As part of its ongoing efforts at helping the public understand exactly what its intentions might be, the Federal Reserve today released more detailed minutes of its October 30-31 meeting that included the Fed’s expectations for what comes next.

Evidently each governor and reserve bank president was asked to provide his or her projection, however arrived at, for the numbers that they expect to see for GDP growth and inflation over the next three years. Table 1 in today’s release includes the range of numbers that FOMC meeting participants provided. For example, the most pessimistic participant is expecting 1.6% real GDP growth for the four quarters that will end 2008:Q4, while the most optimistic participant is expecting 2.6% growth.

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | |

| GDP | 2.2-2.7 | 1.6-2.6 | 2.0-2.8 | 2.2-2.7 |

| inflation | 2.7-3.2 | 1.7-2.3 | 1.5-2.2 | 1.5-2.0 |

I was particularly struck by the 3-year projections. GDP growth is a time series with relatively rapid mean reversion, so that one would need a lot of evidence (or courage) before offering a 3-year-ahead forecast that is anything other than the historical average. That historical average is 3.3% if you go all the way back to 1948. Yet even the most optimistic FOMC participant was expecting no more than 2.7% real GDP growth for 2010.

Perhaps some would take a view that productivity and GDP growth rates wander persistently (and predictably), and might prefer to base a forecast on the average over just the last five years. Yet the average 4-quarter GDP growth between 2001:Q4 and 2006:Q4 was 2.7%, the upper limit of the FOMC 3-year-ahead projection. These forecasts imply that we’re going to see a 3-year continuation of last year’s unusually sluggish performance, which I would regard as an a priori unlikely scenario. Even if a full-blown and unusually long recession begins in 2008, a recovery should have begun by 2009:Q4 and we will see much better than 2.7% growth for 2010.

| FOMC projection | 1948-2006 average | 2002-2006 average | 2006 actual | |

| GDP | 2.2-2.7 | 3.3 | 2.7 | 2.6 |

| inflation | 1.5-2.0 | 3.3 | 2.2 | 1.9 |

The Fed’s 3-year-ahead inflation forecast also surprises me a little, in that the highest inflation rate that any member anticipates for 2010 is only 2.0%. Inflation is a time series with far less mean reversion than GDP growth, so it’s probably unreasonable to use the long-run historical average inflation rate (3.3%) as your forecast for 2010. But for the FOMC participants unanimously to expect the inflation rate in 2010 to be below its average value of the last five years, and for that matter likely below even its value for 2006, should raise an eyebrow.

So how should we interpret these numbers? The FOMC minutes explain:

Each participant’s projections are based on his or her assessment of appropriate monetary policy.

In other words, the FOMC is saying that, if the Fed (i.e., they themselves) does what they think it should, GDP is going to be growing more slowly and inflation is going to be lower three years from now than a forecast that did not condition on the assumption of such Fed behavior would have anticipated. I believe the spirit of this exercise is to communicate to us that if GDP is growing at 3% in 2010 but inflation is not under 2%, they intend to raise interest rates to bring both down.

For comparison, the 10-year expected CPI inflation implicit in the nominal-TIPS yield spread is over 2.3%. Taken at face value, the Fed is trying to warn us that it intends to be tougher on inflation than markets currently are betting on, and, as I commented last week, the market at the moment appears if anything to be surprisingly confident in the Fed’s ability and commitment to keep inflation low.

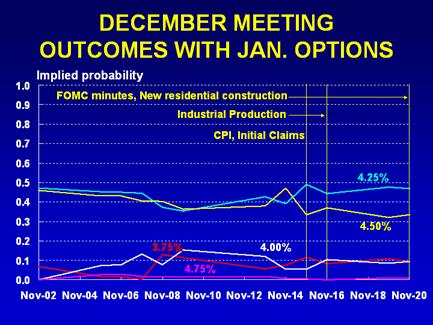

Now, that raises the question– If at some point in the future the Fed is going to surprise the market with a more hawkish policy than is currently anticipated, when will that surprise come? One obvious answer— at the coming December 11 FOMC meeting, for which fed funds options and futures presently seem to be betting pretty heavily on seeing another cut in the fed funds target. If the Fed means what it says with these just-released minutes, the market is wrong to assume that the fed funds target will be lowered to 4.25% on December 11.

