One of the AEA sessions I attended (at least in part — I missed the first paper) was titled (excitingly) “Reconciliation of Seemingly Inconsistent Data Series”.

In particular, I found Larry Meyer’s talk, entitled “Macroeconomic Advisers–The CPI vs. the PCE Price Index: The Recent BEA-BLS Reconciliation–Some Lessons for the Federal Reserve and Other Policy Makers” very useful for somebody who hasn’t thought long and deeply about what price measure to target. (This is also a nice follow-up to Jim’s last post.)

Unfortunately, his paper is not online anywhere, so I’ll have to recount the important points (or at least the ones I found important) from my notes, and relying on other material on the web.

For me, the most useful aspect of his talk was to remind me that the two measures that people refer to when thinking about monetary policy — the CPI and Personal Consumption Expenditure deflator (or their core counterparts) — are quite different. Figures 1 and 2 below plot the inflation rates according to the CPI and PCE, and core CPI and core PCE, respectively.

Figure 1: Inflation measured by CPI-urban (blue) and PCE (red), as calculated using 12 month change in log level. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Sources: St. Louis Fed FRED II, and NBER, and author’s calculations.

Figure 2: Inflation measured by Core CPI (blue) and Core PCE (red), as calculated using 12 month change in log level. NBER defined recession dates shaded gray. Sources: St. Louis Fed FRED II, and NBER, and author’s calculations.

In my intermediate macro class, I typically observe that the CPI is a Laspeyres price index, while national income and product accounts-based indices such as the PCE are chain-weighted. There’s a well known result that, holding all else constant, Laspeyres price indices overstate inflation, while Paasche understate (loosely speaking). Chain weighted indices, or Fisher Ideal indices, provide a measure that should have the characteristics of an ideal cost of living index (see more nontechnical discussion here. But in some sense, for policy purposes, the big differences arise with respect to the following separate, but related, aspects:

- Weights.

- Revisions.

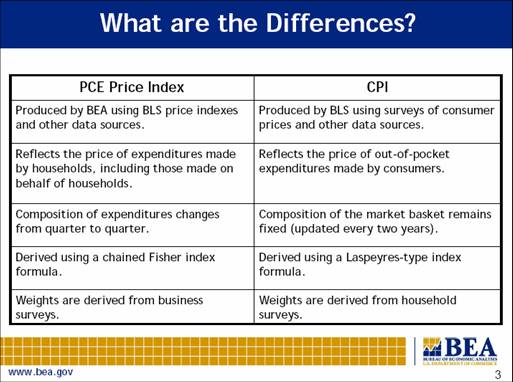

While the Meyer paper is not online, this 2006 presentation by BEA’s Brian Moyer provides an excellent overview of the different attributes of the two series. I reproduce a summary table below.

Figure 3: slide from Moyer (2006).

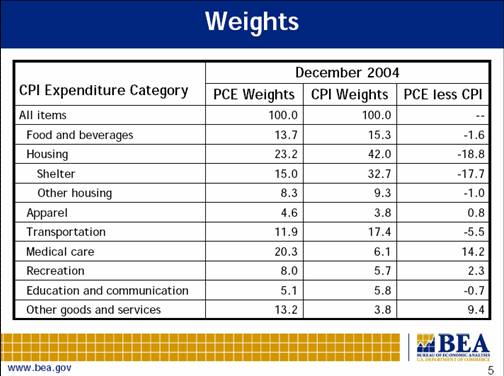

Turning to the first point, note the weights differ substantially; health care accounts for a much larger share in the PCE. Again from the Moyer presentation.

Figure 4: slide from Moyer (2006).

The second point, relating to revisions, means that things can look quite good according to the PCE and PCE-core — until a revision comes along; then things may look quite different. In contrast, the CPI is not revised.

Late addition: To illustrate this point regarding the 2005 NIPA revisions, see this graph from Fernald and Wang (2006) (by the way, this is an excellent review of the same issues — well worth reading!):

Figure 1 from Fernald and Wang, “Shifting Data: A Challenge for Monetary Policymakers” (2006).

Revisions can be substantial exactly because some component of the PCE deflator involves imputing costs, since the transactions are not mediated by the market. Key among these are those in the medical care category (remember, in the PCE, these are not the prices used are not those faced by consumers, but costs of the producers).

The market based PCE mimics the movements of the CPI (a point illustrated in the Moyer presentation), and so it might be a plausible measure to use for monetary policy targetting purposes, although another plausible candidate would be a trimmed mean.

Brookings’ George Perry presented a paper entitled “Conflicting measures of hourly labor costs”; that too is not online. However, the quick summary is as follows. Given the choice between the ECI and the NIPA measures of labor compensation, use the former if one’s concern is with inflationary pressures coming from labor costs. In the case of both measures, better accounting for income derived from exercising options would be welcome.

Technorati Tags: American Economic Association,

Allied Social Sciences Association,

inflation, CPI,

personal consumption expenditure deflator.

What strikes me in the Moyer presentation is the difference in the weighting of housing and health

care.

But it would seem the bottom line for a policy point of view is that it would not really make much difference which one you target, you just have to make a modest difference in your target.

My impression has been that the ECI is designed to capture the cost of keeping the same individual in the same job while the compensation data can be strongly influenced by the changing composition of the labor force or difference in the payment to different parts of the labor force like CEOs.

Is this impression correct?

spencer: I’ve added a figure from Fernald and Wang, which illustrates the fact that revisions can be big (although the 2005 revision is an outlier, and hence more dramatic than the rest). So just applying an adhoc adjustment of say 0.4 ppts on average to match the CPI measure may not be sufficient to account for the divergence between the two series over time.

Regarding your second point, the answer is yes. In the discussion of the Perry paper, there was some mystification why the ECEC, a non-official series with changing weights, exhibited such wide variation versus the ECI (the ECI has fixed weights). No clear answer came out, as far as I could tell.

In another ASSA session, Dean Croushore presented an interesting analysis of the revisions in PCE and PCE-core deflators, with a discussion of the problems this poses for policymakers.

You can find the paper on his web page, or download it at

http://oncampus.richmond.edu/~dcrousho/docs/Croushore_PCEpi_revisions_07Nov.pdf