Financial or banking panics were a recurrent theme in 19th-century U.S. economic history.

Episodes such as the Panic of 1857, Panic of 1873, Panic of 1893, Panic of 1896, and Panic of 1907 were marked by a sudden rise in short-term interest rates and an increase in the yield spread between safe and risky assets, as borrowers scrambled to find a source for short-term loans and depositors tried to get their money back from banks. These episodes were invariably followed by significant economic downturns.

|

There are two factors that could make some institutions a poor credit risk in such circumstances. The first is solvency problems– if the value of gross assets of a bank is less than its liabilities, there is no way for creditors to get all their money back. In this case, the sooner you get your deposits out of the bank, the better off you will be. The second issue is liquidity problems– the bank may have assets in excess of its liabilities, but trying to convert these assets into immediate cash could be very costly.

There is obviously a potential for liquidity problems, in times of financial panic, to turn into a problem of solvency. It may be that the bank’s assets, if sold in an orderly market, would exceed its liabilities, whereas if forced to sell immediately at fire sale prices, they would not. A big economic downturn will also reduce the probability that the bank will be repaid in full for its loans, further eroding the value of its assets. There is substantial unnecessary economic loss when liquidity problems are allowed to create insolvencies that would otherwise not arise.

With the establishment of the Federal Reserve in 1913, the United States obtained an institution with the power to create as much liquidity as might be needed to completely eliminate the second and most damaging element of historical financial panics. When you look in the graph above at the behavior of short-term interest rates before and after 1913, it is like comparing night and day. Certainly there have been any number of mistakes made by the Fed, biggest of which were the collapse of the money supply and bank failures in the early 1930s. But none of those episodes were characterized by the kind of extreme spike in short-term interest rates that had been such a common fact of life of the pre-Fed era.

|

One of the most recent and dramatic illustrations of the usefulness of this power went unnoticed by many Americans. Along with the loss of life and property when the World Trade Center towers collapsed on September 11, many of the financial institutions that played a key role in trades of government securities and interbank loans were wiped out or incapacitated, posing potentially huge liquidity problems. The Fed reacted with an extremely aggressive temporary creation of reserves, which prevented those liquidity disruptions from having major consequences. Americans were appropriately focused on other concerns that day. But we can thank the Fed that among those concerns was not a financial panic.

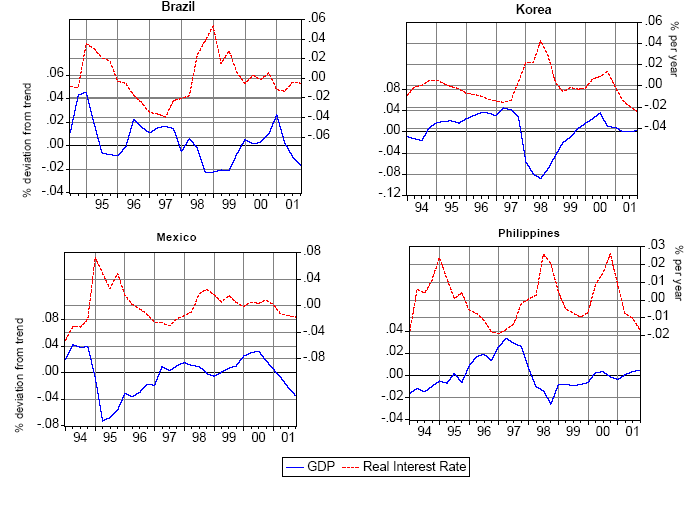

Although what was commonplace in the nineteenth century has since essentially vanished, at least as far as the United States is concerned, other countries continue to experience a closely related phenomenon, exemplified by the currency and financial crises of 1997. If you’re a smaller country like Korea for which a lot of the short-term debt is denominated in dollars, your central bank does not have the power to create extra dollars if everybody suddenly demands their payment and refuses to extend credit. Trying to flood the market with more of your own currency is just going to make the outflow of capital more severe.

|

So does this have anything to do with current concerns about subprime mortgages and interlayered hedge fund risk? I would take away two points from this discussion. First, insofar as we are talking about solvency problems, there is little the Fed is able to do to prevent those– some subprime mortgages are going to default, and that’s that. However, the Fed can and will prevent these from cascading into broader liquidity problems, by which I mean insolvencies created solely because of forced liquidation or unavailability of short-term credit. Even so, the Fed’s capacity to move aggressively on this front is potentially limited by the need to avoid a precipitous collapse in the value of the dollar. Whether the outcome would look more like the U.S. in 2001 or Korea in 1997 remains to be seen.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

financial crises,

bank panics,

Federal Reserve

JDH:

Thanks for the fascinating history lesson!