|

My reading of these FOMC forecasts appears not to be the common reaction of other analysts, based for example on the failure of today’s fed funds futures prices to re-evaluate the prospects for a December 11 rate cut, and based on the views surveyed at the WSJ, MarketWatch, or Bloomberg. I guess that other people are assuming that the Fed is offering an intentionally pessimistic 3-year forecast for output and intentionally optimistic 3-year forecast for inflation in order to “warn” markets that it’s eventually going to get serious about this inflation thing. Such a scenario reminds me a bit of the mothers I sometimes see in the grocery store with completely wild children whom the mother is constantly admonishing, and thereby accomplishing little more than teaching the child that passionate admonitions from mother mean nothing.

I’m reminded again also of the wisdom of outgoing Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis President Bill Poole:

The best way to establish credibility is to say what you’re going to do, and then do it.

Technorati Tags: macroeconomics,

inflation,

fed funds,

Federal Reserve,

economics

I dunno, Professor. Seems to me — maybe I just hear what I want to hear — that Bernanke and company were talking tough about inflation this summer and fall, and then quickly cut rates at the first whiff of trouble.

I hear Krozner’s comments, but I do not believe him, based on what I saw this summer and fall, and Governor King’s words and actions in England. I see a whole series of cuts coming to combat the trickle, soon to be flood, of bad economic and financial news.

Me, I’m a ‘Poole parent’: I tell my kids once, then I spank. Bernanke should become a ‘Poole parent’ with interest rates.

I had somewhat the opposite reaction to the inflation projections: I saw the Fed as backpedaling on its perceived target. For the last 7 years, we’ve been hearing that the Fed’s “comfort range” was 1% to 2% on the PCE deflator, which led me to assume that the target was 1.5%. If we can take their 3-year forecast as a target, it implies that the actual target is more like 1.75%, and presumably anything below 1.5% would be considered too low (or at least, unnecessarily low).

When comparing the PCE deflator to the CPI, my rule of thumb has been to subtract 0.5% from the CPI. I’m not sure that’s a good rule, but there is certainly a difference: CPI inflation tends to be higher than PCE inflation. By my rule of thumb, the TIPS would be right in sync with the Fed. And I’m inclined to allow at least a few basis points as a net inflation risk premium (the premium for inflation uncertainty in nominal bonds, net of the liquidity premium in TIPS).

Regarding the growth projections, though, I was also pretty shocked by how low they are. Those are the kind of estimates people use when they’re deliberately trying to be conservative. Perhaps that’s what the Fed is doing, trying to lower expectations, so they can congratulate themselves when growth comes in higher, and give themselves political cover in case they decide it’s necessary to tighten despite mediocre growth.

On the other hand, the unemployment projections seemed a tad on the low side compared to the conservative estimates I would have expected from the Fed. (I mean, unemployment is where they really need the political cover, isn’t it?) The unemployment forecasts seem to imply that the NAIRU is about 4.8% (possibly even slightly lower, since they have core inflation declining slightly between 2009 and 2010). That’s pretty much consistent with the consensus, I think, but I would have expected the Fed to be more hawkish by guessing a higher NAIRU.

“I was particularly struck by the 3-year projections. GDP growth is a time series with relatively rapid mean reversion, so that one would need a lot of evidence (or courage) before offering a 3-year-ahead forecast that is anything other than the historical average. That historical average is 3.3% if you go all the way back to 1948.”

Why not go all the way back to 1948 BC? Then the average would be 0.0.

