Caclulated Risk had some interesting observations this week about why forecasts for housing differ so widely across analysts.

CR wrote:

During the housing boom, there were two distinct views of the causes of the boom. The consensus view was that the boom was mostly driven by fundamentals and perhaps a little “froth” in 2005.

The minority opinion was that the housing market had become a bubble. The minority view was based on evidence of speculation: flippers, a high percentage of investment purchases, and homebuyers using excessive leverage, especially with nontraditional mortgage products.

Now that the housing bust is here, there are also two views of the bust. The consensus view is that the “worst is over”. The minority view is that the bust has a ways to go.

Not surprisingly, those that felt the boom was based on fundamentals now believe the worst is over. And those that felt the boom was driven by excessive speculation believe the housing market will continue to slowdown. How one viewed the housing boom colors how one looks at the housing bust.

I would define a bubble as a price appreciation that is driven not by fundamentals but instead by the pure expectation of future price appreciation. One of the difficulties I had with the bubble story was that the extent of house price appreciation differed so much across different communities. The graph below shows the state-by-state 5-year housing price appreciation between 2001:Q1 and 2005:Q1. Did house prices in California, Nevada, and Florida go up so much faster than in Ohio, Tennessee, or Indiana just because people nearer the oceans expected more price appreciation? Or was it instead related to the fact that the “bubbly” communities were the ones where population and the number of people trying to buy a home were growing most quickly?

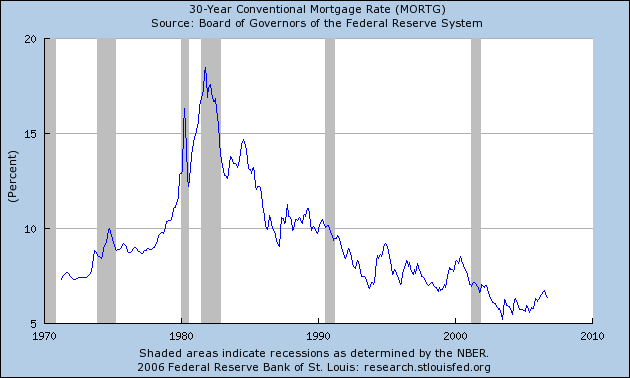

To be sure, there was also an aggregate component to the national house price appreciation that had very little to do with the growth of the aggregate U.S. population. But this could easily be attributed to the very low interest rates over this period:

|

You can of course try to model what the correct price response to local fundamentals should be. But no matter how carefully you build those models, there will always be something you have left out. An old paper of mine shows that the response of the market to those factors you’ve left out– for example, the response of the market price to an unobserved anticipation of future local population growth– would look exactly the same in terms of observable data as would a speculative price bubble.

If it is indeed the case that low interest rates were a key factor in the housing boom and that rising interest rates have now been the key factor responsible for the housing downturn, it seems logical to me to expect that the decline in mortgage rates since this summer might begin to reverse the housing slide. As of two weeks ago, there certainly were some hints consistent with that possibility: pending home sales up in August, recovery of stock equity prices (particularly for homebuilders), uptick of housing starts and new home sales in September, and decrease in months’ inventory of unsold new and existing homes. However, the October housing starts and permits numbers provided quite a nasty jolt to that happy story.

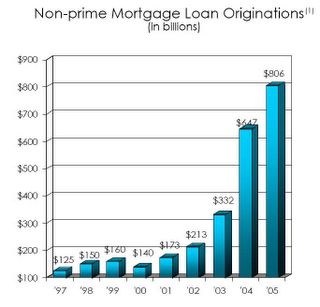

Even without the troubling October figures, and even if one takes a fundamentals view of recent developments, it is hard not to share CR’s concern about the explosion of unconventional mortgages. Low interest rates were presumably one factor behind this. But any neoclassical economist would naturally be concerned about the possibility that some kind of market failure or perceived government guarantees may have prevented the risk from being accurately priced. Moreover, to the extent it is the case, as CR observes, that even the conventional wisdom had acknowledged a “little frothiness” in some markets by 2005, the change from expectations of price appreciation to price depreciation could itself have a significant impact on the market.

|

One thing I’m sure of– both CR and I will be watching this week’s home sales figures with great interest.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

housing,

bubbles

Yes, housing mortgage rates were at historically low rates, and supply restrictions in certain rapidly growing states certainly contributed to some of the frothiest price increases. But Robert Shiller in the second edition of his Irrational Exuberance last year fairly conclusively showed that such fundamental ratios as price to income and price to rent were at all time highs in 2005 nationwide. Also, the rate of increase in 2001-2005 was only matched by 1946-1950, the latter clearly exhibiting a much greater supply-demand adjustment to imbalance. That there were so many of the unconventional mortgages is exactly the sign that even with the low mortgage rates people needed something extra in order to afford to buy, given the off-the-charts price to income and rent ratios.

