The IMF has recently released its Global Financial Stability report. Two figures inspired two questions from me.

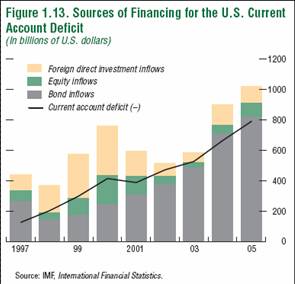

Consider first Figure 1.13:

Figure 1.13 from IMF Global Financial Stability report.

My query is why — if the reason for the United States is the extraordinary trend growth prospects vis a vis other countries — so much of the lending to the US takes the form of debt securities rather than FDI and equity. Could it be that most of the lending is coming from other central banks and quasi-state entities, rather than private actors seeking to obtain the highest return?

Figure 1.14 shows that recent financing of the deficit that is coming in the form debt securities is increasingly in the form of corporate securities.

Figure 1.14 from IMF Global Financial Stability report.

This is somewhat surprising to those accustomed to thinking about central banks and other quasi-state entities, but the IMF report provides some conjecture:

Among the several factors cited as supporting

the growth of fixed-income inflows to the

United States, perhaps the most widely discussed

is the accumulation of official foreign exchange

reserves by foreign central banks, associated

in some cases with efforts to limit appreciation

against the dollar. In addition, the recycling

of petrodollars—often through private sector

intermediaries—has contributed to demand

for U.S. fixed-income instruments. To some

extent, bond purchases by the official sector

may be insulated from market forces. However,

the official sector, like the private sector, has

become more sensitive to implicit interest rate

differentials, in many cases weighing the cost of

issuing domestic debt against the yield earned

on foreign reserves (IMF, 2006b, Annex 1.4). At

the same time, private sector demand for U.S.

fixed-income instruments has also risen.

Increased private sector appetite for these

securities may be attributable at least in part to

global financial integration and—closely associated

with this—a decline in asset home bias. As

will be discussed in Chapter II, a combination of

conditions has worked to ease the flow of capital

across borders. In such circumstances, there

should be an increase in substitutability between

foreign and domestic assets. Accordingly, in

a world of large current account imbalances,

changes in relative interest rates or in other conditions

that might once have had only a muted

impact internationally could lead to sharp

changes in capital flows or exchange rates.

Greater responsiveness to yields on the part

of investors into U.S. bond markets is seen, to

some extent, in the types of fixed-income assets

that they select. Since 2004, a growing share of

purchases by foreigners—including by the offi-

cial sector—has been in agency and corporate

bonds (Figure 1.14). These categories include mortgage-backed securities (MBS) as well as a

host of complex financial products, such as collateralized

debt obligations (CDOs), constructed

from the bonds.

This leads me to a second question. How does the increasing dependence upon bond inflows — even if sourced from the official sector and quasi-state entities — inform our thoughts on how the adjustment to a smaller current account deficit? Some answers come from Freund and Warnock‘s careful examination of 26 current account reversals in developed economies over the 1980-2003 period:

“…Deficits associated with greater bond

inflows do appear to be followed by larger increases in interest rates — perhaps because the bond inflows kept interest rates abnormally low — and a sharper decrease in equity prices.”

Freund and Warnock conjecture that the finding of no impact on the extent of exchange rates and the pace of current account reversals from the many factors examined — including net and gross bond iflows — is due to the following:

“…if the financial system is adept at intermediating, the form of the inflow should not matter; the system will find the best use for the funds, whether they enter the country as direct investment or short-term bond flows.

The evidence we present suggests the latter case. We find no evidence that the

type of financing impacts the outcome for GDP growth or exchange rates. Deficits

associated with larger bond inflows are associated with larger subsequent increases in

short-term interest rates and a greater decrease in equity prices. This is consistent with the

empirical evidence in Sack, Warnock, and Warnock (2005), who show that the cessation

of large bond inflows can lead to a substantial increase in interest rates (which,

presumably, could also lead to a sharper decrease in equity prices).

Now one caveat is that of the 26 episodes examined, only one pertains to the United States; a second caveat is that the past may not be a good guide to the future — although it’s the best we have (macroeconometric models rely on historical data for estimates, and even calibrated models require guesses about underlying parameters based upon historical data). Personally, my view is less sanguine than that presented in the paper, but if the Freund-Warnock results extend to the current US process of adjustment, we should expect the impact to show up in bond and equity markets, with less noticeable effects appearing in GDP and the exchange rate. It will be interesting to see if the increased sensitivity of bond capital flows to interest rates remarked upon in the IMF report further heightens the interest rate effects — especially if the adjustment takes place against a backdrop of financial turmoil in US capital markets (e.g., subprime market collapse).

Technorati Tags: href=”http://www.technorati.com/tags/capital+flows”>capital flows,

current account,

interest rates,

equity prices

For what it is worth, if change in stocks in the survey data (the survey data covers holdings at the end of June and the most recent data point is mid-June 2006) shows:

a) a much smaller increase in foreign holdings of corporate debt than implied by the flow data. I don’t have a good explanation of this. the majority of these flows are “private” – private investors account for $256b of the $292 increase in stocks in the survey, but there isn’t a trend increase in foreign holdings of corp. debt. the TIC flow data — which shows up in the imf chart — shows larger net purchases from mid 05 to mid 06, about $400b.

b) $308b of $320b in the increase in foreign holdings of treasuries/ agencies came from central banks/ official actors. the increase in the flow data is more like $430b, a big discrepancy. the imf data, based on the flow data, shows this — even though it presents annual data not q2-q2 data so it isn’t perfectly comparable.

