Rising rates look scary, but I still read it as good news.

|

The upward spike in long-term Treasury rates this last month was matched by 30-year mortgage rates, putting us essentially back where we were last summer. Given the lags in the response of home sales to mortgage rates, that will be a factor depressing home sales this fall, mirroring the stimulus I believe we observed last fall. And that depressing effect will come on top of the drag already being exerted by tightening lending standards and inventory of unsold homes.

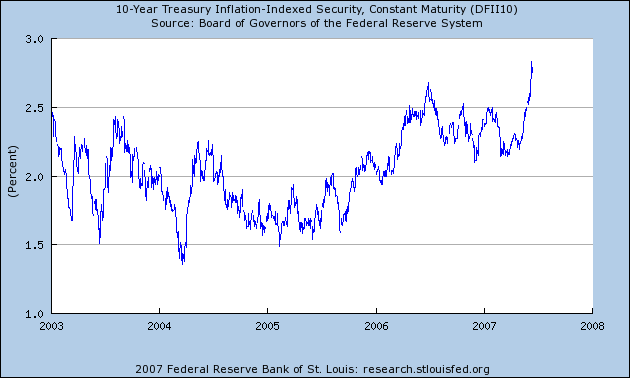

It’s still a little surprising to me that this move seems entirely to be driven by a very rapid rise in long-term real interest rates rather than an increase in expected inflation, but that is the only conclusion one can draw from the yield on inflation-indexed Treasury securities. Recall that both the coupon and principal on these are linked to the headline (not the core) CPI. Whatever investors were responding to, it does not seem to be fears about the future path for the CPI.

|

Could this dramatic rise in real rates be due to a sudden decrease in the willingness of foreigners to buy U.S. debt? Such a shift should also show up in exchange rates. There has been a gradual slide in the dollar this year, but if anything the dollar has strengthened during the period when long rates were rising most dramatically:

|

What about perceptions that the Fed is more hawkish than before? Again it is true that market perceptions this year have gradually been moving away from the notion that the Fed would ease, as reflected for example in the price of the October contract, which has moved from anticipating a cut in the fed funds rate to 5% to a belief that the Fed will hold steady at 5.25%. But again, most of this adjustment in expectations was completed prior to the recent spike in yields.

|

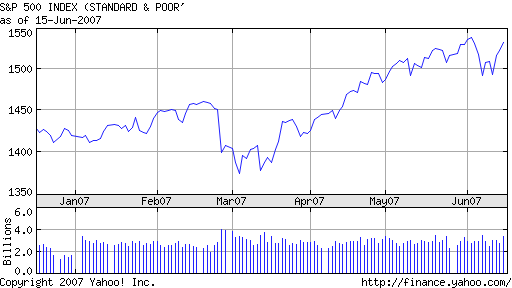

Moreover, if this were purely a rise in real rates induced by either international factors or the Fed, I would have expected to see stock prices fall significantly. If expected future profits and dividends are held constant and the rate at which they are discounted goes up, the stock price would have to fall. Yet we have seen stocks hold their own, even as bond prices plunged, suggesting that rising yields have come at the same time as rising expectations of future profits and dividends.

|

So I want to stick with my story that the biggest factor driving long-term yields must be increasing optimism about the real economic outlook. But I admit that it’s hard to see how housing could be part of that optimistic picture.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

Federal Reserve,

interest rates,

housing

one of best posts on econbrowser ever. really clear exposition of a tough topic. however, as a trader i have seen how fragiel expectations are so…i wouldn’t bet on this financial indicatiors not changing again in the next 6 months.

i am trying to incorporate the st louis fed model in my trading algorithm. thanks.

Interest Rates were due to rise and may be due to “real” inflation rising.

I always suggest looking at the slowness that the ISM captured the inflationary recessions of 1970 and 1974-75 compared to all other downturns since the 60’s? Why is that? Inflation baby. The last 3 months ISM has been overinflated by inflation thus overstating the ISM overhead number.

This also describes the ad hoc inflation of 79-81 inflation that was energy created and Volcker’s blunder. Why the core rate is given such a level of trust by the insiders. But don’t deny overhead inflation, 8-10% isn’t good as seen from the past.

What I think you are seeing is a modest thrust by the other countries to “give back” some of the inflation. Thus boosting treasuries as well. The “official” numbers have not caught it yet, because it lags. But it will. The key is the inflation they are sending back to doesn’t cause a energy shock(Oil doubling in 6 months for example). Though that is usually the sign the inflationary environment is near the end as was 79-82.

dryfly,

Prices paid is not a component of the headline ISM index.

JDH: Do look at the results of the most recent 10-year note auction more closely. If you inspect this series in recent years–say after the 2001 recession–indirect bidders usually get 80% or more of their bids awarded. Indirect bidders, of course, are the category which includes official buyers.