Rates? While you may be right on the fundamentals, I believe the evidence suggests you are wrong on rates.

You can either read Fisher and Quayyum (PDF), who agree with you that housing prices mostly have been driven by fundamentals, but whose first major finding is, “the housing boom has not been driven by unusually loose monetary policy.” Or, you could look at the homeowner financial-obligations ratio and note that mortgage payments are at historic highs. Either way, whatever is going on, I don’t think low rates do the trick in explaining things.

As for the market price, preposterously generous tax breaks on owner-occupied housing may have something to do with it. Still, I have yet to see a convincing argument that current prices are market-clearing with extremely high vacancy rates.

I can absolutely see arguments that there was no bubble in the traditional sense. However, I find it hard to believe prices will continue to rise at a 5% real rate, the way they have for the last decade. Merely returning to 1% real annual appreciation will act as a drag on production for a while.

“Did house prices in California, Nevada, and Florida go up so much faster than in Ohio, Tennessee, or Indiana just because people nearer the oceans expected more price appreciation? Or was it instead related to the fact that the “bubbly” communities were the ones where population and the number of people trying to buy a home were growing most quickly?”

The answer is: http://piggington.com/love_of_god_vs_love_of_money

Just tongue in cheek, sort of. But, there’s some truth to it, I think.

Keep up the good work, Professor.

I do wish that housing comments would distinguish between housing starts and housing prices. As it is we see data on housing starts supposedly contributing to a discussion about house price appreciation.

Did the decline in nominal interest rates in the USA over the 15 years leading up to 2005 cause asset prices in general and housing prices in particular to increase? Surely we should be able to come to a consensus view on such a simple question

That’s an amazing graph, pg.

Sorry to be unclear, Anonymous. In my mind the focus of the discussion was on whether the quantity of houses sold has bottomed out, my goal being to reflect on CR’s perspective as to why it has not. But on re-reading the post, I can see how someone might have thought the focus was entirely on the price, in which case there would indeed be a bit of diversionary material here.

The fall in the 30 year mortgage rates since the early 1980s appears to be a strong argument justifying the rise in housing prices. But should prices & quantity of sales be driven by nominal rates or real rates?

Based on my understanding, real rates should drive the housing market and as real rates are not exceptionally low (unlike nominal rates which are at their lowest in 35 years) it is difficult to justify high house prices.

I did speak to a U.C. Berkeley economics professor about this and he said that bank lending uses nominal rates to define credit constraints for example “current debt burden” to income ratio which may explain the high housing prices.

So is it nominal rates or real rates that drive the housing market?

Gavin and Anonymous,

Although there are arguments for why the nominal rates themselves could be a factor (e.g., tax-deductibility of nominal interest expenses in the case of equity evaluation, front-end loading in the case of home mortgages), to a first approximation it would be the real rather than the nominal rate that matters. I plotted the nominal rate here simply because it is less clear how to form a real rate. Unquestionably both real and nominal rates were quite low in 2002-2003.

Thanks for clarifying your position on interest rates and house prices professor.

One of the best studies on house prices I have seen is by Andrew Farlow at the University of Oxford. See the link below.

http://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/members/andrew.farlow/

Unlike most others who look at the topic, he also includes behavioral economics factors in addition to the traditional explanations such as low interest rates (nominal or real).

‘Or was it instead related to the fact that the “bubbly” communities were the ones where population and the number of people trying to buy a home were growing most quickly?’

Can’t be just that, considering that the house prices in North Carolina and Texas, two fast-growing states in population, hardly increased at all either. Of course, both have fairly pro-growth policies and light zoning and other regulations, and their major cities aren’t located next to oceans, which may help.

In your post you fail to mention real interest rates, and then in your reply to Gavin you attempt to justify yourself by arguing that it is less clear how to form a real rate. For decades I and many economists working on inflationary environments have followed Irving Fisher in just substracting any approximation to the inflation rate from some nominal rate; whatever the measuremente error may be, most likely is not different from the error caused by IPC’s inflationary bias. You must be quite young to forget about how low real interest rates were before 1980 and how erratic they were in the 1980s. Whatever tax or credit reason you may have to take nominal rates into accont, it does not justify to ignore real rates in an analysis that pretends to explain an asset price over a long period of time. To say just that both rates were quite low in 2002-03 is irrelevant.

