Or some (more) things in the Budget Proposal don’t add up

Suppose the President’s plan to escalate troop levels in Iraq succeeds in stabilizating Baghdad. What does that mean for future expenditures in support of the occupation of Iraq? Is the President’s $50 billion request for Iraq related expenditures in FY2009 consistent with the plan? This article from GovExec.com provides some hints.

The U.S. military is gathering its troops for a last-ditch surge to pacify Iraq.

Units from the regular force and the National Guard alike have had their tours of duty extended in Iraq to swell the force on hand. A new Pentagon policy, meanwhile, has given commanders extraordinary authority to call up Guard and Reserve troops for a second tour, or a third.

Yet at the same time, the number of Guard and Reserve troops on active duty has dropped to its lowest level since January 2003, just before the invasion of Iraq. This is no momentary dip but a long-standing trend.

The number of Guard and Reserve troops deployed to Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere worldwide has been dropping steadily since September 2005. Yet the size of the force abroad, counting regulars and citizen-soldiers combined, has consistently remained between 250,000 and 300,000. That means the burden has shifted.

….So if the Pentagon has new powers to call up reservists at the same time it is surging in Iraq, why isn’t it calling them up? The answer lies in what could happen after the surge.

Even if the extra 20,000-plus combat troops stanch the sectarian bloodletting in Baghdad, the only thing that the U.S. gets out of their success is more time. It will still need troops there, and President Bush shows no signs of pulling them out.

If the surge fails, the possibilities of anarchy, genocide, or a wider regional war require the U.S. military to have devised its own contingency plans. So, while Congress and the media may be fixated on what happens between now and August, military planners are drawing the blueprints for what comes after that.

The military claims it needs no Guard combat brigades for 2007, said John Pike, top analyst and outspoken founder of the private intelligence firm Globalsecurity.org, “but I am guessing that 2008 may be a different matter.”

…

The Reserve and Guard units will now have to squeeze the training for short-notice response into their regular schedule of one weekend a month, two active-duty weeks per year. That is a lot of new pressure.The policy also ends exemptions that allowed some citizen-soldiers to stay at home while the rest of their unit deployed. Many Reserve and Guard troops volunteer for active duty as individuals, detached from their parent unit for months at a time; others transfer from unit to unit as they move in civilian life. Under the old policy, an individual could run out his personal 24-month deployment clock before his unit as a whole even got the call to mobilize, which meant the unit had to find a replacement for him when it was called up — a laborious, disruptive, bureaucratic shuffle.

Now, although the time required on active duty has been halved to just 12 months, the limit will apply only to a unit as a whole, not to individuals: No matter how many months a citizen-soldier has already served as an individual volunteer while detached from a unit, he or she will still have to deploy with it for the full unit tour.

“People who have gone before and maybe done pretty close to 24 months can [now] figure it’s not a matter of ‘if’ they’re going to be tapped to go back, but ‘when,’ ” Goheen said. “But most people thought that was inevitable anyway.” So although no full brigades of National Guard combat troops are on the deployment schedule for 2007, Goheen went on, “our units will be needed again. The hope was they wouldn’t be needed until ’09. Unofficially, there have been reports it could be ’08.”

Whether the surge succeeds or not, the Guard and Reserves are treating 2007 as their chance to regroup for the long haul, not as the last year of the war.

The fact that the President’s budget allocates only $50 billion to FY 2009 and yet the DoD is readying the National Guard for further deployments suggests a bit of of 2+2=3 math. (Of course, it could be that everything is consistent; it’s difficult for anybody to tell because of the lack in transparency in DoD budgeting; see the CSBA assessment).

Of course $50 billion in FY2009 is consistent with an end to the Iraqi occupation, and redeployment of U.S. forces to surrounding regions. But this would not necessarily mean that the total defense budget numbers added up. From Sunday’s New York Times article “Iraq’s Fading Grip on American Business”:

In the United States, the most direct economic effect of the war is on the federal budget, which has added hundreds of billions of dollars in military and reconstruction spending in the last few years. According to basic economic theory, that extra spending should stimulate the economy by creating new demand for goods and services.