The fact that official players are behind most agency/ treasury purchases doesn’t surprise me. the big gap between the increase in foreign holdings in the survey and the increase implied by the flows does surprise me –it is now really big. and while the flow data suggests strong growth in demand for US corp debt (including private MBS), the survey data suggests that demand has leveled off.

finally, all the higher frequency variables suggests a big fall off in private demand for us debt/ a big rise in official debt over the past couple of quarters. the increase in the fed’s custodial central bank holdings in q1, annualized, was around $500b. central banks willingness to step up when private flows faltered kept us rates relatively low …

From a Chindia et al perspective the primary difference between shipping their goods to the dump and shipping them to the USA is that the claims that they accumulate can be later used (unless inflated away) to buy parts of the USA.

Can anyone say “Western World Funding Corporation?”

And if Chindia ships its junk here, we have to put it in our dumps.

The local landfill here in San Diego is almost full – wonder how soon it will become economical to mine the damn things?

If central banks and quasi-state entities are investing in US corporate and agency debt, they are going to take it in the shorts just like the pension and hedge funds when long-term rates finally rebalance. To relate to esb’s comment, those claims are going to be worth a lot less than their current market value. China has really gotten itself into a bind here.

Maybe the FCB’s figure the easiest way to acquire America’s corporate assets is via Chapter 11 cram-downs hence the purchase of corporate bonds rather than equities. LOL.

brad setser: Thanks for the insights into what the more current data mean. I think your statement:

should keep us from being too complacent.

esb: I agree that having so much debt outstanding provides a big incentive to renege by inflation or dollar depreciation or both. It is a mystery why foreign purchasers don’t recognize this incentive and demand a higher premium.

“I agree that having so much debt outstanding provides a big incentive to renege by inflation or dollar depreciation or both. It is a mystery why foreign purchasers don’t recognize this incentive and demand a higher premium.”

This mystery is an important one. Asian central banks are lending us money now cheaply to keep their currencies cheap vs. the $–with a virtual certainty that the value of the bonds they purchase will be worth even less as the $ inevitably declines.

Why? 1.Inertia: it has worked well for 3 years. 2.Short-sightedness is not rare amongst economic participants. 3.Fear that allowing Asian currencies to appreciate will expose the unsustainability of the current demand for Asian exports & burst the bubble of over-expansion of export-driven investment.

People need to stop trying to think of this in economic terms and see it for what it is: Business history’s most massive vendor financing fraud. Just as the managements of Nortel and Lucent enjoyed huge bonuses and great acclaim as long as they could lend their customers the money to buy their products, so do the governing elites of Asia enjoy the same sort of benefits. And as with all frauds of this sort, once the fraud has gone on very long, it’s impossible for the fraudsters to stop voluntarily. Any attempt to stop will bring immediate collapse and revelation of the fraud. Although continuing ensures that the final collapse will be even more severe for all the other stakeholders, for the fraudsters it pays to keep it going as long as possible.

Prof. Chinn’s comment that, “…having so much debt outstanding provides a big incentive to renege by inflation or dollar depreciation or both,” misses the point that in fact the currency-manipulating nations incur their losses at the instant they buy dollars at the artificially inflated exchange rates. If you pay 120 yen for a dollar that would only be worth 80 yen in an unmanipulated market, you lost the 40 yen when you bought it; if you continue to pretend it’s worth 120 yen, all you are delaying is the recognition of the loss.

Talk about stability. From a Peruvian-American trying to figure out how to use commodities to better his countries future global instablity will inevitably reach Latin America. It will reach the world. Trust me I feel ya, very worried myself, what is going to manifest 10 years from now?

jm: Vividly expressed. I cannot argue against you. Except to say when a country saves as large a portion of their GDP as China, depresses wage rates legally, & steals a good bit of technology, somebody might manage a free lunch. It will be fascinating to observe.

The assumption that all participants act rationally in economic terms may not be applicable here. The Chinese, obviously knowing the cost of carrying the finance imbalances, are doing it for political reasons, and always with a long-term outlook.

This is my first post and let me start out by saying how impressed I am with the quality of all the comments.

In my humble opinion SE Asian countries esp. China know exactly what they are doing and are doing it from a thoughtful business approach not as a type of must-perpetuate- scam. From it is ‘glorious to be rich’ and the 1991-2 major Chinese currency devaluation, they had a mapped out strategy of exporting their way out of the dark ages bringing 1.5 billion people into the light.

The reality of China is they have developed over the past decade+ the goods exporting platform for the world. If the value of their foreign reserves fall by 10 – xx%, so what, they will still be the goods exporting platform for the world.

China is not in any way, shape or form in any kind of a USD holding / exchange rate bind. The industrialized world has channeled the hard work, poor conditions of factory work to them and they have compressed a 100 year development into 20, simply amazing, this could never had occured pre-1971 Bretton Woods time period.

Think of any future decline in USD reserve holding value as a type of business ‘lost leader’… we get you in the story and lose 20% on item ‘x’ but make it up on everything else…GDP, investment, and jobs.

The MIT and NBER economist R.J. Caballero argues that the current global imbalances, various speculative bubbles, low real interest rates and relatively low inflation are all due to global asset shortages:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=947587

This paper is fairly easy to read and I am curious what any of you think about it. Thanks.