There are a number of deflationists who essentially think that the Fed insurance against panics has created a kind of moral hazard where financial institutions are able to create ever more debt, leverage piled on leverage, secure in the knowledge that the Fed will rescue them if things start to unwind. In this view, although the situation might look less volatile in the short term, it has created the seeds of an unstoppably large deflation at some point in the future (and maybe not too far in the future). It does seem to be true that total debt/GDP is at historically extremely high levels.

What would you say to such folks?

Financial Crises and Subprime Paper

Jim Hamilton at Econbrowser has an interesting post about financial crises. He delves into some economic history, comments on the role of the Federal Reserve, and offers some implications for current mortgage difficulties–all this in just a few paragr…

Professor Hamilton,

I echo Stuart’s thanks, but have a question of my own.

As a non-economist with no knowledge of how the Federal Reserve works, do you think that the institution might have a problem with scale? For example, a crisis could appear on a scale which the Fed can’t cure merely by pumping liquidity into the system?

I ask because the engine of the so-called ‘global economy’, the American housing market, seems to be running out of steam; and as a layman one can’t help wondering whether the scale of a solvency crisis generated by an outright collapse, just in terms of the sheer volume of money American homeowners have borrowed against their properties, might be too great for the Fed to manage, let alone absorb.

Professor Hamilton

Do you have any information of the role of borrowing in low yield, low interest rate currencies such as the Japanese yen on the sub prime market? Or has this been the domain of the the hedge funds? (ie yen carry trade)

I look at the top graph and don’t see anything like a single dramatic change after the establishment of the Fed. I see a steady trend towards less severe spikes and lower levels, with the panic of 1873 as the most significant end-of-era.

what i think amazes people raised in an era of more prudent lending is what i suppose greenspan meant by moral hazard?

subprime can still be lending 100% to dodgy borrowers

Alt A is very similar to subprime

Prime can still be 100% borrowing

*Only* the belief that the Fed/government will in some manner come to the rescue can possibly have created *and* still maintain such low risk scenarios for the lenders.

But as the Professor says……if the lenders are insolvent there will be no rescue. F&F come to mind and Ben mentioned them yesterday. Why were they mentioned? Is that a signal to tighten lending standards further? Prudence would suggest its needed but in a desparation scenario maybe talk is better than action?

Since this whole housing situation developed in full view of all the various authorities it suggests that things were sufficiently terrible that such a risk was deemed worth while to reinflate the economy and save what economy there was to save.

So as of now exports are at record levels and the dollar is declining and manufacturing may yet restore some balance to this picture and yet the underlying desparate nature of the thing just seems evident.

Its inflate or die.

Stuart, I think it’s a mistake to give the Fed too much credit (pun intended) for the current situation. Yes, they kept interest rates too low in 2002-2004, but I don’t see interest rates as being too low currently, nor do I see excessive gowth in the monetary aggregates. Some who advocate the view you describe point to M3, but this is not something the Fed controls. Others argue (along the lines of Anonymous above– is that DickF again?) that because people expect the Fed to mitigate risks of a liquidity crisis, that encourages them to take even more risks in other dimensions. But again I can’t see blaming the Fed for this. If you’re looking for a scapegoat, I’d point to institutions like the San Diego County Employees Retirement Association rather than the Fed.

Martin, yes, absolutely, there may be a global dimension to the current situation that is beyond the ability of the Fed to respond; for example, keeping the exchange rate stable is one of the fundamental constraints on the Fed. Perhaps we could coordinate with other major central banks. But again, all the central banks really have the power to do is address an immediate liquidity problem, and that doesn’t do anything about fundamental long-term insolvencies, if that’s what we’re talking about.