Wow, professor that is one of the best analyses of today’s “new” FED intent that I have read yet. I think you are dead on when you say that the best thing to do is stick to what you say and then do it. I believe Bernanke knows better than to follow the path of lower interest rates, but does he have the ability to stem the tides of political backlash. At the forefront, one would sound a resounding yes as they are suppose to be “free” in terms of decision making ability. I also agree with the market places firm bets on a 25 bp cut at the next meeting is not 80% but rather much lower. The fact that the dollar keeps getting drilled will only continue if the FED keeps on the path of lower rates. He is in a heavy predicament as the stock market is ready for a complete collapse due to sour perceptions around the globe upon the value of U.S. assets. A fiat money system will eventually be put to test to find the true value of its worth and right now the dollar is collapsing and domestically the only thing we can do to stem that tide is to keep rates where they are, let the imbalances work themselves out, not risking a recession, but risking the inevitability of a full out depression. It is the road that is less taken, but one that Bernanke should follow, dropping rates to zero did not help Japan and will not help us. The Ponzi scheme of creating wealth out of nothing will be torn to shreds by increased inflation. Inflation is much higher than the governments numbers lead everyone to believe and if we do not act now, it only makes the situation worse. The lower the rates go the continued false sense of security all of these Wall St. fat cats and palm pressers remains and their new derivative investment vehicles that they use to mitigate so called risk will be back in vogue and sold to willing buyers. They make the commissions, get big bonuses and by the time the trades go bad or they uncover that they are worthless, they will have already been paid! We, the everyday unknowing citizen, takes the brunt of the aftermath by watching our hard earned savings get depleted by inflation and a currency that will continue to be dismantled. Your view in this post is dead on and I suggest you send it to the FED so they can quit sticking their feet in their mouths and give this problem the right solution, throw the dollar the life preserver and cut the fat now! great analysis, I will save and present it to my employees for mandatory reading…..magne13

As our friend Mish says, why not just get rid of the Fed? The proposition that a group of bankers (or economists) somehow know better than the market what ANY interest rate (or unemployment for that matter) is supposed to be is pretty much as anti-free market as you get. Come to think of it, most government programs seem to have outcomes contrary to intent. Fanny May and Freddie Mac come to mind – does anyone think that home ownereship has become more affordable due to their fine stewarship of mortgages?

Very thoughtful perspective.

I was surprised, though I shouldn’t have been, that none of the forecasters was predicting a recession. Which is where I come out, though I don’t think the odds are much higher than 70% at the moment.

One supposed “insider’s” perspective getting some play recently is that this Fed is determined to separate the long-term economic management function of the Fed (balancing growth against inflation) from the burst of liquidity in times of crisis function. So the idea would be that between meetings the Fed might do a major short-term repo program but would not cut the FF rates under any but the most dire circumstances outside of the normal meeting schedule. Trying to kill the “greenspan put” and also fighing the last war, I fear.

Btw, one smart fellow told me to go back and count the requests of the Regional Fed President’s (RFP’s) for discount rate reductions, so I did: the initial Aug 17th 50 bp discount rate cut was immediately requested by 9 of 12 regional Fed banks, the Sept 18th 50 bp discount rate reduction was requested by 7/12 regional fed banks, and the Oct 31st discount rate reduction was requested by only 6/12.

What this suggests is a significant split within the Fed between the inflation hawks and the doves. Bernanke may be caught in the middle, or he may be with the hawks. We’ll see.

Btw, I think it’s time for the professor to update his “inflation expectations” chart — we reran our graph earlier this week and were surprised at how much the TIPS spread had jumped since the first Fed move in mid-August. On our numbers, the TIPS spread is right back up at the annual high for ’07, and the trend is a bit frightening.

The real GDP growth trend is also affected by employment growth, which going forward is likely to be lower than its average over the last 60 years. Obviously, population growth is lower now than it was on average since 1948. Also, Fed economists have argued that labor force participation is likely to decline due to the aging of the baby boomers. See

“The Recent Decline in the Labor Force Participation Rate and Its Implications for Potential Labor Supply,” by Stephanie Aaronson, Bruce Fallick, Andrew Figura, Jonathan Pingle, and William Wascher in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2006:1.

The interesting thing to me was the charts (starting on pg 14, I think) showing how the GDP forecasts had changed from the June meeting (black dashed histogram lines) to the September meeting. While I didn’t see that the longer-term forecasts were revised downward, the year-ahead growth guesses were substantially below and more disperse than what the committee had been thinking a few week earlier. Could it be that the long-term numbers are essentially next year’s number carried out without much adjustment? Sort of an adaptive expectations, random walk process…

Very nice analysis, Professor.

But, echo lowsmoke, one piece that does not fit is the unemployment rate — which is expected to stay around most people’s estimates of natural rate, thus suggests that the FOMC GDP forecasts for 2009 and 2010 could be what they see as the potential.

FYI, under the thread “The challenge of depletion” I posted an analysis of the financial and monetary impact of the oil market’s current situation and 2008 prospects. IMV this factor bears significantly on the potential outcome of different hypotethical Fed’s policy paths.