But the situation isn’t that simple. It’s possible that money spent on the war could have been used for more productive investments instead — scientific research, for example. The net effect of the war, in that case, would have been to hinder economic growth. And while military spending might be stimulative, it might also be pushing up interest rates by increasing the government’s borrowing, as well as raising the nation’s eventual need for taxes to repay those debts.

If the economic effect of the extra spending has been unclear, there is also no guarantee that military spending would fall if the troops came home. David R. Scruggs, a senior fellow in defense industrial initiatives at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, says the Army is in urgent need of repairs and refitting for its equipment, especially armored vehicles. Those costs will eventually have to be paid.

“We’ve got some historically high rates of inoperable vehicles right now, and battle damage is only part of it,” Mr. Scruggs said. “We’ve underfunded the depots and the industry to fix this stuff. It may seem improbable given the amount of money we’ve been spending in the last few years, but the money hasn’t gone into fixing old stuff. It’s gone into fighting the war and buying new stuff. We’re not going to have the new stuff for several years, and we need to fix the old stuff so that in the interim, we’ll have something.”

Mr. Scruggs also said that in a comparison with earlier large-scale engagements, the share of spending going into salaries, food and amenities for the troops in Iraq was substantially higher — and that many of those costs would continue even if the troops came home. The all-volunteer Army, now fighting a prolonged conflict for the first time, is more expensive than a conscripted one, he said; today’s force has to compete with other professions to recruit workers, and it’s also seeking out highly skilled and highly educated soldiers.

For a more detailed look at, for instance, the Reset costs associated with bringing the National Guard up to levels capable with self-defined missions, see this recent GAO report:

Without analytically based equipment requirements for the National Guard’s domestic missions to compare against the National Guard’s current inventory of available equipment, we could not determine the extent to which nondeployed National Guard forces have the equipment they need to perform their full range of domestic missions. However, we collected and examined information from two sources—the National Guard Bureau’s Joint Capabilities Database and an Army National Guard equipment inventory—as rough substitute measures of the adequacy of National Guard equipping for domestic missions. To supplement this information, we visited four states-California, Florida, New Jersey, and West Virginia—and discussed the capabilities, including equipment, that would be available within the states for their typical missions as well as large-scale, multistate events.

Our analysis indicated that the majority of states report having the National Guard capabilities they need to respond to typical state missions; however, some states and territories report capability shortfalls in one or more areas.21 As of July 2006, 34 of the 54 states and territories (63 percent) reported having adequate amounts of all 10 core domestic mission capabilities for responding to typical state missions.22 Of the 20 states and territories (37 percent) that reported an inadequate capability, 13 reported being inadequate in only one capability, and 4 reported being inadequate in two capabilities. Table 3 shows the number and percentage of states and territories reporting either adequate or inadequate for each of the National Guard Bureau’s core domestic mission capabilities. Aviation; engineering; and chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive capabilities were most frequently reported by state National Guards as being inadequate for responding to typical state missions. Most states and territories that rated their chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and high-yield explosive capability as inadequate did so because their weapons of mass destruction civil support teams had not been certified or were in the process of being established.23 For all other capabilities, the deployment of units was the most common reason state National Guard leaders gave for rating a capability as inadequate. (pages 22-23).

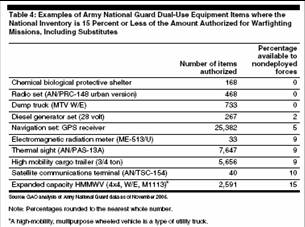

Regarding dual use equipment, the document presents an interesting table:

One has really got to wonder if the all the funding needs required for safeguarding the Nation at home will be met in the President’s budget request.

In a subsequent post, I’ll discuss the macro implications of refitting and deploying all these units when the economy is near or at full employment.

Technorati Tags: Iraq, National Guard, reserves, defense expenditures.

Check out a paper by Thomas J Woods over at Mises.

He related reearch by Seymour Melman (1917 to 2004).

He states and I agree as well as a lot of research by U Michigan that money spent in the military is parasitic and could be better used elsewhere.

That beingthe reason they won’t pay taxes to cover it and the reason the budgets are artificially rosy and low.

It is intuitive that war is wasteful.