David, I don’t have a quantitative assessment of the yen-subprime link. But I will say that the strategy of borrowing yen in order to lend risky U.S. mortgages is an example of the kind of risk taking about which I’ve expressed concern. Specifically, it’s the kind of thing that can give you spectacular returns until the day it blows up.

Typically the investment results of such things as the Yen carry trade are that you get a long stream of extremely small positive returns until the whole thing blows up and you get one massive negative return that more then offsets the earlier positive returns.

thanks for this lesson. Way too many people think the world came into being full blown in 1945 and anything before that does not matter.

The Fed was created to deal with this problem and its role was to prevent these financial panics from spreading to the rest of the economy. Interestingly, in the original legislation and hearings before the Fed was established inflation control was not even considered.

Coming back to prudent lending:

No sorry it was not DickF but me:-)

The Fed is surely responsible for allowing this situation to develope. Greenspan has encouraged the idea of new paridigms at one time and innotative lending techniques at another to give the impression that the economy is expanding because of some kind of structural change rather than massive lending over which am i to believe they have no control? No control at all?

As for M2 until such time as there is an independant organisation that produces inflation data i dont think anybody believes the published inflation. Clearly if it is kept artificially low more credit can slow around without it creating, necessarily, price and wage pressures due to expectations of inflation……i think though the game is up on that one surely?

Any forcaster on the economy either has to do their own surveys of how must stuff is costing or just assume the worst and believe the data is just total junk.

In any case when house prices are rising at silly annual rates referring to official 5% inflation and other numbers without considering MEW and consumer propensity to spend like no tomorrow is just asking for trouble in a forcast surely?

Seems to me that all of this was considered and the risks were considered necessary

Sorry for getting a bit over heated!

I am just trying to figure out what is happening. If the news is good then that is fine by me…..the last few weeks have been kind of real scary. Already i see that the ABX indexs are settling down and i know a back office girl in real estate who says they had the busiest february ever for closures. The news is certainly not all doom and gloom.

News of the World #26

Use the Force, Luke! Those “Evil” Corporations, where Captain Capitalism acknowledges the grave errors of his ways. Not. Libertarianism: Past and Prospects, the new Cato Unbound lead essay, by Brian Doherty, historian of the libertarian mov…

Prfoessor Hamilton,

Thanks for your answer.

I am not sure if this is a bit off topic but what the above analysis made me think of was whether there was a propensity for a financial crisis coming out of China, India, Russia, Brazil. The Fed I am sure can deal with the domestic issues related to subprime etc and the internal imbalances within the US but now that we are in a much more interdependent global economy, where there is little central bank co-ordination I can’t help feeling there is a shock around the corner waiting to happen.

I suppose my question is: is there some parrallel between what occurred in the US during its industrialisation in the 19th century and China today and whether we could infer a likelihood of a financial crisis event in the BRIC (Brazil Russia India and China) and other emerging economies? and then assess what the knock on effects on the wider global economy might then be? (probably drastic).

JDH wrote:

Financial or banking panics were a recurrent theme in 19th-century U.S. economic history.

Episodes such as the Panic of 1857, Panic of 1873, Panic of 1893, Panic of 1896, and Panic of 1907 were marked by a sudden rise in short-term interest rates and an increase in the yield spread between safe and risky assets, as borrowers scrambled to find a source for short-term loans and depositors tried to get their money back from banks. These episodes were invariably followed by significant economic downturns.

JDH,

You imply cause and effect here between interest rates and economic downturns. I don’t buy it. It is like saying that increasing prices cause inflation. Increasing interest rates are the result of economic problems not the cause, just as prices are the result of inflation not the cause. If you look at each of the panics you will find two common causes: 1) some severe economic shock like a natural disaster or a very large financial scandal; 2) the government either trying to prevent an economic problem or trying to cure an existing economic problem.

In periods when the government (include federal reserve) did not intervene the economic problem were very quickly corrected – within the period of a few years, but with the creation of the federal reserve we have seen the long and disastrous Great Depression of the 1930s and 40s and just as potentially serious the Great Inflation of the 1970s.

While interest rates may be more constant since the FED came into existence the US economy had been through its most serious disasters.

I question cause and effect.

Interest rates are the price of credit. Wage and price controls always create problems. The control of interest rates creates problems.