As you people discuss “how many angels can one fit on the head of a pin”, you totally ignore a the growing world liquidity crisis. Maybe the Fed figures inflation #s will be down, because the country will be in the worst recession (don’t want to say the “d” word) since 1933.

Now it’s a crisis with lying security rating companies, CDOs, SIVs and SIV-lites. Soon it will be crunch time for CLOs and all other ABCP. We live in the time of ‘smoke and mirrors’ derivatives and financial engineers that drive our synthetic economy. Look for the collapse of easy money. In the not to distant future, only the ultra-rich will be able to borrow, but consumers, being mimetic, will have already stopped buying everything else, much in the way they have already stopped buying houses. The future unemployment picture painted by the Fed is probably quite rosey.

Charles Wilson was right when he said, “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country, and vice versa”. If GM hadn’t dumped GMAC, it would probably be bankrupt. One only has to look at the future of the auto companies that are still called “the big three” to figure out the future of the US economy. Ford Motors stock price is now 4.70 eruos. Detroit and Cleveland are the canaries in the coal mine.

I find myself browsing the Fed statement, taking it with a grain of salt. The Fed has abrogated their resposibility so badly in the area of banking regulation, monetary growth, and interest rate policy over the past 10 years, I don’t believe a word they say. The are reactive not proactive.

The bubble economy was obvious three years ago and the Fed should have acted to regulate the credit markets, their only real power. I am sympathetic, but skeptical, to the argument that the Fed was concerned about deflation in the US economy in 2001. They were either stupidly negligent or political in stimulating a credit bubble in conjunction with the economic vacuum created by the corpoarte agenda to off-shore American production. Now that inflation expectations are becoming un-anchored, the dis-incentive to save has swithched from low returns to inflationary destruction or collapse of the financial system.

When will they talk and act to curb speculation ? The incompetence or, perhaps, powerlessness of the Federal Reserve board is reflected in the silliness of their GDP predictions. It feels to me like the small boy whistling past the graveyard.

Thank you for your analysis.

Hi Dr. Hamilton:

I hope all is well. Nice note. I think that the Fed’s new approach to articulating monetary Policy to the market is flawed and less transparent than Greenspan’s old approach of an implicit core inflation target of about 2.5 percent. More is less in Bernanke’s case. He really wanted to implement the inflation targeting approach to monetary policy like we have in Canada and elsewhere and I can say that that approach simply anchors expectations within a very tight band. I do think that in time research will show that inflation targeting is less than optimal. With the Fed now supplying double its past forecasts they will simply confuse the market with more noise and therefore result in less transparency.

Any forecaster knows that a 12-month forecast, let along a 3-year forecast, is a difficult challenge and from what the Fed put out, I would suspect that the likelihood of the Fed getting its target bands met for growth and inflation are very low.

Accordingly, I miss the ‘flexibility’ of Greenspan’s approach where the Fed could change expectations immediately with an unexpected rate cut and stimulate consumer confidence and provide more hope to the consumer about their future outlook for employment and also the impact on financial markets.

Fed Chair Bernanke is a very intelligent man, however, I see his new approach to managing monetary policy as resulting in very static behavior for both consumers and investors.

3 thoughts

A. GDP growth in 2010 FOMC: 2.5% last 5 years 2.7% the FOMC may believe that the last five years average is higher than permanent for 2 reasons: 1)slowing trend labor force growth owing to aging of population. 2) They do not expect any further decline in the unemployment rate as happened over 2001-2006. Why slower than post-WWII average slower labor force growth. QED.

B. PCE inflation 2001 FOMC: 1.75. This is lower than last five years because no more oil shocks (see futures prices). This is lower than TIPS compensation because TIPS includes compensation for inflation risk and is based on CPI which runs higher than PCE.

C. the target for inflation across FOMC is 1.75 above the 1.5 middle of the “comfort zone”. I think here there are two factors. 1) we are currently above the mid-point and the unemployment rate is near the NAIRU. 2) Many members of hte FOMC appear to think that there is no reason to actively try to get below 2% by driving the unemployment rate above the NAIRU. I think they have a loss function that is perfectly happy with any number between 1 and 2 and thus is not characterized by some quadratic term centered on 1.5%.