In addition, in your post you say that “rising interest rates must now be the key factor responsible for the housing downturn”. Again, tell me what has been happening with real interest rates before jumping to such a conclusion. If you want to explain the downturn, perhaps you should focus on monetary policy (by the way it looks like Bernanke may now lower nominal rates to make up for his previous mistakes–you may honor Milton with a discussion of who pays for Fed’s mistakes).

I suggest that when you draw your graphs, if it is possible you should have the axis be at the zero point. It makes the graph more understandable and puts the changes into perspective and proportion. Two of your graphs are almost at zero and could easily have gone all the way there.

Edgardo:

The link I posted to the web page for “Andrew Farlow” looks at both nominal and real interest rates for the United Kingdom. He also looks at several other factors.

I was looking for similar analysis on the U.S. housing market, especially California.

I would define a bubble as the short-term consumption of long-term economic stimulus.

Will the consumption of housing in the last several years detract from housing activity going forward? I would say YES for two reasons.

1. Many fringe buyers got into the housing market through high-risk, unconventional loans. As foreclosures from these loans begin to mount, banks will tighten their lending standards.

2. The “speculative” forces work in both directions. The deflation of home prices will cause (is causing) home buyers to wait. This will create a doughnut hole where for the next several years, the housing market will remain below its long-term potential.

Did house prices in California, Nevada, and Florida go up so much faster than in Ohio, Tennessee, or Indiana just because people nearer the oceans expected more price appreciation? Or was it instead related to the fact that the “bubbly” communities were the ones where population and the number of people trying to buy a home were growing most quickly?

These explanations are not mutually exclusive. It seems plausible to me that areas where fundamentals lead to strong price growth would also be the areas where owners and potential owners would be most excited about that price growth, and, after it had continued for a while, be most likely to come to rely on its continuance (thus sparking a speculative bubble from what had initially been fundemental-based price appreciation).

MD, one of the bubbliest (yet usually overlooked) states regarding housing, saw a net decrease (PDF) in population from net outmigration in both 2004 and 2005, yet prices are up over 100% since 2000. Even with the so-called “DC effect” of coming north to Balto. and the surrounding area, still more people moved away than came. Yet prices in the metro area doubled in 5 years…not based on fundamentals, but all speculation.

Nikki,

I do have to point out that you contradict yourself with the link that you provided. It clearly states in the first sentence that Maryland saw a net increase in population of, if memory serves 37,000. Yes, net domestic migration was negative (as it is in many high priced areas, such as LA, SF Bay), but overall population growth was positive. Another explanation is the “Superstar Cities”, explained in this

paper

Make of it what you will…

I am an engineer, not an cconomist. But there are a number of reasons why I think Hamilton’s reasoning is flawed.

Firstly, while interest rate reduction makes the monthly payments more affordable, there is plenty of evidence–both anecdotal and statistical–that a large number of people who could not afford homes even at the reduced rates bought homes after taking advantage of loose credit standards and ARM.

Secondly, looking at the charts of prices for local markets like Northern Virginia, there was a sudden surge in prices in early to mid 2004 by as musch as 20% in 3 months even though rates didn’t change much within those three months.

Why is it hard for Hamilton to accept the simple truth that it was simply market psychology–people with short memories assuming prices always go up–that was the major reason for this bubble? Of course, low interest rates were a factor in that it affected psychology about affordability, but interest rates in themselves cannot explain the bubble.

And what does Hamilton say about today’s report that median prices of existing homes fell 3.5% year-over-year?

Nathan,

You’ll note that most of that very small growth over that time is due to the birth/death ration and a small contribution from “international migration”. However, babies do not buy houses, and the point is that the population growth of people moving into the state who would purchase a home was far outstripped by the number of transactions taking place, and therefore was not based on market fundamentals.

TKuga,

If it is market psychology what was the difference in psychological conditions that created the surge in prices?

Nikki,

Well, who can predict or control the thoughts of individuals –the same person who was thinking that this was a bubble and prices would fall might be persuaded by talk from friends, neighbors and real estate agents that real estate prices always go up. That creates a rush where people feel if they don?t buy now they will be priced out of the area forever. Because nobody can say how many people will rush in and how many people will change their minds, there is always an ebb and flow, which can result in sudden surge for which no fundamental rational reason can be given. So that answers your question?there is no need to have a change in ?psychological conditions? for the surge. It is the very nature of psychology.

