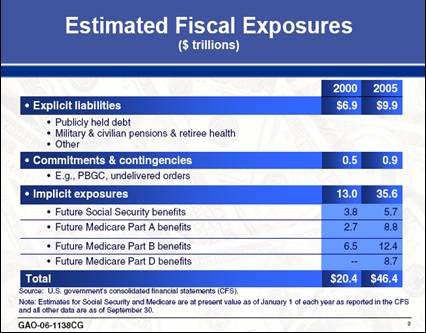

In present value terms, where were we in 2000? Where are we now?

Things are looking pretty dire, according to the GAO’s Comptroller David Walker.

Figure 1: David Walker, “Saving Our Future Requires Tough Choices Today,” Speech at UT, Austin, September, 28, 2006.

When the President speaks of the Administration’s commitment to fiscal restraint, and the need to rein in Social Security, it behooves us all to look at the fourth line under “implicit exposures”; the largest single increment to the the present value of liabilities — larger than explicit liabilities (U.S. Treasury debt) run up with all the budget deficits over the past 5 years, and larger than Social Security liabilities that have troubled the Administration — is Medicare Part D, passed by this Congress, and signed into law by President Bush.

Wasn’t there any oversight at this time? And didn’t somebody know about the immense fiscal burden imposed by the passage of this legislation. The answers are respectively “no” and “yes”. As detailed in “Medicare actuary details threats over estimates,” Government Executive, March 24, 2004, the information was suppressed until after the passage of the bill.

In testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee, Foster for the first time discussed publicly how Thomas Scully, the former director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), threatened to fire him if he responded to requests by members of Congress seeking cost estimates of the Medicare bill that Congress passed last year.

The Congressional Budget Office had estimated the new law would cost $395 billion, while Foster’s tally was $534 billion. Many conservatives resisted the bill, and others were only convinced to support it by promises that it would not top $400 billion.

House Ways and Means ranking member Charles Rangel, D-N.Y., said if Foster’s estimate had been made public, the bill would have died. “You would not have had the votes to pass this if the cost of the bill was known,” he said. As the bill was being crafted, Foster said his estimated price tag fluctuated but remained between $500 billion and $600 billion.

Foster said he reminded Scully of conference report language in the 1997 Budget Act that established the Medicare actuary as an independent office given the task of providing Congress with “prompt, impartial … information.”

But Scully dismissed that language in “unprintable” terms, Foster said. “The polite version was that the conference report meant nothing,” he added.

After consulting an HHS lawyer who advised him that Scully did have the authority to prevent him from sharing his analyses, Foster said he determined to remain at the agency despite what he thought were Scully’s “inappropriate … unethical” demands.

See also the Inspector General’s memo. Concerns about criminality were raised by the Congressional Research Service

What ever happened to Thomas Scully, the former director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services? From Bestwire

Fourteen days after Congress passed the new Medicare law in December, Scully left CMS to work for a law firm that represents hospitals, drug companies and other corporations with millions at stake in the Medicare program he helped shape. There was also a minor controversy centering on the fact he was actively job-hunting with a firm whose financial fortunes were directly affected by the decisions he made as CMS administrator.

Technorati Tags: budget deficits, fiscal exposure,

Social Security,

Medicare Part D,

Thomas Scully, and

Medicare Actuary.

This is mostly well-taken, but I suggest that it is misleading in two respects. The changes in Social Security and Medicare Parts A & B are not due to policy changes between 2000 and 2005, but to moving the ’00 levels up in terms of present value.

Second, a business firm might have an outstanding debt that could be called by the lender, but there is no analogy to the Feds. The numbers shown reflect an accumulation of discounted annual pay-outs over an extended period of time, usually either 75 years or over an infinite horizon. So the use of the word “exposure” is open to question as alarmist rhetoric.

It is also worth mentioning that Scully was a lobbyist for the Federation of American Hospitals prior to getting his Medicare job in 2001. He was a medical lobbyist, spent a little over two years doing his dirty deeds in government, then back to being a medical lobbyist. I think it’s less a revolving door than a freeway with a short rest stop for corruption.

The bigger & more grandiose the government gets, the greater the probability & extent of corruption.

Still you always step on the cockroach you see: In other words, good of you to shine the light on this one.

Miracle Max: Yes, you are right, the upward revisions to items in the first three lines under “implicit exposures” are not due to primarily to policy changes, while the fourth line (Medicare Part D) is.

On the other hand, while the USG differs from private firms in that these exposures can’t be called in like debt, it is true that in the future, if taxes do not rise to cover the expenditures, then either cuts must be made to the transfer programs, or increased borrowing by the USG must occur. To the extent that the private sector might be willing to lend at only much higher rates, these are “exposures” of a sort.