What happened in the auction on Jun 12? Only 34.3% of indirect bids were awarded meaning that, conversely, nearly two-thirds of indirect bidders

put in bids for yields higher than 5.23% (They may have put in some noncompetitive bids, but they rarely do.) Primary dealers, who almost always get a lower percentage of bids awarded, actually got a higher percentage awarded here (39.4%).

It’s just one auction, but should this trend continue, there’d be only one possible explanation–indirect bidders are no longer content with el cheapo rates from Sammy. Hence, rising yields on the long end of the yield curve.

One month data, only, but that’s a dramatic drop in foreigner purchases of long-term U.S. Treasuries:

http://www.treas.gov/tic/tressect.txt

Looks like our buddies the Chinese, sheikhs (who bank in U.K.), and hedge funds (Caribbean banking centers) are selling:

http://www.treas.gov/tic/mfh.txt

This will be ‘fun’ if it continues.

my theory is that there is one other explanation that our host hasn’t considered: a rise in risk premiums.

in other words, maybe inflation expectations haven’t themselves changed yet, but…the fear of inflation expectations changing may well have increased.

Fed Watch: Fed Not Ready to Declare Victory on Inflation

Tim Duy says the Fed is not quite ready to give up its inflationary bias: Fed Not Ready to Declare Victory on Inflation, by Tim Duy: Fed officials like to remind us that inflation remains above their comfort level, but

howard,

a rise in inflation risk premium should show up in the spread between nominal and indexed yields. it has not.

Excellent discussion of recent bond market activity. I too wrestle with these same issues. For sure, there is little near term hope on the housing front…but recently, and oddly, manufacturing activity is showing signs of hope, and this may be a contributing factor to the demise of bonds. Is this for real? Maybe yes, maybe no. One thing is clear, that is the Big-3 have stepped up production, and beefed up scheduled output in from of the expiration of the UAW contract in mid-Sept. The Big-3 are looking for serious wage related concessions, and having some inventory on hand going into the negotiations provides bargaining power. Of course, this inventory building will only borrow strength from the future. It looks to me as if auto prod will add about 0.9% to Q2 GDP and another 0.4% to Q3 GDP. Thereafter, it should be a drag. Thus, what might be scaring the bond market is the uptick in mfg activity, but for the reasons noted above this should be reversed later in the year.

The list of potential causes our host offers for a rise in Treasury note yields is extensive, but I think one important factor is excluded. Once ten-year rates cleared roughly 4.90%, they were in a range not traded since July of last year. Mortgage porfolio hedges were probably mostly appropriate to rates below 4.90%. Once that level was cleared, mortgage portfolios would have been substantial sellers of Treasuries for reasons than have nothing directly to do with growth, inflation or policy expectations. Notice that the rise from 4.90% was far more rapid than the rise prior to that point. I can’t think of why the economic, policy or inflation outlook changed suddenly on June 1, but the trajectory of rates certainly did. It was on May 31 that ten-year yields first cleared 4.90% during the recent rise, and on June 1 that they first settled above that level.

New data should lead to adjustments in expectations of inflation, growth and policy. Let’s see if there are further changes in ten-year rates as sharp as those in the first few days of June. If not, then we might suspect that something, like sudden hedge adjustment, was underway in the first few days of June that does not accompany subsequent adjustments in expectations for policy and fundamentals.

kharris…you make a very good point

matt, my point is a touch subtler: i think after a lengthy period in which the bond market has downplayed risk, it is now reassessing same. for the moment, that means people are demanding a higher real return for their money, not that they are sure that inflation is going up.

But Howard, if the nature of this risk comes from the CPI, you are insured against it with TIPS but not with standard Treasuries. So, if there has been a change in the assessment of this risk, it should have shown up as a change in the relative valuation of these two assets.

jg-

Looks like that series of net foreign purchases of Treasury bonds and notes is pretty volatile in total and even more volatile in the subcategories (official and others). Consequently, it’s a bit of a stretch to run with one month’s data.

Also, “Sammy’s” appetite for new debt is fast approaching zero.

I would also look at the shift of duration of new Treasuries issued. Treasury has been paring back at the short end and issuing significantly more at the long end. I suspect at the old 10 year rate you won’t find many willing takers. Also look at the spread between 6 month T-bill and Fed fund rate.

Ray Stone,

Thank you. From you, I take that as a great compliment.

Professor Hamilton,

thanx for discussion, I came to almost the same conclusions as you when analyzing this. However, I would not view the adjustment in expected effective Fed rate over December-end-of-March period as the revision of market expectation; the trading is very slim there and most of the trading took place from May on. Hence, the previous estimates of Oct. effective rate may not be good approximation of what the “market” expects.