and/or unsafe areas, and in Canadian tar sands mining operations, all of which require big investments and a high oil price to ensure feasibility – some as high as $50 per barrel. Any really significant decrease in the price of crude would make many of these projects economically unviable now and in the future. In which case, production would fall further.

Remember, most oil/gas reservoirs only recover about 30% of the oil/gas in place – 70% is left to recover given a higher price.

Most oil is never recovered because of geological constraints. Enhanced oil recovery (tertiary recovery), where economically feasible, does not produce significantly more oil (5-15%). Where it does so, it is at a very high price. Remember peak oil is as much about the end of cheap oil as it is about a production peak.

Supply, production and the margin between this and demand are at all time highs…

So OPEC wants to cut production again because PRICES are falling…

kinda easy for anyone with their head on straight to see whats been driving oil prices.

Its amusing, but very sad to see the peak oil fanatics come out of their caves like rabid little trolls to defend this delusional, theoretical and patently unprovable urban myth.

its worse than watching trekkies at a Star Trek convention or a pack of X-file groupies..

I just wonder, do any of these defenders of the holy “peak oil” grail THEORY, get compensated for their valiant and misguided kamikaze efforts??

…considering the profits they have helped generate over the last 5 years for oil producing nations, whats left of the Seven Sisters and their stockholders.

If this pack of snake oil salesmen, corporate dupes and hacks does not own EXXON/Mobil stock, they should at a minimum, be put on the payroll for their campaign of FUD. (fear, uncertainty and doubt)

A sterling example of brainwashing, propaganda and the dichotomy between conscience and authority that has ruined this country.

You should investigate two areas to help your analysis.

1. What is the impact of the cartel (OPEC) and what is the expectation of future impact?

2. What have 5 year futures done over time? They will have volatility of course. But will not have Katrina-like changes. They better reflect the market’s evolving view of the same thing that you are trying to noodle out.

“For example, the announced intention of OPEC producers to cut back production as the price goes below $60 might be most naturally interpreted from that perspective– producers don’t see it as being in their interests to sell for less, given what the oil will be worth in the future.”

This reflects a fundamental econ cluelessness. The OPEC action is almost certainly an attempt to influence price by cartel action. Not a rational guess versus the markets. A rational actor would assume that the markets are efficient and that others can store the oil nearly as easily as they can.