Menzie, do you happen to know how government debt held by the Federal Reserve banks is accounted? Is it considered “debt held by the public”?

(It doesn’t change the picture you paint materially, but if Fed holdings are included in the public debt, “explicit liabilities” are overstated by ~0.8 trillion, as the stock of Fed-held securities tends to grow over time, and the Treasury faces no net servicing costs on this debt.)

Thanks for this clarifying, if depressing, post. An estimated “exposure” of $46.4T represents ~3.5 times US GDP, which is worth remembering th next time someone points out that US debt to GDP is moderate and manageable.

Libert d’expression et intrt gnral

In France many public servants had their blog closed (in french)

Menzie,

I do agree with you one this one. There are other considerations such as more market based pharmaceuticals and the coordination with the HSAs, but that is almost wishful thinking.

The only real positive that I can find in Medicare Part D is that it will hasten the financial problems and force a solution sooner rather than later, but this is much like saying we should allow doctors to return to bleeding patient so that they become chronic faster.

I do believe this needs much more economic analysis and exposure than it has been getting from both sides of the aisle.

What angers me about this Medicare Part D issue is that the President and his allies will in the same paragraph promise to keep taxes low and brag about handed out these free goodies. When I listened to folks like Bob Graham back in 2001, what I heard was a leaner program financed by tax increases. And oh yea – Bob Graham voted against that 2001 tax “cut” (deferral). Incidentally, Mr. Walker’s numbers in my view understate the problem by not including what is a reasonable expectation of other spending and taxes under current policy. But hey – why suggests that the present value of future deficits is likely twice his figure as we wouldn’t want to scare voters before the election. Would we?

If something can’t go on, it will stop. Medicare in its present form is clearly doomed to an early demise. I doubt that anyone now under 50 will ever see the benefits that seniors now take for granted.

As the costs to the Government mount, it will either cut benefits, or move to a Canadian style single-payer system to drive waste and profit out of the system. Since the first is a guaranteed ticket to electoral defeat, I expect the latter to be tried first.

If something can’t go on, it will stop.

Another possibility is that taxes are raised to a level sufficient to support current Medicare and hopefully, Medicare for all. It works in most of the industrialized world.

Anyone who thinks the nation’s fundamental fiscal situation results mostly, or largely, from events of recent years should take a look at GAO’s projections circa 2000, such as at http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d01385t.pdf

With surpluses then projected to run for years yet, no Bush tax cuts, no recession, no 9/11, no war or increase in the military budget, no Medicare part D etc., projections stop mid-way through the 75-year look-ahead period because annual deficits hit 20% of GDP and are compounding straight up, and the continuation of government from there is “implausible”.

IOW, there’s absolutely nothing either new or secret about the substantive state of the government’s long-term finances. Politicians just ignore it — that’s *one* thing they agree to be bi-partisan about, since Republicans could hardly peddle tax cuts if they admitted this situation, and Democrats could hardly peddle the idea that entitlements (let’s add nationalized health care!) are no problem.

This process of politicians buying votes now with promises for which the bill will arrive on some later generation’s watch is systemic, bi-partisan, inherent in the political system.

Look at FDR’s original Social Security Act — he *insisted* that it provide a fiscally sound and sustainable return of the federal bond rate to each cohort of particiapants as a group, not pay off one generation at the cost of another, and build up a substantial saved surplus 50 years ahead into the 1980s.

That lasted all the way until 1939, when the original Social Security surplus came pouring in.

Then the liberals and conservatives in Congress agreed in unision that the surplus, originally meant to build up national savings by redeeming the debt, should instead be divied up half through tax cuts and half through spending increases, wiping out the surplus and turning Social Security paygo.

The first head of Social Security, Arthur Altmeyer, went to the leaders of Congress protesting that this would inevitably wreck SS’s long-term finances and drop a large unfair cost on future generations — and came back saying the leaders told him: “So what? We’ll be long gone.”

Sure enough, by the early 1980s SS was broke and had to be bailed out via classic Congressional compromise — 50% tax increases, 50% benefit cuts, the great majority of both landing on the as yet non-voting young. With the result of that being today’s young will get $10 trillion less back from SS than they contribute, compared to the $10 trillion more earlier generations got (which surely will have a corresponding effect on SS’s future political popularity). And the leaders who created that situation were indeed long gone.

The same thing is going to happen to Medicare, of which Part D, as terrible as it is, is only a smallish part, on a hugely larger scale — and to SS’s own now approaching new deficit, of course.

“So what? We’ll be long gone.” It’s the same incentive politicians everywhere around the world in developed countries have responded to for the last 60 years or so, party politics anywhere having precious little to do with it. Just look around.

It’s been one of the costs of democracy.