I saw this dynamic in the greater DC area, including Northern Virginia. Some of my friends who bought in 2005 at the peak of the market feared they would be priced out, but in the end they had to leave the area this summer and after waiting for several months to sell without any success, they sold recently at significant losses.

Keep in mind people always want to buy houses. I mean there has always been high demand for homes. Pre-1998, that didn?t translate into a bubble because credit standards were tight and so people?s idea of affordability was different then.

Even taking into account other reasons like population growth, job growth, zoning restrictions, immigration, etc., price rise was so disproportionate to the growth in these factors. But the public was told that because of these factors, there would be no property left for them to buy. Already, the glut of properties in the market and falling or flat prices, have proved the invalidity of such ?fundamental? explanations.

When there are manias affecting huge populations, until a certain tipping point is reached, it will go on and look like something has ?fundamentally? changed. Then there are economists who try to explain that ?fundamental? change and cheer leaders including Greenspan who cheer it on.

It is highly irrational to think that there will be no consequences for such manias and that house prices will resume their upward march. But some people persist in it anyway.

My name is Sean Olender and I’ve been expecting a housing bust since 2002. The shift to lax lending and mind boggling repayment terms 2003 to 2006 surprised me and prolonged the boom longer than I imagined.

Clients come to my office with incomes of $45K to $60K who have taken $600K or $700K interest only ARM mortgages to buy houses with ZERO down. A guy was in last week who was 22 and worked in construction with an income of $45K and a $700K neg am mortgage on a house he closed on 11/2006. These loan to income ratios are unbelievable. I wouldn’t be so amazed if it was one person, or three. But it’s almost every person who walks into my office. The most disturbing part is none of them understands any of their loan terms — not even the interest rate. They only know their monthly payment and they don’t know it will change in the future. They don’t believe me when I point out the terms in their own loan after they bring in their papers.

But the one thing that informed me for sure the boom was over and the downturn had begun was when a friend of mine bought a condo in a suburb of St. Paul. This friend is partly supported by parents and probably works 20 hours a week.

Bubbles in any asset (stocks, bonds, real estate, beanie babies, etc.) are defined by price increases as outsiders pile in to buy the asset. People on the outside see and hear about the money being made and want some of the action. The increased demand results in a self fulfilling prophecy that drives up prices. Eventually there are no ‘greater fools’ to pile in and at that moment the market shifts. It’s like musical chairs when the music stops.

Asset bubbles function like a Ponzi scheme but because the action isn’t controlled by a single person or group, it’s legal.

It’s been a long time waiting, but my friend signed papers in December 2005 and closed in January or February 2006. That for me is proof positive that the top was reached. I had lunch with an economist friend of mine in May 2006 and told him that the top was reached a few months earlier and he didn’t believe me. I drew a graph and he kept it. We’re having dinner tomorrow night and I expect I will be treated for my foresight because the data is bearing out my predictions at a slightly faster pace than I’d suggested at our last dinner.

Low rates aren’t going to save this. The fact that rates are near 45 year lows and the market is in free fall indicates that this is about more than rates. If rates stay low, this will be a terrible, drawn out slumping market with significant price depreciation, but probably causing only a short recession in the broader economy — perhaps two or three short recessions as we skip along the bottom of this mammoth credit bubble. But if rates should rise 1 or 2 points, the fast credit and money supply contraction from bad loans being written off might spell a depression.

And I know that all of this has started from the fact that a single person bought a single condominium. It means there’s no one left on the outside waiting to get in. No matter how loose the credit is, absent digging up corpses and giving them stated income I/O mortgages, there’s simply no one left — no ‘greater fool’ to rescue everyone who is in the market now — because I’m fairly sure that everyone is now in the market.

Having a fixed rate loan and not having to worry about foreclosure is nice, but a careful thinker will realize that it’s nicer for the bank than the borrower. If you buy a place for $161,000 and have no problems making the payments, but four years later someone buys an identical place next door for $98,000, it’s hard to feel good about being able to afford one’s mortgage payments. Not least it will make it almost impossible for a large group of people to freely move about because even if they can afford to make their mortgage payments, they won’t be able to afford to sell their houses without a deficiency judgment and the resulting credit stigma (which in my view is better than taking a $60,000 after tax hit to assets on an income of $25,000 a year).

The larger economic and social effects of this bubble will be very different than the last. This time those piling into the market weren’t day traders, investors, risk takers. This time it was EVERYBODY and that’s going to make the ride down have disturbingly broad effects on American society.